The Moving Memorials to Elizabeth Jackson

Processing Request

Processing Request

Two granite memorials in urban Charleston recall the story of Elizabeth Jackson, an obscure Irish immigrant who passed the final years of her life in South Carolina. She died in or near the Palmetto City during the American Revolution, but the site of her burial has long been a mystery. Efforts to celebrate her memory have been confounded by misinterpretations of the clues surrounding her final resting place, with two monuments potentially misleading visitors. By carefully examining the historic evidence, we can point more confidently to a long forgotten site on the modern landscape.

Elizabeth Hutchinson Jackson (ca. 1740–1781) is best remembered today as the mother of Andrew Jackson (1767–1845), the military leader who won enduring fame after leading American forces to victory in the Battle of New Orleans in January 1815. Although General Jackson then went on to become a savage proponent of Indian expulsion and was responsible for the dislocation of tens of thousands of Native Americans from their traditional homelands in the Southeast, he achieved greater fame as the seventh president of the United States (1829–1837).

President Jackson lost both his parents and all his siblings before his fifteenth birthday, and that loss had a profound effect on the formation of his adult personality. Jackson was a physically small man with humble roots, but he gained legions of admirers in the early nineteenth century with his larger-than-life, indomitable and irascible personality. Over the past two centuries, numerous writers have published stories about Andrew Jackson’s childhood, but there are very few bona fide, reliable facts known about his family and his early years. Many of those publications contain highly Romanticized, unverifiable statements, and some are embellished with outright fabrications.[1]

Inspired by this mass of semi-fictional biographical literature, Charlestonian in the mid-twentieth century erected two different monuments to the memory of Jackson’s mother, who is said to have died in or near the city. To understand the motivations behind these memorials, and to appreciate the years of confusion related to their physical locations, we have to journey back in time to the beginning of the story and march towards the present.

Inspired by this mass of semi-fictional biographical literature, Charlestonian in the mid-twentieth century erected two different monuments to the memory of Jackson’s mother, who is said to have died in or near the city. To understand the motivations behind these memorials, and to appreciate the years of confusion related to their physical locations, we have to journey back in time to the beginning of the story and march towards the present.

The Jackson family came from County Antrim in the north of Ireland around the year 1765 and settled with relatives in the Waxhaw region that straddles the border between North and South Carolina. Although there has been much debate about whether the seventh president was born on the north or south side of that border, Jackson always identified himself as a native of South Carolina. Andrew’s father died shortly before his birth in 1767, and his mother, Elizabeth, struggled to raise three young boys in a frontier farming community that included members of her extended family.

The advent of the American Revolution in 1775 brought much strife to the Waxhaws, and most of the community favored independence from Britain. Hugh Jackson, eldest brother of the future president, died after the Battle of Stono Ferry, near Charleston, in June 1779. Teenaged Andrew and his older brother, Robert, served as couriers for the local militia after that time and witnessed much bloodshed. Both boys were captured by British forces in April 1781 and confined to a military prison in Camden. Mrs. Jackson secured the release of her two sons a month later, by which time the boys had contracted smallpox and were very weak. Robert died shortly after their return to the Waxhaws, but Andrew recovered.

A short time after the death of young Robert Jackson, most likely in early June 1781, Elizabeth Jackson decided to journey approximately 170 miles to Charleston. British forces had captured the capital of South Carolina on May 12th, 1780, and used the town as a base of operation throughout the state. Many biographers of the seventh president have asserted that Mrs. Jackson volunteered to nurse American soldiers imprisoned by enemy forces in Charleston, but her mission might have been more specific. A large-scale exchange of prisoners was to take place in June and July, and Elizabeth knew of two nephews held in Charleston who would need assistance in returning home.[2]

Fourteen-year-old Andrew was still weak from his confinement, so his mother placed him the household of some nearby relations. Before parting from her only surviving son, Elizabeth Jackson gave the boy some words of advice that he cherished for the rest of his life. Various biographers over the years have published different versions of this advice, ranging from an elegant homily to few terse commands. The latter seems more likely, considering the circumstances and the characters involved. One account, published by a man who heard President Jackson tell the story in the late 1830s, included the following words: “‘Andy,’ said she, (she always called me Andy,) ‘you are going to a new country, and among a rough people; you will have to depend on yourself and cut your own way through the world. I have nothing to give you but a mother’s advice. Never tell a lie, nor take what is not your own, nor sue anybody for slander or assault and battery. Always settle them cases yourself!”’[3]

Elizabeth Jackson set out for Charleston, most likely riding a horse and carrying supplies, in company with two or more other women whose relatives were also held by the British. In Charleston, Mrs. Jackson sought out her two nephews, Joseph and William Crawford, who were confined aboard a prison ship in the harbor. The paucity of extant records from that era renders it impossible to determine which prison ship she visited, or where in the harbor it was moored.[4] Thanks to the survival of post-war service records, however, we know that Joseph had “died in prison” several months earlier, but William was still alive.[5]

Elizabeth Jackson set out for Charleston, most likely riding a horse and carrying supplies, in company with two or more other women whose relatives were also held by the British. In Charleston, Mrs. Jackson sought out her two nephews, Joseph and William Crawford, who were confined aboard a prison ship in the harbor. The paucity of extant records from that era renders it impossible to determine which prison ship she visited, or where in the harbor it was moored.[4] Thanks to the survival of post-war service records, however, we know that Joseph had “died in prison” several months earlier, but William was still alive.[5]

Elizabeth Jackson apparently visited her nephew and his fellow prisoners aboard some unknown vessel, where she contracted an infection that produced a fever. Numerous biographers of the seventh president have described her sickness variously as cholera, plague, yellow fever, smallpox, and “ship fever,” but its precise identity is unknown. Ship fever, or typhus, is the most likely diagnosis, spread by body lice among people held in close quarters without proper hygiene or sanitation.[6] Elizabeth soon grew ill, and found refuge in the humble household of a young couple who lived on Charleston Neck, just outside of the capital town.

William Barton (died ca. 1806) and his twenty-four-year-old wife, Agnes Barton (1757–1846) had lived in the Waxhaw district near the Jacksons before the war, but moved to the vicinity of Charleston at some point prior to 1781. Agnes was also a native of County Antrim in the old country, and took the ailing Elizabeth Jackson into her home. The fever soon sapped her strength, however, and the mother of the future president died at the Barton home during the summer of 1781. Agnes apparently used her own clothes to dress the corpse, and sent Elizabeth’s clothes to her son. William Barton, a carpenter by trade, provided a coffin and dug a grave somewhere on the Neck, outside the lines of occupied Charleston.[7]

Young Andrew Jackson learned of his mother’s death when the matrons who had accompanied her to Charleston returned to the Waxhaws without her later in 1781. As numerous biographers have written over the past two centuries, the loss of Jackson’s family during the American Revolution had a profound impact on his emotional development. He apparently spoke of his mother often throughout his life and recalled the harsh lessons she had instilled in him during childhood. Jackson later lamented that he did not know the location of her grave, and could not honor her bones with a proper memorial. He recounted to later friends that he had gone to Charleston shortly after the British evacuation and spent many reckless weeks betting on horse races and games of chance. Whether or not he searched for his mother’s grave during that sojourn is unclear, but the mystery surrounding her final resting place haunted him for many years.

In early August 1824, while residing at his home in Nashville, Tennessee, Andrew Jackson received a letter from a stranger in the old Waxhaw community of South Carolina. The writer was James Hervey Witherspoon (1784–1842) of Cane Creek, Lancaster County, who informed the presidential candidate that he had just named his newborn son Andrew Jackson Witherspoon to honor the man he considered an American hero. General Jackson was still fondly remembered in the neighborhood, but the writer asked if the general could confirm whether he had been born in North or South Carolina. Old Mrs. Barton, at whose home Elizabeth Jackson had died in 1781, still lived in the Waxhaw neighborhood, said Mr. Witherspoon, and they all wished him well.[8]

This brief mention of Jackson’s mother and the survival of a woman who witnessed her death sparked immediate interest in Nashville. The general composed a short reply on August 11th, 1824, which survives among Jackson’s papers at the Library of Congress and was published in the early twentieth century. Because this letter contains details of great importance to this story, we need to hear a few lines of Jackson’s reply:

“As to the question asked, I with pleasure answer, I was born in So Carolina, as I have been told at the plantation whereon James Crawford lived about one mile from the Carolina road of the Waxhaw Creek, left that state in 1784, was born on the 15 of March in the year 1767.

I am truly happy to learn, at what house my mother died, I knew she died near Charleston, having vissitted [sic] that city with several matrons to afford relief to our prisoners with the British—not her son as you suppose, for at that time my two elder brothers were no more; but two of her nephews, William and Joseph Crawford sons of James Crawford then deceased.

I well recollect one of the matrons that went with her was Mrs. Boyd. It is possible Mrs. Barton can inform me where she was buried that I can find her grave. This to me would be great satisfaction, that I might collect her bones and inter them with that of my father and brothers.”[9]

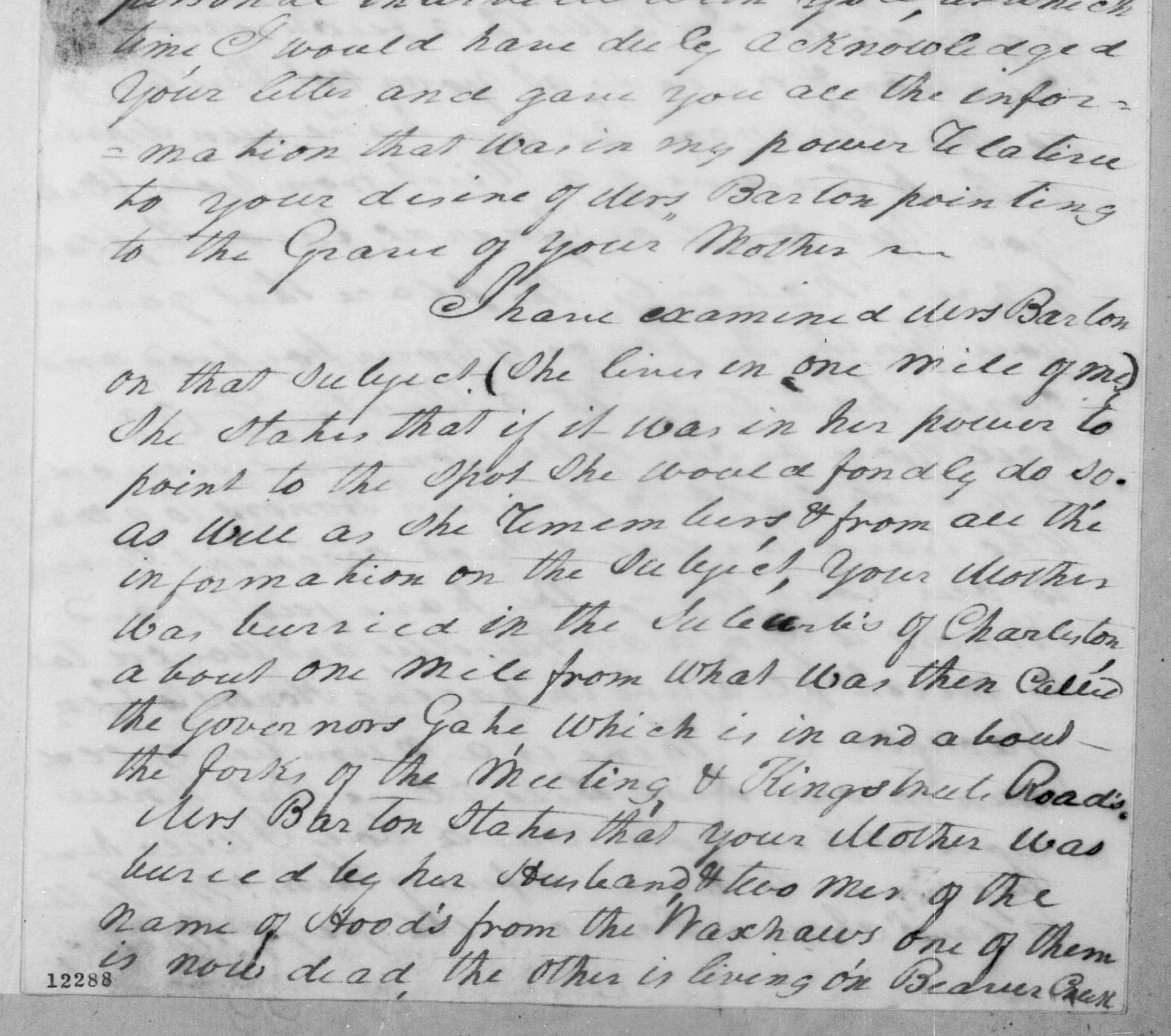

James Witherspoon did not immediately reply to Jackson’s request because he hoped the general might soon return to South Carolina and provide an opportunity to converse in person. After a delay of six months, however, Witherspoon finally put pen to paper and composed a letter in April 1825 that also survives among the Jackson papers at the Library of Congress and was likewise published in the early twentieth century. Relative to the location of the grave of Elizabeth Jackson in 1781, Mr. Witherspoon conveyed the following information (with his original spelling):

James Witherspoon did not immediately reply to Jackson’s request because he hoped the general might soon return to South Carolina and provide an opportunity to converse in person. After a delay of six months, however, Witherspoon finally put pen to paper and composed a letter in April 1825 that also survives among the Jackson papers at the Library of Congress and was likewise published in the early twentieth century. Relative to the location of the grave of Elizabeth Jackson in 1781, Mr. Witherspoon conveyed the following information (with his original spelling):

“I have examined Mrs. Barton on that subject, (she lives in one mile of me)[.] She states that if it was in her power to point to the spot she would fondly do so; as well as she remembers, and from all the information on the subject, your mother was burried in the suburb’s of Charleston, about one mile from what was then called the Governors Gate, which is in and about the forks of the Meeting and Kingstreet Road’s.

Mrs. Barton states that your Mother was buried by her husband, & two men of the name of Hood’s from the Waxhaws[;] one of them is now dead, the other is living on Beaver Creek. Mrs. B. is of the opinion that after so long a time of nearly fifty years, she would have no knowledge of the particular spot, but she is of the opinion that Mr. Hood can point to the place for he has frequently in conversation with Mrs. B. told her, that he often has noticed the little house where they all lived in passing to Charleston with his waggon, and spoke of your mother etc. I would have long ere this have called on Mr. Hood, who lives about 12 or 15 miles from me, for information, but defered it untill you would come out, when you would have seen him yourself; but the first good opportunity, I will see him.”[10]

James Witherspoon’s 1825 description of Elizabeth Jackson’s gravesite, obtained from Agnes Barton more than forty years after Mrs. Jackson’s death, represents the most reliable extant source of information about this topic. Because it contains rather vague geographic directions, however, it is not possible to locate or mark the burial site on the modern landscape. Nevertheless, we can parse Witherspoon’s sparse text in an effort to establish some general conclusions.

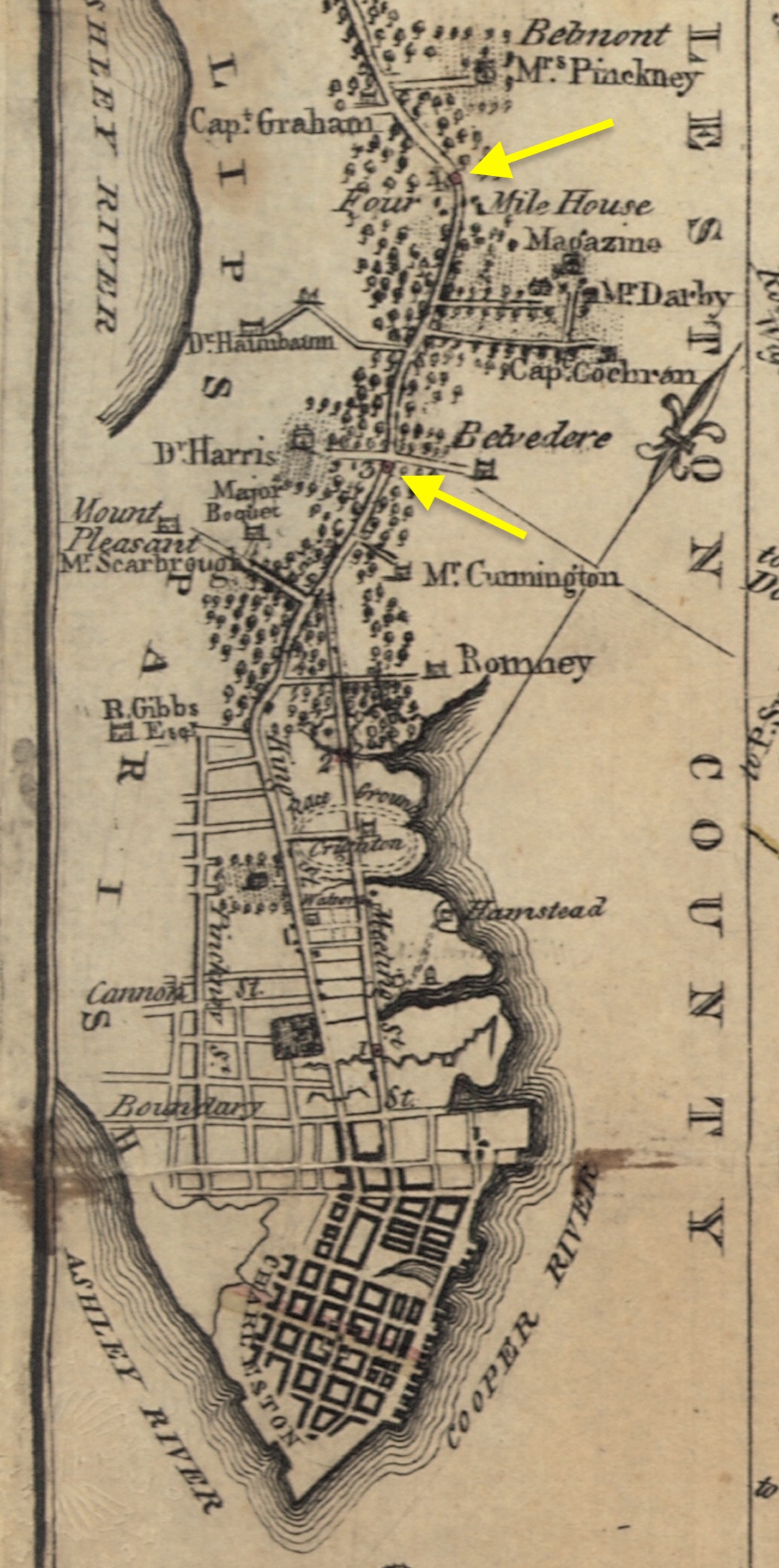

First, the 1825 letter makes it clear that that Elizabeth Jackson was buried outside of Charleston proper, in the “suburbs.” Charleston was still an unincorporated town in 1781, but the nominal town boundary was then Boundary Street, established in 1769 (see Episode No. 80). We can deduce that Mrs. Jackson was not buried anywhere near Boundary Street (now called Calhoun Street), however, because Witherspoon’s letter refers next to the forks of King Street and Meeting Street. King Street was originally the sole road continuing north of the town and up the Neck, but, during the winter of 1786, Meeting Street was extended northward in a straight line until it intersected with King Street at a point almost precisely two miles north of Calhoun Street. Northward of that intersection or fork, as Agnes Barton called it, the ancient pathway once known as the Broad Path became Meeting Street Road (see Episode No. 81).

Next, the 1825 letter mentions one specific geographic landmark—“Governors Gate.” This phrase, once familiar to generations of Charlestonians, faded out of the local lexicon in the years after the American Revolution, but survives in newspaper notices from the second half of the eighteenth century. Governor’s Gate once marked the entrance to a smallish plantation (circa 144 acres) on the east side of Charleston Neck, immediately north of the plantation known as Magnolia Umbra (now Magnolia Cemetery). The provincial government purchased that site around the year 1712 and erected a house for the use of the successive governors of South Carolina. It was long known as the Governor’s house, though it was occasionally vacant. The entire tract was sold to the Shubrick family around 1767 and renamed Belvedere Plantation. Belvedere became the home of the Charleston Country Club at the beginning of the twentieth century, and later became a refinery site for the Standard Oil Company.[11]

Next, the 1825 letter mentions one specific geographic landmark—“Governors Gate.” This phrase, once familiar to generations of Charlestonians, faded out of the local lexicon in the years after the American Revolution, but survives in newspaper notices from the second half of the eighteenth century. Governor’s Gate once marked the entrance to a smallish plantation (circa 144 acres) on the east side of Charleston Neck, immediately north of the plantation known as Magnolia Umbra (now Magnolia Cemetery). The provincial government purchased that site around the year 1712 and erected a house for the use of the successive governors of South Carolina. It was long known as the Governor’s house, though it was occasionally vacant. The entire tract was sold to the Shubrick family around 1767 and renamed Belvedere Plantation. Belvedere became the home of the Charleston Country Club at the beginning of the twentieth century, and later became a refinery site for the Standard Oil Company.[11]

From this information, we can determine that Agnes Barton correctly remembered in 1825 that the old Governor’s Gate was indeed located “in and about” the vicinity of the intersection of King Street and Meeting Street. On the modern landscape, the closest approximation to the old entrance to Belvedere Plantation is the present Greenleaf Road, which is approximately one-third of a mile north of the forks mentioned by Mrs. Barton.

But there’s another reason why Agnes Barton remembered the Governor’s Gate more than forty years after the burial of Elizabeth Jackson. At that site once stood a stone marker indicating that it was the three miles further down Meeting Street to the courthouse at the intersection of Broad and Meeting Streets. This three-mile stone, like the other mile-markers that once stood along this public highway, it long gone, but it was once a conspicuous landmark that helped travelers judge their progress between town and country.[12]

Finally, the woman who helped bury Elizabeth Jackson in 1781 recalled that the grave was located “about one mile from” the Governor’s Gate. Although she did not specify the direction from the gate in question, logic dictates that she meant one mile further along the sole highway leading northward up Charleston Neck. One mile north of the three-mile stone leads, of course, to the site of the four-mile stone. During much of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a roadside tavern known as the Four Mile House stood here, adjacent to a broad bend in the old roadway, offering refreshment for weary travelers. The tavern is long gone now, but the four-mile stone is now in the museum of the South Carolina Historical Society. On the site of what was once a bucolic landscape of suburban Charleston but is now a sparse industrial zone, one can still find a short stub of a street called Four Mile Lane on the east side of Meeting Street Road (click here to see a map). Somewhere in this vicinity we might find the final resting place of Elizabeth Jackson.[13]

In various biographies of President Andrew Jackson published during the second half of the nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth century, writers unfamiliar with the landscape of Charleston in the 1780s have misinterpreted the clues pointing to the site of Elizabeth Jackson’s grave and posited a broad range of geographic guestimates. This confusion took root here in Charleston as well, when local residents sought to honor the president’s mother by erecting a stone in her memory and argued about the proper location.

A newspaper story titled “Elizabeth Jackson, War Mother,” published locally in January 1942, inspired five soldiers stationed at Fort Moultrie to pool their money and purchase a granite memorial.[14] Drawing details from a popular biography of President Jackson published in 1933, the soldiers crafted an inscription that acknowledged Mrs. Jackson’s death in 1781 and the parting words of advice she gave to her son. The biography in question, written by Maquis James, asserted without evidence that Mrs. Jackson had died in November 1781, and paraphrased Agnes Barton’s 1825 description of Elizabeth’s grave site. The Charleston soldiers of 1942 partially understood the geographic description, but were unfamiliar with the meaning of the phrase “Governor’s Gate.” As a result, they simply placed their memorial stone near the forks of Meeting Street and King Street Roads. More specifically, the Jackson memorial of 1942 was located on the east side of the King Street Extension (created in 1926), just a few feet south of Heriot Street.[15]

The memorial stone erected in 1942 stood alone on the roadside for the next twenty five years, outside of Charleston’s city limits and divorced from any other landmark or place of historical interest. Its creators left the Charleston area during World War II and the survivors were disappointed during later visits to find the stone neglected, battered, and covered with weeds. The state Highway Department said that the monument was outside their jurisdiction and refused to be responsible for its maintenance. It stood on land owned by the Southern Railway Company, but railroad officials said they had not given permission for its installation and refused to be responsible for its maintenance.[16]

The memorial stone erected in 1942 stood alone on the roadside for the next twenty five years, outside of Charleston’s city limits and divorced from any other landmark or place of historical interest. Its creators left the Charleston area during World War II and the survivors were disappointed during later visits to find the stone neglected, battered, and covered with weeds. The state Highway Department said that the monument was outside their jurisdiction and refused to be responsible for its maintenance. It stood on land owned by the Southern Railway Company, but railroad officials said they had not given permission for its installation and refused to be responsible for its maintenance.[16]

In the early 1950s, the local Daughters of the American Revolution sought to bolster the memory of Elizabeth Jackson by moving the 1942 memorial stone to what they considered a more historically appropriate location within the city limits. The DAR asked permission from the surviving soldiers to relocate the stone to Washington Square, just behind City Hall, where it might be seen by throngs of tourists and easily maintained by local residents. The soldiers refused, however, insisting that Mrs. Jackson’s grave was most likely near the forks of Meeting Street and King Street. Frustrated by this disagreement, the DAR obtained permission from the city to erect a new monument in Washington Square. The text of that granite stone, which was unveiled in April 1954 and still stands in north end of that park near Chalmers Street, recalls vaguely that the president’s mother “gave her life in the cause of independence while nursing revolutionary soldiers in Charles Town and is buried in Charleston.”[17]

Despite the creation of a new memorial in the heart of the city, locals and visitors continued to lament the neglected condition of the 1942 marker. A member of the Hermitage Association, President Jackson’s museum house in Tennessee, even threatened to pay for the stone’s removal if it didn’t receive more care. “As it stands now,” said Margaret Wright in the summer of 1955, “it is a blot on this courageous woman’s memory.”[18] Local frustration reached a climax during the early months of 1967, which year marked the bicentennial of Andrew Jackson’s birth. As both North and South Carolina prepared to open new state parks in honor of the seventh president, a number of Charlestonians pulled together to move the stone placed on the Neck in 1942.

Local writer Frank Gilbreth, who used the pen name Ashley Cooper, was the chief agitator in the 1967 effort to move the Jackson memorial. Through his popular newspaper column, “Doing the Charleston,” Gilbreth initially chastised the soldiers of 1942 who erected the stone for their lack of knowledge about the city’s historical geography. Joined by local historian Samuel G. Stoney, he proposed that the marker belonged somewhere along Calhoun Street, which marked the city limit during the era of the American Revolution. One of the surviving soldiers, Dr. Neill Macaulay of Columbia, supported by the opinion of state historian Alexander Salley, maintained that the forks of the Meeting Street and King Street roads was the appropriate location. Both sides admitted their errors, however, when others in the community offered a more nuanced interpretation of the documentary evidence. The Governor’s Gate, they learned, referred to the old Belvedere Plantation, and Mrs. Jackson’s burial site was supposed to be one mile beyond that location.[19]

Local writer Frank Gilbreth, who used the pen name Ashley Cooper, was the chief agitator in the 1967 effort to move the Jackson memorial. Through his popular newspaper column, “Doing the Charleston,” Gilbreth initially chastised the soldiers of 1942 who erected the stone for their lack of knowledge about the city’s historical geography. Joined by local historian Samuel G. Stoney, he proposed that the marker belonged somewhere along Calhoun Street, which marked the city limit during the era of the American Revolution. One of the surviving soldiers, Dr. Neill Macaulay of Columbia, supported by the opinion of state historian Alexander Salley, maintained that the forks of the Meeting Street and King Street roads was the appropriate location. Both sides admitted their errors, however, when others in the community offered a more nuanced interpretation of the documentary evidence. The Governor’s Gate, they learned, referred to the old Belvedere Plantation, and Mrs. Jackson’s burial site was supposed to be one mile beyond that location.[19]

No one writing in 1967 proposed to move the memorial stone to the geographically appropriate spot on Charleston Neck, which was then an industrial brown zone populated by junkyards, dive bars, and gentlemen’s clubs catering to the enlisted men stationed at Charleston Navy Yard. Instead, the agitators agreed to accept an invitation from Walter R. Coppedge, President of the College of Charleston, who offered to host the 1942 memorial stone on the school’s newly-landscaped Cougar Mall. Without ceremony in August 1967, the twenty-five-year-old marker quietly moved to its new home just a few yards south of Calhoun Street, a short distance west of St. Philip Street, where it still stands today.[20]

Over the past fifty-odd years, thousands of students and visitors have walked past the marker dedicated to Elizabeth Jackson and read the words inscribed in granite in 1942: “Near this spot is buried Elizabeth Jackson, mother of Andrew Jackson, she gave her life cheerfully for the Independence of her country, on an unrecorded date in Nov. 1781, and to her son Andy this advice: ‘Andy, never tell a lie, nor take what is not your own, nor sue for slander, settle those cases yourself.’”

During the past half-century, however, those pausing to read the brief story of Elizabeth Jackson have left the scene with the mistaken impression that the president’s mother was interred somewhere on or near the campus of the College of Charleston, in the heart of the city. The truth of the matter is a bit more complicated, as demonstrated by this long-winded podcast, and we need a bite-sized conclusion to offer to future visitors. In closing, I’ll offer a few words for your consideration:

During the past half-century, however, those pausing to read the brief story of Elizabeth Jackson have left the scene with the mistaken impression that the president’s mother was interred somewhere on or near the campus of the College of Charleston, in the heart of the city. The truth of the matter is a bit more complicated, as demonstrated by this long-winded podcast, and we need a bite-sized conclusion to offer to future visitors. In closing, I’ll offer a few words for your consideration:

Elizabeth Hutchinson Jackson, a native of Ireland aged about forty years, came to Charleston in the summer of 1781 to assist captive soldiers who needed a helping hand to get back on their feet. She died shortly after her arrival and was buried by friends at a quiet suburban site approximately three and a half miles north of the granite marker on the campus of the College of Charleston. The precise location of her grave is lost, but two granite markers within the city encourage residents and visitors to recall her legacy. We remember Elizabeth Jackson as the mother of a future president of the United States and as a hero of the American Revolution. Her selfless courage exemplified the sacrifice offered by so many unsung women during this nation’s struggle for independence.

[1] The most egregious example is Augustus C. Buell, History of Andrew Jackson: Pioneer, Patriot, Soldier, Politician, President (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1904).

[2] Hendrick Booraem, Young Hickory: The Making of Andrew Jackson (Dallas: Taylor Trade Publishing, 2001), 108, 253, footnote 5.

[3] W. H. Sparks, The Memories of Fifty Years (Philadelphia: Claxton, Remsen & Haffelfinger, 1870), 147–148.

[4] During the occupation of Charleston between May 1780 and December 1782, British forces at least six vessels of various descriptions during the occupation of Charleston to incarcerate American soldiers. Most of these “prison ships” were transport vessels used temporarily, but there at least one aging warship that later returned to sea and at least one dismasted vessel called a “prison hulk.” See Carl P. Borick, Relieve Us of This Burthen: American Prisoners of War in the Revolutionary South, 1780–1782 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2012), 11–25, 109–10, 119.

[5] Both Joseph and William Crawford were captured at “Sumter’s surprise” on 18 August 1780 (following the Battle of Camden) and imprisoned by British forces. Joseph died in prison on 15 October 1780. See South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Accounts Audited of Claims Growing out of Revolution, File No. 1589, (Joseph Crawford) and No. 1594 (William Crawford).

[6] Booraem, Young Hickory, 109, 254, footnote 9.

[7] See John W. Gaines’s article in Nashville Banner, 18 August 1918, page X5, “Jackson’s Mother’s Grave.” A broadside version of this same text is found on the website of the Library of Congress.

[8] Witherpoon’s letter, dated 24 July 1824, does not survive; my description of it is drawn from the contents of Jackson’s reply of 11 August 1824.

[9] Andrew Jackson to James H. Witherspoon, 11 August 1824, from the Andrew Jackson Papers at the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/maj010588/).

[10] 1 James H. Witherspoon to Andrew Jackson, 16 April 1825, from the Andrew Jackson Papers at the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/maj010703/). This text also appears in John Spencer Bassett, ed., Correspondence of Andrew Jackson, Volume III, 1820–1828 (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1928).

[11] See references to “Governor’s gate” in South Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, 21 October 1766, page 4, “Brought to the Work-House”; South Carolina Gazette and General Advertiser, 18–22 November 1783, supplement, page 2, “Capt. George Cowan”; State Gazette of South Carolina, 4 July 1785, page 3, “Charleston, July 4.” For a brief overview of the governor’s plantation, see Henry A. M. Smith, “Charleston and Charleston Neck: The Original Grantees and the Settlements along the Ashley and Cooper Rivers,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 19 (January 1918): 23–25.

[12] The three-mile stone and other mile-markers appear on Thomas Abernethie’s “Road to Watboo Bridge from Charleston” (Charleston, S.C.: Walker and Abernethie, 1787), a copy of which can be found on the website of the Library of Congress.

[13] Note that the old Four Mile House was distinct from the Quarter House, which was located near the six-mile stone. William Henry Foote, Sketches of North Carolina (New York: Robert Carter, 1846), 199, described Mrs. Jackson burial site as being near the Quarter House, and several subsequent writers repeated that error.

[14] Charleston News and Courier, 26 January 1942, page 4, “Elizabeth Jackson, War Mother”; News and Courier, 28 January 1942, page 4, “Contribution of a Soldier.” The solider in question was Neill Macaulay.

[15] Marquis James, Andrew Jackson, The Border Captain (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1933), 28–29, quoting material from W. H. Sparks, The Memories of Fifty Years (Philadelphia: Claxton, Remsen & Haffelfinger, 1870), 147–148; and John Spencer Bassett, ed., Correspondence of Andrew Jackson, Volume III, 1820–1828 (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1928), 265. The five soldiers responsible for the stone included Neill Maculay, Buck Marks, Joseph E. Wallace, Bob Winchester, and Angus Shealy, who were identified in Charleston Evening Post, 29 September 1947, page 9A, “Veterans Find Marker to Nurse Neglected.”

[16] News and Courier, 1 October 1947, page 10, “Monument to Jackson’s Mother Untended, Nearly Forgotten,” by Jack Leland; News and Courier, 20 October 1947, page 4, letters to the editor, “Mrs. Jackson’s Grave,” by Webber D. Mott.

[17] News and Courier, 11 December 1953, page 14A, “Gus Ballis Addresses DAR Chapter on Citizenship”; City Council proceedings of 12 January 1954, in Evening Post, 18 January 1954, page 9B, “Monument to Elizabeth Hutchinson Jackson”; Evening Post, 23 April 1954, page 2A, “Unveiling Ceremony Scheduled by DAR”; News and Courier, 9 June 1955, page 16A, editorial, “Jackson Monument.”

[18] News and Courier, 9 June 1955, page 16A, Letters to the Editor. . . . Neglected Marker.”

[19] See the “Doing the Charleston” stories by Ashley Cooper (Frank Gilbreth) on page 1B of News and Courier, 23 January, 25 January, 31 January, 10 February, 14 February, and 27 March 1967.

[20] Evening Post, 18 August 1967, page 11A, “Mrs. Jackson’s Monument Moved to College Mall”; News and Courier, 23 August 1967, page 1B, “Doing the Charleston,” by Ashley Cooper (Frank Gilbreth).

NEXT: The Star-Spangled Spirit of Charleston

PREVIOUSLY: The Public Life of Charleston’s Market Hall

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments