John Laurens and Hamilton: A Closer Look, Part 2

Processing Request

Processing Request

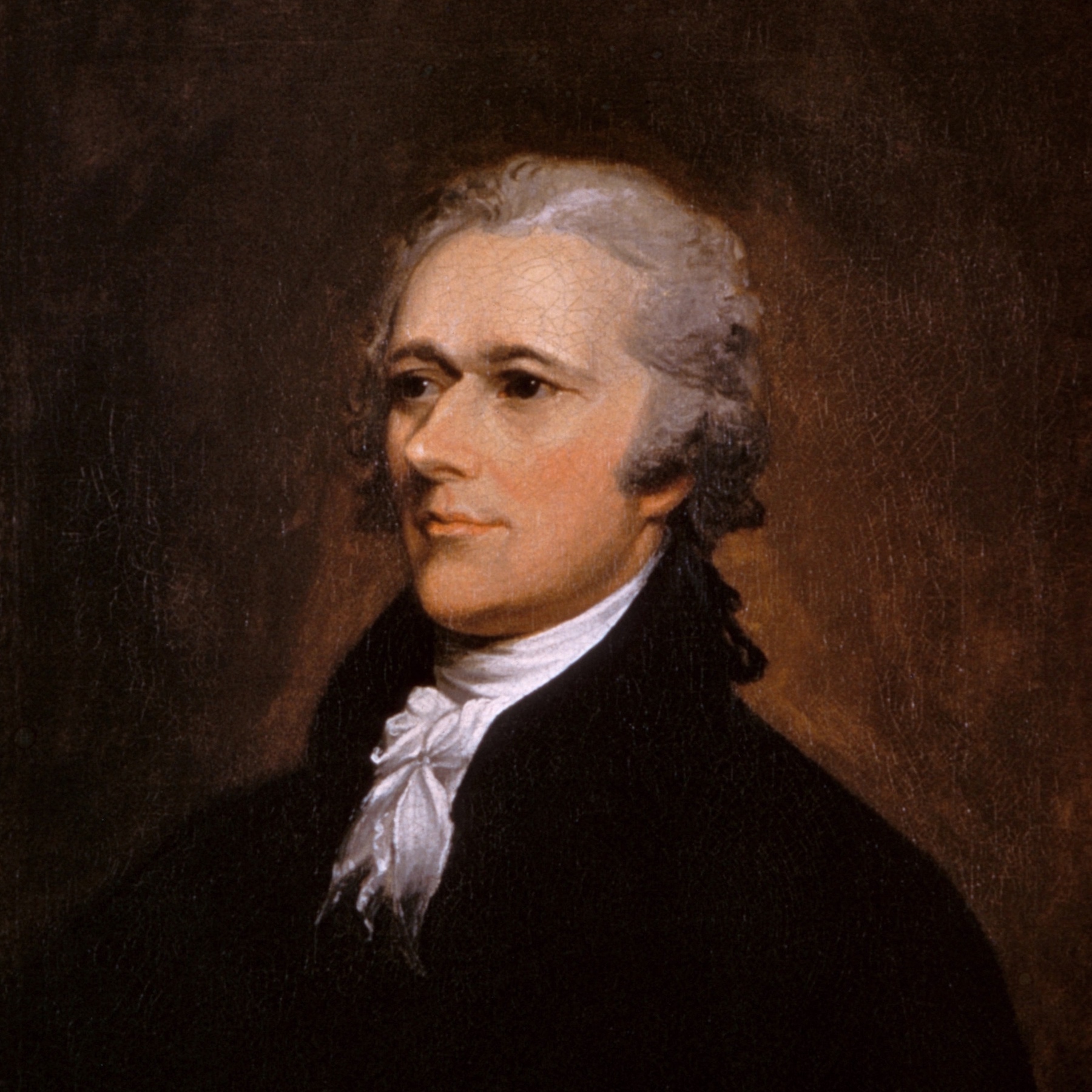

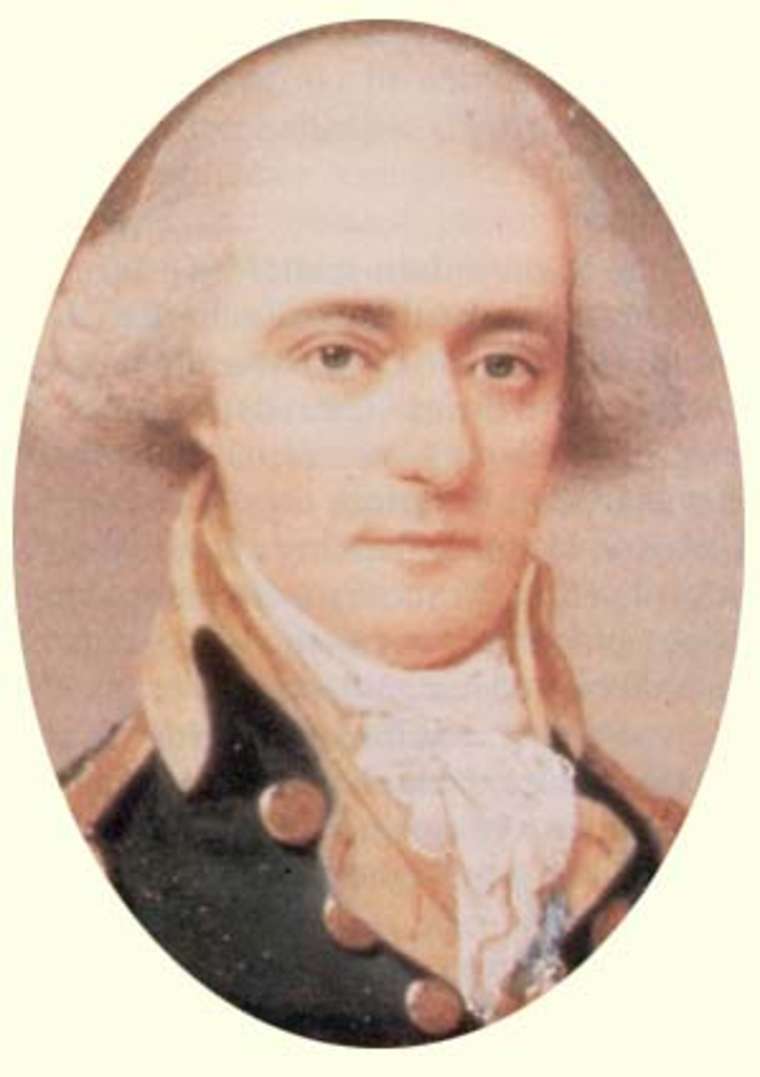

Today we’re going to continue with the story of John Laurens, a Charleston native who’s one of the principal characters in Act One of the hit Broadway musical, Hamilton. In our last episode, we began with Ron Chernow’s award-winning biography of Alexander Hamilton, which served as the inspiration for Lin-Manuel Miranda’s blockbuster musical that is currently sweeping the nation with tickets costing thousands of dollars. But our main interest is examining the real story of the life of John Laurens, Hamilton’s best friend and confidante during the American Revolution. The portrayal of Laurens in both Chernow’s book and Miranda’s musical is not entirely accurate, so we delved into the details of John’s early life and his entry into the war that defined his career. When we left off, twenty-three-year-old Major John Laurens had asked his father, Henry, for permission to use family-owned slaves as the core of a new regiment of soldiers to help defend South Carolina from British attack. The elder Laurens rebuffed John’s plan, however, and questioned the sincerity of his son’s efforts to use the army as a path to the emancipation of all slaves. In the spring of 1778, the young John Laurens dropped the matter and moved on to the more immediate needs of the American army as it clashed with British forces around the Delaware River.

In late June, John Laurens rode furiously into the Battle of Monmouth, New Jersey, but a bullet brought down his horse. In July and August of 1778, John Laurens was in Newport, Rhode Island, acting as a mediator between quarreling American and French officers who were trying to dislodge the British forces holding that important port town. Although their efforts were unsuccessful, the 1778 Siege of Newport was remarkable for two reasons. First, it was the first joint operation between the Americans and their new allies, the French army and navy, who had just partnered with us in the war against Britain. Second, the American forces involved in the 1778 siege included the First Rhode Island Regiment, which consisted of black, white, and Native-American soldiers, all wearing the uniform of the United States Continental Army. The First Rhode Island is sometimes called the “black regiment” because it included men of African descent, but it was actually a mixed-race regiment. At any rate, for the present storyline, it’s important to note that John Laurens was on the ground at the Siege of Newport when black soldiers fought along their lighter-skinned comrades.[1]

Although the joint American and French siege did not succeed in dislodging the British from Newport, the affair gave John Laurens the opportunity to practice his fluent French in an effort to smooth over diplomatic relations between the new allies. A few weeks later, in September 1778, the Continental Congress offered to appoint John secretary to the American delegation at the Court of France. Ever in search of glory on the battlefield, John Laurens refused the appointment, and rejoined General Washington’s staff in Philadelphia.

A month later, in early November 1778, Congress resolved to offer a promotion to John Laurens. The delegates thanked the young officer for his patriotic zeal, especially at the recent battle of Rhode Island, and offered him a commission as lieutenant colonel in the Continental Army, but John refused. The twenty-four-year-old Laurens was certainly ambitious, but he worried that such a promotion would create an impression of nepotism. After all, his father, Henry Laurens, just happened to be president of Continental Congress at that time.[2]

A month later, in early November 1778, Congress resolved to offer a promotion to John Laurens. The delegates thanked the young officer for his patriotic zeal, especially at the recent battle of Rhode Island, and offered him a commission as lieutenant colonel in the Continental Army, but John refused. The twenty-four-year-old Laurens was certainly ambitious, but he worried that such a promotion would create an impression of nepotism. After all, his father, Henry Laurens, just happened to be president of Continental Congress at that time.[2]

Major John Laurens was a proud member of General Washington’s staff, and he was among several junior officers who were offended by General Charles Lee, who was spreading harsh criticism about the commander-in-chief behind Washington’s back in late 1778. General Lee’s poor command at the Battle of Monmouth, a few months earlier, led to a court-martial that found him guilty of misbehavior and insubordination. Washington relieved Lee of his command, and Lee began bad-mouthing Washington. In the rarified atmosphere of military politics and pretentions of aristocratic honor, John Laurens could not tolerate such un-gentlemanly behavior. He challenged Lee to a duel, and they fought with pistols on December 23rd. Laurens escaped the encounter unharmed, but Lee received a wound in his side, from which he later made a full recovery.[3]

The 1778 Laurens-Lee duel is rendered, with reasonable accuracy, in Act 1 of the musical, Hamilton, in a number called “Ten Duel Commandments.” Rather than engaging the actual story, however, that number simply recites the purported rules of dueling. If this were a musical about John Laurens, perhaps this scene would offer insight into the heightened sense of honor that compelled Laurens to challenge Lee to a potentially fatal fight. But this is a musical about Alexander Hamilton, who acted as John’s second in the 1778 duel, and so the scene simply serves to foreshadow the manner of Hamilton’s untimely death at the end of Act 2.

In December 1778, Hamilton, Laurens, and Lee had free time to get caught up in matters of honor because the war had ground to a halt in the north. After two and a half years of fighting, primarily in the northeastern states, the Americans and British armies were at a stalemate. Meanwhile, the British command embarked on a new strategy to move the war southward, where they felt they might find more support from loyalists. In late December 1778, just a week after the Laurens-Lee duel, the British army captured the port of Savannah Georgia, after meeting with minimal resistance. When Continental Congress reconvened in January 1779, the prospects for the success of the Revolution seemed to be evaporating. American resistance in Georgia was rapidly crumbling, and it was obvious that the British meant to use Savannah as a springboard for attacking South Carolina. Major John Laurens asked General Washington for a leave of absence to return to Charleston, hoping that he could assist in the American defense of his home turf. Alexander Hamilton also applied for leave, hoping to accompany his best friend southward and to follow the heat of battle. Washington released Laurens with good wishes, but he kept Hamilton at general headquarters in Philadelphia.[4]

In March of 1779, the Continental Congress accumulated reports about both the strength of the American army and the extent of the dangers facing South Carolina. Congress admitted that it had no resources to offer, and reports coming from Charleston confirmed that South Carolina certainly did not have sufficient resources to fend off a large-scale British assault. The people of South Carolina felt that they had been neglected and abandoned by Congress, and morale was deteriorating rapidly. In response, Congress appointed a committee, including South Carolina’s representatives, William Henry Drayton and Henry Laurens, to draft some recommendations for our defense. After weighing the evidence and debating the course of action, Drayton, Laurens, and the rest of the committee were forced to admit that the notion of arming enslaved black men sounded like their only hope of repulsing a British assault on South Carolina. In private letters between father and son, Henry Laurens reluctantly endorsed John’s desire to form a black regiment, and he pledged to help get Congressional support for the plan. General Washington was ambivalent, however, worrying that such a move would spark a rapidly escalating and chaotic arms race, in which the British would scurry to arm even more slaves than the Americans. Undaunted by the apathy of the commander-in-chief, Henry Laurens and his committee reported on March 25th, urging Congress to take the unprecedented step of approving the enlistment of black soldiers to help defend South Carolina.

After some debate, on March 29th, Congress reluctantly approved a plan to raise a regiment of 3,000 black soldiers in South Carolina. This was not an order or a fait accompli, however, but merely an emergency recommendation to be offered to and considered by the legislature of South Carolina. On that same day, Continental Congress also granted a commission promoting Major John Laurens to the rank of lieutenant-colonel, but we have to exercise caution in linking these two events. If you look at the official text of the congressional journal for March 29th, 1779, which you can read in its entirety online, Congress did not specify that John Laurens was to command the proposed regiment of black soldiers, nor did it specify that John Laurens was to carry the proposal to South Carolina, or even to lobby for its approval there. By approving the plan for a black regiment to be recommended, and then promoting John Laurens to a regimental-commanding rank, a connection between these matters is certainly implied, but it is not articulated. Nevertheless, we can all agree on the fact that when Lt. Col. John Laurens packed his bags and set out for South Carolina in April of 1779, his head was full of ideas about how to make his dream of leading a black regiment on his home turf a reality.[5]

After some debate, on March 29th, Congress reluctantly approved a plan to raise a regiment of 3,000 black soldiers in South Carolina. This was not an order or a fait accompli, however, but merely an emergency recommendation to be offered to and considered by the legislature of South Carolina. On that same day, Continental Congress also granted a commission promoting Major John Laurens to the rank of lieutenant-colonel, but we have to exercise caution in linking these two events. If you look at the official text of the congressional journal for March 29th, 1779, which you can read in its entirety online, Congress did not specify that John Laurens was to command the proposed regiment of black soldiers, nor did it specify that John Laurens was to carry the proposal to South Carolina, or even to lobby for its approval there. By approving the plan for a black regiment to be recommended, and then promoting John Laurens to a regimental-commanding rank, a connection between these matters is certainly implied, but it is not articulated. Nevertheless, we can all agree on the fact that when Lt. Col. John Laurens packed his bags and set out for South Carolina in April of 1779, his head was full of ideas about how to make his dream of leading a black regiment on his home turf a reality.[5]

Almost immediately after returning to South Carolina, John Laurens’s zeal for military glory got him into hot water. While shadowing the movements of British forces along the state’s southern frontier in early May 1779, Laurens acted in violation of direct orders by engaging a large enemy force at Coosawhatchie Bridge with a relatively small force of Continental soldiers and militia. Laurens was wounded and lost his horse in the brief skirmish, but more importantly his reputation was sullied by the poor judgment he showed. By needlessly exposing men to danger for his own personal glory, Laurens’s poor leadership demoralized the troops and inspired the desertion of many militiamen. The timing couldn’t have been worse. British forces under General Augustine Prevost pushed northward from Savannah and stopped right at the gates of Charleston, where they demanded the town’s surrender in mid-May 1779. After contemplating surrender, the American command resolved to dig in their heels and fight. In the meantime, Prevost and his troops retreated back towards Georgia, and all of Charleston breathed a sigh of relief.[6]

Shortly after this close call, John Laurens wrote to the Governor of South Carolina, his family friend, John Rutledge, asking him to consider the Congressional proposal for arming 3,000 slaves. Governor Rutledge presented the idea to his cabinet of advisors, called the Privy Council, and shortly afterward informed Laurens that they had rejected the idea. But John Laurens wasn’t about to give up the fight. In July 1779 Laurens took his seat in the South Carolina House of Representatives (to which he had been elected in December 1778) and waited for the opportunity to argue for the creation of a black regiment. The text of John’s speech on this matter does not survive, nor does the text of the debate that followed, but we do know that the proposal was easily defeated. According to contemporary accounts, the motion to create a force of 3,000 armed slaves garnered a few votes of support, but the vast majority of the slave-holding legislators voted against the plan.[7]

In the late summer of 1779, French naval forces arrived in Charleston, and the American command began planning an attack on the British-held town of Savannah. Preparations continued throughout the month of September, and the battle was finally joined on October 9th. On that day, Lt. Colonel John Laurens commanded the South Carolina Continental light infantry and dragoons, and the joint Franco-American forces stormed the British lines at daybreak. It was a disaster. A litany of missteps doomed the assault before it even began, but the American and French soldiers fought bravely. British cannon and musket fire cut down scores of soldiers before the American command ordered a general retreat. The scene was chaotic, and John Laurens felt ashamed by the senseless loss of life on that day.[8]

Meanwhile, back in Philadelphia, the Continental Congress unanimously elected John Laurens to be secretary to Benjamin Franklin in Paris. Laurens refused the appointment, however, preferring to remain at home to help drive out the British army out of the south. To help further this cause, Laurens sailed to Philadelphia in late November 1779 and lobbied Congress to send much-needed reinforcements to South Carolina. Even General Washington admitted that the situation in the south was more desperate than he had first imagined. Frustrated by the inability of Congress to help, Laurens rode southward and was back in Charleston by mid-January 1780. By that time, it was clear that a massive British force was gathering offshore for an assault on Charleston, and the situation was nothing short of a major crisis. In the South Carolina House of Representatives, that February, John Laurens once again pleaded with his colleagues to equip slave with weapons to help defend the town, and once again his pleas were rejected.[9] Meanwhile, Sir Henry Clinton and approximately 8,000 British soldiers were closing in on Charleston, and the legislature adjourned to the battlefield.[10]

After a bloody two-month siege, the Americans surrendered Charleston on May 12th, 1780. John Laurens and nearly 6,000 American troops became prisoners of war, but not all of them were treated equally. The militiamen were sent home on parole. Some officers and civilians were packed aboard prison ships in the harbor. Many Continental officers were sequestered at barracks in what is now Mt. Pleasant. John Laurens and Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, as very important persons, were sent to Philadelphia in June 1780, where they waited to be formally exchanged and allowed to return to duty. After Laurens was exchanged in November 1780, Congress appointed him to undertake a special mission to France to help secure assurances that the French navy would assist the American army in upcoming campaigns. To assist him on this trip, Laurens chose a Charleston friend, Major William Jackson (1759–1828) to be his secretary, and they departed from Boston in early February 1781.[11]

Two months later, in April, John Laurens’s eloquent diplomacy helped to convince the French government to expedite its monetary and military aid to the United States. Many years later, his secretary, William Jackson, wrote a brief narrative of Laurens’s mission, which was published in 1828 by another Charleston friend, Major Alexander Garden. In short, Laurens boldly but politely informed the French that if they withheld immediate aid to the Americans, he and the rest of the Continental army would inevitably return the next year under British command, and the enemies of France will thus have doubled in size. Modern historians seem to minimize Laurens’s contribution to the French mission of 1781, so we have to trust William Jackson in his account of the scene.

Two months later, in April, John Laurens’s eloquent diplomacy helped to convince the French government to expedite its monetary and military aid to the United States. Many years later, his secretary, William Jackson, wrote a brief narrative of Laurens’s mission, which was published in 1828 by another Charleston friend, Major Alexander Garden. In short, Laurens boldly but politely informed the French that if they withheld immediate aid to the Americans, he and the rest of the Continental army would inevitably return the next year under British command, and the enemies of France will thus have doubled in size. Modern historians seem to minimize Laurens’s contribution to the French mission of 1781, so we have to trust William Jackson in his account of the scene.

At any rate, John Laurens felt that he had achieved his mission to France, so he turned over his duties to Major Jackson and set sail for America at the beginning of June 1781. Having spent less than three months in France, preoccupied with diplomatic matters, he was eager to return to the battlefield. In his haste, Laurens passed up the opportunity to see his wife, Martha, and daughter, Frances (remember them?). While waiting to see her husband in France, Martha Manning Laurens died in the autumn of 1781, leaving little Frances an orphan without a country.[12]

John Laurens arrived in Boston near the end of August, and by early September 1781 he was in Philadelphia unloading French supplies for Washington’s army. His timing couldn’t have been better. Washington and his army, including Alexander Hamilton and the Marquis de Lafayette, were just setting out for Virginia, where they hoped to coordinate with the French navy to trap a large British force under General Cornwallis. With fresh supplies and French reinforcements, spirits were high in the autumn of 1781 as the Continental forces and militia converged on Yorktown. In mid-October, Lt. Colonels John Laurens and Alexander Hamilton led the American assault on British Redout No. 10 at the Battle of Yorktown, which helped pave the way for the American victory. After another day of fighting, the British guns fell silent.

Was this the end of the war? Did the outcome of the battle seem as if the world had been turned upside down? Was this the moment for John Laurens to exact revenge for the British treatment of his countrymen at the surrender of Charleston? Tune in next time for the continuation of the dramatic adventures of John Laurens, here on the Charleston Time Machine.

[1] For details of the battle of Monmouth, see Gregory D. Massey, John Laurens and the American Revolution (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000), 108–10; for Newport, see 114–20.

[2] Massey, John Laurens, 123–24.

[3] Massey, John Laurens, 125–26.

[4] Massey, John Laurens, 130–31.

[5] Massey, John Laurens, 132; Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress 1774–1789, volume 13 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909), 374, 384–89.

[6] Massey, John Laurens, 135.

[7] Massey, John Laurens, 140–41.

[8] Massey, John Laurens, 144.

[9] Massey, John Laurens, 155.

[10] Massey, John Laurens, 148–49.

[11] Massey, John Laurens, 162–72.

[12] See Alexander Garden, Anecdotes of the American Revolution, Illustrative of the Talents and Virtues of the Heroes and Patriots, Who Acted the Most Conspicuous Parts Therein. Second Series (Charleston, S.C.: A. E. Miller, 1828), 12–19: “Embassy of Lieut. Col. Laurens to France.” Massey, John Laurens, 173–94, also discusses the French mission in detail.

NEXT: John Laurens and Hamilton, Part 3

PREVIOUSLY: John Laurens and Hamilton, Part 1

See more from Charleston Time Machine