Hampstead Village: The Historic Heart of Charleston’s East Side

Processing Request

Processing Request

Hampstead Village is a historic neighborhood of downtown Charleston, better known today as the heart of the city’s “East Side.” Created as an affluent suburb in 1769, Hampstead has endured a series of booms and busts over the past two and a half centuries that transformed it into Charleston’s most diverse and densely populated neighborhood. To better understand its present challenges and future potential, we need to take a quick tour of Hampstead’s colorful history and acknowledge its long struggle for dignity and survival.

If you’ve lived in the Charleston area for any length of time, you’re probably familiar with the phrase “East Side.” The precise meaning of that generic moniker is rather flexible and has changed over time, but today it’s generally used to describe the swath of peninsular Charleston bounded on the south by Mary Street, on the west by Meeting Street, on the east by the Cooper River, and continuing northward to about Huger Street. If you’re using Google Maps within this area, your smart phone might say that you’re in Radcliffeborough, or Wraggborough, or Elliottborough, or another one of Charleston’s identifiable historic neighborhoods. But Google is mistaken. Charleston’s generic “East Side” has a deep history and identity that most of the community has forgotten over the past sixty years. The core of the neighborhood is Hampstead Village, and this fall marks the 250th anniversary of its creation.

If this information is news to you, then I hope you’re now pondering the following question: How could Charleston—a community that prides itself on preserving its history and telling its stories to tourists—lose the memory of one of its most historic neighborhoods? The answer is complicated, and even a bit controversial. I had never heard of Hampstead Village when I moved to the “East Side” nearly a decade ago. Once I started digging into its history, however, I found an intriguing story of ambition, destruction, prejudice, and discrimination. On a more positive note, Hampstead’s history is also a legacy of renewal, diversity, and perseverance that everyone in the Charleston area should know and embrace.

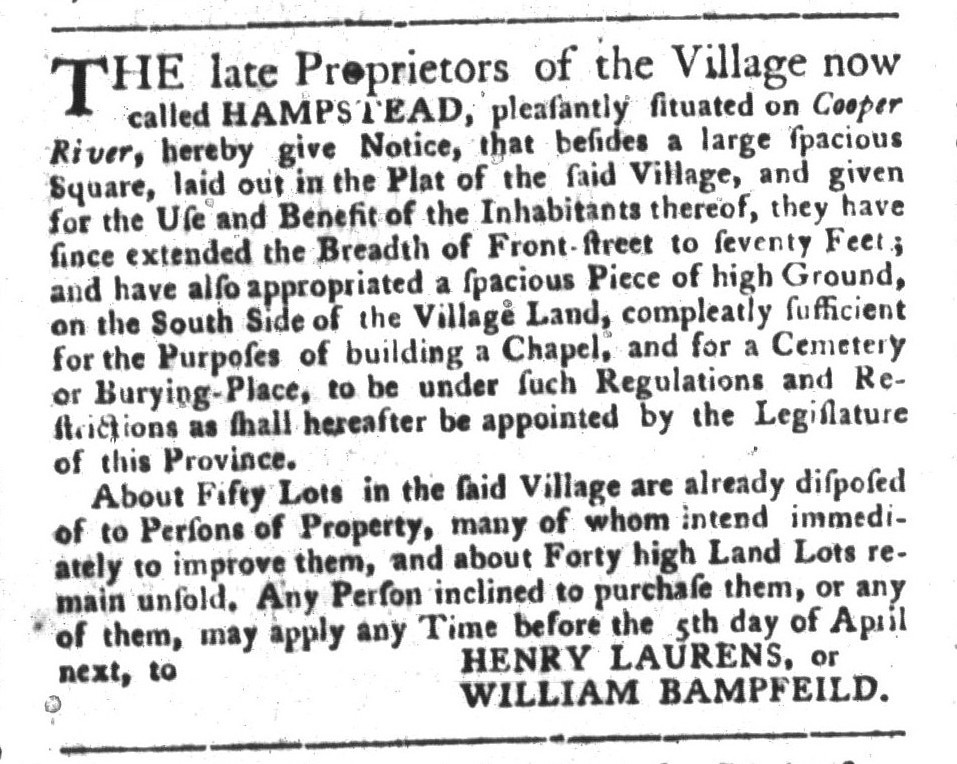

The property that became Hampstead was originally part of a large tract of land located north of urban Charleston, granted first to one Richard Cole in the summer of 1672. Cole’s extensive property, stretching from the Ashley to the Cooper River, was subdivided many times over successive generations, but retained its rural character. By the late 1760s, a large parcel of that land was an empty pasture known as Austin Field, the property of Mr. George Austin. Austin sold his field to Henry Laurens in the spring of 1769, after which Laurens acquired a few more acres to the north from Joseph Wood. Hoping to capitalize on the land’s proximity to the colonial capital, Laurens hired a surveyor to subdivide the tract into building lots and to lay out an orderly grid of streets. In late November, 1769, Laurens began marketing this property the public as a residential development called “the Village of Hampstead.”[1]

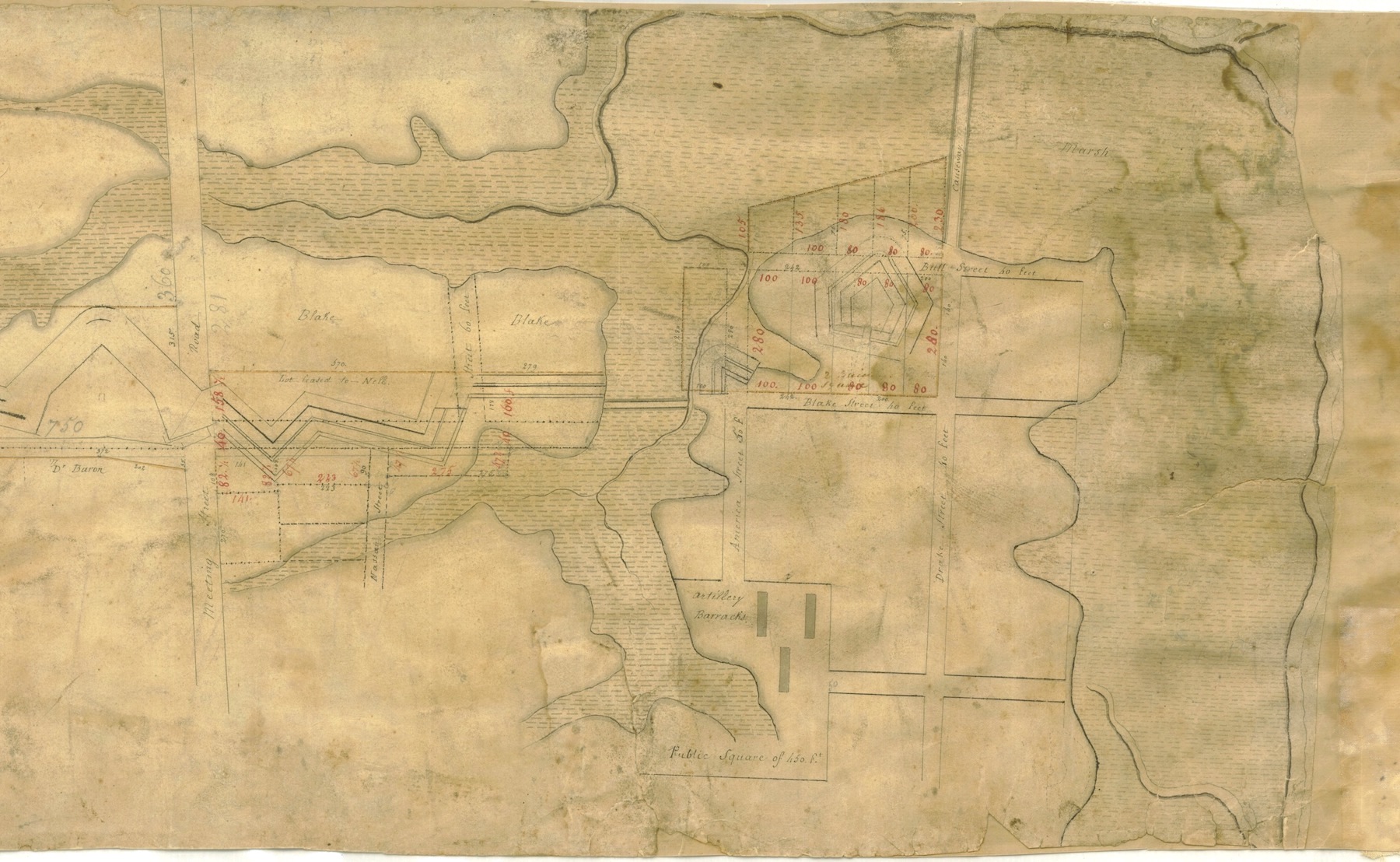

The surveyor’s 1769 plat for the initial subdivision of Hampstead Village shows a tract of around a hundred acres bounded on the east by Town Creek (a branch of the Cooper River), on the west by the broad path leading to Charleston (now King Street), on the north by a “bold creek” (later called Vardell’s Creek now “Grace Bridge Street”), and on the south by the property of the Wragg family that later became Mary Street in Wraggborough. The village included a dozen new streets laid out in a perpendicular grid. Front Street, a broad avenue seventy feet wide and now part of East Bay Street, was the only street named in the 1769 plat of Hampstead.

The surveyor’s 1769 plat for the initial subdivision of Hampstead Village shows a tract of around a hundred acres bounded on the east by Town Creek (a branch of the Cooper River), on the west by the broad path leading to Charleston (now King Street), on the north by a “bold creek” (later called Vardell’s Creek now “Grace Bridge Street”), and on the south by the property of the Wragg family that later became Mary Street in Wraggborough. The village included a dozen new streets laid out in a perpendicular grid. Front Street, a broad avenue seventy feet wide and now part of East Bay Street, was the only street named in the 1769 plat of Hampstead.

The names of the remaining streets appear in property records and newspaper advertisements of the 1770s and are still in use today. Henry Laurens named the central east-west street for Christopher Columbus, and the central north-south street for that mariner’s greatest discovery, America. Both of those principal streets were fifty feet wide, while the remaining nine streets were all forty feet wide. Three streets were named for celebrated men of English history. Drake Street was named for the explorer, Sir Francis Drake. Amherst Street was named for the British commander of North American forces during the recent French and Indian War (1756–1763), General Jeffery Amherst. Wolfe Street (now misspelled “Woolfe”) was named for the fallen hero of the 1759 Battle of Quebec, General James Wolfe. Two of the streets were named for bloodlines of the English royalty. Nassau Street was named for King William III, of the House of Nassau, while Hanover Street was named for the successive King Georges and the House of Hanover. The four remaining streets have more mundane names. Reid Street was named for James Reid, the man who owned property along the southwest corner of Hampstead. Similarly, Blake Street, at the northern edge of the village, bounded on land owned by the Blake family. South Street was apparently so named simply because it marked the southern limit of the village. A short stub of a street at the northeast corner was originally called Bull Street, but later became Cooper Street.

Along these streets the 1769 survey of Hampstead laid out 140 rectangular building lots, each nearly half an acre in size. At the center of the village, at the intersection of Columbus and America Streets, the plan reserved a public square measuring 450 feet on each side, or roughly four and a half acres. According to the initial newspaper advertisements for Hampstead, which appeared in late November 1769, Henry Laurens intended to reserve this “large square . . . in the center of the town for such public uses and purposes, as shall be agreed upon by the first twenty-one purchasers of the lots, or a majority of them.”[2] The early purchasers apparently decided to preserve the square as a public green. Although it’s now four squares instead of one, it’s still known as Hampstead Mall, now the oldest public greenspace in Charleston.

The name “Hampstead” is a reference to one of the most expensive and exclusive suburbs of London, and it provides a clue to Henry Laurens’s vision for his colonial village. Situated just outside the northern boundary of urban Charleston, Hampstead was designed as a suburban enclave for affluent merchants or planters who had business in the town but sought to avoid its noisy, crowded, and dirty streets. Throughout the 1770s, the early investors in the Hampstead development were “persons of property” who built substantial residences on large, half-acre lots. As one early investor described in a 1772 advertisement, his waterfront lots in Hampstead were “well adapted for a retreat either for a gentleman or merchant.”[3]

Henry Laurens’s development scheme for Hampstead progressed rather unevenly in the years immediately after its launch in 1769. As political tensions between Britain and her American colonies increased in the early 1770s, economic growth slowed and men became conservative with their money. The effects of that financial downturn would soon pale in comparison, however, to the ravages of the coming war.

As the British Army under General Augustine Prevost descended on the peninsula of Charleston in early May 1779, the American forces defending the town panicked. The fortifications along the northern boundary of the town were incomplete, and the new houses in the village of Hampstead stood between Charleston and the approaching enemy, blocking the view of the American defenders. On May 9th, 1779, South Carolina Governor John Rutledge issued an order to raze Hampstead. Property owners were given a few hours to evacuate their possessions, and then the elegant new residences were put to the torch and pulled down. Two days later, General Prevost and his army quietly retreated from the peninsula without firing a shot at the town.[4]

As the British Army under General Augustine Prevost descended on the peninsula of Charleston in early May 1779, the American forces defending the town panicked. The fortifications along the northern boundary of the town were incomplete, and the new houses in the village of Hampstead stood between Charleston and the approaching enemy, blocking the view of the American defenders. On May 9th, 1779, South Carolina Governor John Rutledge issued an order to raze Hampstead. Property owners were given a few hours to evacuate their possessions, and then the elegant new residences were put to the torch and pulled down. Two days later, General Prevost and his army quietly retreated from the peninsula without firing a shot at the town.[4]

The British Army returned again in the spring of 1780, at which time General Henry Clinton laid siege to the town and battered Charleston into surrender. The smoking remnants of Hampstead suffered further insults during the siege, and the village was partially fortified. The American defenders built a small battery on the highest point in the village, a place near the intersection of Drake and Blake Streets called Hampstead Hill, which the British army captured and transformed into an even larger fortification.[5]

In the years after the conclusion of the Revolutionary War in 1783, more than two dozen Hampstead property owners petitioned the South Carolina General Assembly for compensation for the homes they lost in 1779 and 1780. Other village investors who remained loyal to the British crown had their property confiscated, and the process of settling these various claims dragged on for nearly twenty years.[6] The war had demolished the initial vision of Hampstead, but the village was reborn in the late eighteenth century as a new and more modest sort of suburban refuge.

The City of Charleston was formally incorporated in 1783, creating a more robust system of government and law enforcement for the more populous neighborhoods located south of Boundary Street (created in 1769, now Calhoun Street). Following that act, the unincorporated area north of Boundary Street, generally called “the Neck,” soon acquired a reputation as a place of relative freedom beyond the reach of city government. Taxes were lower, fewer laws were enforced, and there was less government oversight in general. To attract new residents and investors, many Hampstead property owners began subdividing their half-acre lots and erecting smaller buildings for shops and rental tenements. The extension of Meeting Street northward from Boundary Street, accomplished in 1785–86, cut a wide swath through the neighborhood, but it also provided a broad new path for commerce and people to flow between the countryside and the growing city.

Around the turn of the nineteenth century, Hampstead was home to a relatively diverse population, including affluent merchants and planters, middle-class tradesmen, free people of color, and enslaved day laborers. The absence of robust government oversight also attracted a variety of small shops, as well as larger commercial operations like ropewalks, slaughter pens, candle factories, and even a botanical garden. As political tensions between the United States and Britain increased to the brink of war in the early 1800s, however, the economy soured and growth stopped. When war was declared in the summer of 1812, the village of Hampstead was once again threatened with extinction.

After British forces captured and burned the American capital of Washington, D.C., in August 1814, and then laid siege to the port city of Baltimore in September, the people of Charleston feared that their homes would form the next British target. Throughout the autumn of 1814 and early 1815, the entire community worked in great haste to erect a new line of defensive fortifications across the peninsula from the Ashley to the Cooper River to protect Charleston’s northern boundary. These new defensive works included a zig-zag line of earthen walls fronted by a broad ditch or moat and were located about a half-mile north of similar fortifications erected during the American Revolution. As in that earlier war, when the fabric of Hampstead was sacrificed for the protection of urban Charleston, the line of fortifications erected in 1814–15 extended through the village and displaced a number of families. The wall and moat cut through the neighborhood, barracks were built on the northeast quadrant of Hampstead Mall, and a pentagonal structure called Fort Washington was erected on Hampstead Hill to surveil the Cooper River waterfront.

After British forces captured and burned the American capital of Washington, D.C., in August 1814, and then laid siege to the port city of Baltimore in September, the people of Charleston feared that their homes would form the next British target. Throughout the autumn of 1814 and early 1815, the entire community worked in great haste to erect a new line of defensive fortifications across the peninsula from the Ashley to the Cooper River to protect Charleston’s northern boundary. These new defensive works included a zig-zag line of earthen walls fronted by a broad ditch or moat and were located about a half-mile north of similar fortifications erected during the American Revolution. As in that earlier war, when the fabric of Hampstead was sacrificed for the protection of urban Charleston, the line of fortifications erected in 1814–15 extended through the village and displaced a number of families. The wall and moat cut through the neighborhood, barracks were built on the northeast quadrant of Hampstead Mall, and a pentagonal structure called Fort Washington was erected on Hampstead Hill to surveil the Cooper River waterfront.

The War of 1812, as we now call it, formally ended in the spring of 1815, at which time work on the newly-minted line of fortifications immediately ceased. These expensive but now obsolete works stood on private property confiscated by the government during a time of crisis, and the process of settling titles and claims to numerous parcels of land dragged on for nearly a decade after the war’s end. In the autumn of 1823, the property under the zig-zag line of fortifications stretching from the Ashley to the Cooper River was subdivided into dozens of lots sandwiched between two newly-created streets, named Line Street and Shepherd (now spelled "Sheppard") Street, and sold at auction. The physical remnants of those obsolete fortifications mostly disappeared in the late 1820s, but the effects of this second military incursion into Hampstead proved more lasting.

Beginning in the late 1820s and early 1830s, the village of Hampstead experienced a sort of third beginning. The most affluent property owners, who now resided outside the village, continued to subdivide their lots and to build an increasing number of rental tenements. Business such as foundries and machine shops, utilizing steam-powered equipment, moved into the neighborhood. Skilled and unskilled laborers, both black and white, enslaved and free, soon formed the majority of village’s population. Large numbers of European immigrants, mostly Irish and German, poured into the neighborhood in the 1840s and 1850s. Hampstead, and the adjoining neighborhoods comprising the unincorporated “Neck,” had matured into a diverse, populous, and increasingly unruly suburb.

After several years of complaining about its boisterous neighbor to the north, the City of Charleston gained permission from the state legislature in late 1849 to annex a large swath of “the Neck.” Hampstead Village and several other neighborhoods were incorporated into the city in 1850, at which time Charleston’s new northern boundary became Mount Pleasant Street. The act of annexation brought few changes to the formerly-independent village, at least at first. The streets remained unpaved, sandy thoroughfares, and municipal utilities like running water, sewerage, and street lights, would not arrive for many more decades.[7]

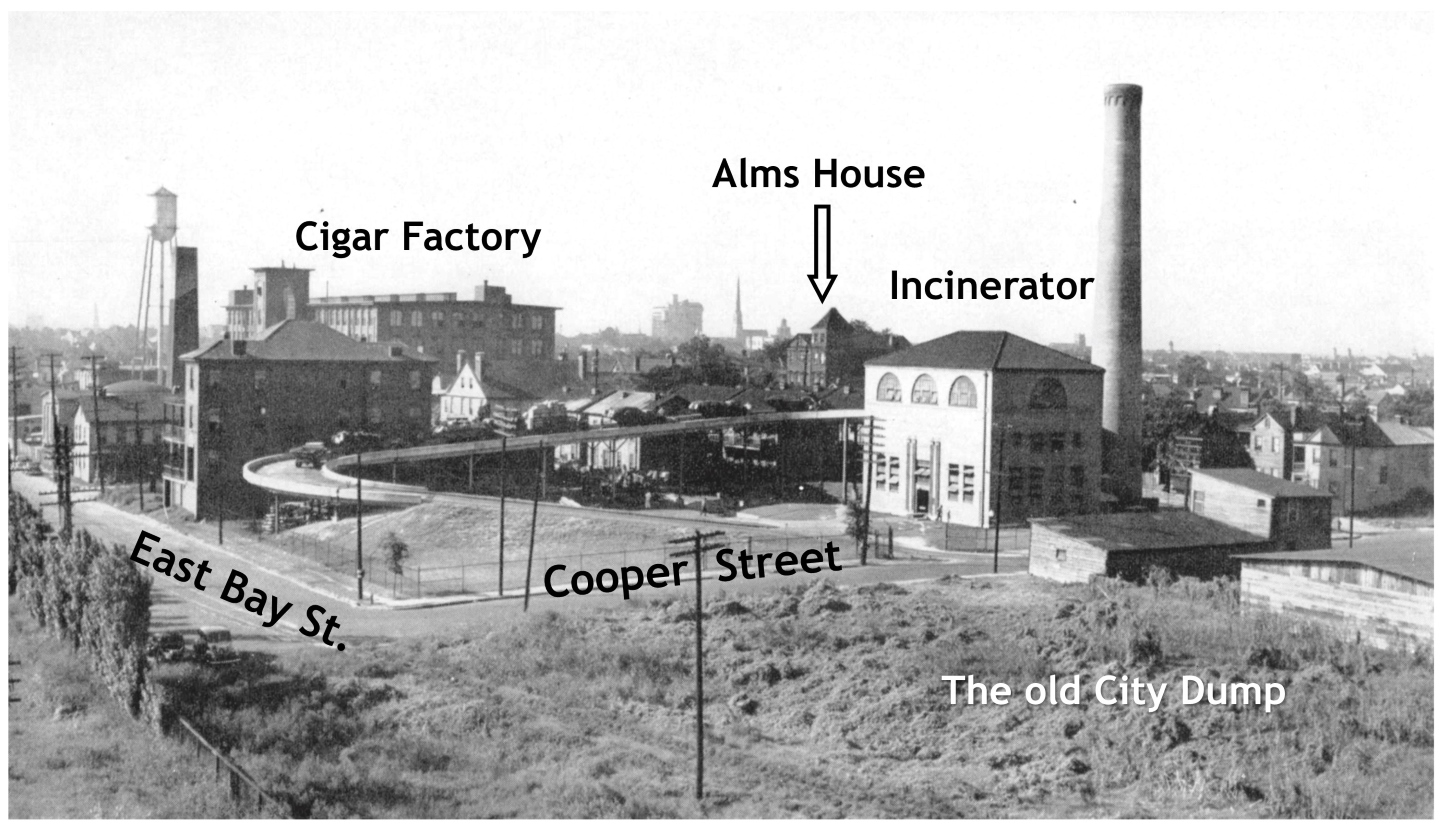

The construction of a large steam-powered cotton factory at the southwest corner of Columbus and Drake Street brought hundreds of jobs to the village in 1848, but the plant closed just three years later. The City of Charleston purchased the factory in 1852 to house hundreds of white children between August 1853 and October 1855, while the city’s Orphan House on Calhoun Street was renovated and expanded. After the children’s departure, the city closed its colonial-era Poor House on Mazyck Street (now Logan Street) and reopened the Columbus Street factory as the new Charleston Alms House in February 1856. For the next ninety-three years, that large building served as the epicenter of Charleston’s social welfare system.[8]

The construction of a large steam-powered cotton factory at the southwest corner of Columbus and Drake Street brought hundreds of jobs to the village in 1848, but the plant closed just three years later. The City of Charleston purchased the factory in 1852 to house hundreds of white children between August 1853 and October 1855, while the city’s Orphan House on Calhoun Street was renovated and expanded. After the children’s departure, the city closed its colonial-era Poor House on Mazyck Street (now Logan Street) and reopened the Columbus Street factory as the new Charleston Alms House in February 1856. For the next ninety-three years, that large building served as the epicenter of Charleston’s social welfare system.[8]

The Civil War decimated Charleston’s economy and brought significant damage to the city’s infrastructure. The decline of plantation agriculture forced the community to adapt to a more diversified economy, but skilled and unskilled labor continued to play an important role in the city’s commerce. Hampstead village, already a modest, working-class, mixed-race neighborhood, became increasingly diverse in the post-war years as large numbers of formerly-enslaved people moved from the rural plantations to seek a new a new life in Charleston. To capitalize on the neighborhood’s dense population, investors in the Charleston Manufacturing Company constructed a massive new cotton mill facing East Bay Street in 1882. Built on the southern part of Hampstead Hill, that cotton factory became a cigar factory in 1912, and still stands a major landmark on the eastern edge of Hampstead Village.[9]

At the end of the nineteenth-century, the culturally- and ethnically-diverse, working-class residents of Hampstead Village began to use their collective voice to lobby for improvements that other neighborhoods already enjoyed. Most of the residents worked outside the neighborhood, for example, but lacked the means to commute as easily as most other Charlestonians. In the spring of 1897, the local street car company finally agreed to include Hampstead within its grid of trolley service. The company laid a pair of steel rails down the center of Columbus Street—the village’s main street—and through Hampstead Mall to connect Hampstead to existing lines along Meeting and East Bay Streets.[10]

As pedestrian, horse, and trolley traffic increased along Columbus Street in the early twentieth century, the main street of Hampstead became an increasingly important commercial artery. The arrival of gasoline-powered automobiles in 1901 further augmented this traffic, and the city eventually consented to a major disruption of historic Hampstead Mall. The trolley line of 1897 had cut a narrow, east-west path through the park, but in 1905 the city formally divided the original square in two separate halves. Several large trees were removed and a fifty-foot wide path was cut through the mall to make Columbus Street “one uniform roadway” through the neighborhood. At the same time, the city paved the entire thoroughfare with red vitrified bricks, making Columbus the first paved street in the village.[11]

The trolley and automobile traffic through Columbus Street increased further after the opening of Union Station, a passenger railway terminal at the northeast corner of Columbus and East Bay Streets, in November 1907. Jobs and industry were rapidly moving out of the neighborhood, however, and Hampstead was too poor to keep pace with the changing world. In recognition that the majority of the residents in the neighborhood were poor and in need, the Catholic Diocese of Charleston opened a charity “Neighborhood House” at 77 America Street in 1915. By the 1920s, the general character of Hampstead’s dense, diverse, and poor population gave rise to a new nickname: “Little Mexico.”

The era of prohibition in the 1920s and 30s gave rise to numerous opportunities for quick profits from illegal alcohol. Little Mexico, connecting the waterfront with the city’s main arterial streets, soon earned a reputation with the Charleston police as a nest of gin factories, flop houses, gambling dens, and criminal activity in general. One resident complained in 1925 that there was “shooting around there all the time.”[12] The opening of the first Cooper River Bridge in 1929, located on the northern edge Hampstead Village, further contributed to neighborhood’s transient and declining reputation. On the other hand, the bridge project also forced the city to clean up the sprawling and rat-infested open-air trash dump that the city had imposed on the neighborhood decades earlier. To accommodate this change, the City of Charleston built a municipal trash incinerator on the northern end of Hampstead Hill. Opened in 1935 and later expanded, the old incinerator’s tall brick smokestacks still form a very visible landmark today, next to the incinerator building now called the St. Julian Devine Community Center.

Charleston was one of many urban centers in the United States to witness a declining population in the years immediately after the end of World War 2. The so-called “white flight” to the new suburbs west of the Ashley River sapped much of Hampstead’s vitality and diversity in the late 1940s and early 1950s. For the first time in its peacetime history, the neighborhood’s population began to decline. This negative trend was compounded by a series of other events. The passenger train terminal at the east end of Columbus Street, Union Station, burned in November 1947 and closed permanently. The Charleston Alms House, renamed the Charleston Home in 1913, closed its doors at the end of 1949 and left an abandoned brick shell. In the spring of 1956, city workers removed more large oak trees from Hampstead Mall to extend America Street through the old village square, creating the four smaller parks that we see today.[13]

Charleston was one of many urban centers in the United States to witness a declining population in the years immediately after the end of World War 2. The so-called “white flight” to the new suburbs west of the Ashley River sapped much of Hampstead’s vitality and diversity in the late 1940s and early 1950s. For the first time in its peacetime history, the neighborhood’s population began to decline. This negative trend was compounded by a series of other events. The passenger train terminal at the east end of Columbus Street, Union Station, burned in November 1947 and closed permanently. The Charleston Alms House, renamed the Charleston Home in 1913, closed its doors at the end of 1949 and left an abandoned brick shell. In the spring of 1956, city workers removed more large oak trees from Hampstead Mall to extend America Street through the old village square, creating the four smaller parks that we see today.[13]

The biggest change in the post-war era was the demographic profile of Hampstead’s residents. Between the Federal Censuses of 1950 and 1960, the neighborhood’s population shifted from being predominantly white to predominantly African-American. That demographic transition did not happen overnight, of course. Rather, the exodus of white residents and the influx of black residents from other neighborhoods south of Calhoun Street was a general trend throughout the decade. In 1954, for example, the Charleston School Board purchased and demolished the old Alms House building, and in 1957 opened the Columbus Street Elementary School for black children. (The school was renamed for educator Wilmot Jefferson Fraser in 1979). By the spring of 1959, the majority of registered voters in Charleston’s Ward No. 9, which included Hampstead, were non-white. That unprecedented change worried many conservative white politicians, whose prejudiced opinions served to further isolate and stigmatize the neighborhood.[14] In the wake of census polling in 1960, the City of Charleston re-designated the white-only playground at Hampstead Mall to be a “colored playground.”[15] In order to provide equitable educational facilities for black teenagers, the Charleston School Board seized property adjoining the northeast quadrant of Hampstead Mall for the construction of Charles A. Brown High School, which opened in 1962.

In the early 1960s, many people in the Charleston area began to view the Hampstead neighborhood as a distinct, isolated, and undesirable enclave within a larger, more homogenous community. In other words, Hampstead came to be viewed as a ghetto, and that discriminatory mentality quickly eroded its two centuries of identity as a mixed-race, working-class village. As the neighborhood’s overall population shrank, many of its modest but historic homes became vacant, boarded-up eyesores that lured transients and illegal activity. Many homes still lacked modern water and sewer facilities, and there was little economic incentive to modernize declining properties.[16] Politicians, neighbors, and the police began to complain about the increase in crime and delinquency in Ward No. 9, located on the east side of the Charleston peninsula.[17] The name “Hampstead” gradually disappeared from the Charleston lexicon in the early 1960s, as the chorus of complaints about the “East Side” grew louder. By 1965, the city was using Federal grant money to help reduce juvenile crime in Charleston’s “East Side,” and by 1966 there was a grassroots “Eastside Development Council” campaigning to improve the neighborhood’s economic health.[18] Stay away from the East Side, parents told their children. Help us improve the East Side, residents begged the city.

The sisters of Our Lady of Mercy who ran the Catholic charity called the “Neighborhood House” at 77 America Street during the course of the twentieth century had a front-row seat to Hampstead’s gradual evolution. From its beginning in 1915 to 1932, the majority of the people who sought assistance at the Neighborhood House were white and Catholic. Between 1933 and 1952, the institution’s customers were mainly white and Protestant. From 1953 the 1963, however, the charity’s clientele became predominantly black Protestants. A statement published in 1967 reported that 99% of those seeking aid at the Neighborhood House were poor black residents.[19] A news article published in the summer of 1969 described Charleston’s East Side neighborhood as “the most densely populated area per square block in the State of South Carolina,” and among the poorest as well.[20]

As the Charleston-metro area expanded and modernized in the late twentieth century, the city’s East Side continued to struggle for survival. New residents, increasing numbers of tourists, and valuable commercial investment—especially after Hurricane Hugo in 1989—transformed Charleston into an increasingly desirable destination, but the economic benefits of this trend largely bypassed the East Side. By the turn of the twenty-first century, the heart of the East Side—the neighborhood formerly known as Hampstead Village—looked much as it had forty years earlier. In more recent years, however, the strength of Charleston’s real estate market has focused an unprecedented degree of attention on the rapidly-diminishing quantity of “affordable” property on the peninsula. The East Side, once viewed as a dangerous ghetto, is increasingly seen as the new frontier for wise investment. The number of white residents and college students in the neighborhood is steadily increasing. This change might seem like a radical shift to some today, but I’d like to propose a different, more historical view of the present situation.

As the Charleston-metro area expanded and modernized in the late twentieth century, the city’s East Side continued to struggle for survival. New residents, increasing numbers of tourists, and valuable commercial investment—especially after Hurricane Hugo in 1989—transformed Charleston into an increasingly desirable destination, but the economic benefits of this trend largely bypassed the East Side. By the turn of the twenty-first century, the heart of the East Side—the neighborhood formerly known as Hampstead Village—looked much as it had forty years earlier. In more recent years, however, the strength of Charleston’s real estate market has focused an unprecedented degree of attention on the rapidly-diminishing quantity of “affordable” property on the peninsula. The East Side, once viewed as a dangerous ghetto, is increasingly seen as the new frontier for wise investment. The number of white residents and college students in the neighborhood is steadily increasing. This change might seem like a radical shift to some today, but I’d like to propose a different, more historical view of the present situation.

I’ve heard some long-time residents assert that the East Side has always been a predominantly black neighborhood, and that recent demographic changes represent the forces of gentrification and the harbinger of eventual displacement. Taking a broader view of the issue, however, I would argue that the neighborhood is slowly returning to the sort of demographic equilibrium that it enjoyed in earlier generations. In my opinion, informed by my experience as a Charleston historian, the name “East Side” itself is problematic. That generic name first appeared in the local press during the early 1960s, at a time when predominantly-white local authorities first began to recognize that the city’s Ward No. 9 had achieved a black majority. In their minds, that simple fact was disconcerting. In the early 1960s, it was easier for them to say “the East Side is a problem area,” than to admit “we have a problem with social, economic, and racial disparity in historic Hampstead.”

There have been many heroes campaigning for the improvement of the East Side neighborhood over the past sixty years, and local government has not been completely blind to the issues at hand. I’ve omitted a number of story lines and details from this brief historical overview, of course, but my goal was to provide the community with a broad perspective that might help facilitate conversations about the neighborhood’s future. As we mark the 250th anniversary of the founding of Hampstead Village, perhaps we can reflect on the multiplicity of stories and identities contained within its historic bounds and derive inspiration for the next two-and-a-half centuries.

Identity, both personal and communal, is an important and necessary part of empowerment. Perhaps by reclaiming this neighborhood’s largely-forgotten historic name, Hampstead, and its diverse heritage, we can muster the strength to move forward together and overcome the legacy of discrimination and disparity that gave rise to the name “East Side” nearly sixty years ago.

[1] Henry A. M. Smith, “Charleston and Charleston Neck: The Original Grantees and the Settlements along the Ashley and Cooper Rivers,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 19 (January 1918): 10–12; George C. Rogers, et al., eds., The Papers of Henry Laurens, volume 7 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1979), 589–95. A plan of "The Village of Hampstead," made by William Davis on 6 December 1769, survives as a copy made on 28 May 1820 by Daniel H. Tillinghast, Surveyor General; see South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Copies of Plats and Plans (S213187), volume 1, page 12.

[2] The initial sale advertisement appeared in South Carolina and American General Gazette, 20–27 November 1769; South Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, 28 November 1769, page 3; South Carolina Gazette, 30 November 1769, page 2.

[3] See the general Hampstead advertisement in South Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, 13 March 1770, page 4; John Bull’s advertisement for Lots 72 and 73 in South Carolina Gazette, 31 December 1772.

[4] The burning of Hampstead is described in dozens of petitions submitted to the South Carolina General Assembly in the years after the war, which are now held by the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia See, for example, Petitions to the General Assembly, 1784, No. 51; 1785, No. 98; 1796, No. 62.

[5] The fortifications at “Hampstead Hill” appear on several maps of the 1780 siege made by British, French, and American engineers.

[6] The surviving records of the post-Revolutionary-war claims for lost and confiscated property are found among the petitions to the South Carolina General Assembly, at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History, and the subsequent committee reports on the various petitions.

[7] For a more detailed study of the neighborhood’s early history, see Dale Rosengarten, et al., “Between the Tracks: Charleston’s East Side During the Nineteenth Century,” Archaeological Contributions 17 (Charleston, S.C.: The Charleston Museum, 1987).

[8] Benjamin Joseph Klebaner, “Public Poor Relief in Charleston, 1800–1860,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 55 (1954): 210–20.

[9] For a brief history of the Cigar Factory see its National Register description on the website of the South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

[10] At a meeting held on 23 March 1897, City Council approved a plan submitted by the Charleston City Railway Company to construct an electric trolley rail line in the center of Columbus Street, "through the Mall"; see the official proceedings of City Council in Charleston News and Courier, 25 March 1897, page 3. This route became operational on 11 July 1897; see Charleston News and Courier, 11 July 1897, page 8, "The East Bay Route."

[11] See the proceedings of the City Council meeting of 25 April 1905 in Charleston Evening Post, 27 April 1905, page 6; Charleston News and Courier, 18 May 1905, page 1, “Trees on Mall Felled.”

[12] Charleston Evening Post, 24 February 1925, page 12, “Golnick Held By Coroner.” For other examples of complaints about “Little Mexico,” see Evening Post, 4 July 1928, page 10, “Police Seize 2 Automobiles”; News and Courier, 22 August 1928, page 9, “Little Mexico Goes To Court”; News and Courier, 2 May 1929, page 2, “Constables Seek Gambling In Vain”; News and Courier, 31 May 1934, page 13, “Seizure Of Liquor Draws Crowd’s Ire.”

[13] City workers began removing trees for the extension of America Street through Hampstead Mall on 1 March 1956; see photo in Charleston News and Courier, 2 March 1956, page 6-B. The route opened for vehicular traffic on 1 May 1956; see Charleston Evening Post, 1 May 1956, page 1-B, “Traffic Moves on New Section of America St.”

[14] Charleston News and Courier, 3 March 1959, page 8, “Negro Democrats Now in Control of Charleston’s Ward Nine Voting.”

[15] Charleston Evening Post, 5 August 1960, “White Playground Given to Negroes.”

[16] Charleston Evening Post, 17 April 1973, page 11A, “Many Causes Exist for Area’s Decline.”

[17] For one of numerous examples of this trend, see Charleston Evening Post, 27 November 1963, pages 1 and 2, “More Police Protection is Urged.”

[18] See Charleston Evening Post, 1 September 1965, page 11, “Youth Development Project Begins In Area of City”; Charleston News and Courier, 13 May 1966, page 10, “STEP Group Will Continue East Side Cleanup Project.”

[19] Charleston News and Courier, 17 July 1967, page 13, “Environment Rules Work of Settlement Houses.”

[20] Charleston News and Courier, 17 July 1969, page 7B, “East Side Community Center Fund-Raising Campaign Set.”

PREVIOUS: From Intendant to Mayor: The Evolution of Charleston’s Executive Office

NEXT: Mackey’s Morphine Madness: The 1869 Shootout at Charleston's City Hall, Part 1

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments