The Decline of Voter Suppression in South Carolina, 1900–1965

Processing Request

Processing Request

During the first half of the twentieth century, South Carolina’s political landscape was controlled by a single party of conservative White men who manipulated the state’s legal framework to silence dissenting voices. The campaign to dismantle barriers to Black suffrage gained steam under the “New Deal” in the 1930s and gradually undermined efforts to preserve traditions of White supremacy. Before the advent of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s, a series of legislative changes had already unlocked the door to Black voting. The end of a century of voter suppression was just around the corner.

In last week’s program, I summarized the rise of voter suppression in South Carolina from the late 1860s to the late 1890s. That thirty-year period witnessed the rise of a number of practices, policies, and laws designed to prevent citizens of African descent from exercising their constitutional right to participate in the political system. It was a turbulent and painful era in the history of the Palmetto State that culminated in an uneasy truce enforced by institutionalized discrimination.

The liberal Republican Party, supported by the state’s Black majority and a handful of White voters, was effectively shut out of South Carolina by the techniques of legal disenfranchisement enshrined in the state constitution of 1895. The use of violence and blatant intimidation were no longer necessary to ensure the supremacy of conservative White Democrats. At the turn of the twentieth century, they enjoyed a firm control over the political landscape of South Carolina and other Southern states. The discriminatory policies known as “Jim Crow” laws silenced the voices of the majority and garnered little attention from federal authorities in Washington. In the face of overwhelming obstacles, most Black citizens of the Palmetto State regarded voting as a futile and often dangerous endeavor.

The liberal Republican Party, supported by the state’s Black majority and a handful of White voters, was effectively shut out of South Carolina by the techniques of legal disenfranchisement enshrined in the state constitution of 1895. The use of violence and blatant intimidation were no longer necessary to ensure the supremacy of conservative White Democrats. At the turn of the twentieth century, they enjoyed a firm control over the political landscape of South Carolina and other Southern states. The discriminatory policies known as “Jim Crow” laws silenced the voices of the majority and garnered little attention from federal authorities in Washington. In the face of overwhelming obstacles, most Black citizens of the Palmetto State regarded voting as a futile and often dangerous endeavor.

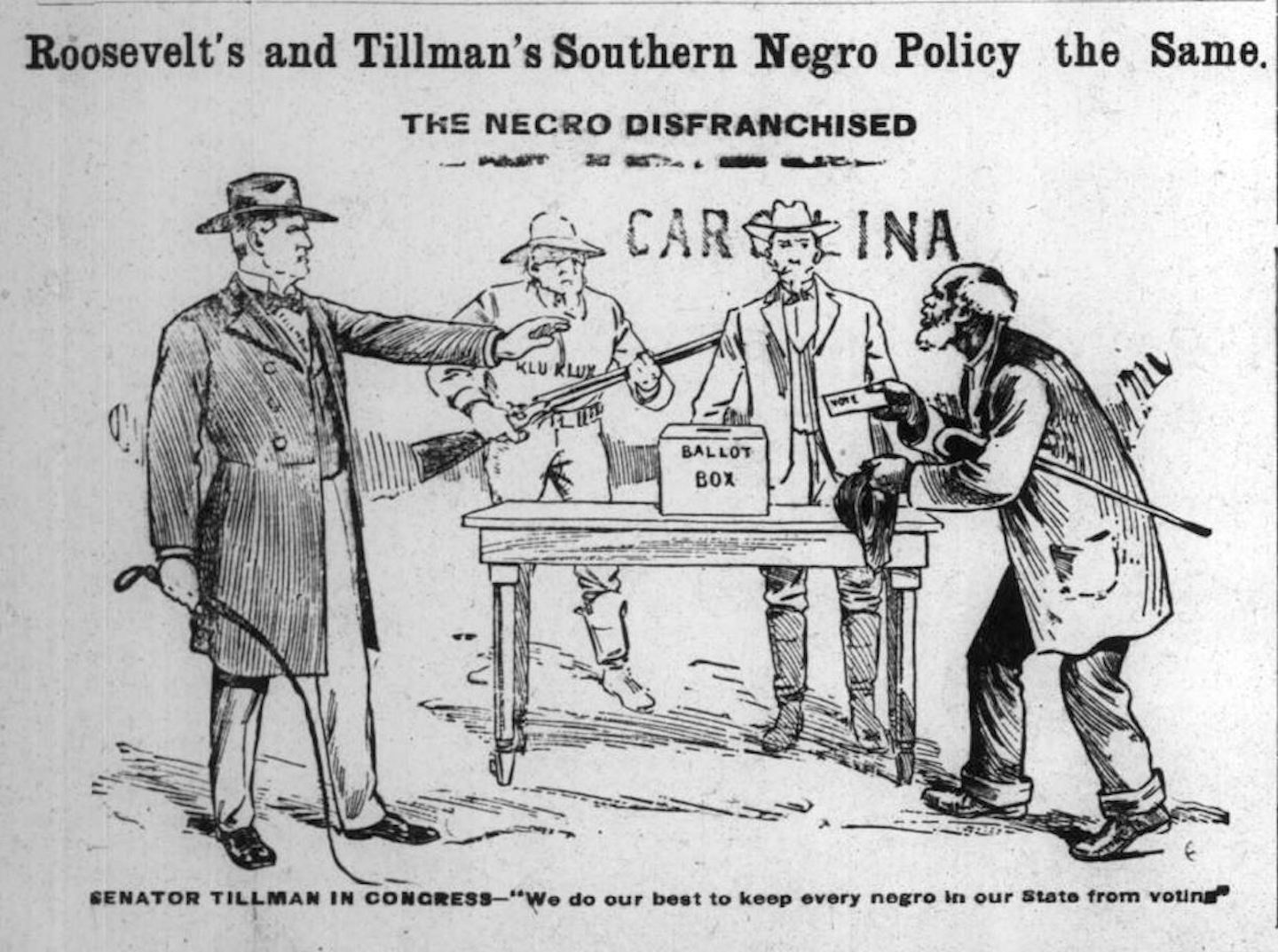

Political offices in South Carolina were won and lost at the Democratic Party’s primary elections, which the state allowed the party itself to regulate. The lack of clearly-defined rules and oversight led to abuses and manipulation, of course, which undermined public confidence in the process. In 1913, former governor Ben Tillman, now a U.S. Senator, implored White South Carolinians to reform their primary elections. Unless the Democratic Party can safeguard and “purify” their primaries, he warned, Black men might be allowed to register to vote and then participate in elections. “It would be a crime,” said Tillman, “to have the negroes mobilized and become the controlling factor in our elections. . . . Whatever else happens, let us see to it that the white people continue as they now do to be the only arbiter in our politics.”[1]

After two years of political wrangling, the South Carolina General Assembly adopted a robust set of rules and regulations in February 1915 that applied to all primary elections held by any party across the state.[2] In reality, of course, it applied only to the White Democratic Party, which ruled the state with very little political resistance. It also secured a secret ballot for South Carolina voters by providing private voting booths, but these were only for use in the White-only primary elections. Voter intimidation at general elections, which employed an open ballot system, continued unabated.

South Carolina’s laws relating to primary elections were revised and augmented multiple times between 1915 and 1938. The reform of primary election rules might not seem like an important part of the history of disenfranchisement, but it illuminates the extent to which conservative White politicians were obsessed with suppressing the participation of Black citizens. That obsession becomes increasingly clear in the acrimonious debate about primary elections in the late 1930s and early 1940s. To understand the forces that fueled that debate, we have a make a slight detour into the larger realm of national politics.

In the years after World War I, the voting demographics of the United States underwent a significant change that helped to reshape the nation’s political landscape. Between the 1910s and the 1940s, several million Americans of African descent left the segregated Southern states and moved northward. As a result of this Great Migration, Northern cities like Chicago, Philadelphia, New York, and others gained large numbers of working-class citizens. Their right to suffrage had been denied in the South, but they were allowed to vote in their new Northern homes. At the same time, the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1920, empowered millions of women to vote in all local, state, and federal elections. Thanks to the Great Migration and the 19th Amendment, the United States experienced a dramatic expansion of the voting population in the 1920s and 1930s that created a wider margin of advantage for the more populous Northern states.

The demographic shift that commenced in the 1910s also gradually reshaped the character of national party politics. Since the earliest days of Congressional Reconstruction back in 1867, most Black voters had supported the liberal Republican Party. That tradition began to change in the early twentieth century as the party courted big business and became increasingly conservative. The advent of the “New Deal” in 1933, during the first term of Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt, proved a major tipping point, however. To show support for the much-needed economic relief during the Great Depression, the majority of Black voters in Northern and Western states supported the Democratic Party in the general elections of 1936.

Democratic party leaders in the North and West welcomed the support of Black voters in the 1930s. They did not promote racial integration at first, but Northern Democrats did support efforts to uphold civil rights for all Americans. In late 1937, for example, President Roosevelt supported a bill in Congress to prosecute lynching as a Federal offense, and employed Black lobbyists to speak with senators and representatives about the matter. The inclusion of Black men in positions of influence in national politics enraged South Carolina Democrats, however, who quickly denounced their national counterparts. Senator James F. Byrnes of South Carolina, for example, criticized the Democratic National Party for giving too much power to African Americans. On the floor of the U.S. Senate in January 1938, Byrnes said “the negro has not only come into the Democratic party, but the negro has come into the greatest measure of control of the Democratic party.”[3] For conservative White voters in the South, this realization marked the beginning of the end of their allegiance to the Democratic Party.

At the South Carolina Democratic Convention in Columbia in May 1938, party members agreed to drop a provision, dating back to 1915, requiring primary voters to swear an oath to vote for the slate of candidates selected by their local, state, and national parties at the general election. Without the oath, White Democrats in the Palmetto State continued to support party candidates to fill local and state offices, but refused to support the party's presidential candidate. The purpose of this change was to punish the National Democratic Party for its support of African-American civil rights. In a stern public rebuke, the leaders of South Carolina’s Democratic Party issued the following statement: “We reaffirm our belief in White supremacy and call upon the people of South Carolina to uphold this principal and urge the national Democratic party to adhere to this principle which has long been and is today dear to Southern Democrats.”[4]

At the South Carolina Democratic Convention in Columbia in May 1938, party members agreed to drop a provision, dating back to 1915, requiring primary voters to swear an oath to vote for the slate of candidates selected by their local, state, and national parties at the general election. Without the oath, White Democrats in the Palmetto State continued to support party candidates to fill local and state offices, but refused to support the party's presidential candidate. The purpose of this change was to punish the National Democratic Party for its support of African-American civil rights. In a stern public rebuke, the leaders of South Carolina’s Democratic Party issued the following statement: “We reaffirm our belief in White supremacy and call upon the people of South Carolina to uphold this principal and urge the national Democratic party to adhere to this principle which has long been and is today dear to Southern Democrats.”[4]

Under President Roosevelt’s administration in the late 1930s and early 1940s, the Democratic National Party became increasingly liberal. At the same time, the South Carolina Democratic party became increasingly defiant about its commitment to White supremacy. Decisions in several Federal court cases forced party leaders in the Palmetto State to reflect on their position and devise new tactics to distance themselves from the national trend.

When Black citizens in New Orleans were denied the right to participate in the Louisiana Democratic Primary in 1940, they filed suit to challenge the state’s discriminatory election laws. The suit found its way to the U.S. Supreme court in the spring of 1941, where the high court decided in favor of the plaintiff. In United States v. Classic, the Supreme Court ruled that the existence of state laws regulating primary elections rendered the state’s Democratic primary to be a component of Louisiana’s official election machinery. As such, the Democratic Party was legally obliged to admit the participation of Black citizens in its primary elections.

The Supreme Court decision May 1941 sent waves of anxiety throughout the segregated South, but its impact in South Carolina was somewhat delayed. The Louisiana case applied specifically to the selection of candidates for federal offices in that state, and Democratic Party leaders in the Palmetto State seem to have believed that it would not cause them much hardship. The state Democratic Convention appointed a committee to study the issue in early 1942, and that September the committee submitted its recommendation: The state legislature should repeal existing statutes related to primary elections as a way to prevent the U.S. Supreme Court from interfering in South Carolina as it had in Louisiana.[5]

When the South Carolina General Assembly convened in January 1943, Governor Richard Manning Jefferies urged legislators to draft a bill to repeal all of the state’s laws related to primary elections, except those designed to prevent and punish fraud. The clear and acknowledged purpose of this suggestion was to strip away the same sort of rules and regulations that had provided the U.S. Supreme Court with a wedge to open Louisiana Democratic primaries to Black voters. The state’s judiciary committee backed Governor Jefferies’s plan “as a means of preserving the Democratic Party for White people.” Charleston’s News and Courier, like other state publications, endorsed this plan as a sensible way to ensure that “the Democratic Party can exist and operate as a White man’s club.”[6]

On April 3rd, 1943, the South Carolina legislature ratified a single act that repealed forty-six sections of the state’s legal code relating to primary elections, enacted between 1915 and 1938, and amended six further sections. This mass repeal was designed remove any state prescriptions about the conduct of primary elections, in order to detach the Democratic party—that state’s only party at the time—from the “machinery” of the state’s electoral system. The repeal of long-standing primary rules and regulations ostensibly rendered the South Carolina Democratic Party nothing more than a private club, which, at that time, was legally permitted to determine its own membership. Because the party’s principal objective was to deter Black voters who might want to vote for Federal candidates in the Democratic primary, the mass repeal of primary laws was post-dated to take effect on June 1st, 1944, to give the party time to revise its tactics and regulations before the larger election of 1944.[7]

Less than a year after South Carolina repealed forty-six sections of state law relating to primary elections, the United States Supreme Court handed down another blow to segregation that ruffled more feathers than the Louisiana case of 1941. In November 1943, the high court heard the case of Smith v. Allwright, in which a Black citizen in Texas was denied suffrage at a Democratic primary for local (not just federal) candidates. On April 3rd, 1944, the Supreme Court ruled that the party’s primary was an integral part of the Texas election machinery, and therefore was obliged to admit all qualified voters. Because of the nature of the primary and the state laws in question, the effect of the ruling was more general than the Louisiana case and more damaging to traditions of segregation.

In response to the decision in Smith v. Allwright, all Southern states (except Georgia and South Carolina) agreed to admit Black voters to their Democratic primaries. South Carolina party leaders were unphased and defiant at first, but soon realized their vulnerability. Lawyers pointed out that the 1943 purge of primary laws was insufficient in light of the new Supreme Court case, and references to primary elections were still littered across the state’s code of laws. Furthermore, a group of Black activists, the Negro Citizens’ Committee, stated that they were preparing to file an action to test the legality of the state’s “lily-white” primary elections. The state’s Democratic Convention was only a few weeks away, and there might be trouble. Immediate action was needed to preserve the traditions of voter suppression.[8]

To protect the party’s monopoly on state politics, Governor Olin D. Johnston issued a proclamation on April 12th, 1944, calling the state legislature back to Columbia for a brief special session. At the State House on the evening of April 14th, Governor Johnston told the members of the General Assembly that the recent Texas decision of the Supreme Court endangered their political traditions. To defend against the rise of Black voters, shouted the governor to the assembly, “it now becomes absolutely necessary that we repeal all laws pertaining to primaries in order to maintain White supremacy in our Democratic primaries in South Carolina.” Their assignment was to purge any references to primary elections that might enable the United States Supreme Court to force the state to admit Black voters to Democratic primaries. “After these statutes are repealed,” said Governor Johnston, “we will have done everything within our power to guarantee white supremacy in our primaries of our state insofar as legislation is concerned. Should this prove inadequate, we South Carolinians will use the necessary methods to retain white supremacy in our primaries and to safeguard the homes and happiness of our people.”[9]

To protect the party’s monopoly on state politics, Governor Olin D. Johnston issued a proclamation on April 12th, 1944, calling the state legislature back to Columbia for a brief special session. At the State House on the evening of April 14th, Governor Johnston told the members of the General Assembly that the recent Texas decision of the Supreme Court endangered their political traditions. To defend against the rise of Black voters, shouted the governor to the assembly, “it now becomes absolutely necessary that we repeal all laws pertaining to primaries in order to maintain White supremacy in our Democratic primaries in South Carolina.” Their assignment was to purge any references to primary elections that might enable the United States Supreme Court to force the state to admit Black voters to Democratic primaries. “After these statutes are repealed,” said Governor Johnston, “we will have done everything within our power to guarantee white supremacy in our primaries of our state insofar as legislation is concerned. Should this prove inadequate, we South Carolinians will use the necessary methods to retain white supremacy in our primaries and to safeguard the homes and happiness of our people.”[9]

During a week of non-stop activity in mid-April, 1944, state solicitors and legislators combed through the South Carolina code of laws to find any and all references to primary elections. The 1943 assembly had purged primary rules and regulations, but scores of references remained in various statutes about the administration of mundane tasks such as the nomination of forest rangers, game wardens, agricultural agents, and the like in various municipalities and counties. In short, the legislature identified 147 sections of state code that included the word “primary” and wrote 147 bills to revise each one without the offending term. Those 147 bills became statutes on April 20th, and Governor Johnston signed them into law on April 21st, the day before the beginning of the 1944 South Carolina Democratic Convention.[10]

At the end of this “11th-hour protective measure,” state leaders felt they had done their due diligence “to preserve White supremacy in the state’s Democratic primaries.” An editorial in the Charleston Evening Post congratulated the legislature for helping the state’s one-party political system “dodge the whip” of Federal interference. The suppression of Black voting was an important tradition in South Carolina, stated an editorial in the Charleston News and Courier, which offered a more explicit rationale for this viewpoint: “Were hordes of negroes admitted to white primaries in South Carolina, it would cease to be a commonwealth safe for respectable persons, white or colored, to live in. The News and Courier advocates greatly increased restrictions of suffrage. . . . Until the people shall arrive at the conclusion that voting is a privilege, not a right, and act upon it, complete political separation of the white and colored people, in party activities and primaries, must continue, must be maintained.”[11]

Having twice purged its legal code of primary election laws in 1943 and 1944, conservative White Democrats in South Carolina convinced themselves that they would be able to maintain political supremacy in the state and continue to exclude Black voters from future elections. The inevitable legal challenge came in 1947, when a Black citizen denied suffrage at the 1946 Democratic primary filed suit in Federal court. The case of Elmore v. Rice fell to Judge Julius Waties Waring, a Charleston native recently awakened to the injustice of racial segregation. When the chairman of the South Carolina Democratic party testified that the organization was simply a private club and not an integral part of the state’s election machinery, Judge Waring called his argument “pure sophistry.” The judge ruled against the White Democrats, and instructed the party to end its discriminatory practices. In a bold decision for a White Charlestonian of that era, Waring stated that “racial distinctions cannot exist in the machinery that selects the officers and lawmakers of the United States, and all citizens of this state and country are entitled to cast a free and untrammeled ballot in our elections.”[12]

In the wake of Elmore v. Rice in 1947, South Carolina’s Democratic Party could no longer prevent the participation of Black voters in primary elections. This change exacerbated existing rifts in the Democratic party and contributed to the rise of the splinter Dixiecrat Party. In terms of voting rights, however, there were now just three lingering obstacles to the regular exercise of Black suffrage in South Carolina. The poll tax requirement continued, as did and the subjective literacy tests and the tradition of voter intimidation facilitated by the absence of a secret ballot at general elections. Under increasing pressure from the Federal government and national party politics, the South Carolina legislature reluctantly moved to dismantle the remnants of blatant racism from its election laws.

In the wake of Elmore v. Rice in 1947, South Carolina’s Democratic Party could no longer prevent the participation of Black voters in primary elections. This change exacerbated existing rifts in the Democratic party and contributed to the rise of the splinter Dixiecrat Party. In terms of voting rights, however, there were now just three lingering obstacles to the regular exercise of Black suffrage in South Carolina. The poll tax requirement continued, as did and the subjective literacy tests and the tradition of voter intimidation facilitated by the absence of a secret ballot at general elections. Under increasing pressure from the Federal government and national party politics, the South Carolina legislature reluctantly moved to dismantle the remnants of blatant racism from its election laws.

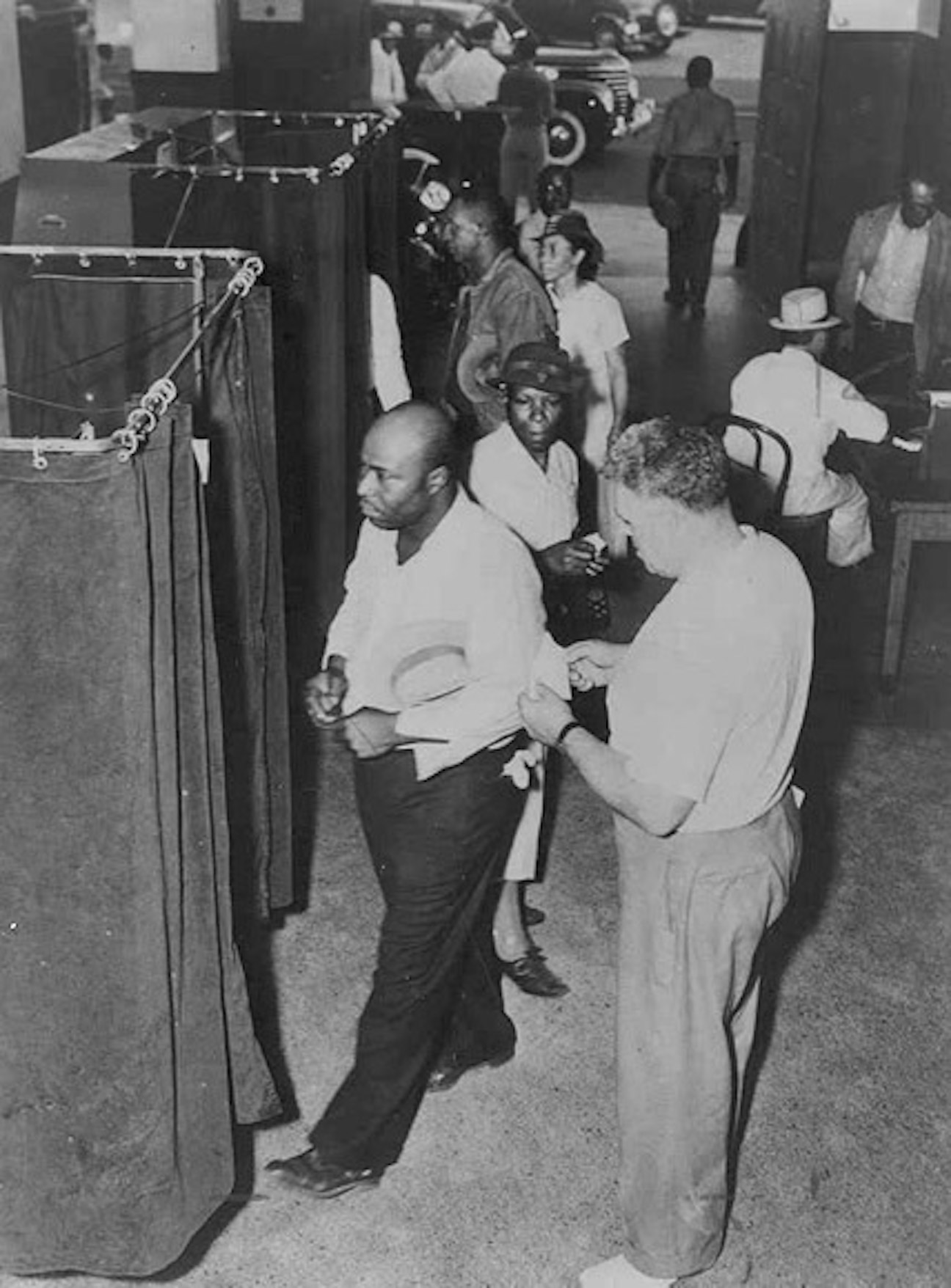

In April 1950, Governor Strom Thurmond signed an omnibus bill that completely revised South Carolina’s laws pertaining to both primary and general elections. It included provisions to create more complete and uniform ballots to be issued to all voters at general elections. Prior to this time, voters were obliged to ask for either a Democratic ballot or a Republican ballot, which request opened them to potential scorn and intimidation. The new law also required polling places to provide private booths at all elections in which South Carolinians could finally cast a secret ballot. As a nod towards the increasing national pressure on voting rights, the state election law of 1950 made it illegal to “threaten, mistreat, or abuse any voter, with a view to control or intimidate him in the free exercise of his right of suffrage.”[13]

South Carolina’s revised election law of 1950 appears to represent a complete reversal of traditional tactics designed to suppress the participation of Black voters, but elements of discrimination remained. The new law redefined the requirements for candidacy in a manner that made it very difficult for Black candidates to get their names on any ballots in the state. The purpose of this change, according to an op-ed piece in the News and Courier, was “to perpetuate one-party control, to prevent the rise of other parties,” and to ensure that the Democratic primary was the only “real election” in South Carolina.[14]

Voter registration across South Carolina increased slightly in the wake of the 1950 changes to the state’s election law. Building on this progress, the ballots issued in November of that year asked voters to decide whether the state’s ancient poll tax should be repealed. Some national politicians had been advocating throughout the 1940s for the repeal of all poll tax laws, but the conservative Southern states had stubbornly resisted. White Democrats in South Carolina argued that the poll tax was more of a nuisance than an obstacle to voting, but noted privately that it was a useful tool that fastidious poll workers could use to exclude Black voters. The writing was on the wall for progressive change, however, and there were bigger battles to be fought elsewhere. The response to the 1950 state referendum was overwhelmingly affirmative, and the legislature responded quickly. In February 1951, the South Carolina General Assembly ratified an amendment to the state constitution to repeal the traditional poll tax that was first imposed in 1756.[15]

Following the amendment of 1951, the only real obstacle to widespread Black voting in South Carolina was the subjective literacy test established by the state constitution of 1895. Sadly, literacy was still very much an issue in our community during the early twentieth century. As in other Southern states once committed to the institution of slavery, South Carolina’s public educational system was segregated and patently unequal. White students generally enjoyed educational resources, facilities, and opportunities that were routinely denied to Black students. In an economic environment poisoned by policies of racial segregation, many Black students were obliged to leave school early to help support their families. In short, the policies of segregation that blunted economic progress in the Black community also stunted the acquisition of the educational skills necessary to break the cycle of injustice.

As most Americans know, the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education was a transformative, watershed moment in the history of the United States. After decades of denial and apathy, the highest court in the nation decreed that the long-standing segregationist policy of “separate but equal” was fundamentally unconstitutional. Racial integration and equal protection under the law did not flow across the Southern states in the immediate aftermath of the Supreme Court ruling, however. Rather, the success of Brown v. Board of Education launched a widespread grass-roots campaign to secure the rights now guaranteed by the federal government. Between 1955 and 1968, advocates of this Civil Rights Movement, as we now call it, boldly challenged the traditions of segregation and gradually transformed national attitudes.

During the turbulent years of the nation’s second great era of Civil Rights campaigning, the National Democratic Party continued its trend towards becoming increasingly liberal and progressive, while the National Republican Party continued its increasingly conservative trajectory. By the end of the 1960s, the characteristics that we presently associate with these parties had solidified. In short, between 1930 and 1970, the two dominant political parties in the United States switched sides of the political spectrum. The motivations for this exchange were abundantly clear in countless newspaper editorials of that period. The Democratic Party gradually shifted to the left by embracing Black voters and their civil-rights issues, while the Republican party moved to the right by embracing conservative White voters who supported segregation.

By the early 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement reached a point of no return. Policies and practices to enforce segregation gradually disappeared in cities and states across the South. The Charleston County Public Library, for example, integrated its various library branches between 1960 and 1963. There was still much work to be done, of course, but the momentum for progress was undeniable. A century of efforts to secure the right of suffrage for Americans of African descent reached a climax with two Federal actions taken in 1964 and 1965. The first was the ratification of the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in January 1964. This amendment prohibited the United States government or any state to deny citizens their right to vote “by reason of failure to pay any poll tax or other tax.”

The principal achievement came eighteen months later, however. In August 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed “An Act to Enforce the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and for other purposes,” better known as the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (79 Stat. 437). This law finally suspended the literacy tests that South Carolina and other states had adopted in order to suppress Black suffrage. But there was a small catch: the 1965 Voting Rights Act did not apply evenly to the nation as a whole. The prohibition against literacy qualification tests initially applied only to those states and/or counties in which less than fifty percent of the voting-age citizens had registered or voted in the last general election in November 1964. Registrars in such states and/or counties would proceed to register citizens who met all qualifications, regardless of previous literacy tests. South Carolina met the “automatic trigger” provisions of the federal act, and the registration of Black citizens in the Palmetto State increased dramatically as a result.[16]

The principal achievement came eighteen months later, however. In August 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed “An Act to Enforce the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and for other purposes,” better known as the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (79 Stat. 437). This law finally suspended the literacy tests that South Carolina and other states had adopted in order to suppress Black suffrage. But there was a small catch: the 1965 Voting Rights Act did not apply evenly to the nation as a whole. The prohibition against literacy qualification tests initially applied only to those states and/or counties in which less than fifty percent of the voting-age citizens had registered or voted in the last general election in November 1964. Registrars in such states and/or counties would proceed to register citizens who met all qualifications, regardless of previous literacy tests. South Carolina met the “automatic trigger” provisions of the federal act, and the registration of Black citizens in the Palmetto State increased dramatically as a result.[16]

Many White conservatives in South Carolina objected to the federal act of 1965 in general, and complained specifically about the Palmetto State being singled out for its stubborn resistance to Black suffrage. In newspaper articles and political speeches across the state, conservatives argued that the Voting Rights Act was unconstitutional because it prohibited the use of literacy tests in some areas (predominantly in the South) while allowing them to continue in other areas of the county.[17] Such statements smacked of bitter resentment, but they made a valid point. Congress addressed this issue in a revision of the Federal law in June 1970 that prohibited “tests or devices” uniformly in all states.[18]

Let’s conclude this conversation about the rise and fall of voter suppression with a brief summary: The advent of Black suffrage in South Carolina in 1867 infuriated the state’s conservative White minority which sought to perpetuate the traditions of White supremacy established by the institution of slavery. Through a sustained campaign of fraud, intimidation, and violence, White conservatives defied federally-protected civil rights and regained control of state and local politics in 1877. They secured their supremacy by enacting a number of laws between 1878 and 1896 that created a very high and effective barrier to Black suffrage. Changes in national demographics and political attitudes began to push against that barrier in the 1930s, however, and legal challenges forced a series of gradual changes. Between 1943 and 1951, the South Carolina legislature dismantled most of the laws intended to maintain the state’s traditions of White supremacy. Obstacles to equality still existed, of course, but they were sufficiently diminished to encourage many Black Americans to mobilize and lobby for the complete eradication of the traditional methods of voter suppression. The great push for universal civil rights in the United States that commenced in the mid-1950s reached a climax with the adoption of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. That imperfect law, aided by similar legislation of the era, marked the culmination of a century of efforts to recognize Americans of African descent as full citizens of this republic.

Vestiges of institutionalized discrimination and inequality continued in South Carolina after 1965, of course, and continue to exist in the twenty-first century. As a historian, I believe it’s imperative that citizens understand the deep background behind the issues that continue to disturb and divide our community. The right to vote is the right to exercise one’s political voice, and I encourage all citizens to learn more about our shared past in order to strengthen their voices in present and future conversations.

Selected Titles For Further Reading:

Bartlett, Bruce R. Wrong on Race: The Democratic Party’s Buried Past. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Frederickson, Kari. The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932–1968. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Gergel, Richard. Unexampled Courage: The Blinding of Sgt. Isaac Woodard and the Awakening of President Harry S. Truman and Judge J. Waties Waring. New York: Macmillan, 2019.

Williams, Chad, et al., eds. The Charleston Syllabus: Readings on Race, Racism, and Racial Violence. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2016.

[1] Charleston Evening Post, 4 August 1913, page 6, “Tillman Against Probing Primary.”

[2] “An Act to Regulate the Holding of All Primary Elections and the Organization of Clubs in Cities Containing 40,000 Inhabitants or More,” ratified on 16 February 1915, in Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina, Passed at the Regular Session of 1915 (Columbia, S.C.: Gonzales and Bryan, 1915), 163–74.

[3] Charleston News and Courier, 12 January 1938, pages 1, 2, “Byrnes Vigorously Assails ‘Humiliating’ Lynch Measure.”

[4] News and Courier, 29 January 1938, page 5, “Under Rule 32”; Evening Post, 19 May 1938, page 1, “Pledge Will Not Be Asked.”

[5] News and Courier, 28 May 1941, page 4, “Negroes in Southern Primaries”; News and Courier, 21 February 1942, page 4, “Warning to Officials”; News and Courier, 14 May 1942, page 4, “Negro Vote Case Cited”; News and Courier, 7 March 1943, page 2B, “Change Near in Vote Laws.”

[6] News and Courier, 13 January 1943, page 3, “Governor Urges Payment on State’s Debt, Short Session and End of One Mill Levy”; News and Courier, 15 January 1943, page 4, “Shall We Plead Guilty”; News and Courier, 10 February 1943, page 7, “Election Statute Repeal Is Favored”; News and Courier, 24 February 1943, page 3, “Primary Election Change Favored”; News and Courier, 1 March 1943, page 4, “You Can’t Avoid the Issue”; News and Courier, 7 March 1943, page 2B, “Change Near in Vote Laws.”

[7] “An Act to Repeal Sections 2352, 2353, 2354, 2355, 2359, 2360, 2361, 2362, 2363, 2365, 2366, 2367, 2368, 2369, 2370, 2373, 2374, 2375, 2376, 2377, 2378, 2379, 2380, 2381, 2382, 2404, 2405, 2407, 2408, 2409, 2410, 2411, 2412, 2413, 2414, 2415, 2416, 2416-1, 2417, 2418, 2418-1, 2418-2, 2418-3, 2418-4, 2418-5, Volume 2, Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1942, Relating to the Conduct of Primary Elections, and to Repeal an Act Entitled, ‘An Act to Amend Sections 2358 and 2406, Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1932, So As to Further Provide for the Enrollment and Voting of Persons Serving in the Armed Forces of the United States or Employed in Government Operated Defense Establishments or Reservations,’ Knowns as Act No. 737 of the Acts of 1942,” ratified on 3 April 1943, in South Carolina, Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina, Regular Session of 1943 (Columbia, S.C.: n.p., 1943), 84–85. Note also that the state also passed “An Act to Provide for the Organization of Political Parties to Authorize Primary Elections and to Further Provide for Appeals therein,” on 5 March 1943, which is found in the same volume of Acts and Joint Resolutions, page 28. This law was to go into effect on 1 June 1944, but it was repealed in April 1944 (see below).

[8] Evening Post, 4 April 1944, page 12, “White Political Leaders in State Seem Unworried”; News and Courier, 6 April 1944, page 1, “One State Act Could Permit Negro Voting”; News and Courier, 6 April 1944, page 1, “Johnston Sure of White Democratic Supremacy”; News and Courier, 15 April 1944, page 1, “State Negroes to Form Party.”

[9] News and Courier, 13 April 1944, pages 1–2, “Johnston Calls Legislative Session Friday”; News and Courier, 14 April 1944, page 1, “Solicitors Search for Danger Spots in Primary Laws”; Evening Post, 14 April 1944, page 9B, “Bills Will Be Ready for State Lawmakers”; News and Courier, 15 April 1944, page 1, “Governor Shouts to Assembly That White Supremacy Must Be Maintained in Primaries”; Evening Post, 17 April 1944, page 4, “No Deep Mystery.”

[10] See South Carolina, Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina, Regular Session of 1944 and Extra Session of 1944 (n.p.: n.p., [1944]), 2215–2347. Each of the 147 acts was made effective “upon its approval by the governor,” which took place on 21 April 1944.

[11] News and Courier, 21 April 1944, page 1, “Extra Session Finishes Task; Primary Safe”; Evening Post, 21 April 1944, page 4, “Warren Points the Way”; Evening Post, 21 April 1944, page 15, “State Democrats Feel Primary Is Safe for Whites”; News and Courier, 10 June 1944, page 4, “Necessities of the Case.”

[12] For discussion of Elmore v. Rice, see Richard Gergel, Unexampled Courage: The Blinding of Sgt. Isaac Woodard and the Awakening of President Harry S. Truman and Judge J. Waties Waring (New York: Macmillan, 2019), 178–87.

[13] South Carolina, Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina, Regular Session of 1950 (Columbia, S.C.: n.p., 1950), 2059–2116; News and Courier, 21 April 1950, page 1, “Thurmond Signs Omnibus Election Law”; News and Courier, 25 April 1950, page 1, “Election Law Gives Secret Ballot.”

[14] News and Courier, 27 April 1950, page 1, “All Parties Under Election Law”; News and Courier, 27 April 1950, page 1, “General Assembly Endorses Judge Waring’s Opinions.”

[15] News and Courier, 6 July 1950, page 4, “Registration Shows Increase”; Evening Post, 10 November 1950, page 4, “Poll Tax Verdict”; “An Act to Ratify an Amendment to Article II, Section 4, of the Constitution of South Carolina, 1895, Which Provides for the Elimination of the Requirement of the Payment of Poll Tax before Voting in Elections,” ratified on 13 February 1951, in South Carolina, Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina, Regular Session of 1951 (Columbia, S.C.: n.p., 1951), 24–25; News and Courier, 14 February 1941, page 6, “General Assembly Ratified Poll Tax Amendment.”

[16] News and Courier, 7 August 1965, page 1, “Enforcement of Voting Law Pledged.”

[17] See, for example, Evening Post, 11 August 1965, page 2B, “The New Voting Law,” and “The Voting Rights Law and the Constitution.”

[18] See 84 Stat. 314, “An Act to extend the voting Rights Act of 1965 with respect to the discriminatory use of tests and devices,” ratified on 22 June 1970. This law states that “no citizen shall be denied, because of his failure to comply with any test or device, the right to vote in any Federal, state, or local election conducted in any state or political subdivision of a state.”

NEXT: Charleston’s Contested Election of 1868

PREVIOUSLY: The Rise of Voter Suppression in South Carolina, 1865–1896

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments