The Fall of the Urban Vultures

Processing Request

Processing Request

Today we’re going to travel back in Lowcountry natural history to continue and conclude our discussion of vultures in urban Charleston. In the previous episode, I talked about the presence of these scavenging birds in the early days of Charleston, especially their long relationship with the butchers of Charleston. From the opening of the new Centre Market in Market Street in August 1807, black vultures earned a level of government protection because they provided an important public service: the birds ate all of the animal scraps and leftovers cast aside by the butchers who plied their trade in the city’s busy food market. Numerous nineteenth-century visitors to the Charleston market remarked on the city’s strange relationship with the vultures, and today this story is still part of every tour guide’s standard repertoire. But in Market Street today you’ll find a population of zero vultures, or “turkey buzzards,” as people commonly called them. So, what happened to the big black birds? When, how, and why were vultures banished from the city? The answers to these questions can be found in archival records like newspapers, diaries, and the records of the city government, scattered over a period of nearly half a century. So, set your mental time machines back to post-Civil-War Charleston, and let’s take a tour of the evidence.

In the last episode, we heard from several nineteenth-century visitors to Charleston who remarked on the somewhat bizarre reciprocal relationship between vultures and the city government. There was once a fine levied on anyone who interrupted the numerous vultures in crowded Market Street, where they kept the ground free of meat scraps. As late as the 1870s, there were members of the local community who seemed to take pride in this old tradition and celebrated “B’rer Buzzard” as an honorary member of the home team.

As northern tourism to Charleston increased in the years after the Civil War, however, a change began to take place. In the late 1860s, 1870s, and 1880s, the science of “germ theory” was a relatively novel phenomenon, and new ideas linking illness and bacteria were beginning to create a revolution in public hygiene. Cleanliness had a direct correlation to healthiness and all that was positive and modern. Dirt, filth, waste, and offal, on the other hand, became increasingly associated with disease and all that was negative and backward. In the wake of visitors from more “modern” cities up north and out west, many of whom were bemused by poor old backwards Charleston, the city grew increasingly self-conscious about its traditional relationship with those natural scavengers, the black vultures.

I’ll give you one good example of the local backlash against the vultures, or buzzards as they were commonly called. On the 18th of August 1881, an anonymous correspondent to the Charleston News and Courier presented a well-reasoned argument against the bird and its ancient, protected status as a necessary evil in the city’s marketplace. It’s a rather wordy narrative, but I think it merits a full reading:

“The Charleston Buzzards.

The sacred bird in Charleston is the buzzard, not for any majesty of mien or dignity of flight, but because of its supposed efficiency as a scavenger. There is not in the animal creation a more disgusting bird than the buzzard. It is associated in idea with filth and corruption. Where decay and foulness unspeakable are found, there will the buzzard be. Unhappily the haunt of the buzzard in Charleston is the otherwise clean and sightly market. The one place which should be without spot or blemish, and is really admirably kept, is defiled by the presence of loathsome buzzards. These birds swoop about the streets along side the market, wrangling over morsels of meat or offal, and when market hours are over they do not confine themselves to the streets. The thought that they can drag themselves over the [butchers’] stalls is not conducive to appetite, especially in warm weather.

Of what use are the buzzards? They swallow gluttonously the scraps from the market, and so keep the streets clean. But there is no necessity for throwing offal into the streets, in order that buzzards shall play scavenger. When the butchers gather up their offal and rubbish as other citizens are obliged to do, there will be no need of scavengers, and the buzzards will find another roost. And if no offal is now thrown out and no scavenger is needed, why are the buzzards held in reverence?

There is a tradition that anyone who molests one of the buzzards in Charleston Market will be fined five dollars. Nobody has been fined in this way these many years. Why the fine, if ever authorized, was ever imposed, no one has vouchsafed to explain. The presumption is that the buzzards are deemed venerable because they have haunted the market [since] time out of mind. They are, so to speak, a landmark. If this is a reason for not interfering with them, there was good reason for objecting to such innovations as street care, gas and water-works. Change for the sake of change is not particularly laudable. Change which is in the direction of improvement is always to be desired. As long as the buzzards make Market Street a free-lunch stand for the whole buzzard family, the Market will not and cannot be the sweet and toothsome place that the man of good appetite and digestion, on dinner bent, naturally desires.

It may be that the buzzards will not be driven away, because of the supposition that the streets cannot be kept clean without them. In that event it is not worthwhile to stop at half-measures. There should be no discrimination in favor of butchers. Let every house-holders be at liberty to throw garbage into the streets, and then the City Council can turn loose the gentlemanly pig to make there an honest and economical living.”

At the time of this editorial, in late 1881, however, the government of the City of Charleston was not in a position to completely overhaul its sanitation system. Since the 1750s, the local government had provided a weekly curbside garbage collection service, using horse-drawn carts to carry household trash to an open dump on the northern fringes of the town. The system was slow and inefficient, but it also gradually filled the marshlands and creeks on the narrow peninsula and created new, taxable real estate. In the immediate post-Civil-War era, there was no money to purchase new equipment or to build a new-fangled garbage incinerator, nor was there a convenient supply of extra dirt to bury the city’s garbage. Nevertheless, the city took a small step toward modernity by making a small effort to shoo away the vultures. In May of 1883, a local resident named Jacob Schirmer Jr. recorded the following anecdote in his personal diary, which you’ll find at the South Carolina Historical Society: “The Charleston buzzards—long under the protection of our City Fathers are now being shot around the market by their old protectors. ‘One by one the landmarks fall.’”

Charleston’s forlorn condition at the dawn of the twentieth century was ably captured by a visiting reporter for the New York Times. In a long article published on the 7th of January 1900, the reporter made the following remarkably blunt observations about our city:

“Charleston admits, reluctantly and sadly, that it is not an up-to-date city. Many causes, which cannot be enumerated here, have contributed to the retarding of that progress for which it yearns—to which its intelligence, disposition to enterprise, its cultivated sympathy with the best in all directions have impelled it—while other Southern cities have advanced. Circumstances have made it a staid city, with a large number of citizens who are apt to take their pleasures sadly, as if the enjoyment of the trivial, at the sacrifice of dignity, was verging on the criminal.”

The reporter then turned his wry attention on “Charleston’s Buzzard,” who became the butt of a joke between city leaders and the visiting members of New York’s Gridiron Club:

“Charleston has not yet provided itself with the appliances for city sanitation that will drive away the buzzards that act as scavengers. One of the jokes arranged by Charleston at the expense of the Gridiron Club was the capture out in the country—there is a fine of $5 for killing a city buzzard—of one of these ravenous and awkward birds. With a graceful speech he was transferred. The givers got a speech, a short one only, in return. ‘I am surprised,’ said President West [of the Gridiron Club], ‘that Charleston should venture to part with this harmless, necessary bird, and yet I am delighted. Only in a city so thoroughly dead as Charleston would you expect to find a buzzard; only a dead city that was sensible of a reawakening to life would be willing to let its buzzards go. We shall take it away to a place where, with lack of employment and a supply of carion [sic], it will surely die, while we are listening for reports of Charleston’s complete revival.’ . . . E. G. D.”

Despite the lighthearted banter about Charleston’s dirty buzzards, city leaders were evidently feeling the sting of embarrassment. Year after year, the city’s chief health officer pushed for more robust trash collection and the erection of a municipal incinerator to burn garbage rather than continue the traditional practice of simply spreading it across the marshlands on the northeast part of town. In 1901, a new naval base opened in what would become North Charleston, and the commercial traffic through the port began to expand. In the spring of 1902 the city hosted the South Carolina Inter-State and West Indian Exposition, which was designed to showcase the region’s commercial amenities and potential. Expecting hordes of visitors that never really materialized, the city of Charleston did a great deal of housecleaning and tried to look its best. So, how did the vultures fare? To answer that question, we’ll turn to a report in The State newspaper, published in Columbia on the 26th of April 1902, titled “Some Side Lights on Old Charleston.” The anonymous reporter noted that many visitors to the Exposition were also visiting the rest of Charleston:

“One of the favorite places for visitors is the market. . . . ‘What has become of the buzzards’ is a question which is heard from many who know of the consideration with which the bird is treated in Charleston. It is a remarkable fact that the buzzards are disappearing. They once flocked in great droves to pick up rejected meats from around the market house, but there are few buzzards to be seen now. It is not only a violation of law, but an offense against the traditions of Charleston for these birds to be harmed. The highly privileged camera fiend is the only one who is permitted to take a shot at them.”

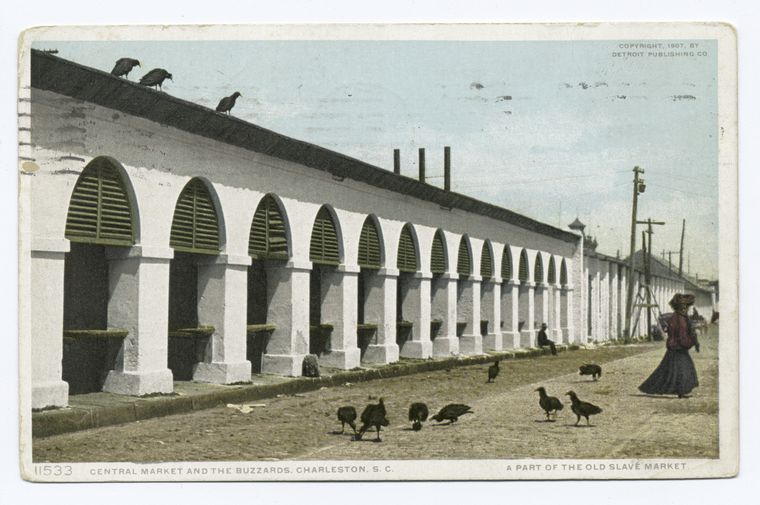

A number of illustrated postcards published around the turn of the twentieth century provide visual evidence that vultures were still a common sight in Market Street, though apparently their numbers were in decline. That decline was made permanent in the summer of 1906, when Charleston’s City Council authorized a series of sweeping public health reforms. The year 1906 was a banner year for such changes, fueled by both the publication of Upton Sinclair’s graphic critique of the meat packing industry, The Jungle, and new Federal laws to regulate food safety across the nation. That June, City Council passed a health ordinance that forced the city’s food industry into the modern age. Meat and milk would now be inspected and graded before sale, and Charleston’s primitive slaughterhouses would be overhauled (eventually). Although not specifically prescribed in this 1906 ordinance, the butchers working in Market Street also faced reform. Later sources inform us that the Commissioners of the Markets, the body of men traditionally appointed to manage the operation of the public market, apparently ordered the butchers to stop throwing meat scraps into Market Street. With that simple change in 1906, the days of the urban vultures were numbered. As soon as the birds figured out that their traditional bounty of free street meat had disappeared, they moved on to greener, or rather browner, pastures.

Just as postcards sold to tourists at the turn of the twentieth century illustrate the presence of vultures in Market Street, other, less familiar sources confirm the presence of vultures in Charleston’s municipal dump during that same era and beyond. As the city expanded northward in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, so too did its open-air dump. In the early decades of the twentieth century, the city dump was located immediately north of Vardell’s Creek, which flows into the Cooper River just north of Cooper Street. Here garbage, including discarded clothing and paper as well as food scraps and animal carcasses, was spread over the surface of the low-lying ground and allowed to fester under the sun and rain. Here also were found flocks of black vultures and poor black women and children, who picked through the filth in search of something valuable, edible, or wearable. In his 1905 book Wild Wings, photographer Herbert K. Job captured the scene with a somber quietness that still evokes pathos more than a century later.

Just as postcards sold to tourists at the turn of the twentieth century illustrate the presence of vultures in Market Street, other, less familiar sources confirm the presence of vultures in Charleston’s municipal dump during that same era and beyond. As the city expanded northward in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, so too did its open-air dump. In the early decades of the twentieth century, the city dump was located immediately north of Vardell’s Creek, which flows into the Cooper River just north of Cooper Street. Here garbage, including discarded clothing and paper as well as food scraps and animal carcasses, was spread over the surface of the low-lying ground and allowed to fester under the sun and rain. Here also were found flocks of black vultures and poor black women and children, who picked through the filth in search of something valuable, edible, or wearable. In his 1905 book Wild Wings, photographer Herbert K. Job captured the scene with a somber quietness that still evokes pathos more than a century later.

Other sources from that era confirm the migration of the birds from Market Street to the city’s dumping ground, where they probably had always maintained a presence. As Charleston continued efforts to modernize, however, even this traditional buzzard buffet was destined to disappear. After many years of contemplation, the city opened a municipal abattoir (a modernized slaughterhouse) in 1912 and opened its first municipal garbage incinerator in 1918. A reporter from The State newspaper was here to witness the incinerator’s opening, and on the last day of May 1918 filed the following brief, buzzard-friendly report:

“After being under construction for several months the municipal incinerator will go into commission in the next few days. It is a large plant, capable of burning 40 tons of refuse daily. It is now practically completed and has been burning test fires this week. The arrival and installation of a pyrometer is the only item lacking in its equipment. One of the Charleston ‘institutions’ that will feel greatly the effect of the ‘swill furnace’ is the time honored and widely known buzzard, which now feasts at the garbage dumps with relish. First the buzzard deserted the central market when the butchers had to put in screens and stop throwing meat scraps into the street and now the dump pile will soon lose its daily contribution and this means further restrictions of ‘B’rer Buzzard’s’ opportunities for good living.”

The buzzards, or vultures, were not the only ones who deserted Charleston’s traditional market in Market Street, however. As corner groceries and modern supermarkets like Piggly Wiggly began to appear in the early years of the twentieth century, most of the human customers also turned their backs on the old city market. In an effort to draw customers back to Market Street, the city government joined forces with market vendors to clean up the old facilities and to launch a public relations campaign. Around 1921 these joint forces published a brief promotional pamphlet imploring customers to come “Back to the Market,” which was now assuredly vulture-free:

“Progressive housekeepers, and men who take a normal interest in their home affairs, will readily appreciate the advantages the market now affords. There is surely a better flavor in food selected personally, a satisfaction in knowing that it is fresh and wholesome and sold in honest measure. And while it may be true that the men and women of former days had more leisure, electric cars and automobiles of modern times make marketing a quick and convenient undertaking. The greeting of friends at the market will be renewed with fresh zest. Only the buzzards, so-called ‘The Charleston Eagles,’ will be forever banished. The day of the scavenger is dead. Modern sanitary measures dedicate the temple anew to the spirit of ‘The Wingless Victory.’”

By the 1920s, vultures were rapidly becoming a rare sight in urban Charleston, due in large part to the enforcement of modern sanitation codes and the burning, rather than surface dumping, of the municipal garbage. (That’s not entirely accurate, however, because the city’s first incinerator, which opened in 1918, proved to be inadequate, inefficient, and unreliable. A few years later the city resumed its traditional practice of spreading garbage across the landscape north of what is now Lee Street, and a new, more reliable incinerator didn’t come online until 1935, but that’s a story for another day.) At any rate, the reign of vulture in urban Charleston was effectively over by 1923, when Mayor John P. Grace took credit for effecting most of the changes that eradicated the familiar birds. Grace served as the city’s chief executive for two four-year terms between 1911 and 1923, and in his final state-of-the-city address (published in the Charleston Year Book of 1923) he looked back to compare the “modern” state of the city with the “primitive” conditions endured at the dawn of the twentieth century:

“Twelve years ago not one single street, except around the Battery, was paved with smooth paving. . . . Life under these conditions was pestiferous. Our streets were noisy, filthy and impassable and those adjoining the public market had the distinction of being the only streets in the land infested by buzzards, seeking the carrion of the market-place thrown to them as scavengers. Far from being ashamed of these buzzards and their whimsical tricks, our ‘best citizens’ took visitors to show off this civic attraction and our newspapers copied articles from magazines upon the subject. What could better express the state of mind of Charleston of that period?

Our market was a disgrace and our food, milk and meat supply a tragedy. The rejected meat of the nation was dumped in Charleston. For our fresh meat supply animals were slaughtered in back yards or at butcher pens within the city limits, where the familiar buzzard was parked on fences. These were the busy buzzards which worked the market down-town until noon and the butcher pens uptown afternoon.”

In short, the municipal campaign to modernize Charleston in the early decades of the twentieth century effectively exiled the indigenous vulture from the city limits. The process of eradication was relatively straightforward—simply ending the human hand-outs in Market Street and in the city dump—but its execution dragged on for years. If you want to see a black vulture (Coragyps atratus) in urban Charleston today, you won’t find a single one in Market Street, or even on the north side of Lee Street. You’ll have to go to 360 Meeting Street, to the Charleston Museum, where they’ve had a handsome specimen on display for many years.

NEXT: The “South Carolina Hymn” of 1807

PREVIOUSLY: The Rise of the Urban Vultures

See more from Charleston Time Machine