Florence O'Sullivan: South Carolina's Irish Enigma

Processing Request

Processing Request

Florence O’Sullivan was among the first European settlers who came to Carolina in 1670, and he played a significant role in the growth of the colony during the ensuing years. Few details of his life or his personality survive, however, beyond a litany of complaints and accusations made by his English contemporaries. Perhaps by considering O’Sullivan as a stoic Irishman struggling within an Anglocentric framework, we might lift the veil shrouding his enigmatic story and expand a curious narrative from the earliest days of the Carolina Colony.

Besides the island that bears his name, O’Sullivan left no lasting legacy, and he was largely forgotten by subsequent generations. His name and reputation were resuscitated in 1897 by the publication of “The Shaftesbury Papers,” a monograph containing transcriptions of a trove of manuscripts created during the early years of the Carolina settlement. Collected by Anthony Ashley Cooper, the 1st Earl of Shaftesbury (1621–1683), these once-obscure documents contain many previously-unknown details about the people and events that shaped creation of Charleston and the surrounding Lowcountry between the early 1660s and the late 1670s. The name Florence O’Sullivan appears prominently among these records, and their publication at the turn of the twentieth century re-introduced his name and exploits into conversations about the founding of South Carolina.

As numerous scholars and journalist have noted over the past century, the documents transcribed within “The Shaftesbury Papers” do not portray Mr. O’Sullivan in a positive light. In fact, they contain some choice epithets that have been repeated by a host of writers.[1] With so little extant data about this seventeenth-century figure, how do we in the twenty-first century interpret the chorus of complaints and accusations leveled by his contemporaries? Besides searching for overlooked archival sources, my answer begins with the acknowledgement of a rather simple fact: He was Irish rather than English. As such, he was likely the product a culture broken by warfare, hounded from his ancestral lands by the biting realities of dispossession and discrimination. Consider, for example, that the name Florence O’Sullivan was, in a manner of speaking, an assumed identity.

The surname “O’Sullivan” represents the anglicization of the Irish surname Ó Súilleabháin, which identifies the bearer as a male descendant of a man named Súilleabhán. The given name “Florence” did not exist in the Irish language during the seventeenth century, but it represents a common English substitute for several Irish boys’ names. In the case of Mr. Ó Súilleabháin, his first name might have been Fionn (pronounced like “Finn”), or Finín, or perhaps Flaithrí (“flah-ree”). Anglophones of centuries past frequently used the English analog “Florence” as a substitute for these common Irish names.

O’Sullivan was likely born sometime between 1630 and 1640, at which time most of the people bearing the surname Ó Súilleabháin resided in the west of County Cork (Contae Chorcaí) on the south coast of Ireland. No records have yet been found describing his early life, but the Ireland of his youth was a turbulent, miserable place. He would have been just a boy during the brutal Irish Confederate Wars of the 1640s, and, as a teenager, likely witnessed the bloody English reconquest of Ireland under the direction of Oliver Cromwell between 1649 and 1653. In the aftermath of those devastating demographic and religious upheavals, Cromwell’s Protestant followers resumed the earlier English practice of transporting poor Catholic men and women from Ireland to work as servants and laborers the West Indian colony of Barbados, which English adventurers began to colonize in the 1620s. Coincidentally, most of these Irish prisoners were exported through the principal ports of County Cork, Kinsale and Cobh. Those who survived the harsh conditions of colonial servitude in the tropics, often laboring alongside enslaved Africans, could eventually gain the freedom to own land or migrate to another colony.

It is possible that a young man named Flaithrí Ó Súilleabháin survived such an odyssey from Ireland to Barbados during the 1650s, but it’s also possible that he was born in Barbados—the son of poor Irish parents transported to the island during the 1630s. In either case, he was probably raised as a Catholic, and the Irish language (Gaeilge) was likely his native tongue. Furthermore, Protestant Anglophones who encountered this young Ó Súilleabháin might have noticed that he spoke English with the distinctive and occasionally impenetrable accent peculiar to the people of Cork.[2]

The earliest known record of Florence O’Sullivan places him in Barbados in the summer of 1666. According to his own testimony, O’Sullivan was at that moment the captain of an infantry unit that he had recruited using his own money. This was the era of the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–67), and the English governor of Barbados, Francis Willoughby, was assembling an amphibious force to recapture the English portion of the island of St. Kitts from the French. How Captain O’Sullivan acquired the skills and funds to organize a military company is unknown, as is his rationale for supporting a war waged by the Protestant English nation that oppressed the Irish people. He was probably too poor to cling to the luxury of principles. To survive and perhaps advance within a political context that marginalized Irish Catholics, O’Sullivan likely held his tongue, took the king’s shilling to fight under the English flag, and pushed against adversity to escape a bad situation.

The Barbadian squadron organized by Governor Willoughby embarked in late July 1666 and sailed northward across the Caribbean Sea towards St. Kitts. Within days of their departure, however, a tropical hurricane pummeled the English ships and grounded several on the beaches of the French island of Guadeloupe. Captain O’Sullivan was among the shipwrecked men who were obliged to scramble into the jungle and battle with French soldiers for survival. Depleted of provisions and ammunition, the English castaways surrendered in early August. O’Sullivan spent the next eleven months as a prisoner on Guadeloupe before he and other survivors were shipped to France in the summer of 1667. There he was obliged to pay a ransom to secure his release, after which he was transported to England.

In London during the early months of 1668, Captain O’Sullivan was unemployed and penniless. He was obliged to borrow money and live on credit in order to survive in the urban parish of St. Margaret, in the neighborhood of Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament. That April, O’Sullivan and a fellow infantry captain from Barbados submitted petitions to King Charles II, asking for financial assistance. The Irish soldier lamented that he had been attending at Court for five months in hopes of gaining compensation for his military service, but was still “destitute of friends and money.” The King and his councilors agreed to reimburse the value of O’Sullivan’s ransom and to give him a token sum for his allegiance to the Crown, but this royal generosity came with a small catch: O’Sullivan was to be paid in Barbados, where he had performed his military service. In a second petition submitted in July 1668, O’Sullivan complained that he was “in daily danger of imprisonment for debt,” and lacked the resources to arrange passage to Barbados, where a devastating fire had recently leveled the principal city, Bridgetown. King Charles and his Privy Council were not unsympathetic to the Irishman’s case, but they deferred its resolution to an unspecified future date.[3]

The paperwork resolving Captain O’Sullivan’s case has not yet been found, but he apparently received some compensation in late 1668 and maintained his freedom in the English capital. At some point during this year of haunting the government offices in the vicinity of Westminster, he learned of a group of noblemen who were recruiting adventurers to settle a new colony on the mainland of North America. Several of these affluent men, collectively known as the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, were already invested in the Barbadian sugar trade. Through mutual acquaintances, O’Sullivan might have secured an introduction to Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper, the most active and influential of the original Carolina Proprietors.

Details of the conversations between Lord Ashley and Florence O’Sullivan in early 1669 are lost, but we can imagine a plausible but purely hypothetical scenario: Lord Ashley stated that the Lords Proprietors were financing the purchase of ships, provisions, and equipment, and hoped to recruit more than a hundred men and women to cross the Atlantic. Their objective was to create a new settlement in the wilderness of Carolina, where hard work and a strong constitution would be necessary for survival. The expedition required brave men of known merit, capable of performing skilled tasks and able to supervise numerous indentured servants. More specifically, the proposed settlement needed a surveyor who could use the tools of the trade to lay out town lots and plantations and create scaled drawings of large tracts of free land granted to each settler.

Captain O’Sullivan, “destitute of friends and money” and languishing in an unfriendly country, likely embraced the opportunity to acquire free land in a new colony far beyond the pale of English bureaucracy. Ignorant of the tools and techniques of cadastral surveying but fortified by physical strength and determination, O’Sullivan might have bluffed his way into the employment of the Lords Proprietors of Carolina: Sure, he could perform the required survey work, and his military service in Barbados and Guadeloupe provided ample proof of his endurance and military aptitude. Furthermore, if the ships hired for the expedition stopped at Kinsale to recruit Irish servants, O’Sullivan’s knowledge of the local customs and language might also help augment their numbers.

In July 1669, the Lords Proprietors of Carolina presented a commission to “our trusty and wellbeloved Florence O’Sullivan of St. Margaret, Westminster,” to be Surveyor General of the Province of Carolina.[4] At the same time, the Proprietors issued instructions to the commander of the expedition, Colonel Joseph West, ordering him to sail with the “fleete under yor. comand for Kinsaile in Ireland, where you are to endeavor to gett twenty or twenty-five servts. for our proper account.” At that Irish port on the south coast of County Cork, Colonel West was instructed to apply to a pair of local agents “for ye procureing of yor servts., & also use ye assistance of Capt. O’Soolivan.”[5]

Before the frigate Carolina departed from London in early August 1669, O’Sullivan had already recruited eight Irish and English servants to accompany him. The ship arrived at Kinsale at the end of the month, but the appointed agents found it difficult to recruit servants from the local population. The long-standing English practice of kidnapping poor Irish folk and shipping convicts to Barbados made the people of Cork suspicious of any Caribbean invitation. Although representatives of the Carolina expedition ventured into the countryside to canvas for servants, there is no record of Captain O’Sullivan making any contribution to this effort. Joseph West, as leader of the expedition, informed the Proprietors that they procured no servants at Kinsale. A few passengers actually ran away during their two-week anchorage, and the diversion to Ireland in general had been a waste of time and resources.[6]

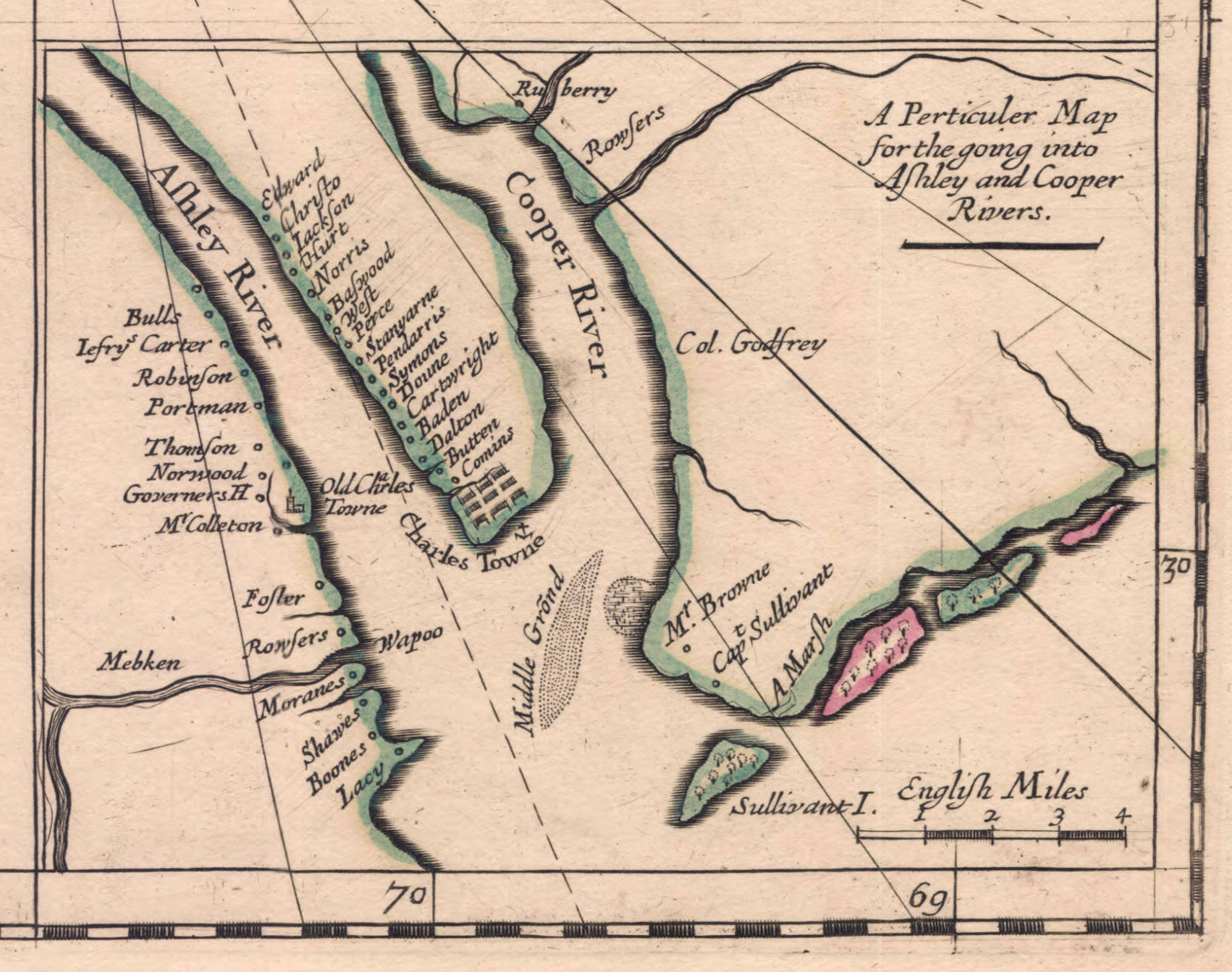

Florence O’Sullivan and his servants were passengers aboard the expedition’s principal vessel, the Carolina, which stopped at Barbados, Nevis, and Bermuda before entering the Ashley River in April 1670. Only one letter written by Captain O’Sullivan in Carolina survives among the Shaftesbury manuscripts now held by the National Archives in London. On the 10th of September 1670, he wrote to Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper to inform him that he and the other settlers were busy “afortifeing ourselves” at Albemarle Point (now Charles Towne Landing State Historic Site). Besides relaying several other unremarkable anecdotes, O’Sullivan asked the Proprietor to “send us a minister qualified according to the church of England.”[7] At least one modern writer has interpreted this phrase to mean that O’Sullivan was a Protestant and a member of the Church of England.[8] I’m not confident of that conclusion, however. I suspect that he might have requested the presence of an Anglican cleric as a sign of loyalty to the English project, in effect telling Lord Ashley what he wanted to hear in order to curry favor with the Lords Proprietors. None of the other evidence of O’Sullivan’s life suggests any interest in the Protestant cause or the practice of religion in general.

O’Sullivan might have had some reason for ingratiating himself to Lord Ashley in the autumn of 1670. At least three fellow settlers at Carolina sent letters to the Lords Proprietors that season complaining of O’Sullivan’s behavior. Stephen Bull, for example, observed that Captain O’Sullivan “doth acte very strangely” and was “a very disscencious troublesome mann in all p’ticulers.”[9] Maurice Mathews, an affluent Welsh settler, famously described O’Sullivan as an “ill natured buggerer of children.”[10] Henry Brayne, captain of the frigate Carolina, complained that O’Sullivan “doth by his absurd language abuse the Governor, Councell and Contry and by his rash and base dealing he hath caused everie one in the Country almost to be his enimie.”[11] All three men, speaking on behalf of their neighbors, informed the Lords Proprietors that Captain O’Sullivan was merely “pretending” to have knowledge of the tools and techniques of surveying. Six months after landing at Albemarle Point, it seems that everyone was dissatisfied with the slow pace of O’Sullivan’s surveys and the inaccuracy of his drawings and field work.

Complaints about the professional abilities and attitude of the Surveyor General continued through the winter and into the spring of 1671. At the first meeting of the Provincial Grand Council of Carolina in August 1671, Captain O’Sullivan informed his superiors that he reached an agreement with his assistant, John Culpeper, to allow Culpeper to keep three-quarters of all surveying fees if he would henceforth perform all of the work. This arrangement dispelled some of the animosity against O’Sullivan, but it did not please everyone. When the Lords Proprietors learned of it a few months later, they cancelled O’Sullivan’s surveying commission and formally promoted Culpeper in his place.[12]

There were other complaints about Florence O’Sullivan in the subsequent months and years, but he ceased to be the target of general derision after his dismissal from the office of Surveyor General. As I suggested earlier, he might have exaggerated his surveying skills during his 1669 interviews with Lord Ashley in London in order to gain passage to a distant colony where he was promised hundreds of acres of free land. Owing to his military experience and innate survival skills, however, O’Sullivan retained some degree of political favor during the ensuing years. In July 1672, he was commissioned as a captain in the nascent South Carolina militia, at which time he was apparently still living at or near Albemarle Point.[13] As a leader of men armed with muskets, broad swords, and hunting knives, O’Sullivan might have participated in some of the raids against neighboring groups of Native Americans, including the Kussoe, Westo, and Stono, whose behavior earned the contempt of the provincial government.

In the autumn of 1672, Governor John Yeamans signed warrants ordering John Culpeper to lay out several large tracts for Florence O’Sullivan, “in such place as you shall be directed by him”—that is to say, at a place chosen by O’Sullivan. The combined total of the warrants was 2,460 acres, but the land was not to be construed as a single package. A large parcel of 1,900 acres represented O’Sullivan’s reward for transporting himself and twelve servants to the colony in the first fleet. A smaller tract of 100 acres was due to his importing another servant in 1671. Sixty acres was reserved “for his present planting nere Charles Towne,” on which land he could reside and grow crops to feed his servants. In addition, the governor ordered Culpeper to lay out 400 acres for Captain O’Sullivan as executor of the estate of a deceased man named Michael Moran, who had arrived on the first fleet from England with his wife and child.[14]

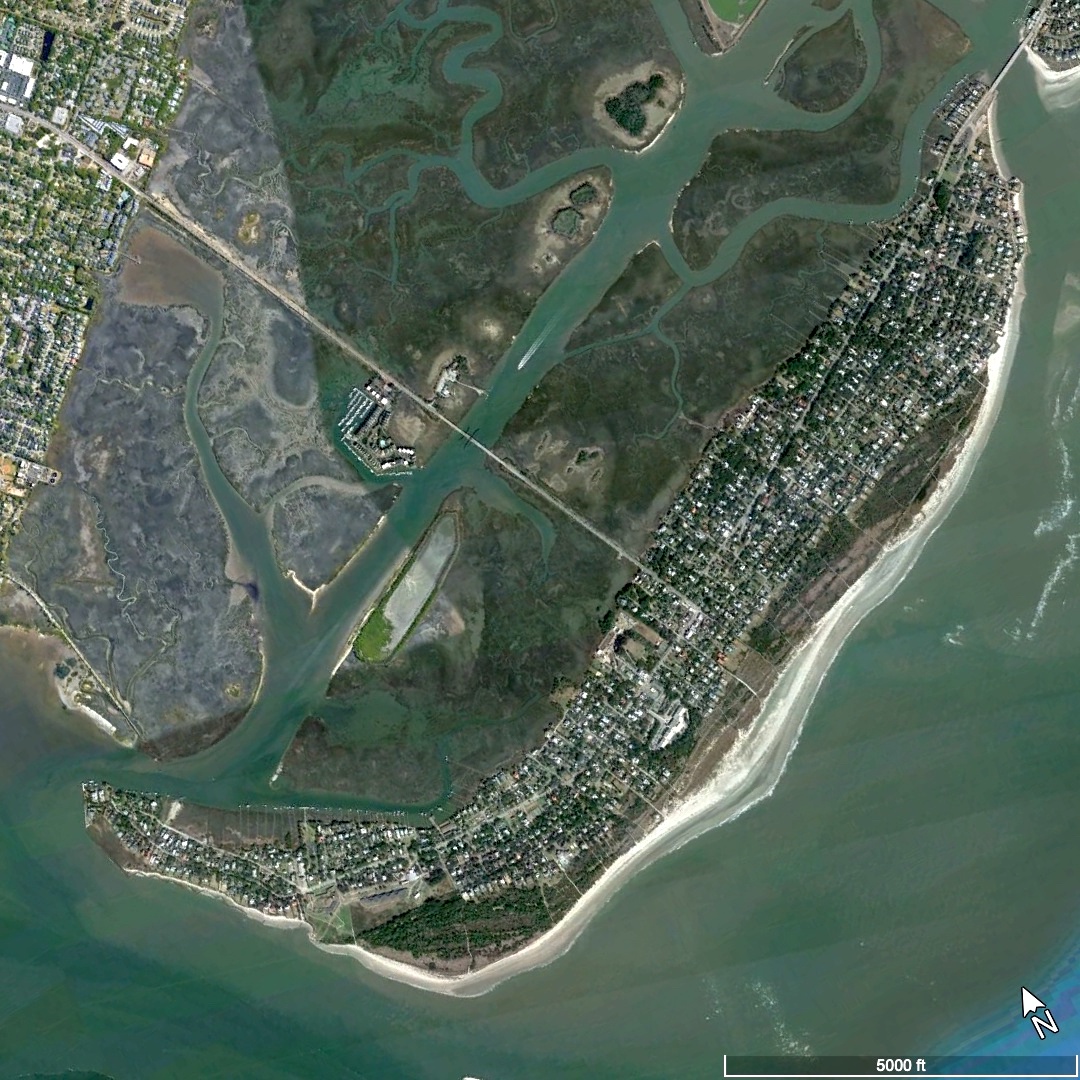

The process of surveying large tracts of land took time and skill, as did the work of creating hand-drawn, hand-colored plats using velum and paints imported from England. Surveyor General Culpeper neglected to survey the land chosen by his former boss, however, and then fled the colony under a cloud of intrigue in the summer of 1673.[15] Despite the long delay of the official survey of his own property during the early 1670s, O’Sullivan had already selected and occupied a choice site on the north side of Charleston Harbor, to the southeast of Shem Creek, in the area that later became known as the village of Mount Pleasant.

At this site during the early 1670s, O’Sullivan might have shared his house with a wife and perhaps started a family of their own. Although no record of a Mrs. O’Sullivan has yet been found, a 1684 document refers to a daughter named Katherine, who might have been a young teenager at that point.[16] Considering O’Sullivan’s reputation for unconventional behavior, it’s possible that he preferred the company of a Native American woman or a perhaps woman of African descent. Their neighbors might have elected to ignore Captain O’Sullivan’s consort in public but condemn them behind their backs. The obscurity of young Katherine in extant records might reflect a similar prejudice that stifled her ability to thrive.

In the late spring of 1674, the Grand Council of Carolina resolved to mount a “great gun” or cannon at “some conven[ien]t place” near the mouth of Charleston Harbor, “to be fired upon the appearance of any shipp or shipps.”[17] The duty of firing the gun was entrusted to Florence O’Sullivan, although he was probably not solely responsible for that labor. As a militia captain, he likely kept track of the necessary supplies of gunpower and tools, but he probably deputized subordinates to help him keep watch over the entrance to the harbor. The Grand Council’s order of May 1674 almost certainly resulted in the placement of a signal cannon on the barrier island that soon became known as Sullivan’s Island, but contemporary confirmation of this supposition does not exist. Captain O’Sullivan never owned or claimed the island in question, so the advent of the name must have stemmed from his public service in that vicinity during the 1670s and early 1680s. The scanty Carolina records of that era simply do not reveal precisely when or why the island acquired its present name.[18]

In the autumn of 1675, Governor Joseph West issued new warrants directing Surveyor General Stephen Wheelwright, formerly one of O’Sullivan’s servants, to admeasure and layout the acreage selected by the Irish captain in the quantities specified several years earlier. Wheelwright’s plat of O’Sullivan’s property, which he completed in early 1677, depicts a row of three adjacent rectangular tracts of different sizes—small, medium, and large. The largest parcel, containing more than 1,800 acres, bounded to the northwest on Shem Creek, to the southeast on a line roughly equivalent to the present line of McCants Drive and Rifle Range Road, and stretched from what is now called Haddrell’s Point northward to the vicinity of Venning Road. To the southeast of this land, a smaller rectangular tract encompassed 400 acres stretching from Charleston Harbor to the vicinity of the present Home Farm Road. To the south east of this middling tract, a smaller parcel of 100 acres encompassed all the remaining high ground at the southeasternmost corner of Mount Pleasant, from what is now Center Street Park northward to the vicinity of Old Village Drive.[19]

In July 1680, O’Sullivan finally received a formal grant confirming his legal ownership of 2,340 acres promised to him nearly eight years earlier.[20] The new Surveyor General, Maurice Mathews, confirmed Mr. Wheelwright’s earlier plat of the captain’s land and made a fresh copy during the winter of 1680/1. His hand-tinted, velum plat, which is now in private hands, depicts a residence and several outbuildings situated within a square enclosure, located in what is now the old village of Mount Pleasant and facing the waters of Charleston Harbor.[21]

Almost immediately after receiving his formal grant, O’Sullivan began selling large parcels of land to his neighbors. In a series of conveyances made between 1681 and 1688, he sold more than 1,500 acres to several parties.[22] By the end of his life, O’Sullivan held only 330 acres adjacent to Shem Creek, just a small fraction of the large tract granted to him. That figure still represents a sizeable estate, but his efforts to divest himself of assets ran counter to the efforts of his contemporaries. Most of the free White settlers who came to South Carolina sought to accumulate as much acreage as possible to enhance their wealth and provide for their heirs. By mortgaging their land to purchase enslaved laborers, many ascended a revolving spiral of expanding wealth. Florence O’Sullivan’s downsizing in the 1680s provides yet another example of his divergence from the contemporary norms. Perhaps he was chronically in debt and needed to liquidate assets to remain solvent. Perhaps he scorned the use of enslaved labor and cultivated far less acreage than his more affluent neighbors.

Having gained a durable legal title to his own property after a decade of frontier struggles, O’Sullivan appears to have withdrawn to a more private life east of the Cooper River. Between 1682 and 1685, he served as an estate administrator for several deceased friends in the vicinity of Charleston.[23] He was perhaps in his 50s at this time, and might have been feeling his own mortality. As the population of the colony expanded, his once prominent role in the militia became less burdensome. In November 1685, for example, South Carolina’s provincial government ratified an act to improve the colony’s defenses “against any hostile invasions and attempts by sea or land.” The act ordered the immediate construction of “one tight small house upon Sullivand’s [sic] Island” and similar structures at other coastal locations to function as lookout stations. Captain O’Sullivan, once in charge of such service, was now one of many lookouts in a less burdensome rotation.[24]

The final days of Florence O’Sullivan are lost to history. He died, most likely at his residence in South Carolina, sometime between 1689 and April of 1692. On the 19th of that month, the Grand Council of South Carolina heard the petition of his daughter, Katherine O’Sullivan, who was apparently in need. The text of her petition does not survive, but we know that the Governor and Councilors assembled at Charleston took pity on the young woman. They decreed that Miss O’Sullivan should “have free lyberty to receive ye charity of all well desposed persons and that Mrs: Mary Cross be the receiver of the said charity & that a briefe [i.e., a subscription list] be drawne signed by ye Secrty to continue for six months and noe longer.”[25]

Later in the year 1692, another Carolinian of Irish extraction, Daniel Carty, bequeathed £5 sterling to “Katherine Sullivan,” whom he identified as the daughter and “orphan” of Florence O’Sullivan.[26] Katherine was still unmarried four years later, when she sold her father’s home to a neighbor. In November 1696, she conveyed to John Barksdale a tract of 330 acres bequeathed to her by her father’s will, which he had drafted on the second day of January, 1680/1. In the text of her sale to Mr. Barksdale, Katherine identified herself as the “sole daughter and heires[s] of Florentia O Sullivan,” and referenced the grant made to her father in the summer of 1680. She described the 330 acres in question as “the last and remaining part of the . . . lands above granted to my said father, and which he dyed possessed of.”[27]

Whether Katherine O’Sullivan remained in the Charleston area or migrated elsewhere is a question not answered by the extant records of colonial South Carolina. Like her father and apparently like her mother, she lived on the fringes of the Anglocentric society that dominated the American colonies in the late seventeenth century. By acknowledging their divergence from the mainstream culture, language, and priorities of their contemporaries, I believe we can better appreciate the life and struggles of people like Florence O’Sullivan. While he might have simply been a cantankerous, belligerent man, we can at least entertain the possibility that he was something far more interesting and sympathetic—a refugee from a broken country, a poor migrant searching for a home. Rather than seeking riches and possessions in the Carolina Colony, perhaps he simply wanted to be left alone, free to express his own beliefs and opinions in the language of his ancestors. Sláinte!

[1] A number of authors have ascribed several negative statements about O’Sullivan to the philosopher John Locke, who served as secretary to Lord Ashley during the 1670s. In reality, however, Locke was merely abstracting letters written by others in Carolina and preparing written summaries of the incoming correspondence for Lord Ashley. For example, numerous writers have quoted a phrase penned by Locke in late 1670, describing O’Sullivan as an “ill natured buggerer of children.” These are not Locke’s words, however, but a brief summary of a longer letter written by Maurice Mathews, the full text of which is now lost. Locke might have met O’Sullivan in London in 1669, but he probably knew little or nothing of the Irishman’s personality before he departed for Carolina. See Langdon Cheves, ed., “The Shaftesbury Papers and Other Records Relating to Carolina and the First Settlement on Ashley River Prior to the Year 1676,” in Collections of the South Carolina Historical Society, volume 5 (Charleston: South Carolina Historical Society, 1897), 248, 259. This 1897 publication is also available online within the digitized collections of HathiTrust.

[2] For an overview of events in Ireland during the period 1641–53, see Micheál Ó Siochrú, God’s Executioner: Oliver Cromwell and the Conquest of Ireland (London: Faber & Faber, 2008).

[3] O’Sullivan’s movements from July 1666 to April 1668 are summarized in the petitions he and Captain John Staplehill submitted to the Crown, now identified as CO 1/22, Nos. 76 and 77, and CO 1/23, No. 12, at the National Archives of the United Kingdom, Kew.

[4] Cheves, “Shaftesbury Papers,” 130–32. This commission is also reprinted in A. S. Salley, ed., Records of the Secretary of the Province and the Register of the Province of South Carolina, 1671–1675 (Columbia: The State Company, for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1944), 8–9. The precise date of O’Sullivan’s 1669 commission is unknown, but it was likely drafted in July; it was recorded in Carolina on 22 October 1671.

[5] Cheves, “Shaftesbury Papers,” 124–25. Note that I have retained the original spelling of the text quoted here and throughout this essay.

[6] Cheves, “Shaftesbury Papers,” 134, 152–55.

[7] Cheves, “Shaftesbury Papers,” 188–90. Note that John Locke’s memoranda of two lost letters from O’Sullivan appear on pp. 348, 389.

[8] Patrick Melvin, “Captain Florence O’Sullivan and the Origins of Carolina,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 76 (October 1975): 244.

[9] Cheves, “Shaftesbury Papers,” 195–96. John Locke abstracted Bull’s complaints about O’Sullivan in a memorandum that appears on pp. 223–24.

[10] Cheves, “Shaftesbury Papers,” 248, 259.

[11] Cheves, “Shaftesbury Papers,” 214–15. John Locke abstracted Brayne’s complaints about O’Sullivan in memoranda that appear on pp. 248, 261.

[12] Salley, Journal of the Grand Council, 1671–1680, 5; Cheves, “Shaftesbury Papers,” 361–62.

[13] Salley, Journal of the Grand Council, 1671–1680, 36, 39–41.

[14] A. S. Salley Jr., ed., Warrants for Lands in South Carolina 1672–1679 (Columbia, S.C.: The State Co., for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1910), 37–38; Michael’s name is spelled “Moran” in Cheves, “Shaftesbury Papers,” 204, 292, but spelled “Moron” in Salley, Warrants for Lands, 1672–1679, 52, 105.

[15] Salley, Warrants for Lands, 1672–1679, 104–5; Salley, Journal of the Grand Council, 1671–1680, 61.

[16] The will of Gabriel Holmes of South Carolina, “gentleman,” dated 22 December 1684, bequeathed £5 to his “loving friend Mrs [sic] Katherine Sullivant [sic] the dau[ghter] of Capt. Florence ô Sullivant [sic]”; see Susan Baldwin Bates and Harriott Cheves Leland, Proprietary Records of South Carolina, Volume 1: Abstracts of the Records of the Secretary of the Province 1675–1695 (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2005), 91.

[17] Cheves, “Shaftesbury Papers,” 450; Salley, Journal of the Grand Council, 1671–1680, 68.

[18] Note that a contemporary copy of John Culpeper’s well-known illustration of the settlement on the Ashley River, which he sent to the Lords Proprietors in 1671, includes the name “Sullivans Island” at the mouth of Charleston Harbor (see MPI 1/13 at the National Archives, Kew). That label might have been added by Lord Ashley or another person several years later, however, as it seems unlikely that Captain O’Sullivan was stationed at that island while there was much work to be done in clearing land, planting provisions, and erecting fortifications at Albemarle Point.

[19] McCrady Plat No. 5803, held by the Charleston County Register of Deeds Office, is an 1868 copy of an earlier plat by Joseph Purcell (died 1807), who made a copy of Stephen Wheelwright’s original plat. Text on the 1868 copy states that Wheelwright’s plat was “certified the 22d day of June 1676/7” (probably representing a mis-transcription of the Julian Calendar date 22 January 1676/7). Note that the three parcels depicted on this plat (measuring 1,804; 400; and 100 acres respectively) form a total of 2,304 acres, which differs from the text of the 1680 grant to O’Sullivan that specified 2,340 acres. Because the latter figure is repeated in multiple contemporary sources, the figure 1,804 in the 1868 copy probably should be 1,840.

[20] South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Register of the Province, Conveyance Books (series 210001), G: 165. This grant is abstracted in Susan Baldwin Bates and Harriott Cheves Leland, Proprietary Records of South Carolina, Volume 2: Abstracts of the Records of the Register of the Province, 1675–1696 (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2006), 84.

[21] Text on the aforementioned 1868 copy of Wheelwright’s 1677 plat of O’Sullivan’s property indicates that it was “countersigned by Mau. Mathews Surv. Genl.” The text of Florence O’Sullivan’s conveyance to John Cottingham, dated 18 February 1680/1 (in SCDAH, Register of the Province, Conveyance Books (series 210001), G: 165–66), refers to a plat of O’Sullivan’s property made by the subsequent Surveyor General, Maurice Mathews, and dated 20 January 1680 (probably meaning 1680/1). Coincidentally, an auction at Charlton Hall Galleries in Columbia, South Carolina, on 10 February 2023, included a faded, hand-colored velum plat by Maurice Mathews, depicting the 2,340 acres specified in the grant to Florence O’Sullivan on 6 July 1680. Low-resolution photographs of the plat can be seen on the Gallery’s website: https://www.charltonhallauctions.com/auction-lot/early-south-carolina-land-grants-and-land-sales-d_D2A47E19BA.

[22] See Florence O’Sullivan to John Cottingham, conveyance of 100 acres, 18 February 1680/1, in SCDAH, Register of the Province, Conveyance Books, G: 165–66; Florence O’Sullivan to Sylvester Cross, conveyance of 673 acres, 24 December 1683, SCDAH, Records of the Surveyor General, Last Resort Book, 1683–1770, pp. 144–46; Daniel Green, 1733 memorials for two tracts of 200 acres each, originally granted to Florence O’Sullivan, SCDAH, Memorial Books (Copy Series), volume 3: 342–43; James Kerr, 1733 memorial for 300 acres originally granted to Florence O’Sullivan, SCDAH, Memorial Books (Copy Series), volume 3, page 411. Note that the total of approximately 1,500 acres probably does not include the 400 acres intended for the heirs of Michael Moran.

[23] See Bates and Leland, Proprietary Records of South Carolina, 1: 54, 57, 73, 74, 77, 78.

[24] Act No. 27, “An Act for the better security of that parte of the Province of Carolina, that lyeth Southward and Westward of Cape Feare, against any hostile invasions and attempts by Sea or Land, which the neighbouring Spaniard or other enemy may make upon the same,” ratified on 23 November 1685, in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 2 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1837), 9–13. Note that this rotating, voluntary service was replaced, at least briefly, by paid watchmen in late 1690; see Act No. 51, “An Act for the raiseing of a fund of money for the maintaining of a watch on Sullivand’s Island,” ratified on 22 December 1690, in Cooper, Statutes at Large, 2: 40–42.

[25] A. S. Salley Jr., ed., Journal of the Grand Council of South Carolina, April 11, 1692–September 26, 1692 (Columbia: The State Company for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1907), 7.

[26] Will of Daniel Carty, dated 5 October 1692, SCDAH, Will Book 1692–93, pages 20–21; WPA transcript volume 1 (1692–93), pp. 5–6.

[27] Katherine O’Sullivan to John Barksdale, conveyance of 330 acres for £40 current money of South Carolina, 20 November 1696, in SCDAH, Records of the Register of the Province, Register Book D (1696–1703), pages 196–98. The will of Florence O’Sullivan does not survive.

PREVIOUSLY: Margaret Daniel: Enterprising Free Woman of Color

NEXT: Blanche Petit Barbot: A Musical Life in Charleston

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments