Dining and Drinking in Charleston Before the Food and Beverage Industry

Processing Request

Processing Request

Have you heard this one? A stranger walks into a time machine and says, “Take me back to a place and time in historic Charleston where I can buy a meal and a drink without having to toil over a hot stove.” The operator turns to the camera and says with a smirk, “Dinner in ye olde Charles Towne—do you want fries with that?” But seriously, folks, the retail food and beverage options available in our community’s past included far more variety than shrimp-and-grits and other familiar traditions. In fact, the menu is overwhelmingly diverse, so today we’ll whet our appetite with a starter course of bite-sized samples of the big picture.

The current restrictions on travel and social distance have generated ample supplies of anxiety and frustration for most of us, and have curtailed our economy in ways we never thought possible. Among those most directly impacted by the current crisis is that sphere of commerce generally known as the “food and beverage industry.” The “F and B,” as insiders call it, is part of the larger “service sector” of our economy, composed of a wide variety of businesses that provide consumable goods and related services to paying customers. Culturally as well as economically, the food and beverage industry is distinct from the allied fields of food production and food distribution, of course, both of which seem to be weathering the crisis in good form so far. We are fortunate that most people are able to procure sufficient food at this time, which they can cook and consume at home without the risk of infection. On the other hand, the current crisis has nearly decimated the business of selling prepared, ready-to-eat foods and beverages to paying customers—not just in the Charleston area, but around the world.

Many people in the food and beverage industry are struggling to adapt to the current crisis by brainstorming about new methods and service models of continuing their businesses. I’m not an F&B insider of course, but, as a public historian, I try to use my skills to uncover information about our community’s past that might provide some inspiration for our present world. Turning my attention to the current landscape of shuttered restaurants and bars recently, I asked myself a few simple questions: Is there anything in Charleston’s own history that might provide some inspiration to folks in the modern food and beverage industry? Are there any sort of long-forgotten practices, customs, or historical adaptations that might prove useful in light of the present crisis? I began my search for answers by trolling through my storehouse of research notes about a wide variety of Charleston topics accumulated over the past twenty-odd years. Then I turned to the online database of early Charleston newspapers to which CCPL provides digital access (America’s Historical Newspapers) and did a bit of fresh research. Following a long deep dive into the materials, I think I’ve found some pretty cool stuff that Charleston foodies will enjoy. Before I launch into the details, however, I want to establish a frame of reference and articulate the necessary caveats.

Many people in the food and beverage industry are struggling to adapt to the current crisis by brainstorming about new methods and service models of continuing their businesses. I’m not an F&B insider of course, but, as a public historian, I try to use my skills to uncover information about our community’s past that might provide some inspiration for our present world. Turning my attention to the current landscape of shuttered restaurants and bars recently, I asked myself a few simple questions: Is there anything in Charleston’s own history that might provide some inspiration to folks in the modern food and beverage industry? Are there any sort of long-forgotten practices, customs, or historical adaptations that might prove useful in light of the present crisis? I began my search for answers by trolling through my storehouse of research notes about a wide variety of Charleston topics accumulated over the past twenty-odd years. Then I turned to the online database of early Charleston newspapers to which CCPL provides digital access (America’s Historical Newspapers) and did a bit of fresh research. Following a long deep dive into the materials, I think I’ve found some pretty cool stuff that Charleston foodies will enjoy. Before I launch into the details, however, I want to establish a frame of reference and articulate the necessary caveats.

My purpose here is to identify the various historical methods of retailing prepared food to paying customers in early Charleston. Keep in mind that the retail food and beverage industry—past and present—forms the tail end of a long chain of related activities leading from farm to table. One could certainly devote a comparable amount of attention to the local histories of raising and cultivating various kinds of foods, transporting those foods from farm to market, the local marketing of raw foodstuffs, and then the art of preparing ingredients for consumption. I have a ton of data on some of those activities, and in many aspects I’m happy to defer to the expertise of other researchers—especially when it comes to recipes and cooking. For the moment, let’s postpone those conversations for another time.

Let’s also recognize that the retailing of prepared food is now and has always been largely an urban phenomenon. People living in sparsely-populated rural areas in the past enjoyed far fewer opportunities to purchase or barter for ready-to-eat meals than their urban counterparts. For this reason, rural fairs, like the ones once held at Ashley Ferry, Radnor, Wiltown, and Childsbury or Strawberry in colonial times, were popular occasions during which vendors sold prepared food to the assembled crowds. There are many, many restaurants and bars in rural and suburban areas of greater Charleston today, of course, but most of these businesses depend heavily on a steady stream of automobile traffic. When quarantine limits our mobility, our cultural habits revert to a pre-automobile mode of life.

In the deep history of urban Charleston, just as today, there were lots of dining options available to residents and visitors, but our ability to study those past options is constrained by the paucity of written documents. All of our forebearers here in Charleston ate meals every day, of course, but eating is generally such a mundane activity that most people don’t write descriptions of their dining habits. Descriptions of cooking and ingredients and recipes are interesting branches of this topic, but I’m narrowing my focus to documentary evidence of the commerce of serving food and drink to paying customers. Some of the best information we have about the food and beverage industry in early Charleston appears in the local newspapers that commenced in Charleston in 1732. Here we find advertisements for services, descriptions of feasts given on special occasions, and small anecdotes about eating and drinking within essays about a wide variety of local news topics. But the newspapers were created for and read by a relatively narrow sphere of affluent, literate people. Those parts of the food and beverage industry intended for less-affluent people were not necessarily described in the newspapers. Consequently, we have very little evidence about the early food commerce related to folks at the lower end of the socio-economic scale. Like today, we might assume that poor people did not “dine out” very frequently, but sometimes there was no choice. People laboring outside their respective residences did not necessarily have the luxury of time to return home in the middle of the workday to prepare or eat a meal.

Despite these research challenges, the high value of the topic makes it worth the effort to dig into local archives for surviving evidence. Let’s begin by using our imagination to ponder the practical realities of Charleston’s early food and beverage scene. We might consider the practice of dining at home with family and friends as a sort of baseline, normal routine, while purchasing food prepared by others outside the home might be a less frequent activity. If one did not prepare one’s own food, what were the dining options in the distant past? We can begin to answer that historical question by considering the present. Forgetting, for the moment, about the current restrictions caused by the pandemic, let’s make a quick review the modern restaurant business. If you’re willing to pay someone to prepare food for you today, what are your options? First, you could stay at home while someone brings a meal to your door, or comes into your home to prepare it for you. Second, you could leave your home and travel to a commercial establishment, pick up ready-made food, and take it home to eat. Third, while away from your home, you might purchase food from a mobile vendor and consume your meal in a public place or on the go. Finally, you might travel to an eating establishment and enjoy your meal right there on the premises, in the company of other diners.

Despite these research challenges, the high value of the topic makes it worth the effort to dig into local archives for surviving evidence. Let’s begin by using our imagination to ponder the practical realities of Charleston’s early food and beverage scene. We might consider the practice of dining at home with family and friends as a sort of baseline, normal routine, while purchasing food prepared by others outside the home might be a less frequent activity. If one did not prepare one’s own food, what were the dining options in the distant past? We can begin to answer that historical question by considering the present. Forgetting, for the moment, about the current restrictions caused by the pandemic, let’s make a quick review the modern restaurant business. If you’re willing to pay someone to prepare food for you today, what are your options? First, you could stay at home while someone brings a meal to your door, or comes into your home to prepare it for you. Second, you could leave your home and travel to a commercial establishment, pick up ready-made food, and take it home to eat. Third, while away from your home, you might purchase food from a mobile vendor and consume your meal in a public place or on the go. Finally, you might travel to an eating establishment and enjoy your meal right there on the premises, in the company of other diners.

Unless you’re a big history nerd like me, you might be surprised to learn that all four of these modern dining options have existed for many centuries, and have been available in Charleston since the earliest days of the town. In fact, I’ve found enough local information about each of these topics that I’ve decided to divide them into a series of separate programs. For the moment, I’d like to share with you four bite-sized summaries to give you a flavor of the upcoming courses. To impose some order on this historical bill-of-fare, I’ll describe them in order of ascending complexity or sophistication: ambulatory food, take-away food (and drink), delivered meals, and on-premises drinking and dining.

Ambulatory food is generally the least complicated sort of fare. It might be something raw or minimally unprocessed, like peanuts, oranges, honey, or fresh shrimp, or it might be something ready to eat like a pastry, ice cream, or a plate of boiled shrimp or steamed oysters. From Charleston’s earliest days to the middle of the twentieth century, ambulatory food sellers known as “hucksters” (or “huxters”) plied the city streets, some with baskets of food balanced on their heads while others pushed small wooden carts of comestibles. The hucksters frequently cried out to the public as they walked, chirping melodious advertising slogans to entice customers on the go. The city’s food markets (in different locations at different periods in our history) always formed their home base, and the ambulatory hucksters—including both men and women—generally ranged through the city’s most populous streets in search of business. You’ll recognize this phenomenon, of course, if you remember that George Gershwin included the honey-man, the crab-man, and the strawberry-woman in the score of Porgy and Bess as a way to infuse his opera with a bit of real Charleston flavor.

The concept of take-out or take-away food and drink has existed as long as there were hungry people who didn’t feel like cooking. In Charleston, this sort of activity is one of the hardest to document because it didn’t rely on advertising or expensive infrastructure. By combining a handful of surviving local clues with facts about this sort of activity in other historic communities, and in the present, however, we can reconstruct a bit of the take-out culture of early Charleston. Entrepreneurs with cooking equipment in their own homes sold food to passing pedestrians without requiring customers to enter the premises. Part of the evidence for this historic practice involves a once-common but now forgotten architectural feature called a “stall board,” which transformed an open window into a platform for contact-free business. Laborers with limited time for a mid-day meal could bring their own tin cup or lunch pail to such an establishment and take away a serving of ale and a bowl of soup. Some vendors used illegal outdoor fires to cook market goods on the fly. More sophisticated vendors with larger kitchens and staff were able to offer complete meals for entire families, ready for pick up on short notice.

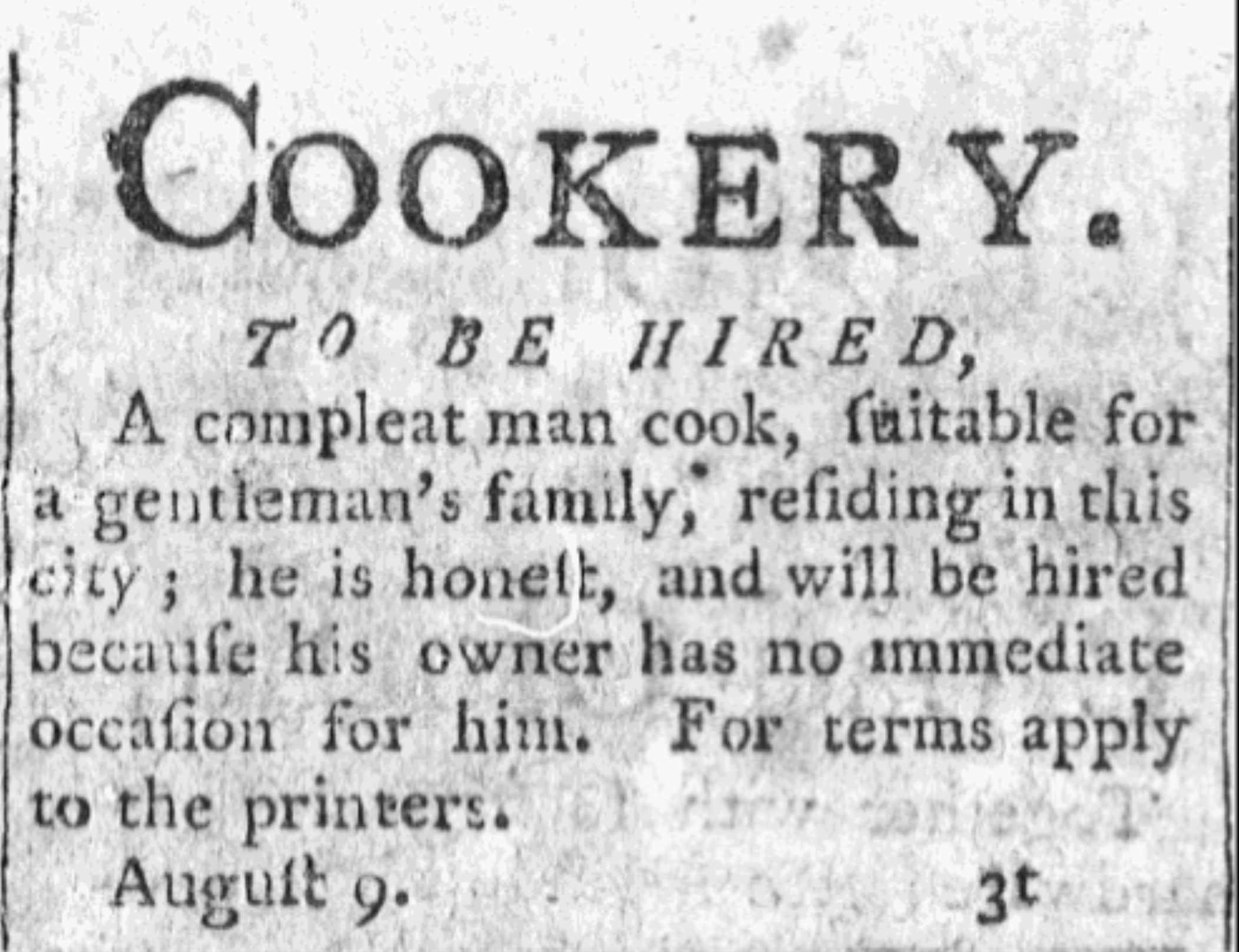

Food delivery was part of the Charleston dining scene long before the arrival of pizza and Uber, but the clientele for such services was much smaller in the past. Before the proliferation of the automobile in the twentieth century made food delivery a relatively quick and cheap option, only the most affluent customers could snap their fingers and summon ready-made food to their table. Where there’s a market, however, there’s always means to commerce. The restauranteurs of early Charleston could dispatch meals to a client’s house for a handsome fee, or send a cook and staff to prepare and serve a feast within the customer’s own kitchen. Adam Pryor, for example, came from London to Charleston in 1786 and offered to “perform the art of cookery in all its variety” for the ladies and gentlemen of Charleston. In the distant past as today, hungry homeowners could also hire chefs of known abilities to cater domestic feasts for a private audience. Prior to 1865, the owners of skilled enslaved cooks rented their culinary services to paying customers in Charleston’s rarified world of high cuisine.

Food delivery was part of the Charleston dining scene long before the arrival of pizza and Uber, but the clientele for such services was much smaller in the past. Before the proliferation of the automobile in the twentieth century made food delivery a relatively quick and cheap option, only the most affluent customers could snap their fingers and summon ready-made food to their table. Where there’s a market, however, there’s always means to commerce. The restauranteurs of early Charleston could dispatch meals to a client’s house for a handsome fee, or send a cook and staff to prepare and serve a feast within the customer’s own kitchen. Adam Pryor, for example, came from London to Charleston in 1786 and offered to “perform the art of cookery in all its variety” for the ladies and gentlemen of Charleston. In the distant past as today, hungry homeowners could also hire chefs of known abilities to cater domestic feasts for a private audience. Prior to 1865, the owners of skilled enslaved cooks rented their culinary services to paying customers in Charleston’s rarified world of high cuisine.

The business of inviting customers into a facility to consume a meal or a drink on the premises is an ancient practice that has evolved far beyond its humble beginnings. The basic concepts behind the modern restaurant and bar existed in early Charleston, but it wasn’t called a restaurant or a bar and we might not recognize it as place of culinary business. Here our modern vocabulary fails, and we have to resort to an eighteenth-century dictionary to identify the clues. The landscape of eighteenth-century Charleston, for example, was littered with taverns, inns, public houses, victualing houses, houses of entertainment, and ordinaries. On King Street alone during the late colonial-era, customers lodged and ate at the sign of the Crown, the Bear, the Peacock, the Seven Stars, The Cross Keys, the Buck, the Sloop, the White Horse, the Bay Horse, the Black Horse, the Golden Horse, the Horse and Chair, the Horse and Jockey, and the Horse Centienel. These ancient English terms denoted facilities that offered meals of varying degrees of sophistication to paying customers who sat at tables and consumed their fare on site. As global commerce and communication increased in the early nineteenth century, new dining practices and vocabulary came across the ocean to transform Charleston’s culinary scene. Saloons, hotels, and restaurants—products of post-Revolutionary France—gradually supplanted the old English taverns, inns, and ordinaries. This transition involved more than just a new vocabulary. The new manner of seating, the variety of the menu, and the introduction of a la carte dining transformed the expectations of customers. The roots of Charleston’s restaurant business were far simpler and streamlined than the French-infused model offered to twenty-first-century customers.

Within each of these four categories of food and beverage service in early Charleston we find a wide range of variations influenced by a number of factors. For example, the modes of food presentation or delivery depended on the type of food being sold—whether it be a complete meal or something like a hand-held pastry, a loaf of bread, a plate of seafood, or a mug of porter. Long before the advent of modern tourism in the twentieth century, Charleston’s food and beverage industry also presented different options for local residents and for visiting “strangers,” as tourists were once called. Dining and drinking outside one’s home were also male-dominated activities for most of Charleston’s history. The inclusion of women as both business proprietors and customers form an interesting part of the evolving story of restaurants and bars from colonial times to the present. Furthermore, we can never forget that food and beverage services in Charleston’s past were always segregated—to one degree or another—by race and class. Wealthier white folks in this community have always had the option to dine in venues separate and distinct from the less affluent laboring classes, and venues serving food and beverages to the laboring masses generally made distinctions between white and black customers until the relatively recent past. Civil Rights protests over dining segregation made headlines here during the 1960s, just as they did in the spring of 1870 during Charleston’s troubled era of Reconstruction.

In the coming weeks, I’d like to dish out a series of deeper dives into each of these topics and try to shed more light on the roots of Charleston’s food and beverage industry. Whether you’re a gourmand curious about the eating habits of past generations, an archaeologist contemplating some curious artifact deposited by an ancient diner, or a novelist trying to reimagine the city’s cultural landscape of specific era, I think you’ll enjoy the upcoming treats. In the meantime, I’ll set a place for you at the table.

In the coming weeks, I’d like to dish out a series of deeper dives into each of these topics and try to shed more light on the roots of Charleston’s food and beverage industry. Whether you’re a gourmand curious about the eating habits of past generations, an archaeologist contemplating some curious artifact deposited by an ancient diner, or a novelist trying to reimagine the city’s cultural landscape of specific era, I think you’ll enjoy the upcoming treats. In the meantime, I’ll set a place for you at the table.

PREVIOUS: A Moderate Trot through the History of Street Speed

NEXT: Hucksters’ Paradise: Mobile Food in Urban Charleston, Part 1

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments