The “South Carolina Hymn” of 1807

Processing Request

Processing Request

Let’s travel back in Lowcountry music history to talk about South Carolina’s first state anthem, or at least the state’s first unofficial anthem. I’m talking about a piece of music called “the South Carolina Hymn,” which was written in the summer of 1807 and first performed in Charleston on August 22nd of that year. Following its debut in 1807, “The South Carolina Hymn” became somewhat of a popular hit song in the Lowcountry, and it was performed at patriotic events in our community for several decades. The hymn was never published, however, and it appears to have been forgotten by the time of the Civil War. Several years ago I discovered two manuscript versions of “The South Carolina Hymn” in two local archives, and since then I’ve been trying to raise awareness of our state’s first unofficial anthem. It’s a decent little tune, and the story of its creation is an interesting story as well. Set your time-travelling brain cells for the summer of 1807, and let’s explore the origins of “the South Carolina Hymn.”

(In case you’re interested, I published a shorter, illustrated version of this material in the Spring 2009 issue of Carologue, the quarterly newsletter of the South Carolina Historical Society.)

During the summer of 1807, residents of the South Carolina Lowcountry received news that shocked them from a state of peaceful repose into a flurry of military preparations. A British warship, the HMS Leopard, had been searching for deserters in coastal waters near Norfolk, Virginia, where it attacked and boarded an American frigate, the USS Chesapeake, on the 22nd of June. It was not the first time that a British warship had stopped an American vessel while searching for deserting sailors. In fact, during Britain’s long war with the French Republic in the 1790s and then with Napoleon Bonaparte in the early 1800s, the British Navy was a constant pest to American shipping in the Atlantic Ocean. The British practice of illegally interrupting American commercial shipping in search of deserters created a heavy strain on diplomatic relations between the two nations, and tensions were already near the breaking point in 1807.

That breaking point arrived on the 22nd of June when the HMS Leopard hailed the USS Chesapeake off the coast of Virginia. The Chesapeake respectfully sailed alongside the larger Leopard and received onboard a British officer who said they were searching for deserters. The American captain said there were no British sailors aboard the Chesapeake, and the British officer withdrew. Moments later, the 50-gun Leopard fired a broadside into the unprepared American frigate, and then demanded her to surrender. Crippled by the unexpected attack, the USS Chesapeake was forced to submit, and the HMS Leopard sailed away after kidnapping four sailors.

In the days and weeks following the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair, as it has become known, the news of unprovoked British aggression quickly spread throughout the Atlantic seaboard. Joseph Manigault in Charleston, for example, wrote to his brother, Gabriel, in Philadelphia, that the report of this British aggression had traveled through Charleston “like an electric shock,” inspiring fear that South Carolina’s shipping trade might soon be attacked as well. During the months of July and August 1807, the Charleston newspapers were filled with news and hawkish editorials predicting imminent war with Britain. The city’s martial spirit led to the rapid formation of a number of new volunteer militia units, including the famous Washington Light Infantry that still exists today.

In hindsight, however, we know that the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair of 1807 did not immediately lead to war with Britain. Several years of trade embargoes and diplomatic negotiations ensued, and the U.S. Congress did not formally declare war on our former mother country until June of 1812. Nevertheless, the outburst of patriotic activity during the summer of 1807 alarmed the young nation into a defensive posture. On a more artistic note, this surge of martial spirit was accompanied by the strains of a new tune—South Carolina’s first unofficial state anthem, “The South Carolina Hymn.”

In hindsight, however, we know that the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair of 1807 did not immediately lead to war with Britain. Several years of trade embargoes and diplomatic negotiations ensued, and the U.S. Congress did not formally declare war on our former mother country until June of 1812. Nevertheless, the outburst of patriotic activity during the summer of 1807 alarmed the young nation into a defensive posture. On a more artistic note, this surge of martial spirit was accompanied by the strains of a new tune—South Carolina’s first unofficial state anthem, “The South Carolina Hymn.”

On 17 August 1807, the Charleston City Gazette carried an announcement for the benefit concert of actor-singer Matthew Sully, scheduled for the following evening at Vauxhall Garden, Charleston’s once-popular summer pleasure garden now occupied by the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist between Broad and Queen Streets. Besides the usual fare of vocal and instrumental selections, the newspaper noted that Sully’s performance would include “a new patriotic chant, written by a citizen of Charleston, called ‘The South Carolina Hymn.’” Inclement weather postponed the concert to August 22nd, however, on which date the City Gazette repeated that Mr. Sully’s concert would include the “new patriotic CHAUNT” [sic] called ‘The South Carolina Hymn.’” Less than a week later, Francis Lecat, a French musician living in Charleston since 1793, announced an upcoming concert at Vauxhall Garden to be given as a joint benefit for himself and for the children of the Charleston Orphan House. That concert, as described in the City Gazette of August 27th, included a “Grand Display of Fire-Works” and concluded, “by particular desire, with the South Carolina HYMN, (the words and the music by a native of this city).”

Note that in the aforementioned 1807 advertisements, the tune in question was called both a “hymn” and a “patriotic chaunt,” or song, while I’ve referred to it as an “anthem.” Most people in South Carolina today probably associate the word “hymn” exclusively with religious music, but two centuries ago the word had a more generic meaning. Similarly, the word “anthem” was once also commonly used to describe both simple songs used in religious worship and secular, patriotic songs. The two terms are somewhat interchangeable, and today we don’t think twice about using the term “anthem” to describe secular songs written to celebrate the qualities of various states and nations. The words and music of “the South Carolina Hymn” are definitely more secular and martial rather than sacred, so I don’t think I’m overstepping any semantic boundaries by referring to this composition as an “anthem.” But I digress . . . .

Back to our main story: Following several public performances in the summer of 1807, the “South Carolina Hymn” was heard on a number of civic occasions in subsequent years. It seems to have become a staple of July 4th celebrations in Charleston for decades, and was heard on a number of observances of Washington’s Birthday as well. As late as 1832 the hymn was sung at St. Patrick’s Day feasts, and in 1839 it was heard between toasts during the 100th anniversary of Charleston’s St. George’s Society. Despite its enduring popularity, South Carolina’s first anthem was never published. It might have been lost forever, had it not been found among the archival collections of the South Carolina Historical Society and the Charleston Museum. Since the version at the South Carolina Historical Society is more robust, I’ll focus my comments on that source.

The words and music of the obscure “South Carolina Hymn” are found at the Historical Society in an old manuscript volume of music labeled “Instructions for the Kent Bugle,” the provenance of which is unknown. This small volume begins with several pages containing a handwritten copy of instructions extracted from Johann Bernhard Logier’s book Introduction to the Art of Playing the Kent Bugle, first printed in Dublin in 1813. The “Royal Kent Bugle,” as it was originally called, was patented in Dublin in 1811 by an instrument maker named Joseph Halliday. By adding five finger-keys to the traditional military bugle, Halliday created a more versatile instrument that paved the way for later, mass-produced brass instruments which led to the proliferation of military brass bands. In 1811 Halliday named his new Irish instrument, the Royal Kent bugle, in honor of the Prince Edward, the Duke of Kent, who also held the title of Earl of Dublin.

Following the initial pages devoted to bugle instructions, the remainder of this manuscript volume at the South Carolina Historical Society consists of music and text copied by an unknown individual or individuals. Included are songs for voice and piano, dance tunes for pairs of flutes or violins, and several more familiar patriotic marches, like “Hail Columbia,” which premiered in 1789. Most of the compositions included in this book reflect Charleston’s long-established adherence to British musical tastes, with works by British composers such as Thomas Arne, Thomas Moore, and Michael Kelly, as well as once-popular Continental composers such as Friedrich Schwindl, Jean-Paul-Gilles Martini, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Much of this music included in this volume was composed in the second half of the eighteenth century, but there are clues that suggest the book was compiled over a period of several decades in the early nineteenth century. Marginal notes written in pencil throughout the book indicate that a portion of the pieces were copied from a magazine called The Kaleidoscope, or Literary and Scientific Mirror, which was published weekly in Liverpool between 1818 and 1831. Complicating matters further is the fact that at some point in its early history the book was disbound and several new pages added. The expanded text block was then tightly rebound using several crude metal staples. Through continued use, many of the book’s pages began to break along the gutter of the overly restrictive binding. In 2003, I had the honor of undertaking a complete repair of the book—carefully disassembling it, repairing each page, and then re-sewing the book to more closely approximate its original construction.

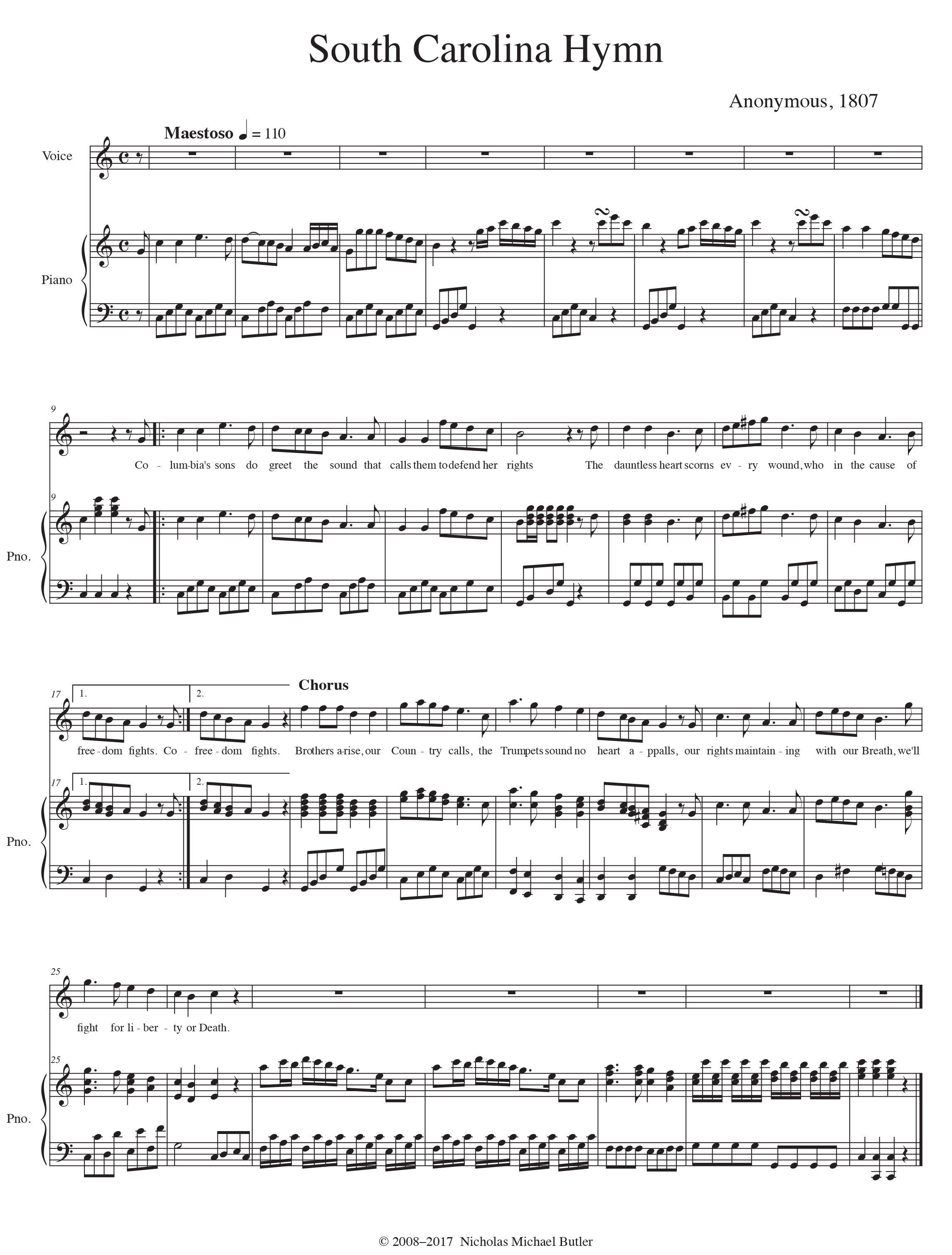

Included among the several pages added to the back of the volume is the “South Carolina Hymn, for the Piano Forte.” This short, march-like composition is presented in the key of C major, in common meter (4/4). The entire hymn consists of thirty measures written in grand staff notation (treble and bass staves joined by a brace): a nine-measure instrumental introduction, an eight-measure measure verse (followed by a repeat sign), an eight-measure chorus, and a five-measure instrumental conclusion.

The lyrics are written directly below the music, and, like many hymns and anthems, the “South Carolina Hymn” employs a verse-chorus structure. In this surviving copy, however, the text of only one verse is included, and a musical sign indicates that it is to be repeated. Other verses may have been sung in the original context, but no vestige of subsequent verses can be found. In a few places the rhythmic pairing of the words to the tune is a bit awkward, but slight adjustments can be made in performance to improve the flow. A rousing, majestic chorus follows the lone verse, and the piece is concluded by a brief but spirited instrumental conclusion.

Verse:

Columbia’s sons do greet the sound

That calls them to defend her rights

The dauntless heart scorns ev’ry wound,

Who in the cause of freedom fights.

Chorus:

Brothers arise, our country calls

The trumpets sound no heart appalls

Our rights maintaining with our breath,

We’ll fight for liberty or death.

Being a bit of a musician myself, I’ve transcribed the hand-written tune into a music notation program on my computer to create a new “edition” of the “South Carolina Hymn.” I copied the notes of both the piano and vocal parts exactly, but I’ve altered the appearance of the beams and rests to make the whole score more legible to a modern musician. The original manuscript lacks a tempo marking, so I’m suggesting a tempo of 110 beats per minute. This tempo might seem a bit slow for a purely instrumental rendition of the tune, but that’s probably as fast as you can comfortably sing the words. But I’d like you to be the judge: I’m attaching a copy of the music score here on the Charleston Time Machine , and you’re welcome to view, listen to, and share the piece.

This little tune might not sound like much, but it’s important to consider that the copy of the “South Carolina Hymn” preserved in manuscript form at the South Carolina Historical Society is likely a simplified arrangement of a more substantial work. The hymn was originally performed more than two hundred years ago at outdoor concerts at Vauxhall Garden, where a band including woodwind and brass instruments regularly performed popular and patriotic music of the day. It seems likely that the composer originally scored the piece for voice and some combination of martial instruments (perhaps including oboes, clarinets, bassoon, French horns, and bugles), and later someone transcribed the extant music for voice and piano as a sort of musical shorthand. I haven’t found any record of the “South Carolina Hymn” being published, but the music and lyrics of the hymn also appear in a similar undated manuscript volume of music in the archive of the Charleston Museum. In that source, however, the hymn is greatly simplified. It’s presented in the key of F major and lacks both the instrumental introduction and conclusion found in the version at the South Carolina Historical Society.

The identity of the composer of South Carolina’s first unofficial state anthem is probably lost forever. According to a description of the tune published in the Charleston City Gazette of 27 August 1807, “the words and the music” of “the South Carolina Hymn” were written “by a native of this city.” The two men associated with the first performances of the hymn, Matthew Sully and Francis Lecat, were both born outside of South Carolina, so we can probably exclude them from the list of possible authors. “The South Carolina Hymn” was probably composed by one of the many gentlemen amateur musicians of Charleston. Two hundred years ago in our community, being a proficient musician was one of the qualities that marked one’s status as member of the gentry class. Lady and gentlemen amateurs might perform music among their family and friends, and perhaps at the exclusive concerts of Charleston’s St. Cecilia Society, but they never performed for money and the newspapers never printed their names when they were publicly associated with such endeavors. In short, it seems the customs of that era purposefully conspired to obscure the identity of the amateur lady or gentlemen who composed this rousing tune.

Despite the mystery surrounding its authorship, the long-forgotten “South Carolina Hymn” deserves to be remembered as part of the cultural heritage of the Palmetto State. Its toe-tapping, tuneful simplicity recalls the “Classical” stylistic era exemplified by composers such as Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven, and its stirring words echo the fearless rhetoric of many generations of patriotic South Carolinians. It survives in an imperfect state, meaning that it would require some musicological reconstruction to restore it to a state more closely resembling its original form, but such work isn’t beyond the skill of musicians right here in our community. Personally, I’d much rather hear the spirited “South Carolina Hymn” of 1807 at a public event than either one of our state’s two “official” anthems, neither of which appeal to my musical or historical sensibilities in the slightest degree. But my opinion counts for nothing. I encourage you to listen to, or to play (on an instrument of your choice) the music of “the South Carolina Hymn” and judge it for yourself. Perhaps you’ll even be inclined to share it with your friends and neighbors. If you do, I encourage you to raise a glass in honor of the events of the summer of 1807, and charge your guests to “Remember the Chesapeake!”

NEXT: What (and Where) is Bee’s Ferry?

PREVIOUSLY: The Fall of the Urban Vultures

See more from Charleston Time Machine