The Carolina Coffee House of London

Processing Request

Processing Request

Thousands of prospective emigrants first learned about the Carolina Colony and booked passage to that distant land at a small coffee shop in the heart of London. From the 1670s to the 1830s, the Carolina Coffee House in Birchin Lane served as the epicenter for conversations about the colony, its business opportunities, and its residents. To better understand the important role of this long-forgotten coffee spot, we’ll take a tour through its caffeinated history and conclude with a virtual stroll through Birchin Lane.

The early history of the cultivation of coffee for human consumption is rooted in the mountains of Ethiopia, from which the practice spread eastward of that ancient African landscape. European crusaders of the Middle Ages may have encountered coffee culture among their Arabic foes in what we now call the Near East, but they apparently didn’t bring home an addiction to the black stuff when they returned. Coffee beans first came to England at some point in the first half of the seventeenth century with English merchants with Dutch connections who were trading in the East Indies (that is, Asia). The beans were initially regarded as something of a novelty with dubious commercial potential. The first establishment in England to retail coffee as a hot beverage appeared in Oxford in 1650, and by 1652 there was a coffee shop in the City of London. More specifically, the first coffee house in London was located in St. Michael’s Alley, just a few yards to the southeast of the Royal Exchange, in the ward known as Cornhill.

The location of the first London coffee house is significant. Cornhill isn’t just another picturesque neighborhood in that ancient city, it’s the epicenter of commerce within a city known as the capital of international business. From the opening in 1562 of the first Royal Exchange, facing Cornhill Street, that ward became known as the place to go to meet like-minded folks interested in trade, finance, and profit. The rise of joint-stock companies in the seventeenth century, like the Virginia Company, the East India Company, and the Royal African Company, drew more investors to Cornhill, and the creation of the Bank of England in 1694 solidified the ward’s reputation as a center for business. Even today in 2020, between Threadneedle Street on the north and Lombard Street on the south, you’ll find more international business transacted in Cornhill than in many sovereign nations combined.

Following the Restoration of the English monarchy in 1660, that nation experienced a strong resurgence of trade and investment. A new species of financial speculators and investors arose who sought to take advantage of England’s growing trade networks around the globe, but the use of fixed, formal offices was not yet a regular practice. Looking for places to meet clients and partners for conversation, the businessmen of Cornhill turned to the new-fangled coffee houses that were popping up throughout the neighborhood. In contrast to ye olde fashioned taverns and ale houses that served beer, wine, and spirituous liquors to a diverse, often rowdy clientele, the coffee houses and coffee rooms of post-Restoration London catered to a more affluent customer looking for a more refined, business-friendly environment.

Following the Restoration of the English monarchy in 1660, that nation experienced a strong resurgence of trade and investment. A new species of financial speculators and investors arose who sought to take advantage of England’s growing trade networks around the globe, but the use of fixed, formal offices was not yet a regular practice. Looking for places to meet clients and partners for conversation, the businessmen of Cornhill turned to the new-fangled coffee houses that were popping up throughout the neighborhood. In contrast to ye olde fashioned taverns and ale houses that served beer, wine, and spirituous liquors to a diverse, often rowdy clientele, the coffee houses and coffee rooms of post-Restoration London catered to a more affluent customer looking for a more refined, business-friendly environment.

Coffee was the fashionable beverage du jour for English gentlemen of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, but coffee houses served a variety of stronger drinks as well. Besides the potent black stuff, these novel establishments offered another new and highly addictive commodity for which businessmen clamored: news. The proprietors of various Cornhill coffee houses, often called “coffeemen,” strove to acquire, collect, and share news of all sorts with their customers, who could then make business decisions based on the information at hand. If, for example, one knew that a hurricane had recently damaged the sugarcane crop in far-away Jamaica, one could reasonably predict that the price of sugar at the nearby Royal Exchange would soon increase, and then make or recommend investments accordingly. The advent of regular, printed newspapers was a direct outgrowth of this sort of commodification of information that began as a practical marketing tool in the coffee houses of late seventeenth century Cornhill.

The availability of news or “advices” from all over England, continental Europe, and the far-flung colonies drew men of commerce as well as educated men in general (sorry, ladies, but early coffee houses were not receptive to the presence of intelligent women). Discussions of politics, philosophy, art, music, and other erudite topics also enlivened many a coffee house, especially during their heyday in the eighteenth century. Some coffee houses even charged a penny for admission, a practice that inspired more than one writer to describe them as “penny universities.” From these dens of casual business and rarified banter emerged such cultural phenomena as the Royal Society, Freemasonry, Lloyd’s List, building insurance schemes, public museums, concert societies, periodic magazines, and the Carolina Colony.

To be clear, I know of no evidence suggesting that the creation of the Carolina Colony in 1663 was directly related to a series of conversations that took place in a London coffee house. Considering the fashion for coffee houses at that time, and considering the social life of the men who were responsible for creating Carolina, however, it would surprise me if at least some of the business conversations that led to the Carolina Charter of 1663 did not take place at one of the scores of coffee houses in the city. The eight Lords Proprietors to whom King Charles II granted Carolina were wealthy, well-connected men with a variety of business interests, but none of them ever visited their colonial possession. Instead, they associated and contracted with other Englishmen who promoted the colony as an investment opportunity and sought to recruit volunteers to travel abroad to settle the land. These subsequent but very necessary conversations must have taken place at coffee houses in the shadow of the Royal Exchange in Cornhill.

The great London fire of September 1666 decimated Cornhill, in the heart of the old city, but the nation’s financial sector was quickly rebuilt. A new Royal Exchange building opened in 1669, and new coffee houses reappeared like mushrooms throughout the neighborhood. Despite anti-coffee propaganda that described the dark brew as a “Ninny broth” that allegedly destroyed a man’s sexual virility, the beverage’s popularity continued to grow and spread throughout the island nation. The fledging English postal service co-opted the proliferation of coffee houses by using them as depots for the collection and distribution of mail. By the turn of the eighteenth century, there were many hundreds of coffee houses spread across the City of London, with a significant concentration near the Royal Exchange in Cornhill.

Within this urban landscape of coffee and conversation arose a number of establishments catering to specific business interests. Gentlemen interested in investing in or traveling to the colony of Virginia, for example, could visit the Virginia Coffee House in Cornhill and speak with agents and travelers who had first-hand knowledge of that place. If you needed to send a message to an associate in Jamaica, you went to the Jamaica Coffee House in St. Michael’s Alley and dropped a letter in the mail bag, which would travel outbound with the next ship departing for that island. If you were waiting to hear news of your cousin visiting the Holy Land, you turned a few steps to the east and made inquiries at the Jerusalem Coffee House. If you wanted to wag your finger in a scolding fashion at men investing in the slave trade, you turned back to St. Michael’s Alley into the African Coffee House. In short, Cornhill once hosted scores of coffee outlets that specialized in connecting English investors and families with business concerns and emigrants spread around the world.

Within this urban landscape of coffee and conversation arose a number of establishments catering to specific business interests. Gentlemen interested in investing in or traveling to the colony of Virginia, for example, could visit the Virginia Coffee House in Cornhill and speak with agents and travelers who had first-hand knowledge of that place. If you needed to send a message to an associate in Jamaica, you went to the Jamaica Coffee House in St. Michael’s Alley and dropped a letter in the mail bag, which would travel outbound with the next ship departing for that island. If you were waiting to hear news of your cousin visiting the Holy Land, you turned a few steps to the east and made inquiries at the Jerusalem Coffee House. If you wanted to wag your finger in a scolding fashion at men investing in the slave trade, you turned back to St. Michael’s Alley into the African Coffee House. In short, Cornhill once hosted scores of coffee outlets that specialized in connecting English investors and families with business concerns and emigrants spread around the world.

Among the numerous geo-specific dens of caffeine was, of course, the Carolina Coffee House, which stood approximately two hundred feet southeast of the Royal Exchange. It was situated on the east side of a narrow footpath called Birchin Lane, just four doors south of Cornhill Street. We don’t know precisely when the Carolina Coffee House served its first cup of joe, but documentary evidence shows that it was in operation before 1682. London didn’t have a street address numbering system until the late 1760s, at which point the Carolina Coffee House was designated No. 25 Birchin Lane. Published directories of the English capital demonstrate that it remained at this location until at least 1831.[1]

From time to time during its century and a half of operation, London’s Carolina Coffee House also shared space with the representatives of other colonial centers. Business directories from eighteenth-century London show that its name was occasionally expanded to the Carolina and Pennsylvania Coffee House, or the Pennsylvania, Carolina, and Georgia Coffee House, or the Amsterdam, Carolina, Pennsylvania & Pensacola Coffee House, or the Carolina and Honduras Coffee House. Regardless of who else was sharing the tables during its long tenure, businessmen, investors, travelers, and relatives could always visit this Birchin Lane fixture to find a direct line of communication with Charleston.[2]

To my knowledge, the earliest reference to the Carolina Coffee House appears in a pamphlet published in the Cornhill ward of London in 1682 by Samuel Wilson, titled An Account of the Province of Carolina in America. In the conclusion of that promotional work, the author invited anyone interested in learning more about the colony to ask for further information: “Some of the Lords Proprietors or myself will be every Tuesday [at] eleven of the clock at the Carolina Coffee House in Burching [sic] Lane near the Royal Exchange[,] to inform all people what ships are going, or any other things whatever.”[3]

We have very little surviving information about the proprietors of the Carolina Coffee House, or the identity of the waiters and baristas, but, curiously, a few names have survived in records on both sides of the Atlantic. Late in the year 1699, for example, “Edward Crisp of London[,] Coffeeman,” appointed Thomas Pinckney and Christopher Smith, both Carolina merchants, to act as his attorneys in recovering a debt from Charles Odinsell in Charleston.[4] In a court deposition filed in the spring of 1721, Edward Crisp identified himself as a “coffeeman” at the Carolina Coffee House in Birchin Lane, where he regularly witnessed some of the Lords Proprietors interacting with businessmen and others traveling to and from the Carolina Colony in the early eighteenth century.[5]

We have very little surviving information about the proprietors of the Carolina Coffee House, or the identity of the waiters and baristas, but, curiously, a few names have survived in records on both sides of the Atlantic. Late in the year 1699, for example, “Edward Crisp of London[,] Coffeeman,” appointed Thomas Pinckney and Christopher Smith, both Carolina merchants, to act as his attorneys in recovering a debt from Charles Odinsell in Charleston.[4] In a court deposition filed in the spring of 1721, Edward Crisp identified himself as a “coffeeman” at the Carolina Coffee House in Birchin Lane, where he regularly witnessed some of the Lords Proprietors interacting with businessmen and others traveling to and from the Carolina Colony in the early eighteenth century.[5]

Whether Edward Crisp was the proprietor of the Carolina Coffee House between the late 1690s and the early 1720s, or whether he was simply a barista who prepared bowls of java for drowsy customers, is still an unresolved matter. Nevertheless, we can be sure that he was neither a cartographer, an engraver, nor a commercial publisher. Here, I’m alluding to a well-known map published in London in the year 1711 that I and many other historians often refer to as the “Crisp Map.” More formally known as A Complete Description of the Province of Carolina in 3 Parts, this map includes a detailed view of the South Carolina coastline, a bit of the Gulf of Mexico, and an inset showing the fortified environs of urban Charleston.[6] The map’s long title concludes with the phrase “published by Edw. Crisp,” but it includes no further information to clarify his role in the map’s creation. It seems unlikely that this coffeeman ever visited Carolina, so he was probably responsible for coordinating the effort to combine several different maps, created by different artists at different times, into one large printed sheet.

By turning to the surviving records of the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, we find a sort of confirmation of Edward Crisp’s role in creating this familiar map. In June of 1711, the Proprietors ordered their secretary to pay ten guineas to Mr. Edward Crisp “for a map of Carolina and a draught of Port Royal,” and to set aside six hundred acres of land in the colony for the industrious coffeeman. The proprietors described these rewards to Crisp as an acknowledgement of the “several proofs of his good inclinations to our service and his earnest endeavours to promote the general good of our province.”[7]

Surviving letters written by a number of eighteenth-century Charlestonians confirm the central role of the Carolina Coffee House in connecting the great metropolis with the distant colony. In a letter written in November 1714, for example, the Rev. Gideon Johnston informed his London friends that the new brick church in Charleston (St. Philip’s Church), then under construction, had been damaged by a hurricane that struck South Carolina two months earlier. Johnston was in London at the time, however, so he did not personally experience that storm. Rather, he had received a letter from William Rhett of Charleston that provided many details. “Last Tuesday att the Carolina Coffee house,” Johnston said, he learned “that had not the wind chopt about suddenly & att that nick of time, Charlestown w[i]t[h] all its inhabitants had been laid under watter.”[8]

South Carolina businessman Henry Laurens spent many hours at the Carolina Coffee House during his several sojourns to London between the 1740s and the 1770s, and his surviving letterbooks contain numerous references to sending and receiving mail through that venerable establishment.[9] Similarly, twenty-two-year-old Peter Manigault (1731–1773) was studying law in London when he wrote to his mother in December 1753. Peter assured her that he did not waste time and money as many of his Carolina peers did in London. The other young bucks teased him, said the young Mr. Manigault, because “I refused to sit with [them] in the pit at the play-house, to have tobacco spit upon me out of the one-shilling gallery, but chose to go into the boxes, because that is the proper place for a gentleman to be seen in,” and because “I do not lounge away my mornings at that most elegant place the Carolina Coffee House, in Birchin Lane.”[10]

South Carolina businessman Henry Laurens spent many hours at the Carolina Coffee House during his several sojourns to London between the 1740s and the 1770s, and his surviving letterbooks contain numerous references to sending and receiving mail through that venerable establishment.[9] Similarly, twenty-two-year-old Peter Manigault (1731–1773) was studying law in London when he wrote to his mother in December 1753. Peter assured her that he did not waste time and money as many of his Carolina peers did in London. The other young bucks teased him, said the young Mr. Manigault, because “I refused to sit with [them] in the pit at the play-house, to have tobacco spit upon me out of the one-shilling gallery, but chose to go into the boxes, because that is the proper place for a gentleman to be seen in,” and because “I do not lounge away my mornings at that most elegant place the Carolina Coffee House, in Birchin Lane.”[10]

South Carolinians visiting London were not the only ones familiar with the Carolina Coffee House. The early newspapers of colonial-era Charleston demonstrate that its utility and fame crossed the pond to these shores as well. Mr. Bernard Marrett, for example, a man who at some point in the 1720s acted as proprietor or manager of the Carolina Coffee House in Birchin Lane, quit that establishment and settled in Charleston in the early 1730s. We don’t know how long Mr. Marrett resided in the Palmetto City, but it appears that life in the provincial capital did not agree with the coffeeman. On the 20th of May 1732, Bernard Marrett put a rope around his neck and took his own life. “The next day,” reported the South Carolina Gazette, “the Coroner’s Inquest sat upon him [that is, convened to view his body], and brought in the verdict of Non compos Mentis” (not in his right mind).[11]

Similarly, in May of 1763, the South Carolina Gazette reported the death of Mary Taylor, who was the wife of John Taylor, the man “who kept the Pennsylvania, Carolina, and Georgia Coffee House in Birchin-Lane, London.”[12] On a more cheerful note, I’ll mention that a man calling himself simply “Bob” placed a curious advertisement in the local newspapers of 1772. Identifying himself as a “waiter from the Carolina and Pennsylvania Coffee House, Birchin Lane,” Bob notified his potential customers in Charleston that “he has taken Cole’s and the Greenland Coffee-House, in Ball-Court, Cornhill; which he has fitted up very elegantly, and assures all Gentlemen that favour him with their Commands, he will exert his utmost Endeavours to merit their Favours: And for the Accommodation of American Gentlemen, the South-Carolina, Georgia, and Pennsylvania News-Papers, will be regularly taken in.” Bob concluded his business notice with a final word designed to tempt his colonial customers: “He makes American Punch in Perfection.”[13]

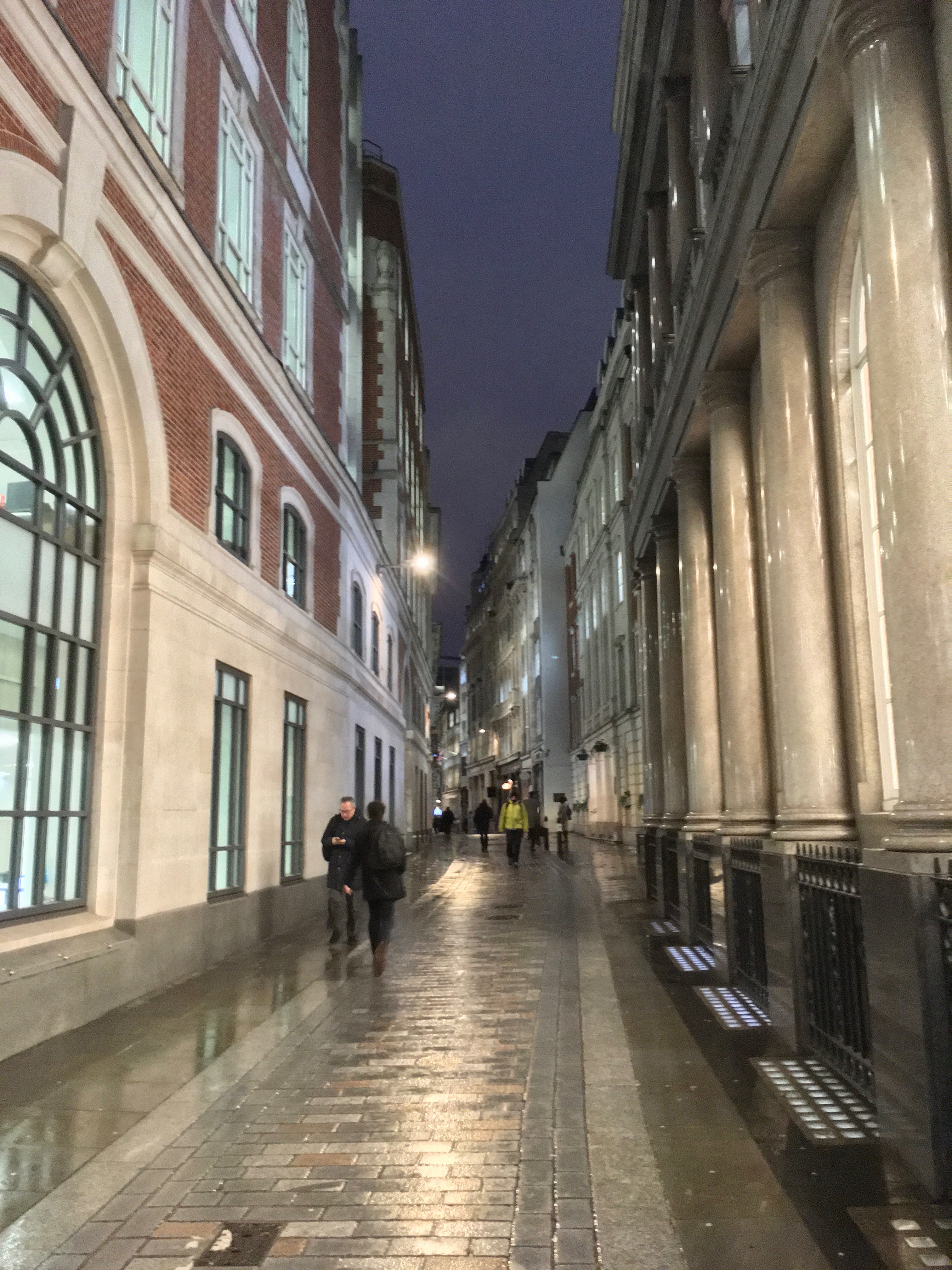

Having studied early South Carolina history for more than twenty years, I had read all of this information about the Carolina Coffee House in books, newspapers, and manuscripts, but I had never personally traveled to London to experience the physical context of this important part of our community’s story. I recently had a chance to amend that score, however, when I embarked a research trip to England earlier this month. Much of that trip was spent at the National Archives of the United Kingdom, adjacent to Kew Gardens, but that institution is closed on Mondays. So on the afternoon of Monday, January 6th, I wandered from my hotel in Trafalgar Square, up the Strand to Fleet Street, then into Ludgate Hill, through St. Paul’s Cathedral into Cheapside, to the Royal Exchange in Cornhill. From that point, finding Birchin Lane was a piece of cake. You just continue eastward, cross to the south side of the street, and enter the ancient narrow footpath.

The old Carolina Coffee House, once located four doors south of Cornhill Street on the left side of the lane, no longer exists. The original building perished a 1748 fire that also consumed the original Royal Exchange and a significant portion of the surrounding neighborhood. The old coffee houses were rebuilt immediately after that fire, but the Carolina Coffee House closed sometime before the American Civil War. Birchin Lane, which is just a bit wider than Charleston's Philadelphia Alley, is now crowded by modern buildings and paved with handsome bricks. No physical trace of the Carolina Coffee House survives, nor is there a marker to memorialize its former location. Nevertheless, my passion for Charleston history compelled me to make a sort of pilgrimage to the site that was once so important to our state’s history.

The old Carolina Coffee House, once located four doors south of Cornhill Street on the left side of the lane, no longer exists. The original building perished a 1748 fire that also consumed the original Royal Exchange and a significant portion of the surrounding neighborhood. The old coffee houses were rebuilt immediately after that fire, but the Carolina Coffee House closed sometime before the American Civil War. Birchin Lane, which is just a bit wider than Charleston's Philadelphia Alley, is now crowded by modern buildings and paved with handsome bricks. No physical trace of the Carolina Coffee House survives, nor is there a marker to memorialize its former location. Nevertheless, my passion for Charleston history compelled me to make a sort of pilgrimage to the site that was once so important to our state’s history.

In the winter darkness that one experiences at 4:45 on a January afternoon in England, I stood quietly in Birchin Lane and imagined all those who had passed this way on their journey to Carolina. The bright lights shining through the cold, misting rain created an enigmatic aura that heightened the experience. This spot was, in some ways, the “ground zero” of Carolina. It was the touchstone for thousands of travelers sailing to and from that distant land, from the beginning of the colonial experiment to its break from English rule and beyond. Stretching around 350 feet between Cornhill Street southward to Lombard Street, Birchin Lane was for me at that moment a sort of time machine that helped me understand some of facts that I had learned in dusty old books and papers. Being there, as they say, really makes a difference.

At five p.m., I stepped out from the south end of Birchin Lane and headed northwest on Lombard Street towards the Bank of England. A word of warning for any Carolinians visiting this spot at a similar time of day. It’s as if alarm sounds in every financial office throughout Cornhill—the modern center of international banking—precisely at 5 p.m., and tens of thousands of business folk fly from their desks and into the streets. Having just spent a few minutes in a revelry of historical bliss, I suddenly felt like a salmon swimming upstream through an obstacle course of hungry bears. It wasn’t necessarily an unpleasant experience, but it was certainly a jolt back to the reality of modern-day London. Make a note of that phenomenon when you make your own pilgrimage to Birchin Lane.

In the meantime, I’ll see you at the coffee house.

In the meantime, I’ll see you at the coffee house.

Suggestions For Further Reading:

Cowan, Brian. The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2005.

Ellis, Aytoun. The Penny Universities: A History of the Coffee-Houses. London: Secker & Warburg, 1956.

Lillywhite, Bryant. London Coffee Houses: A Reference Book of Coffee Houses of the Seventeenth Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1963.

Markman, Ellis, ed. Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Wild, Antony. Coffee: A Dark History. New York: Norton, 2004.

[1] James Elmes, A Topographical Dictionary of London and Its Environs (London: Whittaker, Treacher and Arnot, 1831), 103, gives the address of the Carolina Coffee House as “No. 25, Birchin-lane, four houses on the left from Cornhill.”

[2] For a discussion of the permutations of names, See Bryant Lillywhite, London Coffee Houses: A Reference Book of Coffee Houses of the Seventeenth Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries (London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1963), 147–49.

[3] You can see the title page of Wilson’s 1682 pamphlet on the website of Newcastle University, and read the entire digitized text on the website of Early English Books, or in Bartholomew Rivers Carroll, Historical Collections of South Carolina, volume 2 (New York, Harper & Brothers, 1836), 19–35.

[4] Caroline T. Moore, ed., Abstracts of Records of the Secretary of the Province of South Carolina, 1692–1721 (by the author, 1978; reprinted, Columbia, S.C.: SCMAR, 2003), 197–98.

[5] Charles H. Lesser, South Carolina Begins: The Records of a Proprietary Colony, 1663–1721 (Columbia: South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1995), 44.

[6] You can view and download an extremely high-resolution digital copy of this map on the website of the Library of Congress.

[7] BPRO transcripts, 6: 47; “List and Abstract of Documents Relating to South-Carolina, Now Existing in the State Paper Office, London,” in Collections of the South Carolina Historical Society, volume 1 (Charleston, S.C.: South Carolina Historical Society, 1857), 183. On 1 June 1716, the Register of South Carolina recorded a grant to Edward Crisp of 500 acres in Berkeley County, South Carolina, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Colonial Land Grants (copy series), volume 39, page 185. Crisp later conveyed this property to other parties in South Carolina, and apparently never visited the colony himself.

[8] Frank J. Klingberg, ed., Carolina Chronicle: The Papers of Commissary Gideon Johnston, 1707–1716 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1946), 143–44, citing a letter from Johnston dated 19 November 1714. In an editorial note introducing this letter, Klingberg incorrectly conflates the hurricanes of 5–6 September 1713 and 10 September 1714 (Julian Calendar).

[9] See, for example, Joseph W. Barnwell, ed., “Correspondence of Henry Laurens,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 31 (January 1930): 26.

[10] Mabel L. Webber, ed., “Peter Manigault’s Letters,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 32 (October 1931), 271. The original letter is part of the Manigault Family Papers at the South Carolina Historical Society.

[11] South Carolina Gazette, 20–27 May 1732 (Saturday).

[12] South Carolina Gazette, 14–21 May 1763.

[13] South Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, 18 August 1772.

PREVIOUS: The Myth of the Holy City

NEXT: Defining Charleston’s Free People of Color

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments