Remembering Rhettsbury

Processing Request

Processing Request

One of Charleston’s least-remembered eighteenth-century neighborhoods was a suburban plantation known as “The Point,” then “Rhett’s Point” or “Rhettsbury,” and later, “Trott’s Point.” This tract, which encompassed approximately thirty-five acres between King Street and the Cooper River, was assembled in the 1690s by Jonathan Amory, expanded in 1714 by William Rhett, and subdivided in 1773 by the husbands of Rhett’s great-granddaughters. Most people today think of this property as comprising the southernmost part of the neighborhood called Ansonborough, but it has a history and identity of its own that deserves to be remembered.

Jonathan Amory (1654–1699) was an English-born merchant who came to South Carolina in the late 1680s by way of Barbados and Ireland. In the 1690s he became an active public figure here and rapidly acquired money and property. By the time of his death, Amory was speaker of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, Public Treasurer, and Advocate General of the colony.[1] Shortly before his death, Jonathan Amory had assembled a small plantation just a stone’s throw north of the boundary of Charles Town. I know of no record of Amory’s name for this property, but he may have called it “the Point,” as that name seems to have been the common denominator for the easternmost part of this property throughout the eighteenth century. The property included ten acres of land he had purchased from Isaac Mazyck, ten acres purchased from Job Howes, and fourteen numbered, half-acre town lots granted to or purchased by Amory (Nos. 48, 121, 122, 123,138, 139, 208, 209, 234, 235, 302, 303, 304, 305).[2]

Jonathan Amory (1654–1699) was an English-born merchant who came to South Carolina in the late 1680s by way of Barbados and Ireland. In the 1690s he became an active public figure here and rapidly acquired money and property. By the time of his death, Amory was speaker of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, Public Treasurer, and Advocate General of the colony.[1] Shortly before his death, Jonathan Amory had assembled a small plantation just a stone’s throw north of the boundary of Charles Town. I know of no record of Amory’s name for this property, but he may have called it “the Point,” as that name seems to have been the common denominator for the easternmost part of this property throughout the eighteenth century. The property included ten acres of land he had purchased from Isaac Mazyck, ten acres purchased from Job Howes, and fourteen numbered, half-acre town lots granted to or purchased by Amory (Nos. 48, 121, 122, 123,138, 139, 208, 209, 234, 235, 302, 303, 304, 305).[2]

Jonathan Amory died in October 1699, during a yellow fever epidemic that swept through urban Charleston. His wife, Martha, died a few weeks later of the same sickness. In Mrs. Amory’s will, she appointed Sarah Cooke Rhett (1665–1745) to be the guardian of her minor children and the trustee of the extensive real estate they would inherit. Through a series of legal subterfuges in the early years of the eighteenth century, however, Sarah Rhett and her husband, William Rhett (1666–1723), essentially hijacked the bulk of the Amory inheritance and claimed it as their own. Around the year 1712 they built a large country mansion house near the center of the property, the location of which is now called No. 54 Hasell Street. In 1714 the Rhetts expanded this property by obtaining a grant for eight acres of marsh land fronting on the Cooper River (where today one can see a field of BMWs awaiting export).[3]

William and Sarah Rhett called this suburban plantation Rhettsbury, or Rhett’s Point. They held the land as a “joint tenancy,” so the passing of Colonel Rhett in early 1723 left his widow in full possession of the property. In the spring of 1728, Sarah Rhett married retired Chief Justice Nicholas Trott (1663–1740), and for some time after that date you’ll find references to the property as “Trott’s Point.” Prior to their marriage, however, Sarah Rhett and Nicholas Trott settled a pre-nuptial agreement that allowed Sarah to maintain full control over “Rhetts berry” (as she called it her in 1745 will). While still residing at her ca. 1712 mansion, Sarah Rhett Trott elected to devise that property to the future children of her youngest daughter, Mary Rhett (1714–1744).[4]

In the spring of 1734, just before Mary Rhett wed Richard Wright (1698–1745), Mr. and Mrs. Trott placed Mary’s inheritance in a trust administered by the Rev. Alexander Garden and Joseph Wragg. The purpose of the trust was to preserve the Rhettsbury property intact for any children of the Rhett-Wright union. Young Mary Rhett’s husband was essentially to serve as a mere caretaker of the property for the next generation. In the meantime, Sarah Rhett and Nicholas Trott continued to enjoy their peaceful suburban retreat until the old Chief Justice died in 1740. Following his death, it appears that Richard Wright and his wife shared the Rhett mansion with the widow Trott. In the autumn of 1743, for example, Captain Richard Wright notified his fellow members of Charleston’s 2nd Troop of Horse to muster on October 31st, “well mounted and accoutered, by 8 o’clock in the Morning, at Mrs. Trott’s Gate.”[5]

In the spring of 1734, just before Mary Rhett wed Richard Wright (1698–1745), Mr. and Mrs. Trott placed Mary’s inheritance in a trust administered by the Rev. Alexander Garden and Joseph Wragg. The purpose of the trust was to preserve the Rhettsbury property intact for any children of the Rhett-Wright union. Young Mary Rhett’s husband was essentially to serve as a mere caretaker of the property for the next generation. In the meantime, Sarah Rhett and Nicholas Trott continued to enjoy their peaceful suburban retreat until the old Chief Justice died in 1740. Following his death, it appears that Richard Wright and his wife shared the Rhett mansion with the widow Trott. In the autumn of 1743, for example, Captain Richard Wright notified his fellow members of Charleston’s 2nd Troop of Horse to muster on October 31st, “well mounted and accoutered, by 8 o’clock in the Morning, at Mrs. Trott’s Gate.”[5]

During the final years of Mrs. Trott’s life, the only significant change to the property occurred in 1744, when an act of the legislature extended East Bay Street northward from Daniel’s Creek (now Market Street) to the town boundary (just south of modern Hasell Street). That intrusion into Rhettsbury was softened by the fact that a decade earlier, the Trotts had sold off the exact piece of real estate that was impacted by the extension of East Bay Street (in several waterfront lots). It was almost as if they somehow knew that property would eventually give way to the inevitable march of urban sprawl. Perhaps they had insider knowledge. At any rate, in the late 1740s, the southeasternmost part of Trott’s Point, as it became known, developed a life of its own. The area between the north end of East Bay Street and the Cooper River became a haven for shipbuilders and related trades. Today there’s a huge Ports Authority warehouse on this spot, opposite the east end of Guignard Street and Pinckney Street.[6]

The death of Sarah Rhett Trott in 1745 signaled the end of an era of relative stability for Rhettsbury. Although she had created a trust in 1734 to ensure the property would descend to her grandchildren, Sarah actually outlived some of that plan. Her daughter, Mary Rhett Wright, and her husband, Richard Wright, died in 1744 and early 1745, respectively. Their only child, Sarah Wright (1736–1754), was too young to manage her inheritance, so another adult had to step into the picture. Newspaper advertisements from the late 1740s and early 1750s show that Thomas Smith “of Broad Street” (1720–1790), Mrs. Rhett’s grandson-in-law, and Thomas Wright (d. 1766), the uncle of young Sarah Wright, were both actively renting out the old Rhett mansion and the adjacent grounds.[7]

In 1750, sixteen-year-old Sarah Wright married James Hasell Jr. (1727–1769) of North Carolina. Since Sarah and James spent most of their time in North Carolina, evidence suggests they continued to use local agents, like Thomas Smith and Thomas Wright, to manage the leasing of Rhettsbury and other Charleston properties. Between the late 1750s and 1774, for example, it appears that Santee River planter Thomas Lynch Sr. (1727–1776) inhabited the Rhett mansion and kept a number of race horses within the fenced boundaries of Rhettsbury. This conclusion is based on numerous newspaper advertisements for “Lynch’s Pasture,” which name Thomas Lynch as the current leaseholder of that property. In fact, I’m tempted to conclude that the name “Lynch’s Pasture” was used throughout the 1760s and early 1770s to refer to the entirety of Rhettsbury located west of East Bay Street, while the name “Trott’s Point” was used during that same time to identify the old Rhett-Trott property located to the east of East Bay Street.[8]

In 1750, sixteen-year-old Sarah Wright married James Hasell Jr. (1727–1769) of North Carolina. Since Sarah and James spent most of their time in North Carolina, evidence suggests they continued to use local agents, like Thomas Smith and Thomas Wright, to manage the leasing of Rhettsbury and other Charleston properties. Between the late 1750s and 1774, for example, it appears that Santee River planter Thomas Lynch Sr. (1727–1776) inhabited the Rhett mansion and kept a number of race horses within the fenced boundaries of Rhettsbury. This conclusion is based on numerous newspaper advertisements for “Lynch’s Pasture,” which name Thomas Lynch as the current leaseholder of that property. In fact, I’m tempted to conclude that the name “Lynch’s Pasture” was used throughout the 1760s and early 1770s to refer to the entirety of Rhettsbury located west of East Bay Street, while the name “Trott’s Point” was used during that same time to identify the old Rhett-Trott property located to the east of East Bay Street.[8]

During the final years of James Hasell Jr.’s management of Rhettsbury, two other civic changes impacted the peace of this suburban plantation. First, in the summer of 1767, an act of the legislature extended Meeting Street northward from Daniel’s Creek (now Market Street) through Lynch’s Pasture to George Street. Second, another act of the legislature in 1769 moved the town boundary northward to Boundary Street (now Calhoun Street), which transformed Rhettsbury into a sort of anomaly—an urban plantation.[9]

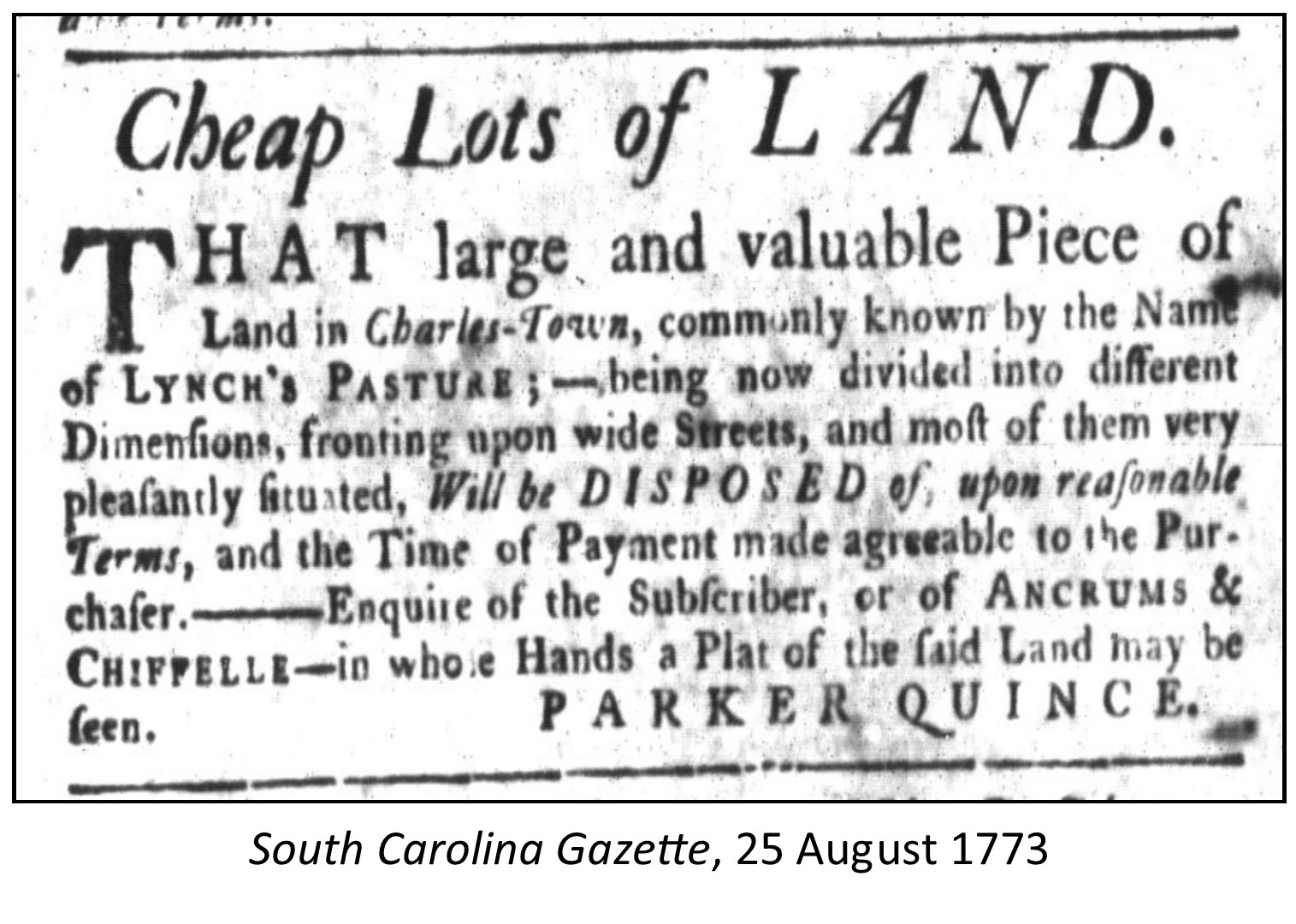

Following the death of James Hasell Jr. in 1769, the property traditionally known as Rhettsbury, but more recently styled Lynch’s Pasture, descended to his two daughters (the great-granddaughters of William and Sarah Rhett): Susannah Hasell (1752–1812), who in 1767 married Parker Quince (1743–1785), and Mary Hasell (1753–1794), who in 1768 married John Ancrum (d. 1779). Since both of these families were permanent residents of North Carolina, however, they had no personal attachment to this Charleston property. They assigned power of attorney to locals to manage the land and collect rents, but the lifespan of Rhettsbury plantation was drawing to an end.[10]

The population and the built environment of Charleston expanded rapidly in the decade preceding the American Revolution, and so market forces might have triggered the owners of Rhettsbury to subdivide the property. The plantation immediately north of Rhettsbury, once called the Bowling Green, had been subdivided and marketed as Ansonborough since 1745 (see Episode No. 111). In the spring of 1770, the Harleston family began marketing the subdivision their large green space immediately west of Rhettsbury and Ansonborough (see Episode No. 136). At the same time, the Pinckney family had been selling off parts of Colleton Square, just south of Rhettsbury, since 1743.

The population and the built environment of Charleston expanded rapidly in the decade preceding the American Revolution, and so market forces might have triggered the owners of Rhettsbury to subdivide the property. The plantation immediately north of Rhettsbury, once called the Bowling Green, had been subdivided and marketed as Ansonborough since 1745 (see Episode No. 111). In the spring of 1770, the Harleston family began marketing the subdivision their large green space immediately west of Rhettsbury and Ansonborough (see Episode No. 136). At the same time, the Pinckney family had been selling off parts of Colleton Square, just south of Rhettsbury, since 1743.

In the autumn of 1773, the Quince and Ancrum families of North Carolina executed a deed of partition that subdivided Rhettsbury into lots to be divided between the two great-granddaughters of William Rhett. They hired Charleston surveyor and architect Rigby Naylor to create a plat of Rhettsbury that divided the land into nineteen large, numbered lots, each labeled either “A” for Susannah Hasell Quince or “B” for Mary Hasell Ancrum. Each of these lots was later subdivided into a number of smaller building lots before being advertised for sale. In addition to these lots, Naylor’s 1773 plat includes several new streets to be cut through the property, named Hasell Street, Trott Street, Quince Street, Ancrum Street, and Maiden Street (now Maiden Lane). With the exception of Hasell Street and Maiden Lane, the rest of these 1773 street names did not survive for long. The City of Charleston passed an ordinance on 31 January 1806 that merged Trott Street with Wentworth Street (a street created in Harleston in 1770), Quince street with Anson Street (created in 1745), and Ancrum Street with Pinckney Street.[11]

Beginning in late 1773 and continuing for more than a decade, you can find numerous newspaper advertisements for the sale of lots in this new subdivision that lacked a name. If you search through the old Charleston newspapers looking for post-1773 references to Rhettsbury or Rhett’s Point, you’ll be disappointed. Most of the advertisements I’ve seen for this property simply mention the sale of building lots fronting on newly-created streets. When they do mention a place name to help you locate to site, it’s usually called Lynch’s Pasture. In the years following the American Revolution, it seems, the names Rhett, Trott, and Lynch quickly faded from Charleston’s collective memory.[12]

In the early nineteenth century, as Charleston’s new Centre Market in Market Street grew into a vibrant institution, all of the land between the market and Boundary (Calhoun) Street, east of King Street, became homogenized under the denomination of Ansonborough. Consider, if you will, the great Ansonborough fire of April 1838, which burned a large swath of land from East Bay to King Street, just north of the market.[13] Nearly all of the real estate consumed in that terrible conflagration was actually once the property of Jonathan Amory, who trusted the Rhetts to protect it for his heirs. Three centuries after the demise of Mr. Amory and Colonel Rhett, and all of their heirs, few who live in this neighborhood today remember the legacy of “The Point,” or Rhettsbury. The next time you’re strolling down Hasell Street, I recommend pausing in front of the old Rhett mansion at No. 54 to reimagine the scene. Though crowded and bustling today, that site was once a sort of genteel oasis lodged in a picturesque garden facing the morning sun rising over the Cooper River.

In the early nineteenth century, as Charleston’s new Centre Market in Market Street grew into a vibrant institution, all of the land between the market and Boundary (Calhoun) Street, east of King Street, became homogenized under the denomination of Ansonborough. Consider, if you will, the great Ansonborough fire of April 1838, which burned a large swath of land from East Bay to King Street, just north of the market.[13] Nearly all of the real estate consumed in that terrible conflagration was actually once the property of Jonathan Amory, who trusted the Rhetts to protect it for his heirs. Three centuries after the demise of Mr. Amory and Colonel Rhett, and all of their heirs, few who live in this neighborhood today remember the legacy of “The Point,” or Rhettsbury. The next time you’re strolling down Hasell Street, I recommend pausing in front of the old Rhett mansion at No. 54 to reimagine the scene. Though crowded and bustling today, that site was once a sort of genteel oasis lodged in a picturesque garden facing the morning sun rising over the Cooper River.

[1] Gertrude E. Meredith, The Descendants of Hugh Amory, 1605–1805 (London: Cheswick Press, 1901); Walter Edgar and N. Louise Bailey, eds., Biographical Directory of the South Carolina House of Representatives, volume 2 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1977) 37–38.

[1] Gertrude E. Meredith, The Descendants of Hugh Amory, 1605–1805 (London: Cheswick Press, 1901); Walter Edgar and N. Louise Bailey, eds., Biographical Directory of the South Carolina House of Representatives, volume 2 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1977) 37–38.

[2] Details of Amory’s property acquisitions in this area are included in Sarah Rhett, administratrix of the estate of Jonathan Amory, to Bently Cooke, planter, enfeoffment, 16 February 1708/9, in Charleston County Register of Deeds (hereafter RoD), book A: 188–96; Bently Cooke to William Rhett, enfeoffment, 16 April 1711, RoD A: 198–201, and in the property conveyances mentioned below.

[3] The machinations of Sarah and William Rhett are described in George Winston Lane, “The Middletons of Eighteenth Century South Carolina: A Colonial Dynasty, 1678–1787” (Ph.D. diss., Emory University, 1990), 77, 120–26.

[4] The will of William Rhett, dated 6 July 1722 and recorded on 7 February 1722/3, can be found in WPA transcript volume 1 (Will Book 1722–1724), pp. 12–15, in the South Carolina History Room at CCPL. Sarah Rhett’s prenuptial marriage settlement, made on 26–27 February 1727, is described in Parker Quince and Susannah, his wife, to John Davis, lease and release, 29–30 December 1773, in RoD I4: 187–202. Her marriage to Trott on 4 March 1727/8 appears in A. S. Salley Jr., ed., Register of St. Philip’s Parish, Charles Town, South Carolina, 1720–1758 (Charleston, S.C.: Walker, Evans & Cogswell, 1904), 158.

[5] Nicholas Trott and Sarah, his wife, to Rev. Alexander Garden and Joseph Wragg, lease and release in trust, 16–17 April 1734, RoD OO: 279; South Carolina Gazette (hereafter SCG), 29 August 1743.

[6] Act No. 719, “An Act for confirming and establishing a public Street from the North Bounds of Charles Town, to the North End of the Bay of the said Town; and for building a Bridge over the Marsh at the North End of the said Bay, and assessing the Lands and Improvements of the several Persons therein named towards defraying the Expence of the same,” ratified on 29 May 1744, was omitted from the nineteenth-century series of Statutes at Large of South Carolina, but the engrossed manuscript survives at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia. The Trotts sold lots to William Hendrick, John Scott, and Experience Howard in the early 1730s.

[7] Barnwell Rhett Heyward, “The Descendants of Col. William Rhett, of South Carolina,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 4 (January 1903): 36–74; SCG, 16 December 1745; SCG, 23 December 1745; SCG, 17 March 1746 (William Roper); SCG, 10 November 1746 (Richard Butler); SCG, 19–26 October 1747 (Richard Butler); SCG, 10–17 April 1749 (William Roper and Thomas Wright).

[8] For advertisements mentioned Lynch’s presence, see, for example, SCG, 28 April 1757 (supplement); SCG, 11–18 May 1765; South Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, 14 October 1766; SCG, 5 May 1767.

[9] Act No. 954, “An Act for impowering the Commissioners of the Streets in Charlestown, to lay out and continue old Church-street [Meeting Street] to George-street, in Ansonborough; and for building a Bridge and Causey at the North end of the Bay of Charlestown,” ratified on 18 April 1767, appears in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 7 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1840), 85–87; Act No. 985, “An Act for laying out and establishing a public Street in Ansonburgh [sic], and the parts adjacent thereto,” ratified on 23 August 1769, appears in McCord, Statutes at Large, 7: 92–93.

[10] See the aforementioned Rhett family genealogy in Heyward, “Descendants of Col. William Rhett,” SCHGM 4: 36–74.

[11] The partition and plat of the Rhett-Trott property is detailed in Parker Quince and Susannah, his wife, of Brunswick County, North Carolina, to John Davis of the same place, lease and release, 29–30 December 1773, RoD I4: 187–202. The streets were renamed by “An ordinance to ascertain and define anew the wards of the City of Charleston, and for other purposes therein mentioned,” ratified on 31 January 1806, in Alexander Edwards, comp. Ordinances of the City Council of Charleston, Passed between the 24th of September 1804, and the 1st Day of September 1807. To Which is Annexed, a Selection of Certain Acts and Resolutions of the Legislature of the State of South-Carolina, Relating to the City of Charleston (Charleston, S.C.: W. P. Young, 1807), 335.

[12] See, for example, James Clitherall’s advertisement in South Carolina and American General Gazette, 27 May–4 June 1774; that of Philotheos Chiffelle in SCG, 20 September 1773; that of Alexander Gillon in South Carolina Gazette and General Advertiser, 10 May 1783.

[13] For details of property damaged in the fire of 27 April 1838, see the Charleston Mercury, Courier, and Southern Patriot, issues of 28, 29, and 30 April 1838, and 1 May 1838.

PREVIOUS: George Washington in Charleston, 1791

NEXT: Denmark Vesey's Winning Lottery Ticket

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments