Charleston’s First Ice Age: Importing Frozen Water

Processing Request

Processing Request

Fire has helped humanity to weather the chill of winter for millennia, but the notion of cooling the summer months is a much more recent phenomenon. In twenty-first century Charleston, it’s easy to take things like refrigeration and air conditioning for granted, but have you ever wondered how and when such technological and cultural changes came to South Carolina? The unnatural notion of sustaining winter into summer began with the idea of preserving ice in hot climates. Our story begins in the 1790s, during an era that I like to call Charleston’s first “ice age.”

Many centuries ago, people living in cool, northern climates learned that winter ice could survive into the summer months if kept in a sufficiently cool environment, such as in a specially-constructed “ice house.” An English ice house of the seventeenth-century, for example, was typically a well-shaded brick structure with thick walls, recessed into the earth to take advantage of the naturally-low soil temperature below the surface. By cutting blocks of ice from nearby frozen ponds and nesting them in deep beds of insulating straw within an ice house, people could keep their butter and wine cool well into the summer months. Temperatures within an ice house could be sufficiently cool to extend the shelf-life of milk and meat, but the structure wasn’t really intended for long-term storage. Nor was it practical for large scale refrigeration. In short, the domestic ice house helped individual families make the most of their food resources through the changing seasons of the year.

The European people who settled in the northern colonies of North America brought with them the traditional technology associated with ice houses. In New England, the ice house made a certain amount of sense. People cut blocks of ice from nearby ponds during the winter and buried them in a straw-filled ice houses during the spring and summer. Some folks in early Virginia built ice houses, too, but the Tidewater climate didn’t always provide sufficient ice to fill them. Here in South Carolina, the climate was definitely too warm to inspire the construction of traditional ice houses. Food spoilage in warm weather was a lamentable fact of life in subtropical Charleston, not to mention in Barbados, Jamaica, and every other tropical location. We coveted the ice houses of our northern neighbors, but ice was simply an unobtainable commodity in the Lowcountry. No one was sufficiently daft to believe that ice could be successfully transported from the frigid North to the sunny South. That is, until people started to try it in the 1790s.[1]

The European people who settled in the northern colonies of North America brought with them the traditional technology associated with ice houses. In New England, the ice house made a certain amount of sense. People cut blocks of ice from nearby ponds during the winter and buried them in a straw-filled ice houses during the spring and summer. Some folks in early Virginia built ice houses, too, but the Tidewater climate didn’t always provide sufficient ice to fill them. Here in South Carolina, the climate was definitely too warm to inspire the construction of traditional ice houses. Food spoilage in warm weather was a lamentable fact of life in subtropical Charleston, not to mention in Barbados, Jamaica, and every other tropical location. We coveted the ice houses of our northern neighbors, but ice was simply an unobtainable commodity in the Lowcountry. No one was sufficiently daft to believe that ice could be successfully transported from the frigid North to the sunny South. That is, until people started to try it in the 1790s.[1]

In late 1797, a Northerner named Jeremiah Jessop built an ice house at a place called Gadsden’s Green, in the northeastern corner of urban Charleston (under the present-day Gaillard Center). Jessop was in the hotel business, and, being new to Charleston, was keen to stand out from the competition. In late February 1798, the Charleston City Gazette noticed that a sloop had arrived the previous day from New York, carrying “sixty tons of ice, to supply the ice-house lately built at the upper end of this city, by Mr. Jessup [sic].” A few months later, in May 1798, Mr. Jessop began selling a curious product called “ice cream” from a shop on the north side Broad Street, near the corner of Union (now State) Street.[2]

Ice Cream was not a new invention in 1798, of course, but it was certainly new to subtropical Charleston. So novel was this “cooling and nourishing refreshment,” as Jessop described it, that some Charlestonians expressed a fear that consuming cold substances in warm weather might be harmful to the body. “To relieve them of such apprehensions,” wrote Mr. Jessop in early June, “he assures them they [the iced creams] may be taken with safety in the greatest state of perspiration; for it is only the rawness of any cold substance which is injurious; and as the creams are composed wholly of nourishing substances, and those boiled before they are frozen, they are the most pleasant and nourishing refreshment that can be taken in a warm climate.”[3]

Jeremiah Jessop sold ice cream by the bowl at his shop on Broad Street and by the pound for family consumption at home. He also sold raw ice at five pounds for a dollar, “for cooling butter in the morning, or other purposes in the course of the day.” A year later, in the summer of 1799, Jessop was also advertising another novelty in Charleston: iced punch, a chilled mixture of spirituous liquors and fruits. Despite the appeal of such refreshing luxuries, Jessop’s business didn’t survive. He continued to ply his trade in the hospitality industry, but Jessop’s creditors sold the ice house at auction in late 1800. Over the next several years, a series proprietors marketed ice cream to Charleston’s summer residents, advertising flavors such as raspberry, pineapple, vanilla, and orange-flower. When the clouds of war with Great Britain began to dampen the port city’s economy in late 1807, however, the small-scale transportation of ice from New England to Charleston came to an end. The city’s first ice house, located somewhere on Gadsden’s Green, disappeared into obscurity.[4]

Jeremiah Jessop sold ice cream by the bowl at his shop on Broad Street and by the pound for family consumption at home. He also sold raw ice at five pounds for a dollar, “for cooling butter in the morning, or other purposes in the course of the day.” A year later, in the summer of 1799, Jessop was also advertising another novelty in Charleston: iced punch, a chilled mixture of spirituous liquors and fruits. Despite the appeal of such refreshing luxuries, Jessop’s business didn’t survive. He continued to ply his trade in the hospitality industry, but Jessop’s creditors sold the ice house at auction in late 1800. Over the next several years, a series proprietors marketed ice cream to Charleston’s summer residents, advertising flavors such as raspberry, pineapple, vanilla, and orange-flower. When the clouds of war with Great Britain began to dampen the port city’s economy in late 1807, however, the small-scale transportation of ice from New England to Charleston came to an end. The city’s first ice house, located somewhere on Gadsden’s Green, disappeared into obscurity.[4]

Meanwhile, in Massachusetts, a Boston-native named Frederick Tudor was dreaming of a grand business venture to ship large quantities of New England ice to the Caribbean. He was convinced that blocks of ice, cut from frozen ponds in winter, could survive such a long journey aboard wooden ships if they were packed with copious amounts of insulating straw and sawdust. Tudor’s friends and neighbors thought he was mad, but in 1806 he succeeded in transporting a shipload of ice to the Caribbean island of Martinique. Some of the product melted and evaporated before reaching its destination, of course, but the loss was within acceptable limits to prove the viability of the concept. Unfortunately for Mr. Tudor, the advent of a new naval war with Britain in 1807 ruined the prospects of expanding his icy enterprise. Charleston would have to wait a few more years for the dawning of a new ice age.[5]

Shortly after the conclusion of the War of 1812, Frederick Tudor traveled down the Atlantic coastline from Boston to places like Charleston, Savannah, and various Caribbean islands, looking for investors to retail the ice he wanted to ship from Massachusetts. Here in Charleston in 1816, Tudor partnered with Samuel Davenport and his associate, William Lindsay, to construct a wooden facility on Christopher Fitzsimons’s wharf on the Cooper River waterfront (today this site is under the U.S. Customs House building). No details of the building’s construction survive, but evidently it was designed as a temporary structure—a modest investment to test the local market. The building was completed by March of 1817, when its proprietor or manager, Nathaniel Batchelder, advertised that the Charleston “Ice House” would open as soon as their stock of ice arrived from its northern source.[6]

On the fifth day of April, 1817, a brig from Boston sailed into Charleston harbor after a passage of sixteen days, carrying “200 tons [of] ice, for the Ice House lately established in this city.” From that moment in the spring of 1817 until the first shots of the American Civil War in April 1861, Charlestonians enjoyed a continuous supply of Yankee ice to cool our Southern summers. The business was not exactly profitable in the early years, according to contemporary newspaper reports, but it survived because Charleston’s first commercial ice house was essentially a franchise of a larger commercial enterprise under the growing umbrella of the Tudor Ice Company. By fixing their prices low (initially just over eight cents per pound) and providing a steady supply of their product, the company created a market that soon generated perpetual demand. A few other local proprietors tried to pry their way into the ice market as well, but none survived more than a year or two of competition with the Tudor empire of ice.[7]

On the fifth day of April, 1817, a brig from Boston sailed into Charleston harbor after a passage of sixteen days, carrying “200 tons [of] ice, for the Ice House lately established in this city.” From that moment in the spring of 1817 until the first shots of the American Civil War in April 1861, Charlestonians enjoyed a continuous supply of Yankee ice to cool our Southern summers. The business was not exactly profitable in the early years, according to contemporary newspaper reports, but it survived because Charleston’s first commercial ice house was essentially a franchise of a larger commercial enterprise under the growing umbrella of the Tudor Ice Company. By fixing their prices low (initially just over eight cents per pound) and providing a steady supply of their product, the company created a market that soon generated perpetual demand. A few other local proprietors tried to pry their way into the ice market as well, but none survived more than a year or two of competition with the Tudor empire of ice.[7]

The Tudor business flourished in Charleston and in other cities because the company marketed their product in with a four-prong strategy that facilitated a new culture of luxury consumerism. They sold ice to individuals and families for domestic use, of course, and also sold insulated ice chests called “refrigerators” or “little ice houses” for storing ice at home. (Thomas Moore of Maryland, by the way, patented the first “refrigerator” in 1802.) In addition to these household luxuries, the Tudor company also sold bulk ice to restaurants, saloons, and ice-creameries for commercial use in the emerging food-and-beverage industry. Finally, the Boston-based firm sold access to cold storage within their corporate ice houses across the country. Starting in the spring of 1817 in Charleston, you could take ice home for a few pennies per pound, sip an iced beverage at a Market Street saloon, promenade on the newly-built Battery with a cup of ice cream, or chill your expensive beef tenderloin for weeks on end. Restaurants could also send their creams and cakes and chops to the local ice house to prevent waste and spoilage. All of these things we take for granted in the twenty-first century were quite new and quite refreshing in antebellum Charleston.[8]

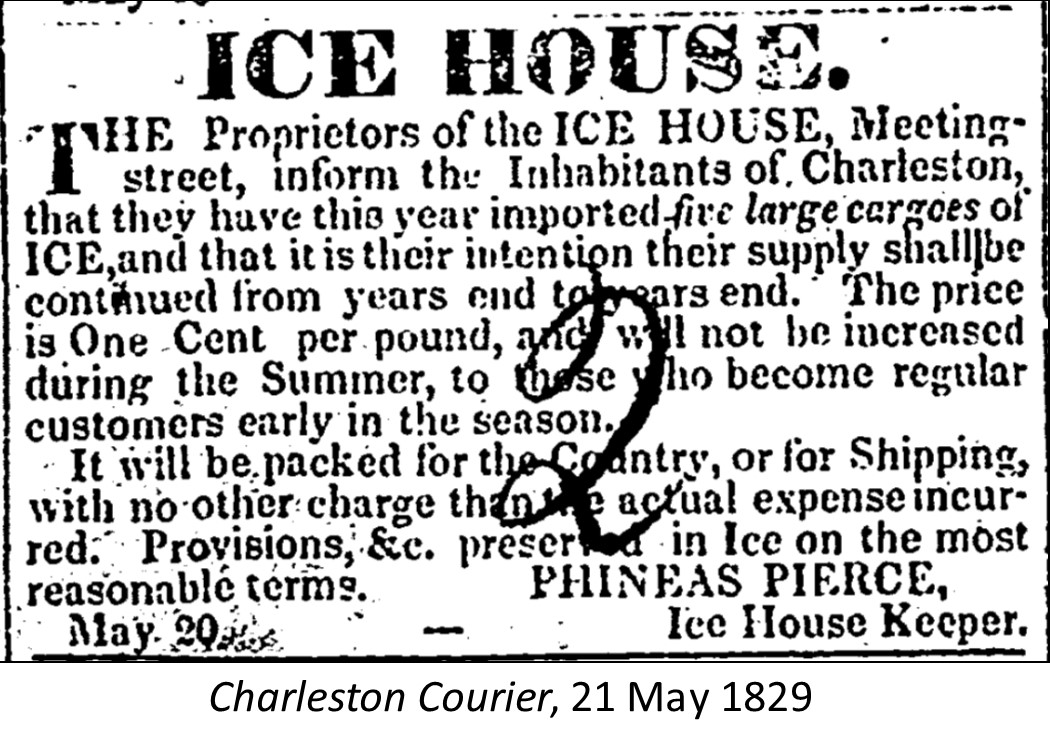

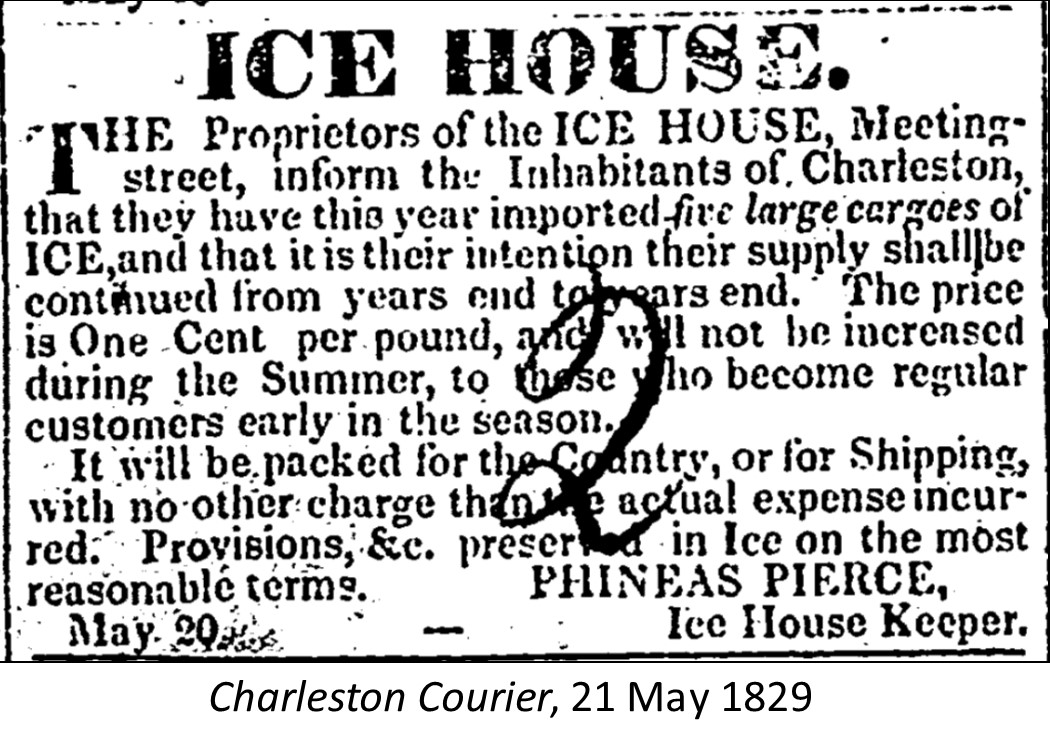

Charleston’s first commercial ice house on Fitzsimons’s Wharf was established by Frederick Tudor and the local firm of Davenport & Company, but those men were just the investors. Nathaniel Batchelder, who styled himself “ice house keeper” in early newspaper advertisements, managed the first Charleston Ice House from its opening in early 1817 through the autumn of 1822. In December of that year, Massachusetts-native Phineas Pierce became the ice master of Charleston and held that post for nearly four decades, up to the beginning of the Civil War.[9]

Charleston’s first commercial ice house on Fitzsimons’s Wharf was established by Frederick Tudor and the local firm of Davenport & Company, but those men were just the investors. Nathaniel Batchelder, who styled himself “ice house keeper” in early newspaper advertisements, managed the first Charleston Ice House from its opening in early 1817 through the autumn of 1822. In December of that year, Massachusetts-native Phineas Pierce became the ice master of Charleston and held that post for nearly four decades, up to the beginning of the Civil War.[9]

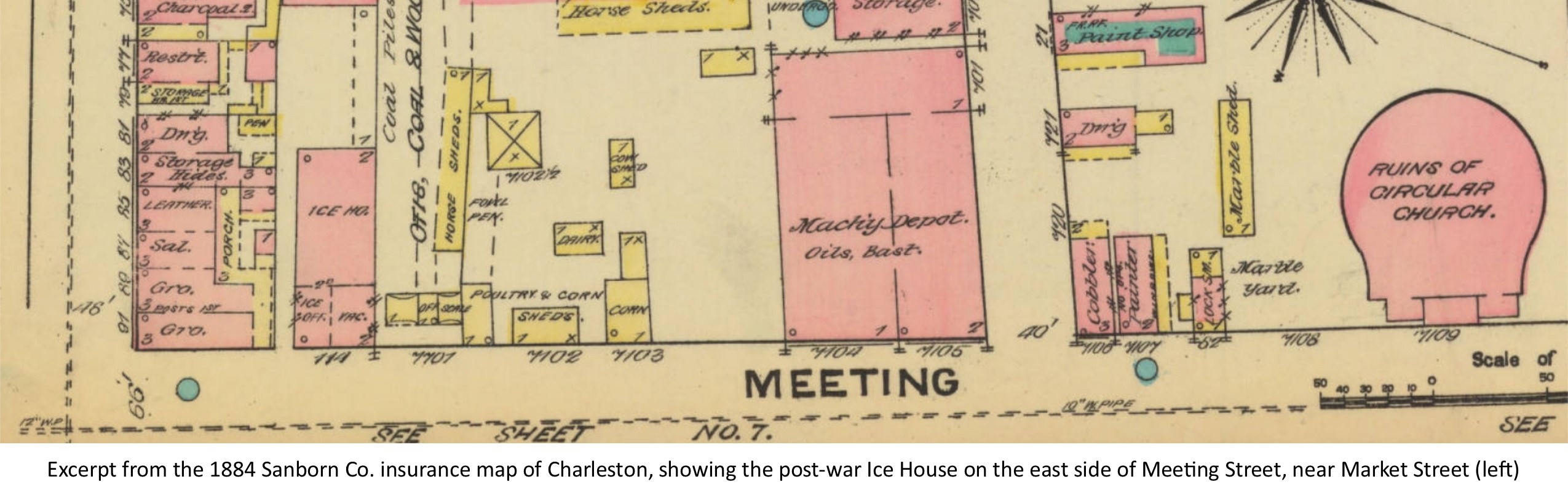

In July of 1827, Phineas Pierce placed a notice in the Charleston newspapers stating that his business partners were looking to purchase a lot of land “on which to erect a large permanent Brick Ice House.” Piece specified that the proposed lot “must be situated somewhere between Broad, Market, East Bay and King streets—a rear lot, if accessible from the front by carts will answer.” A few months later, in November of 1827, Frederick Tudor and his local partners purchased a vacant lot on the east side of Meeting Street, just one door south of Market Street (this site is now called 182 Meeting Street). The lot was fifty feet wide and nearly 270 feet deep, in the center of which the Tudor Ice Company built a large, square, brick structure that cost approximately $15,000. Before Charleston’s new ice house opened to the public in May of 1828, it received the cargo of four large ice ships from Massachusetts, containing a total of more than 1,000 tons of ice. For the next thirty-odd years, this brick vault was the center of Charleston’s ice trade.[10]

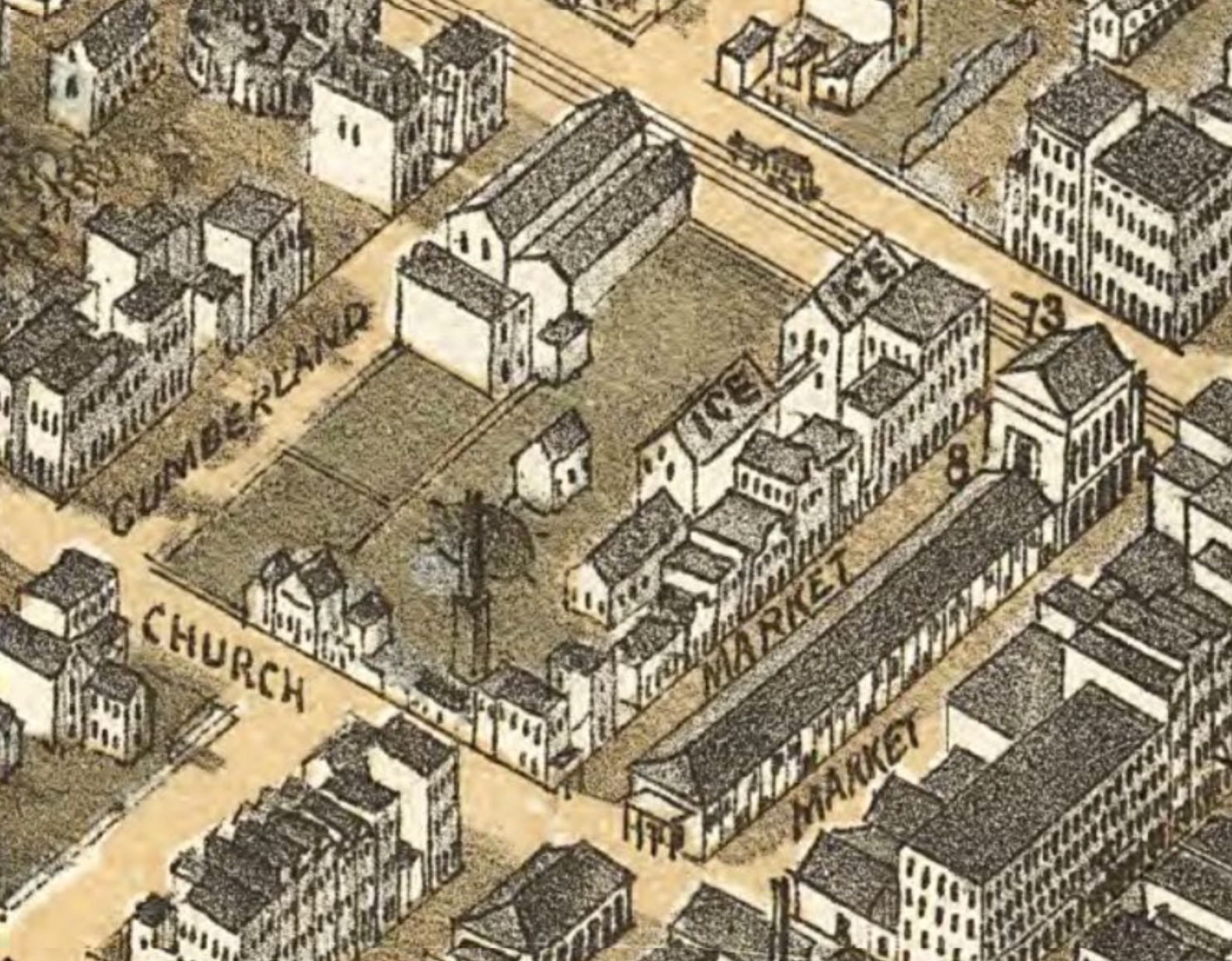

The newspapers of antebellum Charleston are full of details about the ice business and its ancillary activities. In the interest of time, I’ll mention just a few anecdotes to give you an idea of the flavor of the era. In August 1827, the Commercial Coffee House on East Bay Street announced that “in consequence of the high price of ice, punch and all mixed liquors, will resume the old price, 12 ½ cents per glass.” A complaint about market prices in March 1832 tells us that while a joint of meat (like a leg of lamb), might cost between 37 and 50 cents, the price of storing that meat in the Ice House overnight cost six and a quarter cents.[11] On July 2nd, 1836, the City Council of Charleston ratified “An Ordinance to prevent Fish deposited in Ice Houses from being sold in the Market or streets.” Evidently the public wasn’t quite ready for the concept of refrigerated, nearly-fresh fish.[12] A group of local businessmen formed a new ice company in 1840 and the following year opened the “Charleston Ice House” at the northeast corner of Church and North Market Streets.[13] By the late 1840s, there was a small ice house adjacent to the Public Market on Charleston Neck, at the northwest corner of St. Philip and Vanderhorst Streets.[14] Alva Gage (1820–1896), a native of New Hampshire purchased both of the latter establishments in 1853 and 1856 and quickly became the dominant force in the city’s ice business.[15]

The outbreak of the American Civil War in the spring of 1861 brought an end to the regular shipment of Yankee ice into Charleston and other southern cities. In September of that year, the Charleston Ice House announced that their stock of ice was gone. “We expect to continue business,” Alva Gage told customers, “as soon as there is any possibility of securing a supply of ice.” Little did they know that nearly five years would pass before the next opportunity to receive shipments of ice from New England.[16]

While Americans were fighting our Civil War during the early 1860s, scientists in Europe were tinkering with the idea of making artificial ice. The technique of using ammonia to freeze water in warm climates spread across the globe in the 1860s and soon the advent of machine-made ice threatened to surpass the old business of transporting ice by ship. Charleston’s first ice-making machine arrived from New England in 1870, from which time we can date the commencement a new era of ice and refrigeration in our community. The concept of refrigerated air, and then air conditioning, was just around the corner. But that’s a story for a later program (see Episode No. 238).

Charleston’s first “ice age,” 1798 to 1861, was an era in which the importation of natural ice from New England transformed the culture and the flavors of our community. The year-round availability of ice facilitated the emergence and growth of what we now call “the food-and-beverage industry,” a business sector that now caters to millions of customers in the Charleston metro region every year. The next time you’re enjoying an ice cream cone on the Battery, sipping a chilled mint julep at a Market Street saloon, or tucking into a plate of imported seafood on the waterfront, remember the extraordinary efforts that made these luxuries possible, and the novelty of their first appearance. In 1798, Jeremiah Jessop assured Charlestonians that it was safe to eat ice cream while perspiring in June. More than two hundred years later, I think we’re all very comfortable with that practice today.

Charleston’s first “ice age,” 1798 to 1861, was an era in which the importation of natural ice from New England transformed the culture and the flavors of our community. The year-round availability of ice facilitated the emergence and growth of what we now call “the food-and-beverage industry,” a business sector that now caters to millions of customers in the Charleston metro region every year. The next time you’re enjoying an ice cream cone on the Battery, sipping a chilled mint julep at a Market Street saloon, or tucking into a plate of imported seafood on the waterfront, remember the extraordinary efforts that made these luxuries possible, and the novelty of their first appearance. In 1798, Jeremiah Jessop assured Charlestonians that it was safe to eat ice cream while perspiring in June. More than two hundred years later, I think we’re all very comfortable with that practice today.

[1] A few South Carolina plantations, such as Bleak Hall on Edisto Island, are known to have included detached ice houses.

[2] [Charleston, S.C.] City Gazette, 23 February 1798, page 3; City Gazette, 4 May 1798, page 3.

[3] City Gazette, 2 June 1798, page 3.

[4] Ibid; South Carolina State Gazette, 28 February 1799, page 3; and 23 March 1799, page 3; City Gazette, 4 September 1799, page 3; and 30 September 1800, page 3. See Gaston’s advertisement in City Gazette, 14 March 1804, page 2. Vauxhall Garden, at the northeast corner of Broad and Friend Streets, regularly advertised ice cream during the early years of the nineteenth century, and specified flavors in Charleston Courier, 3 July 1806, page 3.

[5] For details of Tudor’s career, see Gavin Weightman, The Frozen Water Trade: A True Story (Westport, Conn.: Hyperion, 2003).

[6] Courier, 8 March 1817, page 3, “Ice-House Establishment.”

[7] City Gazette, 7 April 1817, page 2, “Ship News.” The price of ice is mentioned in Batchelder’s initial advertisement in Courier, 8 March 1817. Phineas Pierce’s “Ice House Notice” in Courier, 2 December 1822, page 2, recounted the poor business of the past several years.

[8] A description of Thomas Moore’s “refrigerator” appears in Carolina Gazette, 7 October 1802, “From the Washington Federalist.” Descriptions of refrigerators and ice decanters appear in Batchelder’s initial advertisement in Courier, 8 March 1817.

[9] Phineas Pierce first advertised in Courier, 2 December 1822, page 2, “Ice House Notice.”

[10] Courier, 14 July 1827, page 3, “Wanted to Purchase”; John Garden and his wife, Elizabeth, to Frederick Tudor, conveyance of a lot on Meeting Street for $4,600, 7 November 1827, Charleston County Register of Deeds Office, book U9: 404–6; Courier, 1 May 1828, page 3, “Meeting-Street Ice House”; Courier, 28 June 1828, “Ice in Charleston.”

[11] Courier, 22 August 1827, page 3; Southern Patriot, 5 March 1832, page 2, “Counter Memorial.”

[12] “An Ordinance to prevent Fish deposited in Ice Houses from being sold in the Market or streets,” ratified on 2 July 1836, in City Council of Charleston, Ordinances of the City of Charleston: from the 5th Feb., 1833, to the 9th May, 1837 (Charleston, S.C.: A. E. Miller, 1837), 82.

[13] Courier, 19 September 1840, page 3, “To the Inhabitants of Charleston”; Courier, 4 May 1841, page 2, “Charleston Ice House.”

[14] An “Ice House” appears on the west side of Charleston’s Upper Market in a plat dated 20 December 1828 in McCrady Plat No. 7859 at the Charleston County Register of Deeds Office.

[15] Charleston Ice Company to Alva Gage, conveyance of property at the corner of Market and Church Streets for $16,000, 29 January 1856, Charleston County Register of Deeds, V13: 70–78; News and Courier, 15 May 1874, page 1: “The Ice Question”; Gage’s business is described, with some inaccuracies, in An Historical and Descriptive Review of the City of Charleston (New York: Empire Publishing Company, 1884), 108.

[16] Courier, 30 September 1861, page 2, “Ice Notice.”

PREVIOUS: Firewood Cures the Winter-Time Blues

NEXT: The End of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments