The Charleston Baseball Riots of 1869, Part 2

Processing Request

Processing Request

Reeling from embarrassment after rioting spoiled an afternoon of baseball on Citadel Green, the divided people of Charleston anxiously prepared for a rematch against the Savannah Base Ball Club in August of 1869. The mayor’s show of force inflamed simmering tensions, however, and boiling frustration led to gunfire while the people hoped in vain for a quiet weekend of relaxing sport.

Newspaper reports of the Charleston baseball riots of July 26th, 1869, spread across the country, accompanied by editorials that lamented the inability of Charleston’s municipal government to suppress the violence. The city’s urban population numbered nearly 50,000 people, half of whom were of African descent, but white voices espousing a racially biased perspective dominated the local press. Charleston’s white Republican mayor, Gilbert Pillsbury, however, was determined to show that he was neither weak nor “powerless.” A few days after the rioting, he secured from an army depot in Columbia a cache of 125 Winchester repeating rifles with bayonets to re-arm the city’s police force for the first time since the end of the recent war. If any white citizens harbored any doubt of his ability to maintain civil order, he was prepared to give them a graphic demonstration.

Meanwhile, the leaders of the Carolina Base Ball Club of Charleston steamed down to Savannah to plead with the ball team to return to Charleston. Their recent game was the first in a planned series of three, and the second game was supposed to take place in the Forest City. When asked to move the next game to the Palmetto City, the Savannah club declined. They didn’t blame the late riot on the Charleston sportsmen, but the Georgia team did want to enjoy the home-field advantage for the second game. Besides, traveling away from home and work for several days was expensive. The Carolina agents felt a deep sense of shame for the recent unrest, however, and continued to plead their case. They asked the Savannah “nine” to return to Charleston, not simply for the benefit of the baseball team, but for the honor of the entire community in Charleston. The riotous behavior of an unruly minority had embarrassed the whole city, and a rematch between the two teams in Charleston, said the Carolina club, would help dispel the stigma of racial unrest in the eyes of the nation.

With great reluctance and bit of sympathy, the Savannah team finally consented to return to Charleston. The Carolina Club proposed that they should return on Saturday, August 7th, for a match game on Monday the 9th. The Savannah club refused to play so soon, however, because they wanted to bring the Washington Cornet Band with them. The “wounded members” of that African-American brass band “had not fully recovered, nor had their ruined instruments been replaced.” To allow a bit more time for the band to heal and get their equipment in order, the two teams agreed to play their second game on Monday, August 16th.

Back in Charleston, the amateur members of the Carolina Base Ball club were making an effort to practice more diligently and to improve their team spirit. The Savannah club had displayed more coordination and strategy during the previous game, and news from the south suggested the Georgia “boys’ were now practicing every day to return in even better form.[1] To help focus their efforts, the Charleston club stopped using Citadel Green as a ball field and staked out a rectangular space measuring six hundred feet by four hundred feet somewhere near the west end of Broad Street (before Colonial Lake was officially created). This temporary ball field, delineated by wooden stakes surmounted by a continuous rope fence, was really a reclaimed mudflat that the city was gradually filling with garbage to facilitate future suburban development. For the immediate purpose, however, the city’s street department topped the muddy surface with a layer of clay and leveled it by using a team of mules dragging a heavy beam behind them.[2]

Back in Charleston, the amateur members of the Carolina Base Ball club were making an effort to practice more diligently and to improve their team spirit. The Savannah club had displayed more coordination and strategy during the previous game, and news from the south suggested the Georgia “boys’ were now practicing every day to return in even better form.[1] To help focus their efforts, the Charleston club stopped using Citadel Green as a ball field and staked out a rectangular space measuring six hundred feet by four hundred feet somewhere near the west end of Broad Street (before Colonial Lake was officially created). This temporary ball field, delineated by wooden stakes surmounted by a continuous rope fence, was really a reclaimed mudflat that the city was gradually filling with garbage to facilitate future suburban development. For the immediate purpose, however, the city’s street department topped the muddy surface with a layer of clay and leveled it by using a team of mules dragging a heavy beam behind them.[2]

On the afternoon of Friday, August 13th, Mayor Pillsbury summoned to City Hall the president of the Carolina Base Ball Club, twenty-two-year-old cotton-presser Benjamin Franklin McCabe. The mayor had heard rumors that the members of the Carolina club intended to provide a large armed escort for the Savannah team when they arrived. This plan, he said, might clash with the duties of the newly-armed Charleston Police Department, and he was anxious to prevent any sort of disturbance. Mr. McCabe replied he was not familiar with any plans for an armed escort or procession, and the members of his club would not take any actions that might endanger the peace of the city. On the other hand, said the young baseball president, the members of the Carolina Club were not responsible for any statements or plans relating to an armed guard that might be made by private individuals or members of the local press. The mayor seemed satisfied with this response, and let the matter drop.

Mr. McCabe told the mayor he was expecting to see quite a large crowd at the baseball game on Monday afternoon, and suggested that the city should temporarily close the streets near the baseball field. Mayor Pillsbury agreed, and informed the club president that he intended to send a large police force the ball field anyway. On Monday afternoon, therefore, those men would close the adjacent streets, except Tradd Street, to vehicular traffic. Speaking of traffic, the mayor also noted that several of the city’s new National Guard companies, composed of African-American men, were scheduled to parade on Monday the 16th, but he and other authorities had asked them to postpone their activities. With these precautions in place, both the sportsmen and the municipal government felt they had done their due diligence, and riotous demonstrations were neither feared nor expected.[3]

On Saturday morning, August 14th, however, the precarious peace in Charleston was shaken by a provocative editorial published in the Charleston Daily News. In an article seemingly designed to encourage a racial confrontation, the editor chastised the “powerless” character of the “weak and vacillating” mayor who had failed his white constituents three weeks earlier. It was now a matter of “honor and interest,” said the News, “of duty and of decency” for the white citizens of Charleston to become “exclusively responsible” for the protection of the visiting baseball club. “The white people of this city are in no mood to endure” the threats of “certain turbulent negroes among us,” said the newspaper, and they would not “again brook injury or insult, come whence it may.”[4] Everyone who read these words, including black Republicans praying for peace, recognized this editorial as a call to arms for vigilante muscle. By Saturday afternoon, the city was practically vibrating with nervous tension as the people awaited the arrival of the Savannah baseballers and their black brass band.

The Reception at the Wharf:

The Savannah “boys” left home on the steamboat Dictator at 10 a.m. on Saturday, August 14th. More than seven hours later, just after 5 p.m., they steamed up to South Atlantic Wharf along the Cooper River waterfront, just a bit north of the Old Exchange Building. There they were greeted by the shouts and cheers of their hosts—the Carolina Base Ball Club of Charleston—and more than a thousand white men who had assembled on the wharf. A newspaper reporter at the scene opined that the crowd was “the largest that has been witnessed in Charleston since the war, and was composed of the most respectable and influential [white] citizens.” Here there were no formal speeches or ceremonies, no concerted plan of action or grand expressions of power.

As the members of the Carolina club rushed onboard the steamer to greet their friends and to help them with their baggage, the members of the Washington Cornet Band stepped ashore and unpacked their instruments. The musicians had all recovered from the indignities and injuries sustained on July 26th, but they had not yet replaced their damaged horns. “They brought with them the same instruments that they used on the previous trip,” said a news report, “as the many indentations on them, received during the disgraceful riot, conclusively proved.”

While the guests were off-loading their baggage and preparing to disembark, the heavy rhythmic beat of marching men arrested everyone’s attention. Police chief Richard Hendricks marched from East Bay Street onto the crowded wharf with a squad of about forty uniformed men and two lieutenants, all armed with their new Winchester “16 shooter” rifles and fixed bayonets, and halted in front of the steamboat. The members of the two baseball teams immediately protested, stating that there was no danger of a disturbance at this place, and therefore there was no call for the presence of an armed patrol. The policemen remained motionless, immune to the civilian shouting. The leaders of the local baseball club decided to send a committee for an impromptu conference with Captain Hendricks.

There commenced a spirited semantic debate, the topic of which shaped the ensuing events. The sportsmen asked Captain Hendricks why he brought an armed squad to intrude on what was a peaceful civilian reunion. The police chief replied that the mayor and City Council had instructed him and his men “to come down to the wharf and protect the visitors from any potential insult.” The committee of baseballers pointed out that there was no disturbance at the wharf, nor was there any visible threat of insult or unrest. The home team was simply preparing to escort the visiting team to their hotel, and there was no need for a strong police presence. Captain Hendricks replied that if there was “a procession of citizens to escort them [the players],” he was under orders from the Mayor “to form his police in such a way as to make them [the police] the escort [for the citizens’ escort], and to do everything that could be done to prevent any disturbance, and to check at once any movement that tended to provoke them.”

The baseballers assured the police chief “that there would be no procession of the citizens.” All they intended was to form a marching “line” of men composed of the two baseball teams and headed by the Washington Cornet Band, which “line” would “proceed quietly through the streets to the Charleston Hotel.” In their opinion, this intended “line” would not constitute a “procession.” Whatever the one-thousand-or-so private citizens in attendance chose to do was, however, none of their business. Captain Hendricks then angrily terminated the conference, complaining that the “‘whole affair’ was caused by the editorial in The News of that morning” that had effectively summoned a vigilante mob of white men. Hendricks curtly ended the conversation by affirming that “he had received his instructions and intended to carry them out.”

The chief’s statement “flew like wildfire” through the assembled crowd, “and created great excitement.” The Savannah sportsmen declared “that they would not go under the escort of the guard if it could be avoided.” If there was a riot, “they were satisfied that the Carolina club could protect them.” One prominent member of the local club suggested that they might appeal to the mayor to “remove the police,” but the crowd rejected the idea of negotiating with the mayor they despised. Another committee was sent to parley with Captain Hendricks, and once again they debated the precise definition of the term “procession.” The police chief repeated that he “had orders to have nothing to do with the affair so long as there was no procession of the citizens; if the clubs and the band marched up in line, he would not interfere.” If, however, “the citizens attempted to escort the clubs,” then he was under orders to form his armed police force into an escort for that citizens’ escort.

The March from the Wharf:

The committee of baseballers decided that there was no further need for concern, as they simply intended to form a “line” and march to the hotel. Having landed all their baggage and their musicians, the members of the two baseball clubs fell into line behind the Washington Cornet Band. As soon as the drummer commenced to beat the cadence of the step, however, the large crowd of white men in attendance, “without a concert of action or organization,” also stepped into motion and began to march in company with the ball players and the band. In short, the intended “line” had suddenly become a “procession” in the eyes of the law, though not in the eyes of those processing.

The committee of baseballers decided that there was no further need for concern, as they simply intended to form a “line” and march to the hotel. Having landed all their baggage and their musicians, the members of the two baseball clubs fell into line behind the Washington Cornet Band. As soon as the drummer commenced to beat the cadence of the step, however, the large crowd of white men in attendance, “without a concert of action or organization,” also stepped into motion and began to march in company with the ball players and the band. In short, the intended “line” had suddenly become a “procession” in the eyes of the law, though not in the eyes of those processing.

“As the line reached the gate of the wharf, a small squad of policemen filed out from the side, and placing themselves in front of the band, proceeded on the line of march.” The sportsmen and their band immediately halted, and demanded to know why the police were trying to escort their “line.” Chief Hendricks replied that he saw a procession, and was simply following his orders. “After some deliberation,” the baseballers determined to continue their march. As their “line” reached East Bay Street and turned south toward Broad Street, however, the policemen fell into formation along either side of the line and marched along in command of the procession. The sportsmen immediately shouted for a halt, and the entire motely procession stopped in its tracks. After some discussion among the baseballers, the club members refused to go any farther with the unwanted armed escort. The command “right about” was shouted, and the clubmen and musicians reversed direction in unison. With the band bringing up the rear, they all marched back to South Atlantic Wharf while the police remained motionless in the middle of East Bay Street.

“Re-arriving on the wharf, an informal indignation meeting was held.” The sportsmen debated several different strategies, each predicated on the desire to reach the Charleston Hotel without the assistance of an armed police escort. While this spirited meeting was underway, someone noticed that the police force had disappeared from view. In their absence, the pressure to form an alternate plan evaporated, and the sportsmen decided follow their original design. The two baseball clubs formed a “line” behind their band, and the assemblage of approximately twelve hundred white citizens formed at the front and the rear of their “line.” As the band played a march, the massive “procession” traversed southward across the wharves to the south side of the Old Exchange, then west into East Bay Street, and turned onto the sidewalk on the south side of Broad Street.

As the head of this crowd neared State Street, Captain Hendricks and his squad of forty-odd policemen suddenly reappeared from East Bay Street and sprinted diagonally across Broad Street. They charged into the procession with their rifles and bayonets and created a gap between the citizens and the band. The line halted and shouts of indignation rang out. Surrounded by angry citizens, the police chief firmly stated that he had seen a “procession” on the move, and he was simply following his orders to the letter. While the crowd vented their fury, Captain Hendricks ordered his men to “charge bayonets.” The policemen lowered their weapons and marched in formation towards the south sidewalk of Broad Street, forcing the citizens against the adjacent storefronts. As the crowd recoiled from the advancing bayonets, a policeman reportedly struck a citizen, who responded by grabbing the officer’s Winchester rifle and trying to wrench it from his hands.

At this point, reported the Charleston Daily News, “a scene of the wildest excitement ensued, and but for the feeling in the breast of every respectable citizen that there must not be, for any reason, a collision between the citizens and the police, there would have begun on the spot the bloodiest conflict which Charleston had ever known.” The scene in Broad Street, said the newspaper, “beggared description. The police were standing on the defensive; their officers were shouting themselves hoarse; the crowd was surging backwards and forwards—all having a look of uncertainty—each face asking the question, ‘what is to be done next?’”

Captain Hendricks was surrounded by a large, frothing crowd of angry citizens. The police chief asserted that the had no discretionary powers, but was obliged to obey his orders firmly. He offered to compromise by marching his men along one side of the street and to allow the procession to march along the other side, “but no one was willing to assent to this.” The leaders of the local baseball club, joined by several prominent citizens, now formed a committee to seek an audience with the mayor and to ask him to withdraw the police. After a bit of fruitless searching, the committee learned that the mayor was at City Hall, at the northeast corner of Meeting and Broad Streets, as if he had been waiting for trouble to erupt. In fact, the mayor had already summoned approximately one hundred U.S. Army soldiers, who were now standing guard in front of the building.

At approximately 7 p.m. on this Saturday evening, the committee of baseball enthusiasts climbed the marble steps of Charleston’s City Hall and found Mayor Pillsbury, accompanied by the white and black Republican members of City Council and state representatives Robert DeLarge and Alonzo Ransier, seated inside the Council Chamber. After a brief and testy verbal exchange, the mayor reluctantly consented to a compromise and ordered that Police Captain Hendricks should have “discretionary powers” to execute his duty as he saw fit.

The mayor and Mr. McCabe then proceeded to debate “the definition of the word procession.” McCabe argued that the large number of people accompanying the baseball clubs were merely well-wishing, respectable citizens. “There was no danger of a disturbance, and there is no necessity for the escort of policemen.” Mayor Pillsbury countered that he, as the city executive, was “the best judge of the danger,” and that “the whole affair seems to be a mob.” When McCabe replied firmly that “neither he nor any other members of the clubs desired to go under the escort of the mayor’s minions,” Councilman Thomas Jefferson Mackey shouted for his arrest. “The mayor then jumped up and ordered Mr. McCabe to leave the room.” While armed black policemen came trotting across the street to take him into custody, McCabe and his committee flew out of City Hall and returned to their comrades at the east end of Broad Street.

At this point, it was nearly 8 p.m., and the crowd of indignant white citizens had swelled to at least two thousand people. McCabe and the other members of the ad hoc committee described their interview with the mayor to the crowd and to Captain Hendricks. The police chief then exercised his “discretionary powers” by offering the same plan suggested earlier; that is, to keep his officers and the detachment of U.S. soldiers on the north side of Broad Street while the baseball clubs and citizens marched along the south side. This offer was now accepted, and the opposing forces quickly reformed their lines and prepared to march. As the drummer of the Washington Cornet Band beat a simple cadence at half past eight o’clock, the mass of citizens and soldiers began to march westward.

When they reached City Hall, at the corner of Meeting and Broad Streets, both columns turned to the north while still keeping to opposite sides of the street. Someone in the mob cried out “play ‘Dixie!’” and a resounding chorus of white voices repeated the call. As the assembled mass, now augmented by hundreds of black citizens, passed the Fireproof building at the corner of Chalmers Street, the members of the Washington Cornet Band lifted their dented instruments and launched into the refrain of that “favorite tune.” In response to the sound of “Dixie,” said the Daily News, “one long, loud and continued shout burst from the throats of the delighted crowd, and made the welkin [sky] ring.”

The cheers of the white citizens were accompanied, however, by an equal and opposite reaction from the black citizens in attendance, who “shouted fully as vociferously” their contempt for the nostalgic Southern anthem. “At this moment,” said the newspaper, “some policemen ordered the band to stop playing ‘Dixie.’” The African-American musicians complied and lowered their instruments. An angry mob then turned on the police, who responded by quickly forming a line above the intersection of Meeting and Queen Streets to stop the procession. What provocation had inspired the police to “charge bayonets” on the people, one citizen asked, “unless cheering the tune of ‘Dixie’ can be considered such?” Indeed it can. The huge white crowd hesitated, and even recoiled for a moment, but then, without musical accompaniment, they “quietly walked through the opposing force” towards their destination, the Charleston Hotel.

North of Market Street, the band piped up “Home Sweet Home” as the baseball teams entered the south end of the hotel’s portico, at the corner of Hayne Street. Loud calls for “Dixie” echoed through the crowded vestibule as the guests filed in, and the resounding cheers completly drowned the brassy music. After a series of impromptu speeches made atop the hotel counter, the baseballers checked into their rooms and went to supper.[5] The visiting Savannah musicians were also hungry, no doubt, but they had separate plans. According to a brief note published in an earlier newspaper, the members of one of Charleston’s own African-American bands, led by Peter Mazyck, had arranged to entertain the members of the Washington Cornet Band during their stay. I’m sure their weekend included a colorful series of jam sessions and home cooking, but the white newspapers provided no further coverage of that interesting storyline. It’s worth noting, however, that the Charleston Courier mentioned that the vice-president of the Carolina Base Ball Club, Mr. J. A. Moroso, coordinated with the proprietor of the Charleston Hotel, Mr. E. H. Jackson, to provide refreshments and lodgings for the visiting black musicians.[6]

The Riot on Calhoun Street:

After the visitors had eaten a quick supper at the hotel, the members of the Washington Cornet Band gathered in Meeting Street in front of the building’s massive portico and performed a brief public serenade. The music, no doubt composed of less strident airs than those heard earlier in the day, attracted a modest crowd of several hundred citizens, both black and white. When the peaceful music concluded and the band retired for the evening, around ten o’clock, the crowd gradually dispersed into the moonlit streets.

One group of African-American listeners, numbering somewhere between a few dozen and two hundred people, headed west to King Street, then turned northward. Near Wentworth Street, they encountered a group of around three dozen white men, and a few disparaging words were exchanged in passing. Those who heard the insults stopped and confronted the other group. Tempers immediately flared to white-hot rage, primed by weeks of racial tension. As the Charleston Courier later stated, the people were in an “excited state” after the tense scene on Broad Street earlier in the evening, “and to raise a row was no difficult matter.” At the corner of King and Wentworth Street after 10 p.m., harsh words escalated to shouting insults. A pistol shot rang out, and the large black crowd darted northward in unison, away from the scene, with the white men in pursuit.

When the head of the retreating crowd reached Calhoun Street, they began lobbing bricks and rocks southward at their pursuers near George Street. Some of the retreating mob turned west on Calhoun Street and finding themselves still pursued as they approached Coming Street, began firing pistol shots at their white followers. Some of the white runners drew their own revolvers and fired back. At least twenty shots rang out. One black man was shot through the arm, while a white man lost a finger, but there were no further reports of injuries or damage. A squad of policemen carrying Winchester rifles and bayonets came charging through Calhoun Street and succeeded in dispersing both parties. Having quashed that brief riot, the police force marched down the length of King Street, bayonets first, and cleared the busy street. By midnight on that hot Saturday night, the city was quiet, but restless.[7]

A Day of Rest:

On Sunday, August 15th, the purportedly devout members of the opposing baseball clubs attended various church services in the morning and then spent the afternoon as tourists usually do. The proprietor of the Charleston Hotel generously provided a number of carriages for the visiting sportsmen, enabling them to drive around the city and into the suburbs, seeing the obligatory local sights and enjoying the summer breeze and sunshine.[8] At the same time, Magistrate Robert DeLarge and a number of other prominent black men of Charleston hosted the members of the Washington Cornet Band. They, too, attended divine services, enjoyed some good home coking, and were generally entertained in a most hospitable manner.[9]

On Sunday, August 15th, the purportedly devout members of the opposing baseball clubs attended various church services in the morning and then spent the afternoon as tourists usually do. The proprietor of the Charleston Hotel generously provided a number of carriages for the visiting sportsmen, enabling them to drive around the city and into the suburbs, seeing the obligatory local sights and enjoying the summer breeze and sunshine.[8] At the same time, Magistrate Robert DeLarge and a number of other prominent black men of Charleston hosted the members of the Washington Cornet Band. They, too, attended divine services, enjoyed some good home coking, and were generally entertained in a most hospitable manner.[9]

Those attending Sunday services at Emanuel A.M.E. Church on Calhoun Street heard a sermon from the Rev. Richard Harvey Cain calling for peace in the face of racial disparities and insults. In contrast to the regular diet of white-supremacist rhetoric in Charleston’s mainstream newspapers, Rev. Cain had published a long rebuttal in the city’s black-owned newspaper, The Missionary Record. The Negros of South Carolina, he asserted, “deprecate every act, of whatever class of person, which tends to destroy the peace and order of this community.” African Americans had fought for liberty in the recent war and were now engaged in a righteous struggle for equality and justice. Rev. Cain wanted to assure white citizens that the black population was composed of “law-abiding men, and will be the last to break the peace, unless provoked to defend their rights against what they regard as flagrant violations.” But violence was the absolute last resort. “We are glad to know that we live in a community of white men who have more consideration for the welfare of the community and the maintenance of law and order, than the gratification of their hatred of the colored man.” While threats of violence and intimidation had come from newspapers in Georgia and across the South, Rev. Cain implored the people of Savannah to “keep the rowdies at home.” In response to this eloquent and reasonable essay, the editor of the Charleston Courier called it “balderdash,” while the editor of the Daily News condemned what he called “the “insolent tone” of Rev. Cain’s “bloody teaching,” and concluded that the black minister was simply “spoiling for a riot.”[10]

Game Day, August 16th:

When the sun rose over Charleston on Monday, August 16th, many in the city awoke with great apprehensions that a civil disturbance was imminent. Anecdotal reports of violent plots and plans were whispered all around town during the morning. A “strong rumor” circulated on Broad Street that South Carolina’s military governor, General Robert Kingston Scott of the U.S. Army, had telegraphed instructions to stop the baseball game from being played. That rumor was never substantiated, however, and plans for the afternoon game moved forward.

Around mid-day, a committee of fifteen prominent white citizens called on Mayor Pillsbury at his office, “with a view of cooperating with him in the preservation of the public peace.” In light of the “exciting events of Saturday evening,” said the committee, the city was now in a “feverish state” of anxiety over the possibility of further violence. Everyone knew that the mayor intended to post an armed force of policemen around the baseball field, and the committee felt that such a demonstration of power might actually provoke a violent response from the crowd. Perhaps it would be prudent to withdraw the armed guards some distance from the game, out of the sight of the baseball clubs. The white citizens volunteered that they themselves were prepared to counter any violent influence, if any should appear.

Mayor Pillsbury, as chief executive of the city government, said “he could not relinquish his right and responsibility in the matter of the preservation of the peace to any body of citizens, however good their intentions or however great their influence.” From his point of view, the sportsmen could have contributed to the preservation of peace by playing their second match game in Savannah, as originally planned. By insisting on moving the game back to Charleston—a move the Savannah club had resisted—the Charleston club was now responsible for having incited the present unrest. The mayor defended his plans to position an armed police force around the ball field, a plan that had been widely known for some days now, and he saw no good reason to change it.

The committee argued firmly for the withdrawal of the armed police, but the mayor was “immovable.” In light of the “taunts” published in the local newspapers about the “powerless” mayor, said Pillsbury, it was now “a matter of pride with him to show that the city authorities could and would enforce the laws.” Furthermore, several black militia companies had been parading that morning “in the upper part of the city,” contrary to his request to postpone such maneuvers, and the situation was sufficiently tense to warrant all possible caution. The mayor, therefore, “politely but positively declined to follow the counsel which had been offered.”

By two o’clock on a sweltering Monday afternoon, the perimeter of the temporary ball field at the west end of Broad Street was guarded by a force of policemen armed with Winchester rifles and posted at short intervals. These stationary guards were augmented by a roving patrol of police sentinels walking inside the perimeter, while Police Captain Hendricks and the main body of the police force stood at the ready a short distance to the east. Several hundred feet further eastward, two companies of United States infantry were posted at the main police guard house at the southwest corner of Meeting and Broad Streets, just in case their services were required.

Meanwhile, back at the Charleston Hotel, the members of the Savannah Base Ball Club sat down to dinner at 1 p.m. and then strapped on their gray flannel uniforms and spiked shoes for the game. At 2 p.m. they boarded a trio of horse-drawn omnibuses, one for each of the two clubs and one for the Washington Cornet Band. After a short drive to the grounds at the west end of Broad Street, each club found shelter under a pair of tents pitched near the banks of the Ashley River, on opposite sides of home plate. Another tent, at the eastern edge of the delineated field, shaded the official scorekeeper for each team, and a fourth tent was erected to shade the cool brass band.

The umpire cried “play ball” at 2:40 p.m., at which time a reporter observed that there only “about three hundred whites and not more than forty negroes” present. By the time the first inning was well underway, however, the crowd had swelled to at least twenty-five hundred spectators. Most of the shops in town had closed early because everyone wanted to witness the game, and all of the downtown railroad employee had walked off the job at one o’clock. African-American spectators formed a much smaller proportion of this audience than at the riotous game played on July 26th. The Charleston Daily News estimated that their numbers, including women and children, “could not have been more than four hundred.”

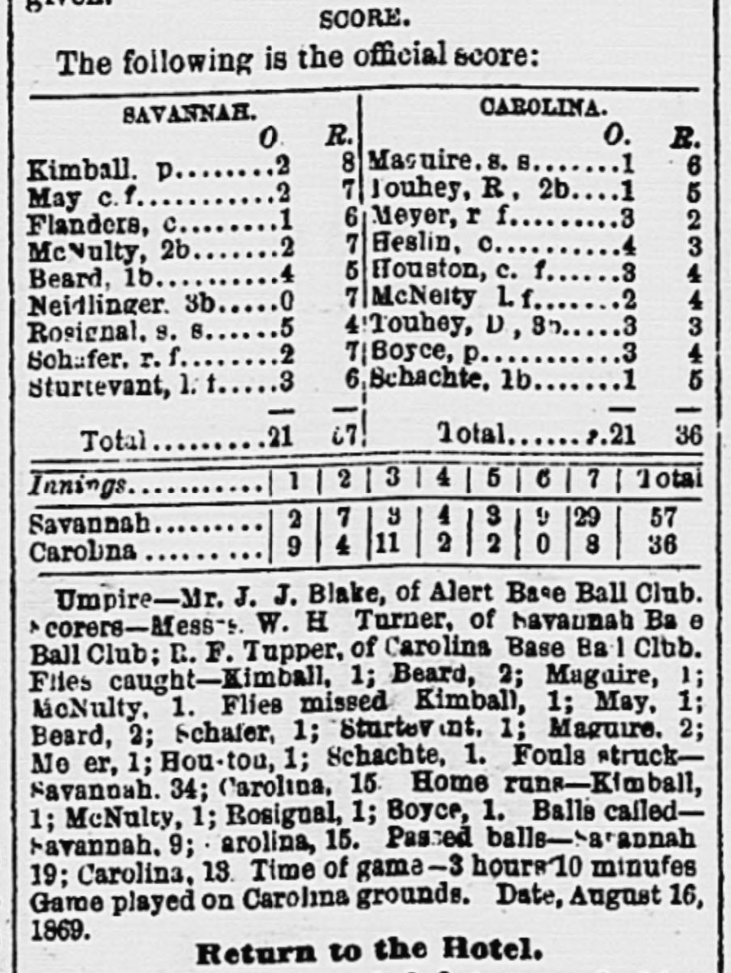

The friendly game of baseball played under a hot August sun enfolded in the usual lazy manner over the next three hours. The local Carolina club, dressed in white flannel, “were in high glee and seemed to have things all their own way” during the first three innings. That trend “put the Savannah boys on their mettle,” however, “and they made up their minds to have another shake for it.” The Carolinas then made a series of “occasional muffs,” which they blamed on the “very bright” sun that “interfered with the operations of the fielders.” The Savannah “nine” rebounded steadily during the fifth and sixth innings, after which the game was tied at the score of 28 to 28.

Although there was not the least hint of physical violence, the spectators at the Carolina-Savannah match witnessed a dramatic collision of opposing fortunes during the game’s seventh inning. This turn of events was not caused by rioting or hostility of any kind, but by exhaustion and, perhaps, heat stroke. Although the tiring Carolina club batted a respectable eight runs during the first half of the inning, the Savannah “boys” then took the offensive and scored an amazing twenty-nine runs during their turn at bat. The local press reported that “the fielding of the Carolinas in this inning was very loose, no activity being displayed. . . . Had they held up and played as well as they did during the first six innings, they could not have been badly beaten.” But the local boys were exhausted and “demoralized,” and they knew they’d been beat.

As clouds began to obscure the summer sun at the close of the seventh inning, just a few minutes before six o’clock, the two teams agreed to call the game and retire. The crowd rushed to the scoring tent and waited anxiously to hear the result. After a few moments of tabulation, the umpire announced that Savannah had won by a score of 57 to 36. The crowd erupted into a series of cheers for each of the teams, and everyone seemed relieved that the game had unfolded without violence. The baseball clubs and the band stepped aboard their waiting omnibuses and began a slow musical procession up Broad Street towards the Charleston Hotel, accompanied by the familiar strains of “Dixie.” Many hundreds of citizens walk along and behind the horse-drawn buses, cheering and dancing to the band music filling the air, while citizens along the route waved handkerchiefs and saluted the raucous parade.

As clouds began to obscure the summer sun at the close of the seventh inning, just a few minutes before six o’clock, the two teams agreed to call the game and retire. The crowd rushed to the scoring tent and waited anxiously to hear the result. After a few moments of tabulation, the umpire announced that Savannah had won by a score of 57 to 36. The crowd erupted into a series of cheers for each of the teams, and everyone seemed relieved that the game had unfolded without violence. The baseball clubs and the band stepped aboard their waiting omnibuses and began a slow musical procession up Broad Street towards the Charleston Hotel, accompanied by the familiar strains of “Dixie.” Many hundreds of citizens walk along and behind the horse-drawn buses, cheering and dancing to the band music filling the air, while citizens along the route waved handkerchiefs and saluted the raucous parade.

At the entrance to the Charleston Hotel, the band again played “Dixie” and the “Bonnie Blue Flag” as the sportsmen filed into the vestibule and returned to their rooms for a bit of liquid refreshment. The baseballers and their boosters returned to the lobby at half past nine in the evening and marched, “arm in arm,” into the dining room for an elegant fraternal meal. Supper was followed by a number of rousing tunes from the band and a series of congratulatory speeches and expressions of fellowship. The entire affair transpired without the least disturbance, and “the assemblage dispersed at a late hour, after having spent a most delightful evening.”[11]

The Departure:

On Tuesday, August 17th, the members of the Carolina Base Ball Club roused their visiting opponents late in the morning and dragged them, with the Washington Cornet Band, to the ferry landing at the east end of Market Street. After crossing over the Cooper River to the village of Mount Pleasant, the two teams indulged in a carefree afternoon of sports and recreation. They pitched horseshoes, played billiards, held a stag dance, played a few innings “muffin” baseball, engaged in a childish mock riot, rode the new-fangled velocipedes, and splashed in the ocean surf. At half past six o’clock, the sportsmen and the band boarded the ferry and returned to Charleston.

Dinner at the hotel was followed by the packing of luggage and the settling of bills. At a quarter past eight, the two clubs and the band climbed aboard their respective horse-drawn omnibuses and made a circuit of the town, shouting and playing music as they passed through the streets. They arrived at South Atlantic Wharf at nine o’clock and commenced to say their farewells. Surrounded by more than three hundred white well-wishers and about fifty African-American spectators, the visitors and their luggage went on board just before the signal to cast-off whistled at 9:30.

Dinner at the hotel was followed by the packing of luggage and the settling of bills. At a quarter past eight, the two clubs and the band climbed aboard their respective horse-drawn omnibuses and made a circuit of the town, shouting and playing music as they passed through the streets. They arrived at South Atlantic Wharf at nine o’clock and commenced to say their farewells. Surrounded by more than three hundred white well-wishers and about fifty African-American spectators, the visitors and their luggage went on board just before the signal to cast-off whistled at 9:30.

As the steamboat Dictator glided gently away from the wharf among a chorus of cheers, the departing band once again lifted their dented horns and played “Dixie.” The crowd on shore erupted in joyous shouts at the sound of the nostalgic anthem, and someone onboard the steamer “fired off his pistol by way of a parting salute.” In the ensuing moments, said the Charleston Daily News, there commenced “a lively contest” of celebratory gunfire, to see “whether the twenty men on board could fire more rapidly and more shots than the three hundred or more men on the wharf.” This exuberant display was punctuated by a single shot from the signal cannon in the bow of the steamboat. An eye-witness to this scene estimated that “there were about seven hundred shots fired in three or four minutes.” The African-American spectators assembled at the wharf “skedaddled” from the scene at the sound of the first shot, said the newspaper. No doubt fearing a spontaneous eruption of racial violence, the black crowd darted so quickly and so uniformly into the moonlight that one observer noted that “they appeared to be only an indistinguishable, rapidly moving black body.”[12]

The Epilogue:

Notwithstanding all the preparations for violence, the baseball game on August 16th, 1869, passed without incident. This fact was not a sign of universal harmony in Charleston, however, as the specter of racial tension continued to undermine the city’s peace and prosperity for many years to come. While members of the white community proudly took credit for bullying their opponents into submission, and stated with glee that Mayor Pillsbury could “chew the bitter cud of [unfavorable] reflection on his conduct,” black leaders like Rev. Richard Cain gave thanks that the episode had passed with relative calm. “There never was any intention on the part of the colored people to create a riot,” said Rev. Cain in an editorial, “they are more intent on obtaining work. Now that it is all over . . . we say to our friends, ‘Let us have peace.’” Typical of the distorted relations of that era, the editor of the Charleston Daily News interpreted Cain’s words as the whining excuse of a “would be rioter” who backed down when faced with the “occular [sic] demonstration that there are still some white men in Charleston.”[13]

In the 150 years that have passed since the Charleston baseball riots of 1869, the state of race relations in this city has improved considerably, and the game of baseball eventually steered away from its early discriminatory character. Thousands of people now visit Charleston’s Joe Riley baseball stadium and other venues every year without the least concern for riots or mob violence. Despite these advances, however, painful memories of past injustice still linger in our community and beyond. Just as it did in 1869, the sound of “Dixie” still has the power to divide, but not to conquer.

[1] See Charleston Daily News (hereafter Daily News), 16 August 1869, page 1; and page three of Daily News, issues of 6 and 9 August 1869; Charleston Daily Courier (hereafter Daily Courier), 13 August 1869, page 1.

[2] Daily Courier, 13 August 1869, page 1; Daily News, 14 August 1869, page 3.

[3] Daily News, 13 August 1869, page 3, “Base Ball”; Daily News, 14 August 1869, page 3.

[4] Daily News, 14 August 1869, page 2, “Our Guests and Our City.”

[5] Daily News, 16 August 1869 (Monday), page 3: “Our Savannah Guests.” Rev. Richard Harvey Cain (1825–1887; a member of the S.C. Senate, 1868–72) later disputed this report of the day’s events as an example of racially biased reporting.

[6] The preceding narrative of the events of 14 August 1869 is based on the lengthy report in Daily News, 16 August 1869, page 3, “Our Savannah Guests”; and Daily Courier, 16 August 1869, page 3, “Base Ball.” References to Mazyck’s band appear in Daily News, 13 August 1869, page 3, “Base Ball”; and Daily Courier, 13 August 1869, page 1, “Peace.”

[7] Daily News, 16 August 1869, page 3, “Our Savannah Guests”; Daily Courier, 16 August 1869 (Monday), page 3, “Base Ball.”

[8] Daily News, 16 August 1869, page 3, “Our Savannah Guests.”

[9] Daily Courier, 16 August 1869, page 3, “Base Ball.”

[10] The full text of Cain’s essay appears in Daily News, 16 August 1869, page 3, “Our Modern Cain.” See also Daily Courier, 16 August 1869, page 1, “Poor Old Daddy Cain.”

[11] Daily Courier, 17 August 1869, page 1, “The Base Ball Match”; Daily News, 17 August 1869, page 3, “Our Savannah Guests” and “Crumbs”; and Daily News, 16 August 1869, page 3, “Close the Stores.”

[12] Daily News, 18 August 1869, page 3, “Our Savannah Guests.”

[13] Daily News, 17 August 1869, page 3, “Crumbs”; Daily News, 18 August 1869, page 2, “The Peace of the City”; Daily News, 23 August 1869, page 3, “The Late Visit of the Savannah Club.”

PREVIOUS: The Charleston Baseball Riots of 1869, Part 1

NEXT: The Evolution of Charleston’s Name

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments