Abraham the Unstoppable, Part 4

Processing Request

Processing Request

Stricken with the deadly smallpox, Abraham convalesced in Charleston in the late winter of 1760 before embarking on another round-trip journey carrying official messages through the dangerous Cherokee territory. Having witnessed grotesque scenes of death and misery both in town and among the frontier forts, Abraham returned to Charleston to see the wheels of government slowly turning towards the legal confirmation of his freedom from slavery.

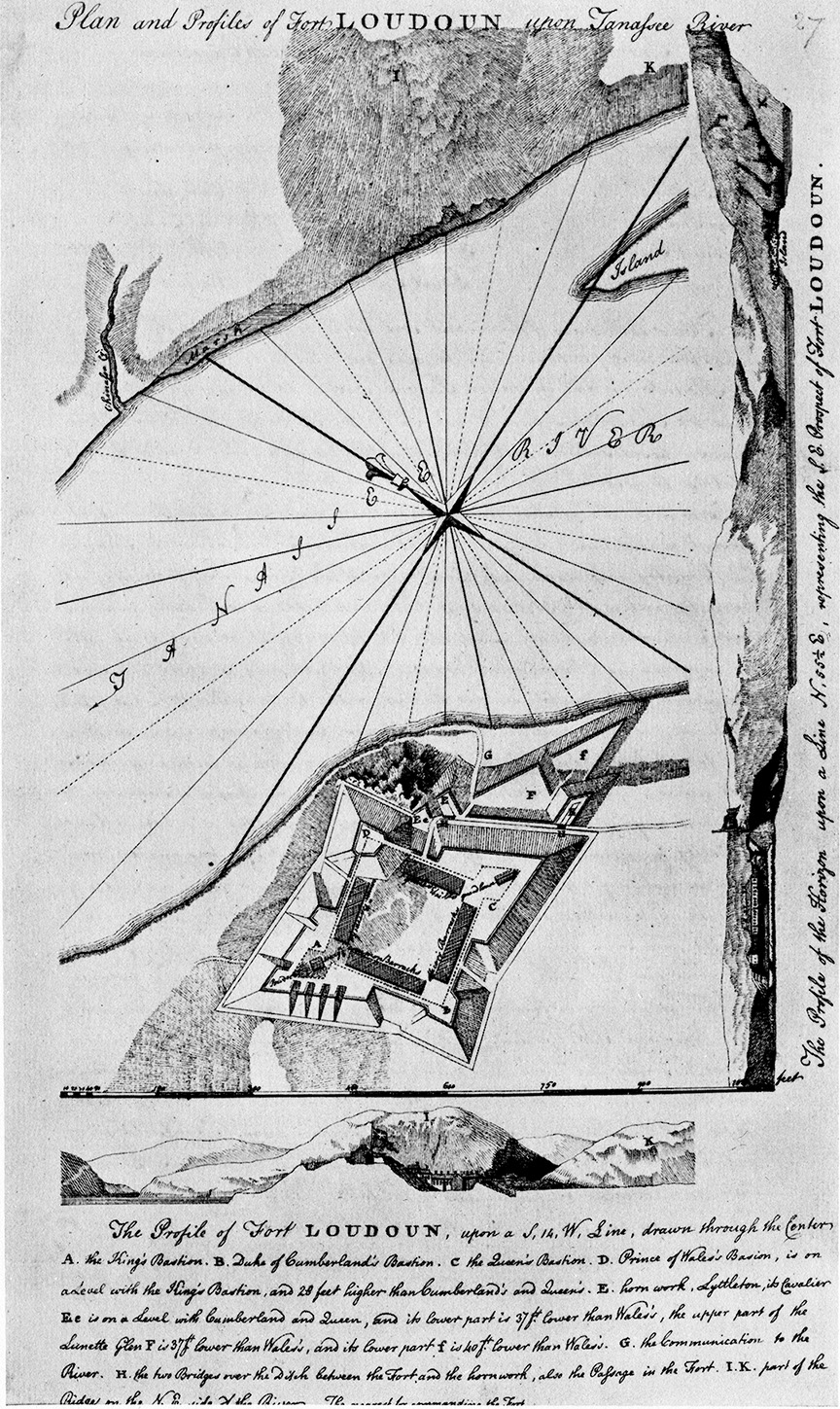

In mid-February 1760, Abraham had just completed a dangerous and grueling solo trek covering more than 400 miles from Fort Loudoun, in modern eastern Tennessee, to Charleston. By delivering a cache of important letters from the commanders of frontier outposts to the governor of South Carolina, per an agreement with Capt. Paul Demeré, he had ostensibly earned his freedom from slavery. As I explained in our last episode, however, Abraham’s official manumission from slavery would have to be confirmed by the provincial legislature. In the meantime, the news of Abraham’s heroic deed spread throughout Charleston, and he enjoyed a sort of nominal freedom while he remained in the capital city.

Abraham was no stranger to Charleston, having visited the city many times in the past as he and his master, Samuel Benn, delivered deerskins for export and collected trade goods to barter with the Cherokee. Those regular trips to town undoubtedly involved brief stays at something like a local tavern, but the details of their usual accommodations are not recorded in any surviving documents. Along the Broad Path leading into Charleston (now King Street), there were several inns, as they were sometimes called, identified by their distinctive signs posted along the road. During the era of the Cherokee War, country visitors could find a room and a stable for their horses at the sign of the Bear, the sign of the Crown, the sign of the White Horse, or the sign of the Peacock. Back in December of 1757, Samuel Benn was heard to say that he had made the long trip to Charleston “hundreds” of times. Perhaps he had a favorite place to stay, and had even formed a cordial relationship with the proprietor over the years. Perhaps Abraham used that business contact to secure a room, a bed, or at least a shelter.

In previous trips to Charleston, Samuel Benn was responsible for finding room and board for his enslaved assistant. Now, as a free man traveling alone, however, Abraham had to fend for himself. Half of the town’s population of approximately 10,000 souls were enslaved people of African descent, but there was a tiny minority of people like Abraham, known as “free persons of color.” We have no official population statistics for urban Charleston in 1760, but an unofficial 1770 tabulation counted just twenty-four “Free Negroes, Mulattoes, &c.” in the capital, and just 135 in South Carolina outside of Charleston.[1] It’s possible that Abraham might have reached out to one of these free people for advice or assistance, but finding such a person in the crowded, dirty city must have been a challenge. And his efforts to find hospitality in the capital at that moment were complicated by the fact that he was a relative stranger who was carrying the smallpox virus.

The dreaded infectious disease had first appeared among the Charleston soldiers encamped at Fort Prince George in December of 1759, and returned with them to Charleston in early January 1760. By February, the town was in a state of panic about both the Cherokee war and the deadly illness. Citizens, physicians, and politicians argued over the scientific and legal merits of the controversial process of inoculation, the deliberate introduction of material from smallpox pustules into the skin of a healthy person. Inoculation was believed to lessen the severity of the disease, but the process was not without risk. The fevers associated with the disease were often fatal, and the tiny pustules that covered the victim’s body left permanent, often disfiguring scars. Contrary to local law, nearly two-thirds of Charleston’s population sought inoculation in the early months of 1760 as the town writhed in agony. On April 19th, the South Carolina Gazette stated that the spread of the disease was “pretty well over” within the town, after approximately 380 whites and 350 blacks, totaling about 7% of the population, had died.[2]

The dreaded infectious disease had first appeared among the Charleston soldiers encamped at Fort Prince George in December of 1759, and returned with them to Charleston in early January 1760. By February, the town was in a state of panic about both the Cherokee war and the deadly illness. Citizens, physicians, and politicians argued over the scientific and legal merits of the controversial process of inoculation, the deliberate introduction of material from smallpox pustules into the skin of a healthy person. Inoculation was believed to lessen the severity of the disease, but the process was not without risk. The fevers associated with the disease were often fatal, and the tiny pustules that covered the victim’s body left permanent, often disfiguring scars. Contrary to local law, nearly two-thirds of Charleston’s population sought inoculation in the early months of 1760 as the town writhed in agony. On April 19th, the South Carolina Gazette stated that the spread of the disease was “pretty well over” within the town, after approximately 380 whites and 350 blacks, totaling about 7% of the population, had died.[2]

The details of Abraham’s battle with the smallpox are a mystery, but he had to have laid down and suffered somewhere in the town. Someone brought him food and water while the fever worked its way through his body, and someone nursed him back to health. Without documentary evidence, however, we can only speculate about the specifics of who and where. Perhaps he endured the disease while sheltered in a stable or a kitchen house belonging to one of Samuel Benn’s business acquaintances. Perhaps he managed to secure a bed in one of the several private smallpox “hospitals” that were opened by Charleston physicians in an effort to quarantine the numerous urban victims. Perhaps the governor, to whom Abraham had faithfully delivered messages from the distant frontier forts, took pity on the man and ordered him to shelter in one the outbuildings behind his rented residence, the Pinckney mansion on East Bay Street. It might seem unlikely that the royally-appointed governor would extend such an invitation to a poor, nominally-enslaved man in 1760, but I mention this possibility because at that moment the governor was packing his bags for departure.

In mid-February, South Carolina’s governor, William Henry Lyttelton, learned that his superiors in London had appointed him to be governor of Jamaica, effective immediately. Lyttelton, age thirty-five, was the sixth son of a wealthy English politician who had inherited nothing from his family. Like many of his social sphere, he was obliged to follow a career as a government placeman among the American colonies. His imminent departure from South Carolina was bound to cause some administrative difficulties during this time of military crisis, but Lyttelton’s inept handling of the Cherokee business probably softened the impact of his removal from the scene.

More important to the present story was the question of Abraham’s manumission. By successfully completing his mission to deliver dispatches to the governor, he had ostensibly gained his freedom. Governor Lyttelton informally acknowledged this fact in mid-February, but the legal process of confirming Abraham’s manumission could not begin until the governor formally recommend his case to the Commons House of Assembly. During his final weeks in Charleston, however, Lyttelton was too busy settling his local affairs and packing his belongings to remember the enslaved messenger. The governor announced his eminent departure to the Commons House on March 11th, and within a week had relinquished his office. He boarded the HMS Trent, then in the harbor, waited for a fair wind, and set sail for England on April 5th to receive instructions for his new administration in Jamaica.[3]

Meanwhile, in late March, William Bull II assumed the reins of government as lieutenant governor of South Carolina. The fifty-year-old son of an earlier lieutenant governor of the same name, William Bull would eventually serve as the colony’s interim executive on five separate occasions, totaling more than eight years in that office. The spring of 1760 represented his first term as lieutenant governor, but he was already a veteran politician, having served for many years as one of the governor’s advisors on His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina. In that role, Dr. Bull (he was trained as a physician) would have been privy to the details of Abraham’s recent adventure, the promise Captain Demeré made to him in January, and Governor Lyttelton’s provisional acknowledgment of his freedom. In fact, as a native of the colony, Lt. Gov. Bull probably knew more about the Cherokee situation and Indian traders like Samuel Benn than Governor Lyttelton could have learned during his four-year tenure in South Carolina. In short, the sudden transition of executive power in Charleston in the spring of 1760 did not obliterate Abraham’s path to legal manumission, but it definitely delayed the process for a while.[4]

While Abraham was laid low by the smallpox in Charleston, there were two important developments in the colony’s war against its former Indian allies. First, the wave of Cherokee violence that had commenced on February 1st near the Long Canes continued across the frontier. Abraham had seen this first hand as the rode the trail from Fort Prince George to Ninety Six, and found his master, Samuel Benn, in bandages at the latter fort. After Abraham departed Ninety Six and galloped towards Charleston, the bloodshed continued in the backcountry. On February 16th, approximately 800 Cherokee warriors surrounded Fort Prince George and demanded a conference with the fort’s commander, Lieutenant Richard Coytmore. When the commander and a few other soldiers stepped out of the fort’s front gate and began negotiations, the Cherokee leader made a signal to his men. Lieutenant Coytmore was shot in the chest, and a hail of gunfire cut down the other men. The Indians whooped in delight at the violence, while the soldiers inside the fort, both white and black, panicked in fear. Smallpox had reduced their number from nearly sixty to about forty, and now 800 angry warriors were clamoring outside for the release of their brothers held hostage inside the fort. In a confused, terrified meltdown of military discipline, the soldiers massacred nearly twenty Cherokee hostages using pistols, bayonets, tomahawks, and knives. The Indians outside became enraged, of course, but were unable to storm the fort. In the ensuing days, the bulk of the Cherokee warriors withdrew to the west, but they continued to blockade Fort Prince George and Fort Loudoun in the Overhill territory.[5]

While Abraham was laid low by the smallpox in Charleston, there were two important developments in the colony’s war against its former Indian allies. First, the wave of Cherokee violence that had commenced on February 1st near the Long Canes continued across the frontier. Abraham had seen this first hand as the rode the trail from Fort Prince George to Ninety Six, and found his master, Samuel Benn, in bandages at the latter fort. After Abraham departed Ninety Six and galloped towards Charleston, the bloodshed continued in the backcountry. On February 16th, approximately 800 Cherokee warriors surrounded Fort Prince George and demanded a conference with the fort’s commander, Lieutenant Richard Coytmore. When the commander and a few other soldiers stepped out of the fort’s front gate and began negotiations, the Cherokee leader made a signal to his men. Lieutenant Coytmore was shot in the chest, and a hail of gunfire cut down the other men. The Indians whooped in delight at the violence, while the soldiers inside the fort, both white and black, panicked in fear. Smallpox had reduced their number from nearly sixty to about forty, and now 800 angry warriors were clamoring outside for the release of their brothers held hostage inside the fort. In a confused, terrified meltdown of military discipline, the soldiers massacred nearly twenty Cherokee hostages using pistols, bayonets, tomahawks, and knives. The Indians outside became enraged, of course, but were unable to storm the fort. In the ensuing days, the bulk of the Cherokee warriors withdrew to the west, but they continued to blockade Fort Prince George and Fort Loudoun in the Overhill territory.[5]

During the first week of April, a small fleet of British warships arrived carrying reinforcements sent from New York in response to Governor Lyttelton’s request made in early February. The fresh troops included Colonel Archibald Montgomery with six companies of the Royal Scots (1st Regiment of Foot) and six companies of Montgomery's Highlanders (77th Regiment of Foot). While Colonel Montgomery disembarked from the HMS Albany in Charleston to confer with Lt. Gov. Bull, six transport ships sailed up the Cooper River and unloaded the soldiers at Mr. Brailsford’s plantation, called The Retreat (now the northern part of the old Charleston Naval Base). From there they marched to Monck’s Corner and camped until their commander was ready to march westward. In the interim, their numbers were augmented by 335 horse-mounted South Carolina Rangers and one hundred men of the newly-formed South Carolina Provincial Regiment of Foot.[6]

By the middle of April, 1760, Abraham was sufficiently recovered from his bout with smallpox to meet with Lt. Gov. William Bull at his office in the Council Chamber (now the site of the Old Exchange Building). Working through an intermediary like John Bassnett, the messenger of His Majesty’s Council, Bull might have summoned Abraham to discuss his role in the Cherokee affair, or Abraham might have sent word that he was available for hire. The details of their conversation are lost, and were probably never written down, but the outcome of their parley is clear. Lieutenant-Governor Bull asked Abraham to return to the Cherokee territory, carrying letters from him to the commanders of both Fort Prince George and Fort Loudoun. Abraham accepted the task, and our “Negro” woodsman set out on a second hazardous journey into hostile territory.

What could have motivated Abraham to make another journey back to Fort Loudoun? On the one hand, Abraham’s decision to undertake a return mission of more than four hundred miles to the west was motivated by practical needs. He was now a nominally free man, beholden to none, but he was also without employment and without a fixed abode. In urban Charleston, he was somewhat out of his element and in need of some means of earning a livelihood. Furthermore, Abraham was not the only skilled delivery man in town. There were several other express riders carrying government messages between Charleston and the Cherokee forts at this time, including such men as Henry Lucas, Aaron Price, and one Mr. Dempsey. These were paid white men, however, so their motivation must have been a bit different from that of our protagonist.[7] Perhaps Abraham sought an audience with the lieutenant governor and offered his services to the government, though this time for pay.

On the other hand, it’s possible that the government recruited Abraham for this mission specifically because of his proven reputation as a fearless delivery man. The lieutenant governor might have flattered him in order to secure his cooperation. “Your skills as a backwoodsman are well known,” Bull might have said, “and the present, distressing circumstances in the backcountry require our fullest attention. It is imperative that we maintain communication with our soldiers on the frontier.” Colonel Montgomery and his army of 1,600 men were ready to march towards Fort Prince George, and someone needed to carry this information westward immediately, in order to give the men of that fort, as well as those at Fort Loudoun, hope of future relief. Abraham, one could argue, knew the route through the distant Cherokee territory better than any other man then in the service of His Majesty’s government in South Carolina.

It’s also possible that the lieutenant governor might have used Abraham’s status as a provisionally-free man to the government’s advantage. Governor Lyttelton had neglected to mention Abraham’s case to the legislature before he departed the colony, but Lt. Gov. Bull now had the power to advance that important legal matter in the present assembly. If Abraham would agree to undertake a second dangerous mission, Bull might have bargained, then the lieutenant governor would promise to recommend to the Commons House that they should officially purchase Abraham’s freedom from slavery.

Whatever his motivation, we know that Abraham departed Charleston on horseback sometime around April 22nd—just ahead of Colonel Montgomery’s slow-moving army—and arrived at Fort Prince George on April 29th. We know the date of his arrival because of a newspaper report describing the scene he stumbled into that day. A roving band of seven Chickasaw warriors, allied with the British, were headed toward the fort when they surprised a group of Cherokee Indians picking strawberries in a field about two miles from the fort. The berry pickers immediately sounded the alarm and ran towards the nearest Cherokee village, called Sugar Town by the English, and nine mounted warriors rode out to attack the interlopers. In the ensuing clash, the Cherokee killed three of the Chickasaw and drove the survivors into the nearby forest.

When Abraham approached the fort on the evening of April 29th, he found two of the Chickasaw hiding in the forest, waiting for an opportunity to sneak into the fort. The Cherokee were still in the habit of surrounding the fort each night to prevent the garrison from sending or receiving communications, as they had been doing since January, but then Abraham arrived on the scene and managed to find a way in. Perhaps using a pre-arranged signal, like a bird call, Abraham escorted the Indian allies through the gates of the fort under the cover of darkness. The next evening, the surviving Chickasaw warriors along “with some of our people” from Fort Prince George set out for revenge on the Cherokee. I’d like to believe that Abraham was among the members of that covert operation on April 30th, but in reality we have no record of their names. During the night, the party snuck into the center of the nearby Cherokee town of Keowee—the same town from which Abraham had stolen a horse in early February—and set fire to the communal “Town House” and about half a dozen other buildings before fleeing back to the safety of the fort.[8]

After a short rest at Fort Prince George, Abraham continued his northwest journey through the “Four and Twenty Mountains” and arrived at Fort Loudoun approximately one week later, around May 10th. A later newspaper notice stated that at the time of his arrival, “the Upper Cherokee still pretended to be desirous of peace; yet they had placed centinels [sic] at certain distances around the fort, so that he [Abraham] found it difficult to get in [to the fort], even in the night.”[9] By this time, the people within the strong, palisaded walls, including a number of women and children as well as soldiers, were “very miserable, and their provisions [had been] reduced to two ounces of rotten meat, and a pint of corn per day, at which allowance they had not more than would last them six weeks.”[10] Abraham brought the happy news that a slow-moving army of more than 1,600 soldiers and a wagon train of supplies were on their way up from the Lowcountry. With any luck, they might reach Fort Loudoun by the beginning of July, some two months in the future.

After a short rest at Fort Prince George, Abraham continued his northwest journey through the “Four and Twenty Mountains” and arrived at Fort Loudoun approximately one week later, around May 10th. A later newspaper notice stated that at the time of his arrival, “the Upper Cherokee still pretended to be desirous of peace; yet they had placed centinels [sic] at certain distances around the fort, so that he [Abraham] found it difficult to get in [to the fort], even in the night.”[9] By this time, the people within the strong, palisaded walls, including a number of women and children as well as soldiers, were “very miserable, and their provisions [had been] reduced to two ounces of rotten meat, and a pint of corn per day, at which allowance they had not more than would last them six weeks.”[10] Abraham brought the happy news that a slow-moving army of more than 1,600 soldiers and a wagon train of supplies were on their way up from the Lowcountry. With any luck, they might reach Fort Loudoun by the beginning of July, some two months in the future.

During the early months of 1760, Cherokee warriors from the Overhill Towns near Fort Loudoun had been waging war against the white traders and settlers on the frontier. Those that were not killed, scalped, and dismembered were captured and taken back to the various Indian towns. There, the male prisoners were subjected to ritual torture and death by fire, while the white women and children were generally traded as chattel slaves. Around the time that Abraham arrived at Fort Loudoun in early May, Capt. Paul Demeré “ransomed a [white] woman and three children from the Indians.” Despite his humane intercession, the Charleston newspaper later reported, “the poor woman had been so cruelly used that she died soon after.”[11]

On May 15th, when “all seemed quiet in the [Upper Cherokee] Nation,” Abraham departed Fort Loudoun and once again headed southeast towards the coastline. Within a week, he arrived at Fort Prince George. A few days later, he passed by the main body of Colonel Montgomery’s westward-marching army camped at Ninety Six. At the small “stockade” fort there, Abraham found “a great number of miserable people, chiefly women and children, cooped up” within the palisaded walls. Captain Thomas Bell, the commander, was regarded as “a good sort of a man,” but his garrison consisted of a small, motley body of men drawn from the local refugee settlers, “for none else can be spared.” All the professional soldiers in the province had been drawn into the army and were now marching toward the Cherokee’s Lower Towns.

One anonymous soldier who was part of the large army camped briefly at Fort Ninety Six encountered Abraham there and heard stories about his recent adventures. That soldier’s letter to the newspaper in Charleston briefly mentions our hero directly, and captures a bit of the flavor of the gossip then circulating about the man who had just returned from both Fort Loudoun and Fort Prince George: “This negro [Abraham], who is [still] the property of one Mr. Behn [Benn], has certainly executed the commands of the government, in delivering the letters at both forts, with surprising dispatch, in the midst of so much danger.” Samuel Benn was still there at Ninety Six, having lost his business as a trader in the Overhill Cherokee town of Tanasi, but now he found work as a guide for Colonel Montgomery as the army pushed westward.[12]

Departing from Ninety-Six around May 24th or 25th, Abraham continued his journey on horseback towards Charleston. On May 31st, the South Carolina Gazette reported “The Negro Abram [Abraham], who belonged to Mr. Samuel Behn, and lately obtained his freedom, since his recovery from the small-pox, has delivered some dispatches from his Honour the Lieutenant Governor, at both forts in the Cherokees; and was at [the private fort at] Beaver Creek [about sixteen miles northwest of downtown Orangeburg], on his return, with answers to those dispatches, last Tuesday [May 27th], but is not yet come to [Charles] town. We hear that he was fired at [by Cherokee gunmen] 30 miles on this side of Ninety-Six, and obliged to alter his route.”[13] Abraham finally reached the gates of Charleston on the evening of Saturday, May 31st. After showing his credentials to the town’s military watchmen, he would have immediately delivered his official dispatches to Lt. Governor Bull (perhaps visiting his private residence at what is now No. 35 Meeting Street). Having completed his third long-distance mission, the fearless messenger settled into an unknown location for a well-deserved rest.

One week later, on June 7th, the South Carolina Gazette once again informed the people of Charleston that “last Saturday night the Negro Abram [Abraham] arrived in town with the dispatches he brought from Fort Loudoun and Fort Prince-George.” Acting on the intelligence he had delivered, the South Carolina government decided to send even more troops to fight the Cherokee. Most of the white men in the colony were now in arms, streaming westward and leaving the more densely-populated Lowcountry relatively unprotected. In order to allay the white fear of slave uprisings during this period of weakness, Lt. Gov. Bull decided to call up the Lowcountry militia. On the morning of June 7th, “an alarm was fired at Granville’s Bastion (two guns at a time at three minutes distance) and one half of the militia of the whole province draughted, to be ready to march on the first notice, with 14 days provisions, to the several places of rendezvous that are appointed, with trusty Negroes, good gun-men, agreeable to the Militia Act.”[14]

One week later, on June 7th, the South Carolina Gazette once again informed the people of Charleston that “last Saturday night the Negro Abram [Abraham] arrived in town with the dispatches he brought from Fort Loudoun and Fort Prince-George.” Acting on the intelligence he had delivered, the South Carolina government decided to send even more troops to fight the Cherokee. Most of the white men in the colony were now in arms, streaming westward and leaving the more densely-populated Lowcountry relatively unprotected. In order to allay the white fear of slave uprisings during this period of weakness, Lt. Gov. Bull decided to call up the Lowcountry militia. On the morning of June 7th, “an alarm was fired at Granville’s Bastion (two guns at a time at three minutes distance) and one half of the militia of the whole province draughted, to be ready to march on the first notice, with 14 days provisions, to the several places of rendezvous that are appointed, with trusty Negroes, good gun-men, agreeable to the Militia Act.”[14]

During this time of great agitation and alarm in South Carolina, Lieutenant Governor William Bull paused for a moment to reflect on Abraham’s valuable services to the province and to His Majesty’s government. On Thursday, June 12th, Bull wrote a brief but important letter to the Commons House of Assembly concerning the status of Abraham’s freedom from slavery. He handed the document to John Bassnett, the official messenger for His Majesty’s Council, who carried it to the State House at the northwest corner of Meeting and Broad Streets. There he handed the letter to Benjamin Smith, the Speaker of the Commons House of Assembly, who immediately read the lieutenant governor’s message aloud to the House:

“Mr. Speaker and Gentlemen, When the Cherokees broke out war with this Province [in January of 1760], Captain [Paul] Demeré of Fort Loudoun thinking it his duty to acquaint the governor with the approaching distress to which the fort and garrison under his command was likely to be reduced, after he had in vain attempted to acquaint the governor of Virginia, the two messengers sent by him, for that purpose, being taken and one killed, promised to a Negro, named Abram [Abraham], the property of Mr. Samuel Behn [or Benn], formerly an Indian trader, and now a guide in Colonel Montgomery’s army, to endeavour [sic] to obtain his freedom, as a reward, if he would undertake to carry letters from him to the governor of this province. In the execution of which he was to pass through the whole Cherokee Nation. This service he faithfully did perform. And, after having the small-pox in Charles Town, he, with great danger and fidelity, carried letters from me to Fort Prince George and Fort Loudoun, and returned with answers last week. Therefore, in order to excite others in his condition to undertake the like dangerous and necessary services, in hopes of the like great reward; I recommend the merits of the said Negro Abram to your consideration, and desire that you would provide a suitable [monetary] satisfaction to his master for his freedom accordingly.”

Having read aloud Lt. Gov. Bull’s message, House Speaker Benjamin Smith then ordered “that a committee be appointed to take the said message into consideration,” and assigned this duty to the following wealthy, slave-owning gentlemen: Thomas Lamboll, John Guerard, Henry Laurens, John McQueen, Charles Pinckney (1732–1782), and Thomas Wright. Before moving on to other matters, Speaker Smith ordered the committee members to “examine the matter of the said message and [, sometime later,] report the same with their opinion thereupon to the House.”[15]

Nearly five months after Capt. Demeré’s promise of freedom, the legislative process of securing and confirming Abraham’s freedom from slavery began in earnest on June 12th, 1760. Nothing in government moves quickly, however, so our hero would have to wait for quite some time before the committee of white gentlemen would take up their assignment and complete their simple task of considering the merit of Abraham’s case. In the meantime, he was not the type of man to sit idly in Charleston while his friends and associates in the Cherokee territory suffered starvation and fear. Emboldened by the legal progress towards his official manumission, Abraham set out on another dangerous express mission for Lt. Gov. Bull.

In our next installment of the story of Abraham the Unstoppable, we’ll follow our hero westward in late June of 1760, as he witnesses the devastating effects of the British army’s bloody and vengeful campaign through the Lower Towns of the Cherokee nation.

[1] Robert Wells, Wells’s Register: Together with an Almanack . . . for the Year of our Lord 1774 (Charleston, S.C.: Robert Wells, 1774), unnumbered pages, includes a list of 1770 population statistics.

[2] Suzanne Krebsbach, “The Great Charlestown Smallpox Epidemic of 1760,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 97 (January 1996): 37, says the epidemic was declared officially over in November.

[3] Lyttelton announced his departure to the Commons House on 11 March 1760. See Terry Lipscomb, ed. The Colonial Records of South Carolina: The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, October 6, 1757–January 24, 1761 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press for the South Carolina Department of Archives and History [SCDAH], 1996), 481–82 (available online from SCDAH). William Bull announced his assumption of the office of on 27 March. See the manuscript Journal of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, No. 28, p. 183, at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History. See also Lt. Governor Bull’s proclamation regarding the transition of power in South Carolina Gazette, 29 March–7 April 1760.

[4] For more information about the lieutenant governor, see Kinloch Bull, The Oligarchs in Colonial and Revolutionary Charleston: Lieutenant Governor William Bull II and His Family (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1991).

[5] For a detailed discussion of the massacre at Fort Prince George, see Daniel J. Tortora, Carolina in Crisis: Cherokees, Colonists, and Slaves in the American Southeast, 1756–1763 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 90–101.

[6] South Carolina Gazette, 29 March–7 April 1760; Fitzhugh McMaster, Soldiers and Uniforms: South Carolina Military Affairs, 1670–1775 (Columbia: South Carolina Tricentennial Commission, 1971), 60, 63.

[7] The extant journals of South Carolina Commons House of Assembly for this period include several accounts of treasury payments made “for expresses,” but such accounts generally do not specify the names of the messengers.

[8] Pennsylvania Gazette, 19 June 1760, quoting from a now-lost edition of the South Carolina Weekly Gazette, 14 May 1760.

[9] South Carolina Gazette, 24–31 May 1760.

[10] South Carolina Gazette, 31 May–7 June 1760.

[11] South Carolina Gazette, 31 May–7 June 1760.

[12] [Christopher Gadsden], Some Observations on the Two Campaigns against the Cherokee Indians, in 1760 and 1761. In a Second Letter from Philopatrios (Charleston, S.C.: Peter Timothy, 1762), 76, citing a letter dated “Camp at Ninety-Six, May 27,” printed in a now-lost edition of the South Carolina Weekly Gazette, 4 June 1760.

[13] South Carolina Gazette, 24–31 May 1760.

[14] South Carolina Gazette, 31 May–7 June 1760.

[15] Lipscomb, ed. Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, 1757–1761, 645.

PREVIOUS: Abraham the Unstoppable, Part 3

NEXT: The Unmarked Grave of Ellen O’Donovan Rossa

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments