The Charleston Riot of 1919

Processing Request

Processing Request

Today marks the centenary of one of the biggest public disturbances in Charleston’s history—the so-called “race riot” of 1919. Late on the night of Saturday, May 10th, young white sailors fueled by racial hatred roamed the heart of the city, smashing property and spilling blood as they went. It was an ominous beginning to what became known across the United States as the “Red Summer.”

Between February and October of 1919 (mostly May-August), there were more than three dozen outbreaks of racially-motivated riotous disturbances across the United States, in which scores of African-Americans were killed and lynched. The noted writer, James Weldon Johnson, described these months of widespread bloodshed as the “Red Summer” of racial violence. More than fifty years after the end of slavery in America, people of African descent were still struggling to gain the freedom to exercise their constitutional rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

The Red Summer was also coincident with the demobilization of U.S. troops following the end of the Great War, or World War I, which ended on November 11th, 1918. The United States officially entered the war in April of 1917, at which time hundreds of thousands of African-American men volunteered or were drafted into the armed forces to serve both at home and abroad. Their participation in this international conflict opened doors to new rights and forms of civic engagement, which awakened new motivations for public discourse about the state of race relations in America. That discourse was welcomed by many, but large numbers of white Americans, in the Southern states and beyond, were openly hostile to any disruption the racial status quo of “Jim Crow” segregation.

Closer to home, the war’s principal impact in the Charleston area centered around the Navy Yard that opened along the banks of the Cooper River in 1901. In the spring of 1917, it became the headquarters of the U.S. Sixth Naval District. Over the ensuing two years, the Charleston Navy Yard swelled with sailors, ships, and construction projects. Thousands of reserve sailors passed through the new Naval Training Camp, adjacent to the Navy Yard, and thousands of returning sailors passed through the Charleston yard on their way back home in the months after the conclusion of the war.[1]

These sailors, as well as smaller populations of local Army soldiers and Marines, were stationed on the northern fringes of Charleston Neck, outside the city proper. When they were granted leave or “liberty,” however, the servicemen usually rode taxies or government buses into the city for recreation and amusement. Charleston was a dry city after the war, however, because the state of South Carolina had prohibited the sale of alcohol in 1916 and strengthened its anti-liquor law when the war began in 1917. That’s right—alcohol was illegal in the Palmetto City and State long before the prohibitive Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution came into force on January 17, 1920.

On leave, young sailors and soldiers from all over the United States, with a variety of backgrounds and attitudes, streamed into the city looking to unwind and have a good time. At the turn of the twentieth century, Charleston’s red-light district, euphemistically called the “segregated district” by the city government, encompassed a few urban blocks bounded by King Street to the east, Archdale Street to the west, Queen Street to the south, and Beaufain Street to the north. With the entry of the United States into the Great War in 1917, and the expected influx of soldiers and sailors into the area, however, the Federal government pressured Charleston’s City Council to break up the brothels and speakeasies in the “segregated district” and to provide more wholesome entertainment for servicemen. That work was mostly complete by 1919, but stories of the neighborhood’s racy reputation persisted among young men of a certain age.

Charleston was a diverse community in 1919, but its color was fading as each year passed. The population of urban Charleston in 1910 was 58,833 people, of whom approximately 52% were African American. In the ensuing years, African Americans across the Southern states began moving northward in a phenomenon known as the Great Migration. At the same time, the Charleston Navy Yard ramped up its operations and personnel during the Great War. As a result of these events, the city’s population in 1920 (67,957) was less than 48% black. That demographic shift has continued over the past century, so that persons of African descent now form approximately 22% the population of urban Charleston.[2]

Charleston was a diverse community in 1919, but its color was fading as each year passed. The population of urban Charleston in 1910 was 58,833 people, of whom approximately 52% were African American. In the ensuing years, African Americans across the Southern states began moving northward in a phenomenon known as the Great Migration. At the same time, the Charleston Navy Yard ramped up its operations and personnel during the Great War. As a result of these events, the city’s population in 1920 (67,957) was less than 48% black. That demographic shift has continued over the past century, so that persons of African descent now form approximately 22% the population of urban Charleston.[2]

On the evening of Saturday, May 10th, 1919, a series of incidents occurred that snowballed into a large-scale riot that overwhelmed the rule of law in downtown Charleston. The principal participants in this event were visiting U.S. Navy sailors, called “bluejackets” by the press, and local African-American men. Before I launch into my attempt to narrate this story, I’d like to mention a few caveats to help us comprehend this outrageous event and to assess the existing literature about it.

The initial reports in the Charleston newspapers, published in first 48 hours after the riot, contained some rumors, inaccuracies, and some garbled statements that reflect the hurried work of beat reporters and pressroom typographers. These shortcomings reflect the journalistic pitfalls inherent to the business of covering breaking news. Factual clarity is often difficult, if not impossible, in the early hours of a big, breaking story with lots of moving parts. To exacerbate the confusion, these flawed and hurried local reports were then communicated to other cities via telegraphic wire, and subsequently repeated and even exaggerated by other newspapers across the nation. As modern readers, we need to digest and interpret all of these newspaper reports with a measure of caution, especially since they were produced during an era of ingrained racial discrimination. In recent years, some historians looking back at these newspaper accounts have repeated some of the inaccuracies and rumors. Several writers have also made good use of the clarifying facts found in the U.S. Navy’s lengthy report of its investigation into the riot of 1919, but confusion about this event continues to linger in our community.[3]

Adding to the factual confusion present in the contemporary newspaper reports, authors less familiar with Charleston have misidentified some of the local characters and misinterpreted some of the geography and chronology of the events in question. I hope to correct some of those errors, but, in the interest of time, I’m going to omit a few details from my summary. My goal is to lay out the known facts in a logical fashion in order to facilitate a better understanding of this important local tragedy.

The Riot Begins:

The trouble began sometime after seven o’clock on Saturday evening, May 10th, but the precise cause was never fully determined. In the immediate aftermath of the riot, the local newspapers reported several conflicting theories about its origin and noted that there were “various reports” in circulation. One story mentioned a “pool room fight” as the initial trigger, while another mentioned a sailor being unhappy about the illegal whisky he purchased from a black man. Others reported that they heard that a black man had shot a white sailor. Despite this convoluted mixture of hearsay and distorted facts, all of the contemporary sources agree that the disturbances commenced somewhere near the intersection of Beaufain Street and Charles (Archdale) Streets. (Archdale Street, of ancient origin, was renamed Charles Street in 1916, then renamed Archdale Street in 1927.)[4]

The Navy’s official investigation concluded that the most likely cause of the riot was a random sidewalk encounter between two white sailors and a black male. Sixteen-year-old Roscoe Coleman of Ohio and eighteen-year-old Robert Morton of Texas, both on leave from the Charleston Naval Training Camp, passed an unidentified black man on a sidewalk near the intersection of Beaufain and Archdale Streets. Some sort of spontaneous incident then occurred. Most likely it was a case of the black male failing to step aside in deference to the white men, as had been customary in the past. One newspaper report identified that black male as Isaac (but actually Isaiah) Doctor, a twenty-two year-old laborer who lived with his parents nearby, at No. 155 Market Street.[5]

The Navy’s official investigation concluded that the most likely cause of the riot was a random sidewalk encounter between two white sailors and a black male. Sixteen-year-old Roscoe Coleman of Ohio and eighteen-year-old Robert Morton of Texas, both on leave from the Charleston Naval Training Camp, passed an unidentified black man on a sidewalk near the intersection of Beaufain and Archdale Streets. Some sort of spontaneous incident then occurred. Most likely it was a case of the black male failing to step aside in deference to the white men, as had been customary in the past. One newspaper report identified that black male as Isaac (but actually Isaiah) Doctor, a twenty-two year-old laborer who lived with his parents nearby, at No. 155 Market Street.[5]

Doctor is alleged to have “jostled through two bluejackets” as they passed on the sidewalk. The sailors then “remonstrated” or complained out loud, and Doctor reportedly “hurled epithets at the two white men” and kept walking. The sailors began following him, joined by other white sailors and a few civilians. Words were exchanged, threats were made, and tempers flared. The black man allegedly threw a brick at the white crowd, and the sailors chased him down an alley way. The chronology of the subsequent events is a bit scrambled in the surviving records, but the small sidewalk scene appears to have caught the attention of more nearby sailors who started rushing to the scene to discover the story behind the raised voices. After more verbal taunting and rock throwing, an unidentified black man emerged with a pistol and fired into the air. The frightened white crowd scattered, but their anger did not dissipate.[6]

Police officer Chris Redell was standing at the corner of King and Wentworth Streets when he heard several shots fired around 8:50 p.m. The shots “seemed to come from the direction of Market and Charles [Archdale Street],” he later testified, and so he starting running towards the noise. When he arrived at that place he was told that several sailors had been taken away wounded. On arriving at 55 Charles Street (no such address exists, but it was probably at or near the southwest corner of Beaufain and Archdale Streets; or perhaps he meant 155 Market Street), Officer Redell said bystanders informed him that the sailors “had been attacked from that house, and while there the bluejackets attempted to surround the house and gain entrance.” The policeman “rounded that group up and put the men in charge of several [Navy] provost guards.”[7]

Meanwhile, rumors were spreading through the neighborhood that a black man had shot a sailor. This news incited a wave of anger that inspired a rush of people away from the bustling nightlife along King and Market Streets towards the scene of the alleged incident. About 9:30 p.m., Harry Police, the Turkish-immigrant proprietor of a billiards hall at the southeast corner of Market and Charles (Archdale) Streets reported that “several sailors came into this pool room and grabbed cues and billiard balls and ran out into the street.” After witnessing this act of theft, the black patrons already in pool hall “armed themselves in the same way” and ran out to join the raucous crowd in the street. In his later testimony, thirty-year-old Harry Police contradicted earlier reports that the riot had begun in his pool room. He steadfastly insisted there had been no fighting in his establishment, which he said closed as soon as the men departed with all his pool cues and billiard balls.[8]

At the same time, a bit to the east, white sailors and civilians raided two commercial shooting galleries, at 310 King Street and at 129 ½ Market Street. These were amusement-park-style indoor rifle ranges that were once a popular form of recreation for tourists. From these establishments, sailors carried away at least eighteen .22 caliber rifles, seven pistols, and dozens of boxes of ammunition, and began firing indiscriminately at African Americans.[9] At least two of the newly-armed sailors ran back to the west end of Market Street with a crowd of supporters, looking for vengeance against the black man who had thrown rocks at them earlier. The details of what happened next are obscure; they found or chased Isaiah Doctor into the open yard behind his house at 155 Market Street. The words they exchanged were not recorded, but it’s clear that passions were boiling over. Two sailors leveled their stolen rifles at Isaiah, and each man fired two shots.[10]

Almost immediately after the shots rang out, Police Chief Joseph Black and a posse of lawmen burst into the yard crowded with enlisted sailors and black men. Isaiah Doctor lay on the ground bleeding from a bullet wound in the chest. Sailors nearby pointed at the fallen victim and exclaimed that he had a concealed pistol. Chief Black quickly knelt and frisked Doctor. He later testified that he “could find no trace of any weapon, nor was there any signs that a scuffle had taken place.” Instead, said the chief, “I saw he was mortally wounded, and so Chief [Detective Clarence] Levy and myself took him into the [Market] street and put him in the [police] wagon” to rush him to the hospital.

Almost immediately after the shots rang out, Police Chief Joseph Black and a posse of lawmen burst into the yard crowded with enlisted sailors and black men. Isaiah Doctor lay on the ground bleeding from a bullet wound in the chest. Sailors nearby pointed at the fallen victim and exclaimed that he had a concealed pistol. Chief Black quickly knelt and frisked Doctor. He later testified that he “could find no trace of any weapon, nor was there any signs that a scuffle had taken place.” Instead, said the chief, “I saw he was mortally wounded, and so Chief [Detective Clarence] Levy and myself took him into the [Market] street and put him in the [police] wagon” to rush him to the hospital.

As the officers carried Isaiah Doctor to the wagon, the crowed pointed out two sailors, each holding .22 caliber rifles, as the assailants. Lieutenant Edward McDonald, who had accompanied Chief Black to the scene, took away their weapons and arrested private Jacob Cohen, of Baltimore, and private George Holliday, of Charlotte. Marching them out to the street as the wagon departed, Lieutenant McDonald asked the chief how he was supposed to transport the prisoners to the station house. Chief Black took control of the two sailors and sent Lieutenant McDonald back on patrol. Over the next half-hour, the chief of police walked the two prisoners just over a half-mile up St. Philip Street to the station, at the northwest corner of St. Philip and Vanderhorst Streets, followed by a menacing crowd of ten to twenty angry sailors. Chief Black remained calm, however, and managed to disarm several more sailors and squeeze a confession out of his prisoners as they marched northward.[11]

By this time, reported the Charleston Evening Post, “hundreds of sailors, some soldiers and later civilians, most of them spectators, swelled the proportions of a mob to a size that was beyond control of the police and there opened a wide hunt and chase of negroes by the enlisted men.” The Charleston News and Courier reported that “from this beginning, the disorders spread over a wide area,” as far south as Queen Streets and as far north as Line Street. “Persons who were in touch with the disorders in their various stages said that comparatively few white civilians were involved in the rioting. Every sort of weapon was used during the series of melees, from pistols and rifles down to ordinary brickbats.”[12] “Just how word of the disorder spread so rapidly among the bluejackets in town on leave is not explained,” reported the Columbia newspaper, The State, “but in a very few minutes about 2,000 were in the mob which shouted ‘Get the Negroes,’ and similar phrases. According to the police and other reports, several of the victims were innocent of any offense to the bluejackets.”[13]

Commencing from the area around the intersection of King and Market Streets, the heart of the riotous crowd worked its way northward along King Street. Around midnight, sailors saw a black youth duck into a store at 305 King Street, Fridie’s Central Shaving Parlor, a barber shop “run by negroes for white men.” The crowd went after him, but the door was locked and the lights were out. Fueled by rage, the mob of sailors smashed through the windows and destroyed the shop’s interior. They searched through the rubble but, finding no prey, moved on. A young man named Augustus Bonaparte later testified to the Navy’s investigation that he had hidden inside Fridie’s shaving parlor until it was quiet. Once he stepped out into King Street, however, he was attacked and beaten by sailors while a policeman stood by and watched.[14]

At Marion Square, a streetcar operator coming north from Broad Street refused to stop for the mob of sailors. One of the bluejackets climbed atop the moving vehicle and “jerked off the trolley”—the electrical umbilical that connected the machine to the power grid. Once the car stopped rolling, sailors “entered the car, took a negro out, beat him and then shot him down.” Other sailors stopped a hack (hired car) on King Street, removed, beat, and robbed the African-American driver, William Randall, and took his vehicle on a joyride down King Street. Meanwhile, near the intersection of King and Market Streets, another group of sailors forcibly removed a random black man from another streetcar, threw him to the sidewalk and shot him. “Persons in a fashionable restaurant,” said the newspaper, “were unwilling spectators of this.”[15]

The city’s normal police patrol was quickly overwhelmed by the scale of the Saturday night riot. Off-duty officers began streaming into the station house as soon as news of the mayhem spread through the urban neighborhoods. Police Chief Black was on the telephone with mayor Tristram Hyde, who was in communication with the commandant of the Navy Yard, Rear Admiral Benjamin C. Bryan. A small force of Navy provost guards (military police) were already in town, having been in the custom of accompanying the sailors on liberty into the city, but additional resources were now desperately needed. The military responded by dispatching scores of additional provost guards and more than a hundred marines from the Navy Yard, all of whom began streaming into town shortly after midnight.

The government vehicles carrying the fresh provost guards and marines unloaded at the police station, at the corner of St. Philip and Vanderhorst Streets. From that point the soldiers headed east into King Street and began fanning out in groups of three. Dressed in khaki uniforms and armed with rifles and fixed bayonets, the marines’ first instruction was to tell everyone they found in the streets—black or white, civilian or sailor—to go home and stay there. Rioters in uniform were instructed at gunpoint to board one of the government trucks following the marines, which would transport them back to the Navy Yard. Civilians found on the street were stopped and searched for concealed weapons.[16]

Marching from the police station, the marines followed Vanderhorst Street eastward to King Street and then spread to the north and south. At John Street, reported the News and Courier, “they deployed and took possession of the situation.” “At King and John a negro was seen on a street car with his wife. A bluejacket went in with a stick and ordered him off the car, and as he got off the mob pitched on him. The marines had come up in the meantime with fixed bayonets, and held the crowd back while the negro made his escape on John street, going toward Meeting.” “In the next block [north of John Street,] another negro was found in a restaurant and pulled out. The marines took him in charge, and at Radcliffe [Street,] a squad [of marines] was thrown across the street to protect him and he was turned loose and ran for his life.”[17]

Marching from the police station, the marines followed Vanderhorst Street eastward to King Street and then spread to the north and south. At John Street, reported the News and Courier, “they deployed and took possession of the situation.” “At King and John a negro was seen on a street car with his wife. A bluejacket went in with a stick and ordered him off the car, and as he got off the mob pitched on him. The marines had come up in the meantime with fixed bayonets, and held the crowd back while the negro made his escape on John street, going toward Meeting.” “In the next block [north of John Street,] another negro was found in a restaurant and pulled out. The marines took him in charge, and at Radcliffe [Street,] a squad [of marines] was thrown across the street to protect him and he was turned loose and ran for his life.”[17]

At Morris Street, six sailors and a civilian fired shots into a shoe repair shop managed by a black cobbler named James Freyer. Although the proprietor was not injured, a black youth named Peter Irving, a thirteen-year-old apprentice, was shot in the back while hiding inside the shop where he worked and lived. The boy was instantly paralyzed from the waist down, and never walked again. From that point, the core of the white mob continued moving northward along King Street, “searching for negroes.”[18]

At Columbus Street, the northern end of the King Street commercial district at that time, the blood-thirsty crowd paused. “Some of the men wanted to go further,” reported the News and Courier, “saying that all kinds of negroes could be found further up,” but the marines were now encircling and subduing the mob. Pointing their bayonets at the bluejackets, the marines made “every man in uniform” get into the middle of King Street and march eastward along Columbus Street to Meeting Street. At the intersection of Meeting and Columbus Streets they found a line of streetcars and a host of government vehicles assigned to carry the marauding sailors back to the Navy Yard. The black passengers on a streetcar traveling southward through the same intersection saw the mob turning into Meeting Street and “hid under the seats until they were out of the danger zone.”[19]

Between one and three a.m., there were other acts of violence committed across the city, but the riot eventually dissipated. Like a passing hurricane, the sound and the fury gradually diminished as soon as the marines succeeded in packing the eye of the storm onto buses and streetcars bound for the Navy Yard. The marines were undoubtedly responsible for successfully diffusing the situation, but they were not entirely neutral participants. Isaac Moses, for example, was running home from work when marines shot at him for failing to obey their order to halt. The bullets convinced Moses to stop, but the enraged marines cursed him, smashed his head with a rifle butt, and stabbed him in the leg with a bayonet. Black men had plenty of historical reasons not to trust white men in uniform, and this night was no exception. Marines ordered twenty-year-old William Brown and a companion to halt near King and Mary Streets, but the frightened men, on their way home, bolted. Chasing them eastward, the marines fired shots just before they turned onto Nassau Street. William Brown was hit in the knee and dropped to the ground just two blocks from his residence on South Street. “Why are you shooting me?” He asked the marines standing over him. “I was not doing anything.” The black youth had disobeyed an order that he did not hear, issued by a white soldier, and that was considered sufficient cause.[20]

Thanks to the “effective methods” pursued by the marines, order returned to the streets of Charleston sometime “between 2 and 3 o’clock” on the morning of Sunday, May 11th. A few injured parties were found on the streets as late as 6:45 a.m., but the riot was officially over by sunrise. Back at the police station, organized chaos ensued as men in a variety of uniforms streamed in and out of the building. Hundreds of bluejacketed sailors boarded streetcars and trucks back to the Navy Yard after midnight, but many others were confined to the station house overnight for lack of sufficient transportation. Early in the morning, Roscoe Coleman, the sixteen-year-old Ohio boy who may have started the riot, ran breathlessly into the police station and asked to be confined. He told officers “he was implicated in the shooting scrape with the other two sailors and that the walls [of the police station] looked better to him than the mob outside.”[21]

The Injured Charlestonians:

Charleston’s principal medical facility in 1919 was Roper Hospital, then located at the northwest corner of Calhoun and Lucas Streets. Beginning around 9:30 p.m. on the evening of May 10th, the hospital registered the arrival of dozens of injured parties, mostly black men. The staff was briefly overwhelmed with cases during late hours of that Saturday night, and additional surgeons were called in from the Navy Yard. The local newspapers included the names of a handful of white sailors who suffered cuts and bruises during the riot, but I’m more interested in the local victims who were either fighting or fleeing for their lives. Three men (not five, not six) died as a result of injuries received during the rioting, and the names of more than eighteen injured parties were identified in the Charleston newspapers.[22]

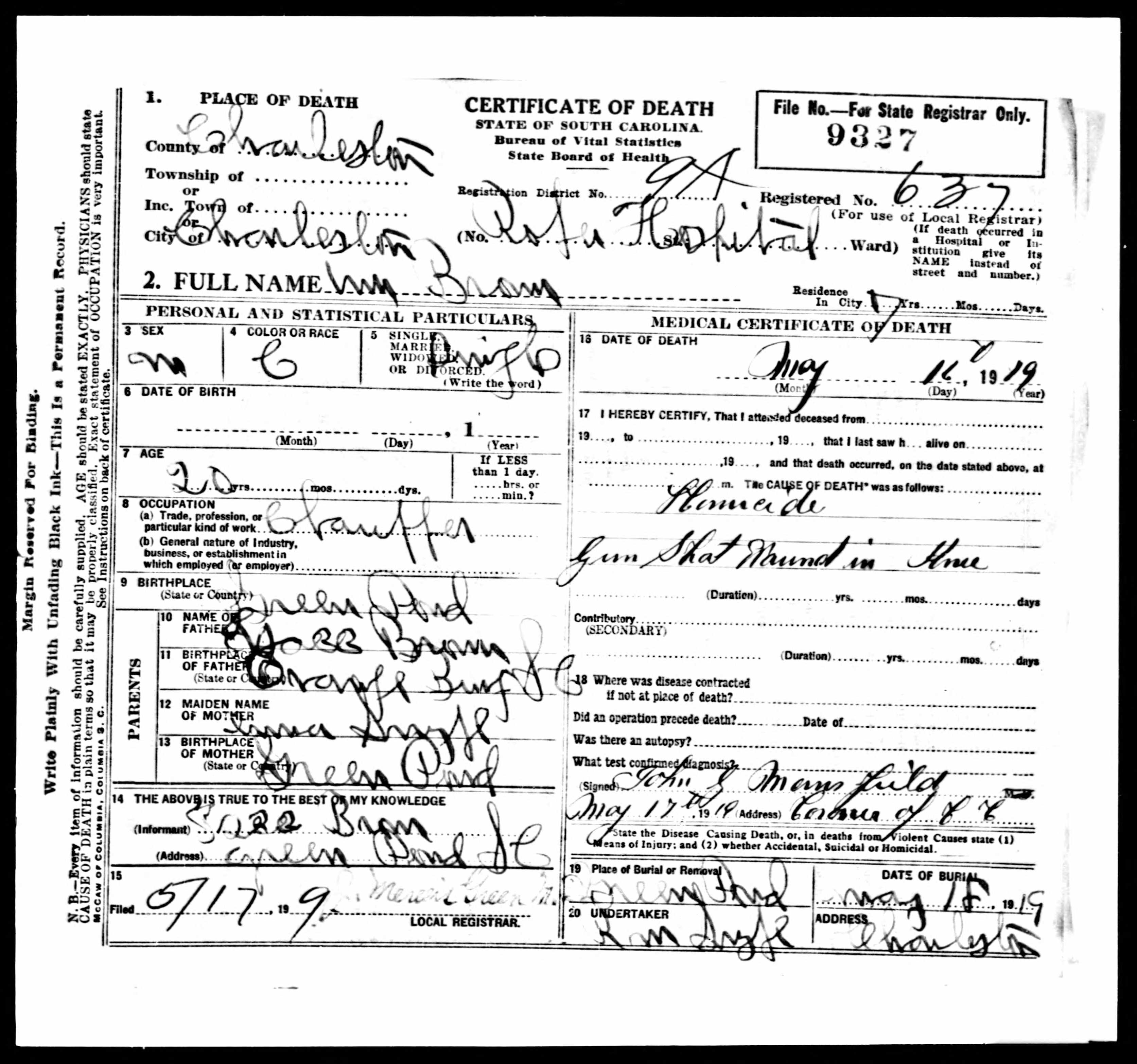

Twenty-two-year-old Isaiah (not Isaac) Doctor, shot in the chest behind his own home at the beginning of the riot, died of his wounds at Roper Hospital early on the morning of Sunday, May 11th, and was buried on John’s Island. Twenty-three-year-old James Tolbert (not Talbert), shot in the abdomen at an unknown location by unknown assailants, also died at the hospital at noon on Sunday. He was buried at Rockville, on Wadmalaw Island, and mourned by a young widow named Charlotte. Twenty-year-old William Brown, shot in the knee at the corner of Mary and Nassau Streets while running home, also died of his wounds at the hospital on Thursday, May 16th. He was buried near his birthplace in Green Pond, South Carolina.[23]

Twenty-two-year-old Isaiah (not Isaac) Doctor, shot in the chest behind his own home at the beginning of the riot, died of his wounds at Roper Hospital early on the morning of Sunday, May 11th, and was buried on John’s Island. Twenty-three-year-old James Tolbert (not Talbert), shot in the abdomen at an unknown location by unknown assailants, also died at the hospital at noon on Sunday. He was buried at Rockville, on Wadmalaw Island, and mourned by a young widow named Charlotte. Twenty-year-old William Brown, shot in the knee at the corner of Mary and Nassau Streets while running home, also died of his wounds at the hospital on Thursday, May 16th. He was buried near his birthplace in Green Pond, South Carolina.[23]

Moses Gadsden, “shot in leg at Lillianthal Row” (near King and Queen Streets).

Peter Irving, “shot in back, Morris Street.”

Nathan Flowers, “shot in leg, South street.”

Edward Campbell, “shot in back, East Bay street.”

Andrew Mitchell, “shot, Calhoun street.”

Edward Mitchell, “was injured at Meeting and Henrietta streets; incised and contused wounds of scalp; contusions of abdomen, right arm and both hands.”

Thomas Ingram, “cut about head and face, Meeting street.”

Gus Campbell, “shot in hip” and/or knee.

Clifford Singleton, “cut about shoulders and head; injured at Horlbeck and King Streets.”

Clifford Singleton, “cut about shoulders and head; injured at Horlbeck and King Streets.”

James Wilson, “shot in back.”

Charles [or Cyril] Burton, “cut about head and face.”

Moses Gladden, “kneecap shot off.”

Frank Fields, “shot in hip and leg, Radcliffe street.”

Frank Grant, “cut about body, injured leg, Citadel Square”

Isaac Moses, “bayoneted in leg.”

William Randall, the hack driver who was beaten and robbed in King Street, died a month later from a heart condition.[24]

The Aftermath:

On the morning of Sunday, May 11th, Mayor Tristram Hyde convened a meeting at the police station with Rear Admiral Francis E. Beatty, commandant of the sixth naval district, solicitor Thomas P. Stoney, Charleston County Coroner John G. Mansfield, Police Chief Joseph A. Black, and several naval officers. The municipal authorities turned over all but a few of the confined sailors to the military. The Navy suspended all leave for its unmarried personnel until further notice. Immediately after leaving the meeting, Mayor Hyde released a brief statement to the press: “There will be an investigation into the cause of the riot and steps will be taken to guard against future occurrences of the same order. Monday morning I will ask W. G. Fridie, whose barber shop on King street was demolished by the sailors, to draw up a bill of damages to be presented to the city government. This might set a precedent, but the negroes of Charleston must be protected. We are hoping that this morning saw the end of the disturbances, but if any action is taken by the negroes against the whites, or vice versa, I will ask that martial law be established.”[25]

On the morning of Sunday, May 11th, Mayor Tristram Hyde convened a meeting at the police station with Rear Admiral Francis E. Beatty, commandant of the sixth naval district, solicitor Thomas P. Stoney, Charleston County Coroner John G. Mansfield, Police Chief Joseph A. Black, and several naval officers. The municipal authorities turned over all but a few of the confined sailors to the military. The Navy suspended all leave for its unmarried personnel until further notice. Immediately after leaving the meeting, Mayor Hyde released a brief statement to the press: “There will be an investigation into the cause of the riot and steps will be taken to guard against future occurrences of the same order. Monday morning I will ask W. G. Fridie, whose barber shop on King street was demolished by the sailors, to draw up a bill of damages to be presented to the city government. This might set a precedent, but the negroes of Charleston must be protected. We are hoping that this morning saw the end of the disturbances, but if any action is taken by the negroes against the whites, or vice versa, I will ask that martial law be established.”[25]

On Monday morning, May 13th, Charleston City Recorder Theodore D. Jervey disposed of a number of “blotter” cases at the police station, mostly black men arrested for carrying concealed weapons (principally pocket knives and razors), as well as a few white sailors charged with inciting a riot. Only one white civilian was arrested. Alexander Lanneau, a nineteen-year-old salesman, asserted that he was merely doing what he believed to be his patriotic duty by supporting the men in uniform.[26]

At noon on Thursday, May 15th, County Coroner Mansfield held a two-hour court of inquiry at his office in the old Fireproof Building, located at the southeast corner of Meeting and Chalmers Streets. Besides the coroner and other elected officials, the scene included a Navy advocate, a stenographer, and the enlisted sailors implicated in the shooting of Isaiah Doctor—Roscoe Coleman, Jacob Cohen, and George Holliday. The bodies of Isaiah Doctor and James Tolbert were laid out on tables located in the northwest corner of the building’s ground floor (where I used to have a desk when I was first employed at the South Carolina Historical Society twenty years ago). A jury of six white men heard the coroner’s evidence and listened to the testimony of several police officers and Harry Police, the proprietor of the pool hall where the riot was then suspected of having begun. After hearing the cases and considering the evidence, the jury concluded that Doctor and Tolbert “came to their death from wounds inflicted with a rifle or pistol, in the opinion of the jury, in the hands of enlisted men while engaged in a riot on May 10th.” The identity of the assailants could not be positively confirmed.[27]

Shortly after the conclusion of the coroner’s inquiry on May 15th, the Navy convened it own court of inquiry and launched a deeper investigation into the riot. It held nineteen days of hearings aboard the USS Harford at the Navy Yard and summoned dozens of witnesses, both black and white. Privates Jacob Cohen and George Holliday were tried and acquitted for the manslaughter of Isaiah Doctor. The court found them guilty of rioting, however, and each man served a one year sentence in a naval brig. Two marines charged with fatally wounding William Brown were acquitted because Brown had failed to heed their order to halt. Private Roscoe Coleman, legally underage, was later acquitted of any wrongdoing and returned to duty. Several of the wounded black men petitioned the Navy for compensation for injuries sustained during the riot, but the Federal government ignored them. The Charleston chapter of the NAACP appealed to local white lawmakers to sponsor legislation to force the Navy’s hand, but they refused to act. The commander of the Charleston Navy Yard restored the sailor’s customary “liberty” to visit Charleston on the afternoon of May 20th, and the memory of the bloody affair soon evaporated from the minds of most white Charlestonians.[28]

Shortly after the conclusion of the coroner’s inquiry on May 15th, the Navy convened it own court of inquiry and launched a deeper investigation into the riot. It held nineteen days of hearings aboard the USS Harford at the Navy Yard and summoned dozens of witnesses, both black and white. Privates Jacob Cohen and George Holliday were tried and acquitted for the manslaughter of Isaiah Doctor. The court found them guilty of rioting, however, and each man served a one year sentence in a naval brig. Two marines charged with fatally wounding William Brown were acquitted because Brown had failed to heed their order to halt. Private Roscoe Coleman, legally underage, was later acquitted of any wrongdoing and returned to duty. Several of the wounded black men petitioned the Navy for compensation for injuries sustained during the riot, but the Federal government ignored them. The Charleston chapter of the NAACP appealed to local white lawmakers to sponsor legislation to force the Navy’s hand, but they refused to act. The commander of the Charleston Navy Yard restored the sailor’s customary “liberty” to visit Charleston on the afternoon of May 20th, and the memory of the bloody affair soon evaporated from the minds of most white Charlestonians.[28]

The Legacy of the 1919 Riot:

A century later, how do we describe the Charleston riot of May 10th, 1919, and how do we identify its legacy in our community? The riot of 1919 was an eruption of the festering racial tension that retarded this nation’s growth in earlier generations. Young white men “from off,” as we say in Charleston, were feeling anxious about the notion of advancing rights for African Americans, and lost control of themselves while visiting our racially diverse city. Was it a race riot? Yes, in the sense that the combatants were polarized into whites against blacks, but there is an important distinction here. Young white males were clearly and unquestionably the aggressors and the instigators. A few small incidents rapidly engendered a violent white mob that quite literally went “hunting” for “Negroes.” Charleston’s African-American population did not provoke or invite a fight; they simply became the target of the white mob’s fury. To their credit, many black men fought back and defended themselves with great vigor. While some black men did grab weapons and run towards the fight, it would be a mistake to say that the black community poured into the streets and added fuel to the flames of hatred. Most folks who happened to be on the streets that night ran home and hid. Even those hiding from the mob, like Augustus Bonaparte and Peter Irving, were not safe from the violence, however.

Rather than call it a “race riot,” I prefer to call it a “racially-motivated riot.” Charleston’s native black population was not an equal participant in the event, nor were they responsible for it in any way. Neither was this a home-grown affair, since the vast majority of the white aggressors were strangers to our community who came to town carrying their own prejudices. Race relations in Charleston in 1919 were not perfectly blissful, to be sure, but the diverse members of this community lived in a sort of détente nurtured by generations of familiarity. The editors of the Charleston newspapers did not print their opinion of the local events, but the editor of the Columbia newspaper, The State, did: “The affair last Saturday night . . . between sailors and negroes was not a Charleston riot, so far as the white citizenry of Charleston is concerned. . . . After the trouble began some Charlestonians may have participated in it, but it may be set down that they were in no sense representative of the community.”[29]

Although the Navy did arrest, prosecute, and incarcerate several of the white rioters who brought mayhem to Charleston in 1919, the judicial severity of those proceedings amounted to little more than a slap on the wrist for the young men. The local police, as well as the marines trying to restore order, repeatedly blamed the black victims of blatant crimes for their failure to stay in their customary place in society. As a result of these shortcomings, Charleston’s black community learned, once again, that they did not enjoy equal protection under the law, and that local authorities could not be trusted to protect their lives and liberties.

In 2019, Charleston is still struggling to cast off the shackles of innumerable past injustices. Many people in our community have never heard of the riot of 1919, despite the fact that it’s a critically important episode in the narrative of the city’s history. In order to improve relations between local authorities and the descendants of those people who were terrified and abused in 1919, it’s imperative that we talk about these events in an open and respectful manner. For two years now, I’ve had the pleasure of participating in a program to teach local Civil Rights history to the members of the Charleston Police Department, and the response from the force has been very positive. Learning about events like the riot of 1919 helps us to gain perspective on Charleston’s long trajectory from the capital of American slavery to America’s favorite vacation destination. And that’s the mantra of this Charleston Time Machine: talking about the past is often the key to unlocking our future.

[1] John Hammond Moore, “Charleston in World War I: Seeds of Change,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 86 (January 1985), 39–49.

[2] Current and historical population data for Charleston can be found in resources available on the website of the United States Census Bureau.

[3] See Lee E. Williams, “The Charleston, South Carolina, Riot of 1919,” in Southern Miscellany: Essays in History in Honor of Glover Moore (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1981), 150-76; David F. Krugler, 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 43-50, 214-19; Cameron McWhirter, Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America (New York: Holt, 2011), 41-50; Brian Hicks, In Darkest South Carolina: J. Waties Waring and the Secret Plan That Sparked A Civil Rights Movement (Charleston, S.C.: Evening Post Books, 2018), 66-68; Damon Fordham, True Stories of Black South Carolina (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2008), 92-94.

[4] Cameron McWhirter’s assertion that the riot began at the corner of King and George Streets, in the wake of a botched liquor deal, is based on a misreading of Lee Williams’s presentation of flawed, non-Charleston newspaper accounts of the event. See Williams, “The Charleston, South Carolina Riot of 1919,” 154-55; McWhirter, Red Summer, 41.

[5] The Charleston County Death Certificate for Isaiah Doctor, found on microfilm at CCPL, states that he was aged 22 years, born 1897, single, the son of Abraham Doctor and Letus Hollington, and recently resided at 155 Market Street. According to Walsh’s Charleston, South Carolina 1919 Directory (Charleston: Walsh Directory Company, 1919), 622, Abraham Doctor, laborer, also resided at 155 Market Street.

[6] Charleston News and Courier, 12 May 1919, page 8; Krugler, 1919, chapter 2.

[7] Charleston News and Courier, 16 May 1919, page 10.

[8] Charleston Evening Post, 15 May 1919, page 9; Charleston News and Courier, 16 May 1919, page 10. Harry Police, born 1889, arrived in New York in 1907 and settled in Charleston in 1909. In his naturalization papers, which you can access through CCPL’s subscription to Ancestry.com, Police stated that he was born on the island of Crete and identified himself as a subject of the Islamic Sultan of Turkey (he was thus one of the “Cretan Turks”). Sometime around the beginning of 1919 he opened a pool hall with seven tables at the southeast corner of Market and Charles (now Archdale) Streets, catering to a black clientele. The immigration officials in Charleston who recorded Mr. Police’s intention to become a citizen in 1912 identified him as white. Walsh’s 1919 Directory, page 116, lists 40 Charles Street as vacant. According to Walsh’s 1920 Directory, pages 116 and 466, Harry Police had a “pool room” at 40 Charles Street and resided at 163 Market Street. Mr. Police advertised the sale of seven pool tables in the Charleston Evening Post, 21 June 1924, page 12. His pool hall was in ground floor of the three-story brick building that is still known as No. 40 Archdale Street. Note that the city extended Market Street westward across Archdale to Logan Street at the end of 1952.

[9] Charleston News and Courier, 11 May 1919; page 1. Recreational shooting galleries continued as a form of indoor amusement in Charleston’s Market area until World War II, but they remained on the city’s license fee schedule as late as 1973. See Charleston Evening Post, 11 July 1973, page 8D, “Oldtime Licenses Still On Books.”

[10] The testimony of police Lieutenant Edward McDonald and Chief Joseph Black demonstrate that Isaiah Doctor was killed by rounds fired from .22 caliber rifles looted from the shooting galleries. See Charleston News and Courier, 16 May 1919, page 10.

[11] Charleston News and Courier, 16 May 1919, page 10; Charleston Evening Post, 12 May 1919, page 9; Charleston News and Courier, 12 May 1919, page 8. Note that George Holliday’s surname was rendered “Holloday” in all of the contemporary local news reports.

[12] Charleston Evening Post, 12 May 1919, page 9; Charleston News and Courier, 12 May 1919, page 8.

[13] The State [Columbia, S.C.], 12 May 1919, page 1, “Charleston Riot Costs Two Lives.”

[14] Charleston News and Courier, 11 May 1919; page 1; Krugler, 1919, chapter 2.

[15] These anecdotes are reported, with partially garbled text, in Charleston News and Courier, 11 May 1919; page 1; the identical stories were reported with improved text in The State [Columbia, SC], 11 May 1919, page 1, “Six Dead In Clash”; The State [Columbia, SC], 12 May 1919, page 1, “Charleston Riot Costs Two Lives.”

[16] Charleston News and Courier, 11 May 1919, page 1.

[17] Charleston News and Courier, 11 May 1919, page 1.

[18] The testimony of James Freyer (not Frayer) is part of the Navy report discussed in Krugler, 1919, chapter 2; Charleston News and Courier, 12 May 1919, page 8. Charleston News and Courier, 11 May 1919, page 1.

[19] Charleston News and Courier, 11 May 1919, page 1.

[20] Krugler, 1919, chapter 2. Charleston News and Courier, 17 May 1919, page 10.

[21] Charleston Evening Post, 12 May 1919, page 9; Charleston News and Courier, 11 May 1919, page 1; Charleston News and Courier, 16 May 1919, page 10.

[22] See Charleston News and Courier, 11 May 1919, page 1; Charleston News and Courier, 12 May 1919, page 8; Charleston Evening Post, 12 May 1919, page 9.

[23] These details were gleaned from the City of Charleston’s Return of Deaths and microfilm copies of Charleston County Death Certificates, both resources held at CCPL. The name of James Tolbert’s wife appears next to his name in Walsh’s 1919 Directory, page 732.

[24] Krugler, 1919, chapter 2.

[25] Charleston News and Courier, 12 May 1919, page 8.

[26] Charleston News and Courier, May 13, 1919; page 12.

[27] Charleston Evening Post, 15 May 1919, page 9, “Verdicts Found in Riot Cases”; Charleston News and Courier, 16 May 1919, page 10, “Verdict Returned on Street Rioting.”

[28] Krugler, 1919, chapter 8; Charleston News and Courier, 21 May 1919, page 10, “Bluejackets on Liberty.”

[29] The State [Columbia, S.C.], 12 May 1919, page 4, “Not a Charlestonians’ Row.”

PREVIOUS: Searching for the History of the Gaillard Graves

NEXT: The Rise of Streetcars and Trolleys in Charleston

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments