The Myth of “Trott’s Cottage”

Processing Request

Processing Request

In a quaint brick structure recessed from the south side of Cumberland Street once lived one of the most famous South Carolinians of the colonial era, Chief Justice Nicholas Trott—so says a century’s worth of tourist literature and newspaper copy. Did the affluent Judge Trott really live in this petit cottage, or is there some flaw in this historical tale? The definitive answer lies buried in the archival record, where we find the details of a romantic story spanning three centuries in the life and times of the site now called “Trott’s Cottage.”

Nicholas Trott (1663–1740) is a well-known and controversial figure in the long history of South Carolina, but let’s review for a moment a brief synopsis of his biography. A native of England, he travelled to Bermuda in his early adult life and then studied law in London in the 1690s. The Lords Proprietors of Carolina appointed Trott attorney general of the colony in early 1698, and he arrived in Charleston the following year. He was also elected to the Commons House of Assembly in 1700 and became Chief Justice of Carolina in 1703. In the course of several return trips to England between 1708 and 1714, Trott curried additional favor with the Lords Proprietors, who enlarged his political powers. He was appointed to the prestigious Governor’s Council in 1714 and in 1716 became judge of the Court of Vice-Admiralty, responsible for adjudicating cases of maritime law.

During his first twenty years in Charleston, Nicholas Trott made few friends and numerous enemies. Besides holding a number of minor offices that provided multiple streams of income, he charged exorbitant fees for his various legal services. A deeply religious man, Trott actively discriminated against all who did not conform to the practices of the Church of England. He held the power to veto any laws passed by the provincial legislature that did not meet his personal approval. He was the sole judge of all the courts of the land, and frequently manipulated the course of justice to suit his personal interests. Besides his judicial monopoly in South Carolina, Nicholas Trott is perhaps best remembered as the judge who tried fifty-eight pirates in late 1718, condemning forty-nine of them to be hanged at White Point (See Episode No. 92). We know many details about that memorable series of trials because Trott sent a transcript of the entire affair to England, where it was published in 1719 under the title The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, and Other Pirates.

Trott’s political and legal abuses enraged many citizens over the years and contributed greatly to the political coup that toppled South Carolina’s government in late 1719 (see Episode No. 140). The revolutionary faction that assumed power that December immediately stripped Trott of all his offices. The fifty-seven-year-old judge then set sail for London, where he lobbied diligently for the preservation of Proprietary rule (and his career) in South Carolina. When the British Crown decided in 1720 to repossess the colony from the Proprietors, Trott was on the losing side of the political coin. He never held office again in South Carolina, though he lived here for another twenty years, until his death in January 1740.[1]

In reading various stories of intrigue and adventure related to early days of Charleston, many people—including me—find enjoyment in learning about the physical settings in which such historical events took place. For this reason, readers and tourists often like to know where and in what manner historical figures once lived in order to imagine more clearly the distant past. So, we might ask, where did Judge Nicholas Trott live during his forty-one years in Charleston? Since the early years of the twentieth century, countless newspaper articles, tourist brochures, and guided walks have informed visitors that the cantankerous chief justice resided in a petit cottage on the south side of Cumberland Street, which has been described as the oldest or one of the oldest brick houses in the city. Let’s take a walk down to that site and investigate the story.

In reading various stories of intrigue and adventure related to early days of Charleston, many people—including me—find enjoyment in learning about the physical settings in which such historical events took place. For this reason, readers and tourists often like to know where and in what manner historical figures once lived in order to imagine more clearly the distant past. So, we might ask, where did Judge Nicholas Trott live during his forty-one years in Charleston? Since the early years of the twentieth century, countless newspaper articles, tourist brochures, and guided walks have informed visitors that the cantankerous chief justice resided in a petit cottage on the south side of Cumberland Street, which has been described as the oldest or one of the oldest brick houses in the city. Let’s take a walk down to that site and investigate the story.

The house presently identified as No. 83 Cumberland Street is a charming two-story brick residence nestled between the colonial-era Powder Magazine museum to the east and a large twentieth-century apartment building to the west. The house is recessed some fifty feet south of Cumberland street, next to which stands an ornamental iron gate covered with evergreen foliage. Attached to the gate are several bronze plaques identifying the site as “Trott’s Cottage,” one of the oldest houses in Charleston, the former residence of Chief Justice Nicholas Trott, and which is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Unbeknownst to most of the pedestrians who amble past this romantic site, however, none of this information is accurate. Neither Nicholas Trott nor anyone else resided at this site before the 1760s, and the property is not listed on the National Register. The house, like its neighbors, forms part of the Old and Historic District of the City of Charleston, created in 1931 and expanded in later years, but it is definitely not individually identified on the prestigious National Register. The petit brick residence, or “cottage,” does have a history, of course, but its real story is far different from that which locals and tour guides have been repeating for the past century.[2]

The root of all the stories about Nicholas Trott’s supposed residence in Cumberland Street can be traced to one source published in 1819. In his volume of Medical and Philosophical Essays, Dr. John Shecut narrated a tour around the historic landscape of urban Charleston that includes the following statement: “Among the first brick houses built in the town, is that in Cumberland-street, now occupied by Mr. Thorne, immediately opposite to the Episcopal Methodist Church [on the north side of Cumberland Street]. It was the residence of Chief Justice Trott.” Shecut, who trained as a physician rather than as a historian, offers no explanation regarding the source of his spurious assertion about Trott’s residence. His 1819 statement is not supported by any surviving documents created during Trott’s lifetime, and it stands in contradiction to the known facts of the history of Cumberland Street in general.[3]

To complicate the matter even further, twentieth-century readers misidentified the brick house to which Shecut was referring. In 1819, he pointed to the house “occupied by Mr. Thorne” as Trott’s former residence. Thorne’s house was not the small brick structure, recessed some fifty feet south of Cumberland Street, but rather a much larger and grander house that once stood next door, at the site now identified as No. 85 Cumberland Street. Many generations of legal records demonstrate that the small, two-story brick structure at No. 83 Cumberland Street was simply the kitchen house behind and east of the big house that fronted the street. Cumberland Street itself was created in 1747, seven years after the death of Nicholas Trott, and so the main house and its detached kitchen were built sometime later. In short, John Shecut’s 1819 assertion that Nicholas Trott resided in one of the town’s first brick houses in Cumberland Street is complete nonsense. In case anyone is skeptical of my conclusion, I’ll offer you a chain of three centuries of empirical facts.

To complicate the matter even further, twentieth-century readers misidentified the brick house to which Shecut was referring. In 1819, he pointed to the house “occupied by Mr. Thorne” as Trott’s former residence. Thorne’s house was not the small brick structure, recessed some fifty feet south of Cumberland Street, but rather a much larger and grander house that once stood next door, at the site now identified as No. 85 Cumberland Street. Many generations of legal records demonstrate that the small, two-story brick structure at No. 83 Cumberland Street was simply the kitchen house behind and east of the big house that fronted the street. Cumberland Street itself was created in 1747, seven years after the death of Nicholas Trott, and so the main house and its detached kitchen were built sometime later. In short, John Shecut’s 1819 assertion that Nicholas Trott resided in one of the town’s first brick houses in Cumberland Street is complete nonsense. In case anyone is skeptical of my conclusion, I’ll offer you a chain of three centuries of empirical facts.

All of the land encompassing the apartment building at 85 Cumberland Street, the so-called “Trott’s Cottage” at 83 Cumberland, the old Powder Magazine, and the now-vacant parking lot at the southwest corner of Church and Cumberland Streets, formed a single half-acre lot in the original plan of Charleston. The so-called “Grand Model” of the town, created around 1672, identified this property as Lot No. 180, which the provincial government granted to a merchant named Peter Burtell (also spelled Buretell, Brutell) in November 1693.[4] Mr. Burtell acquired a number of other lots in urban Charleston and elsewhere during his lifetime, most of which remained undeveloped until after his death. In his will, made in January 1701 (probably 1701/2), Peter Burtell directed his executors to divide his property, after the death of his wife, equally among their grandchildren. Mr. and Mrs. Burtell died at some point in the early eighteenth century, but the precise dates are now unknown.[5]

In the meantime, South Carolina’s provincial government resolved in December 1703 to build a storehouse or magazine for gunpowder somewhere on the outskirts of Charleston, but within the earthen walls were about to be built around the capital town.[6] Nothing was done about the magazine for nearly nine years, however, and in the summer of 1712 the legislature ratified another law to initiate the construction of the much-needed powder magazine. The text of that law, which survives only as an incomplete manuscript, directed commissioners to build a brick magazine on a piece of vacant land at what was then the northern edge of town.[7] The land in question formed part of Peter Burtell’s Lot No. 180, but the government exercised its right of eminent domain and built the magazine where it saw fit for the defense and security of the community in general.

The magazine of gunpowder that opened in 1713 served an important defensive function for the colony of South Carolina, but its presence on the northern edge of Charleston created problems as the urban population increased and development expanded. No one wanted to build a residence next to a magazine that might explode at any moment, and citizens meeting at the nearby Congregational Church and the new St. Philip’s Church felt uncomfortable worshiping in proximity to the tinderbox. Furthermore, the presence of the public magazine on the private property of the late Peter Burtell prevented his three surviving heirs, now adult women with families of their own, from using their inheritance. To remedy this situation, their respective husbands, Ralph Izard, Nathaniel Broughton, and Paul Mazyck, petitioned the provincial legislature in 1741. The heirs of Burtell could not make an equitable partition of their inheritance, said the husbands, because none of them wanted to be saddled with a useless lot occupied by a dangerous powder magazine. The legislature promised to remove the gunpowder to a new magazine on the northwest side of town, then under construction, after which the Burtell heirs would be empowered to claim their property.[8] When the powder was not removed from the original magazine in a timely fashion, the citizens of Charleston complained to the legislature in 1744 and the heirs submitted another petition in 1745. That January, the government agreed to pay the heirs of Peter Burtell £100 currency annually “for the hire of the magazine until the same shall be delivered into their possession.”[9]

The magazine of gunpowder that opened in 1713 served an important defensive function for the colony of South Carolina, but its presence on the northern edge of Charleston created problems as the urban population increased and development expanded. No one wanted to build a residence next to a magazine that might explode at any moment, and citizens meeting at the nearby Congregational Church and the new St. Philip’s Church felt uncomfortable worshiping in proximity to the tinderbox. Furthermore, the presence of the public magazine on the private property of the late Peter Burtell prevented his three surviving heirs, now adult women with families of their own, from using their inheritance. To remedy this situation, their respective husbands, Ralph Izard, Nathaniel Broughton, and Paul Mazyck, petitioned the provincial legislature in 1741. The heirs of Burtell could not make an equitable partition of their inheritance, said the husbands, because none of them wanted to be saddled with a useless lot occupied by a dangerous powder magazine. The legislature promised to remove the gunpowder to a new magazine on the northwest side of town, then under construction, after which the Burtell heirs would be empowered to claim their property.[8] When the powder was not removed from the original magazine in a timely fashion, the citizens of Charleston complained to the legislature in 1744 and the heirs submitted another petition in 1745. That January, the government agreed to pay the heirs of Peter Burtell £100 currency annually “for the hire of the magazine until the same shall be delivered into their possession.”[9]

South Carolina’s provincial government continued to rent the powder magazine for another year and a half, during which time the surviving heirs of Peter Burtell made a partition of their joint inheritance. In August 1745, they agreed that Magdalene Elizabeth Chataingner Izard would inherit Lot No. 180 and her eldest son, Henry Izard (ca. 1717–1749), would continue to receive the annual rent from the legislature.[10] The government finally transferred the stockpile of gunpowder to a new magazine near Magazine Street in the summer of 1746 and evidently surrended possession of the property to its lawful owners.[11] Nine months later, in the spring of 1747, Henry Izard and three of his neighbors in the vicinity of the old powder magazine each agreed to sacrifice a strip of eleven feet of land to create a twenty-two-foot wide passageway between Church Street and Meeting Street.[12] To commemorate the recent British victory gained by the Duke of Cumberland over Jacobite rebels at the Battle of Culloden, the new public street was named Cumberland Street. (It was widened to its present dimensions in the late 1830s, but that’s another story.)

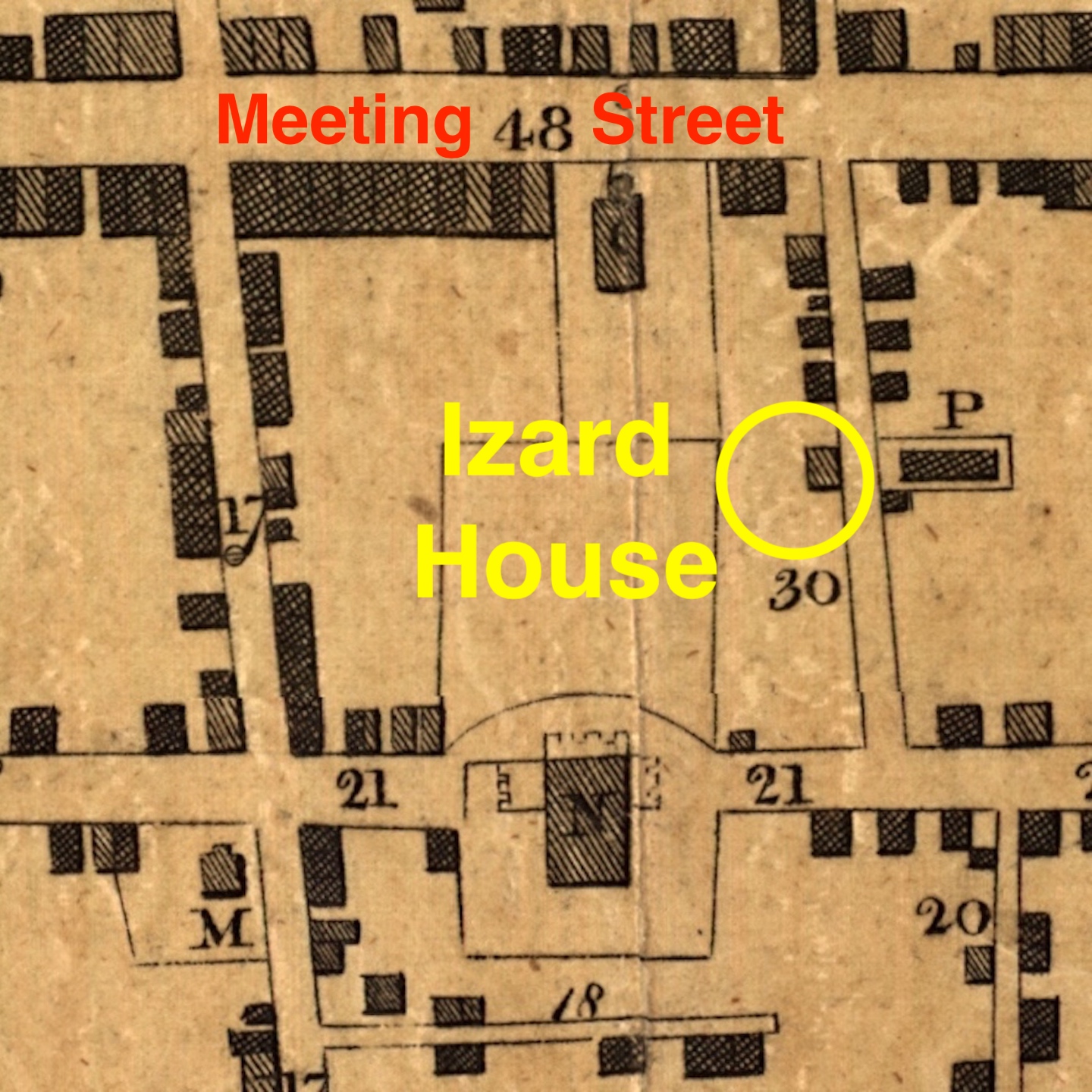

The vacant property surrounding the old powder magazine on the south side of Cumberland Street descended to Ralph Izard (1742–1804), a wealthy South Carolinian who spent most of his early life abroad. After reaching his majority in 1763, apparently, Ralph Izard built a large three-story brick house on the western edge of Lot No. 180, next door to the old powder magazine. The main house measured approximately forty feet wide and twenty-eight feet deep, and stood against the south side of Cumberland Street, in the center of a parcel measuring approximately seventy-five feet wide and nearly 120 feet deep. Behind the house, towards the graveyard of St. Philip’s Church, Izard built several outbuildings, including a detached brick kitchen, carriage house, and stable. All of these buildings were standing and functional by the autumn of 1767, when Izard’s next-door neighbor, Alexander Mazyck, advertised to sell his property on the west end of Cumberland Street “leading to the house of Ralph Izard.” Whether Mr. Izard personally occupied this house or built it as a genteel rental property is unclear, but for the remainder of this conversation I’m going to refer to it “the Izard house.”[13]

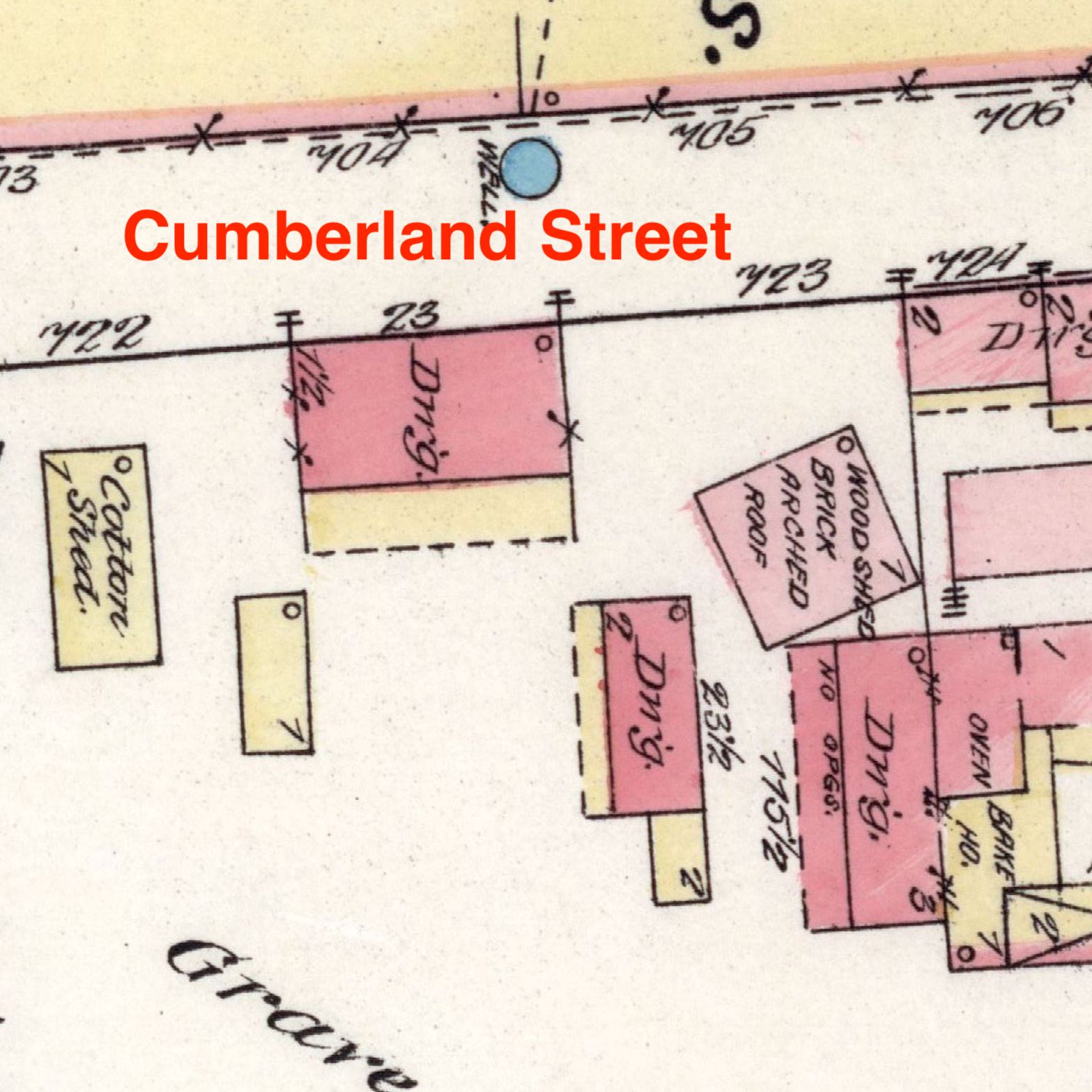

Ralph Izard owned a number of plantations and other properties across South Carolina and beyond, and at the turn of the nineteenth century he began to downsize his property portfolio. In November 1801, Izard sold all of Lot No. 180—including his house and lot on the south side of Cumberland Street—to a “carpenter” named John Lewis Poyas. That transaction included a very useful plat of the property in question. Lot No. 180 included all of the land forming the southwest corner of Church and Cumberland Streets, measuring 127 feet on the west side of Church Street and 269 feet on the south side of Cumberland Street. To the west of the old powder magazine stood the Izard house, a brick structure facing the street to the north with a wooden piazza on the rear facing the south. In the back yard, to the southeast of the main house and closer to the old magazine, appears a smaller rectangle labeled “kitchen of brick.” This detached, recessed brick kitchen, most likely occupied by generations of enslaved servants, is the structure now identified as No. 83 Cumberland Street. In this 1801 plat it is clearly a dependency of the main Izard house fronting the street.[14]

Ralph Izard owned a number of plantations and other properties across South Carolina and beyond, and at the turn of the nineteenth century he began to downsize his property portfolio. In November 1801, Izard sold all of Lot No. 180—including his house and lot on the south side of Cumberland Street—to a “carpenter” named John Lewis Poyas. That transaction included a very useful plat of the property in question. Lot No. 180 included all of the land forming the southwest corner of Church and Cumberland Streets, measuring 127 feet on the west side of Church Street and 269 feet on the south side of Cumberland Street. To the west of the old powder magazine stood the Izard house, a brick structure facing the street to the north with a wooden piazza on the rear facing the south. In the back yard, to the southeast of the main house and closer to the old magazine, appears a smaller rectangle labeled “kitchen of brick.” This detached, recessed brick kitchen, most likely occupied by generations of enslaved servants, is the structure now identified as No. 83 Cumberland Street. In this 1801 plat it is clearly a dependency of the main Izard house fronting the street.[14]

Immediately after purchasing the property in question in 1801, John Lewis Poyas mortgaged it back to Ralph Izard. Poyas couldn’t pay the mortgage, so three years later he released the property back to Izard in May 1804.[15] A few days later, Ralph Izard died suddenly. He didn’t have time to amend his will, so his heirs weren’t sure what to do with the old house on Cumberland Street.[16] After advertising the property for auction in late 1804 and again in the spring of 1806, George Izard of Philadelphia sold the house and lot in August 1809 to John Gardner Thorne (1765–1820) of Charleston, in trust for his wife, Sarah Thorne.[17] The Thorne family was still in residence in the big house on the south side of Cumberland Street when Dr. John Shecut published his 1819 assertion that Nicholas Trott had once lived in the house “now occupied by Mr. Thorne.” Now that we know the real history of that property, we can ignore the good doctor’s pseudo-historical advice.

John Gardner Thorne died in December 1820, but his family continued to reside at the Cumberland Street house for several more years. To facilitate a division of John’s estate, his heirs applied to the Court of Equity, which ordered the house to be sold at auction in August 1824. Advertisements for that sale described the property as “a large, commodious, well-built brick dwelling-house, No. 9, on [the] south side of Cumberland Street, containing ten rooms, with a spacious brick kitchen, all in good repair, carriage house, stable, and all other necessary buildings, with a well of good water , &c. measuring in front, on said street, about 75 feet, and in depth about 120.” The Master in Equity for Charleston District sold the property in September 1824 to Richard Fordham, who acted as trustee for the minor heirs of John Thorne.[18] One of the Thorne heirs married into the clan of attorney Archibald Whitney (1786–1847), who moved his own large family into the old Izard house on Cumberland Street in November 1834. Less than two years later, in April 1836, Richard Fordham formally conveyed the property to Mr. Whitney for the sum of $1 and family affection.[19]

John Gardner Thorne died in December 1820, but his family continued to reside at the Cumberland Street house for several more years. To facilitate a division of John’s estate, his heirs applied to the Court of Equity, which ordered the house to be sold at auction in August 1824. Advertisements for that sale described the property as “a large, commodious, well-built brick dwelling-house, No. 9, on [the] south side of Cumberland Street, containing ten rooms, with a spacious brick kitchen, all in good repair, carriage house, stable, and all other necessary buildings, with a well of good water , &c. measuring in front, on said street, about 75 feet, and in depth about 120.” The Master in Equity for Charleston District sold the property in September 1824 to Richard Fordham, who acted as trustee for the minor heirs of John Thorne.[18] One of the Thorne heirs married into the clan of attorney Archibald Whitney (1786–1847), who moved his own large family into the old Izard house on Cumberland Street in November 1834. Less than two years later, in April 1836, Richard Fordham formally conveyed the property to Mr. Whitney for the sum of $1 and family affection.[19]

Archibald Whitney died in the summer of 1847 and left all of his property to his wife, Mary.[20] The earliest surviving property assessment records for the City of Charleston, dating to 1852, describe this property as a three-story brick dwelling and “yard” held in trust by Mary Whitney.[21] Her house and outbuildings were in the path of the great fire that burned diagonally across the Charleston peninsula in December 1861 and were definitely impacted to some unknown degree. The extent of the damage is unclear, but post-Civil War records describe Mary Whitney’s residence as a two-story brick structure.[22] In the hard economic times that followed the destructive war and fire, Mary began renting her detached kitchen house as a separate residence in order to make ends meet. From the 1870s through the early years of the twentieth century, the newspapers and city directories of Charleston record the names of a series of tenants who transformed the two-story brick kitchen into a hospitable but modest home. In the 1870s and early 1880s, the big Izard house was called No. 23 Cumberland Street, while the detached kitchen was called No. 23 ½. By 1888, the big house was No. 27 and the kitchen No. 25.[23]

In her twilight years, Mary Whitney (1793–1881) began to think about the future of her home and family. In the summer of 1878, Mary conveyed the old family residence to her two unmarried adult daughters, Margaret and Placidia.[24] After Mary’s death in 1881, her daughters continued to live in the big house until the great earthquake that shook Charleston on August 31st, 1886. A structural report of damages across the city includes a description of the two-story Whitney house at 27 Cumberland Street. The upper part of the north wall, facing the street, had collapsed down to the base of the upper windows; the west wall was cracked, and the east wall was unsalvageable. Margaret and Placidia had little income for major repairs and renovations, so they were forced to cut a few corners. In the years after the earthquake, various records consistently describe the Whitney property as a one-story brick structure flanked by a recessed, two-story kitchen house that was rented as a separate residence.[25]

In her twilight years, Mary Whitney (1793–1881) began to think about the future of her home and family. In the summer of 1878, Mary conveyed the old family residence to her two unmarried adult daughters, Margaret and Placidia.[24] After Mary’s death in 1881, her daughters continued to live in the big house until the great earthquake that shook Charleston on August 31st, 1886. A structural report of damages across the city includes a description of the two-story Whitney house at 27 Cumberland Street. The upper part of the north wall, facing the street, had collapsed down to the base of the upper windows; the west wall was cracked, and the east wall was unsalvageable. Margaret and Placidia had little income for major repairs and renovations, so they were forced to cut a few corners. In the years after the earthquake, various records consistently describe the Whitney property as a one-story brick structure flanked by a recessed, two-story kitchen house that was rented as a separate residence.[25]

The spinster sisters had borrowed money from friends to salvage their family home, but they had no income—other than rent from the kitchen house—with which to repay their debts. In August 1901, Margaret and Placidia Whitney signed an agreement with their creditors to settle their worldly affairs. Benjamin H. Rutledge and his wife, Emma, had loaned substantial sums of money to the elderly sisters over the years to repair and maintain their properties. To repay the various sums and to acknowledge their gratitude, the Whitney sisters agreed that Mr. and Mrs. Rutledge should have their Cumberland Street property after their respective deaths.[26]

At that same moment next door, the local chapter of the Society of Colonial Dames was working behind the scenes to purchase the old brick powder magazine on Cumberland Street that had first opened in 1713. The Colonial Dames completed their purchase in 1902 and immediately set a plan in motion to convert the dilapidated structure into a colonial-themed museum. To raise awareness about this plan, the society sponsored an essay contest among the young ladies at Memminger Normal School. The assigned theme was the “History and Romance of the Old Powder Magazine.” When the Honorable T. W. Bacot took the podium at Thomson Auditorium to award the prize to Miss Etta Gertrude Trott in June 1902, he regaled the audience with a retelling of the legend that Chief Justice Nicholas Trott had once lived next door to the old powder magazine, in “a brick building (now owned and occupied by the Misses Whitney).” It’s unclear, however, whether Mr. Bacot was referring to the big house fronting Cumberland Street, once a grand three-story edifice but then much reduced, or the recessed two-story brick kitchen.[27] In either case, the newspaper report of T. W. Bacot’s romantic tale appears to have sparked a trend in local storytelling. The story of Nicholas Trott living in the old brick house next door to the Powder Magazine museum was repeated by locals and newspaper stories for many decades. In the early years of the twentieth century, however, it was unclear which of the two brick structures owned by the Whitney sisters was the residence of the old chief justice.

The confusion over the precise identity of Nicholas Trott’s purported residence in Cumberland Street was either settled or made worse, depending on your perspective, by a chain of events in the second decade of the new century. Margaret Gardner Whitney died in June 1908, and her sister, Placidia Emma Whitney, died in February 1911.[28] Shortly after their deaths, Benjamin and Emma Rutledge joined with Leah Whitney, the last surviving family heir, to dispose of the property that had been in the family for a century. In August 1911, the three executors sold the entire lot, including the main house called No. 27 Cumberland Street and the detached kitchen house called No. 25, to the Cameron and Barkley Company of Charleston.[29] A year later, that company sold it to the Carolina-Florida Realty Company, which performed a few repairs to the main house before transferring the entire property to the General Asbestos and Rubber Company (commonly known as Garco). In late 1916, Garco obtained a permit to demolish the one-story remnant of the 1760s Izard house and construct a large three-story factory on the site.[30] That factory building, later expanded and used as office space for the Federal Emergency Relief Agency in the late 1930s, was converted into apartments in late 1943. The apartments within that massive structure are now condos, and it’s now called No. 85 Cumberland Street.[31]

The confusion over the precise identity of Nicholas Trott’s purported residence in Cumberland Street was either settled or made worse, depending on your perspective, by a chain of events in the second decade of the new century. Margaret Gardner Whitney died in June 1908, and her sister, Placidia Emma Whitney, died in February 1911.[28] Shortly after their deaths, Benjamin and Emma Rutledge joined with Leah Whitney, the last surviving family heir, to dispose of the property that had been in the family for a century. In August 1911, the three executors sold the entire lot, including the main house called No. 27 Cumberland Street and the detached kitchen house called No. 25, to the Cameron and Barkley Company of Charleston.[29] A year later, that company sold it to the Carolina-Florida Realty Company, which performed a few repairs to the main house before transferring the entire property to the General Asbestos and Rubber Company (commonly known as Garco). In late 1916, Garco obtained a permit to demolish the one-story remnant of the 1760s Izard house and construct a large three-story factory on the site.[30] That factory building, later expanded and used as office space for the Federal Emergency Relief Agency in the late 1930s, was converted into apartments in late 1943. The apartments within that massive structure are now condos, and it’s now called No. 85 Cumberland Street.[31]

Throughout these changes to the site in the early twentieth century, the old kitchen house in the shadow of the new Garco factory survived and began a new life as a clearly-independent property. Its original entrance faced to the west, into the yard behind the Izard house, but its new owners moved the door to the north, facing Cumberland Street, and enlarged the windows to gentrify its humble façade. After the removal of the remnants of the Izard-Whitney house in 1916, the legend of Nicholas Trott’s early residence in Cumberland Street focused on the only surviving structure adjacent to the Powder Magazine museum—the old kitchen house, recessed some fifty feet south of the street. As the decades progressed, the fanciful tale of South Carolina’s cantankerous chief justice living here in “the oldest brick house in Charleston” matured into a staple yarn of the tourist trade.[32] The name “Trott’s Cottage” appeared at some point in the late twentieth-century, probably as a marketing slogan, and persists to this day.

Having how heard the long chain of events related to the property now called No. 83 Cumberland Street, I hope you’ll join me in concluding that the legend of “Trott’s Cottage” is simply a myth. I’ll admit that it’s a good story, but the available facts prove it to be nothing more than a figment of the imagination. Nicholas Trott did own and occupy a house in Charleston, but it was not at this site. After a long stretch of tedious detective work, I have indeed found the real location of Judge Trott’s residence. The house is now completely gone, but a bit of Dr. Trott’s literary trash survives at a site that most everyone in Charleston has visited before, approximately 600 feet southeast of Cumberland Street. Tune in next week when I’ll lead you back in time to visit the real residence of Chief Justice Nicholas Trott and plumb the depths of his personal privy.

[1] Walter Edgar and N. Louise Bailey, eds., Biographical Directory of the South Carolina House of Representatives, volume 2 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1977), 681–84; John E. Douglass, “Impeaching the Impeachment: The Case of Chief Justice Nicholas Trott of South Carolina,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 94 (April 1993): 102–16.

[2] The plaques at 83 Cumberland Street are located on private property, and the owner of that property has the right to say whatever he or she wishes about the history of their property. The City of Charleston’s Commission on History is authorized to determine the language of plaques placed on public property, or within the public right-of-way within the city, but the commission has no jurisdiction on private property.

[3] J. L. E. W. Shecut, Shecut’s Medical and Philosophical Essays (Charleston, S.C.: A. E. Miller, 1819), 6.

[4] Susan Baldwin Bates and Harriott Cheves Leland, eds., Proprietary Records of South Carolina, Volume Three: Abstracts of the Records of the Surveyor General of the Province, Charles Towne 1678–1698 (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2007), 78.

[5] The will of Peter Burtell is not extant, but it was described in a conveyance from Alexander Mazyck to Benjamin Simmons on 5 March 1768, recorded in the office of the Charleston County Register of Deeds (hereafter RoD), book I3: 451–56.

[6] See section XIV of Act No. 217, “An Act for making Marriners and Sailers more usefull in time of Allarms, and for Punishing of Victuallers for entertaining of Persons in time of Allarms,” ratified on 23 December 1703, David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 7 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston), 28–33.

[7] See section IX of Act No. 327, “An Additional Act to an Additional Act to an Act entitled an Act for repairing and Expeditious finishing of the Fortifications of Charles Town, and Johnson's Fort, and for putting the said Fortifications in Repair and good order, and Sustaining the Same; and for Building a Publick Magazin [sic] in Charles Town, and for appointing a Powder Receiver and Gunner,” ratified on 7 June 1712. This act was not included in the published Statutes at Large of South Carolina, but part of the text survives in Nicholas Trott’s manuscript “New Collection” among the engrossed statutes at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia (hereafter SCDAH).

[8] J. H. Easterby, ed., The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, September 12, 1739–March 26, 1741 (Columbia: State Commercial Printing Company for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1953), 512, 515.

[9] J. H. Easterby, ed., The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, September 14, 1742–January 27, 1744 (Columbia: South Carolina Archives Department, 1954), 542; J. H. Easterby, ed., The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, February 20, 1744–May 25, 1745 (Columbia: South Carolina Archives Department, 1955), 291–92, 304.

[10] Deed of partition, 8 August 1745, RoD CC: 474–78; Langdon Cheves, “Izard of South Carolina,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 2 (July 1901): 209–15.

[11] J. H. Easterby, ed., The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, September 10, 1745–June 17, 1746 (Columbia: South Carolina Archives Department, 1956), 201, 209, 240. South Carolina Act No. 755, an annual tax bill covering government expenses from 25 March 1746 to 25 March 1747, includes a payment of £33.6.8 to Henry Izard for four months' rent of the "old magazine" (see the engrossed manuscript act at SCDAH). This short-term payment indicates that the government use of the property ended in late July 1746, after the removal of the gunpowder to the newly-completed magazine on the west side of town.

[12] Agreement between the owners of town Lot Nos. 174, 175, 179, and 180, 30 April 1747, RoD CC: 489–90.

[13] The Izard house was described as a three-story structure in auction advertisements in Charleston City Gazette, 12 November 1804, page 2; Charleston Courier, 11 April 1806, page 4; and in the City of Charleston Tax Assessment records of 1852, Ward 3, page 6, held in the Charleston Archive at CCPL; the dimensions of the house were noted in Contains Report of Committee on Condition of Buildings after the Earthquake, with a List of Buildings that Should Come Down (Atlanta, Ga.: Winham & Lester, 1886), 47; South Carolina and American General Gazette, 18–25 September 1767. It is possible that Henry Izard built the house, or began to build the house, sometime after the removal of gunpowder in 1746 and his death in 1749. An examination of extant Izard family papers might clarify definitively whether Henry or his son Ralph Izard built the house in question

[14] Ralph Izard, esquire, to John Lewis Poyas, carpenter, lease and release, 9–10 November 1801, RoD F7: 102–3, 115–17.

[15] John Lewis Poyas, carpenter, to Ralph Izard, mortgage, 10 November 1801, RoD L7: 298–302; John Lewis Poyas to Ralph Izard, release of right of redemption and assignment of mortgage, 10 May 1804, RoD L7: 302.

[16] The will of Ralph Izard, dated 30 December 1799 and proved on 15 June 1804, appears in SCDAH, Will Book 1800–1807; and in WPA transcript volume 29B: 656–62.

[17] City Gazette, 12 November 1804, page 2; Courier, 11 April 1806, page 4; George Izard to John G. Thorne for Sarah Thorne, conveyance in fee and renunciation of dower, 2 August 1809, RoD X7: 436–37.

[18] City Gazette, 19 August 1824, page 3, “Under Decree in Equity”; Master in Equity (William H. Gibbes) to Richard Fordham [Jr.], conveyance, 14 September 1824, RoD book N9: 282–85.

[19] Courier, 21 November 1834, page 3, “Removal”; Richard Fordham to Archibald Whitney, conveyance, 4 April 1836, RoD book O10: 148–50.

[20] The will of Archibald Whitney, dated 26 June 1846, and proved on 24 June 1847, is found in SCDAH, Will Book K (1845–1851), 121, and in WPA transcription volume 44: 202–3 at CCPL.

[21] City of Charleston Tax Assessment records of 1852 held at CCPL, Ward 3, page 6.

[22] The summary of fire “losses” printed in Charleston Mercury, 21 December 1861, page 4, includes “Cumberland Street, South Side, Ward No. 3. . . . [Number] 15 Tr[ust]. Est[ate]. Mrs. M. W. Whitney, [occupied by] Mrs. Mary W. Whitney.”

[23] See the Lamblé plat (created 1882–83), Ward 3, sheet 35, in the Charleston Archive at CCPL; Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of Charleston, 1884, page 11; 1888, page 8.

[24] Mary A. Whitney to Margaret G. Whitney and Placidia Emma Whitney, conveyance, 17 July 1878, RoD O17: 171.

[25] Report of Committee on Condition of Buildings after the Earthquake, with a List of Buildings that Should Come Down (Atlanta, Ga.: Winham & Lester, 1886), 47; Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of Charleston, 1888, page 8; 1902, page 59. The Misses Whitney received $850 from the City of Charleston for unspecified repairs to both 25 and 27 Cumberland Street; see the “Records of the Executive Relief Committee for the Earthquake of 1886” at Charleston Archive, CCPL, box 5, folder 1, voucher No. 1794.

[26] Margaret G. Whitney and Placidia E. Whitney to Benjamin H. Rutledge and Emma C. Rutledge, deed in trust, August 1901 (date not specified), RoD H25: 596–98.

[27] Charleston News and Courier, 20 June 1902, page 5, “Memminger Commencement.” For more information about the Colonial Dames and their Powder Magazine museum, see Alan Stello, Arsenal of History: The Powder Magazine of South Carolina (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2013).

[28] News and Courier, 18 June 1908, page 12, “Funeral Notices”; Charleston Evening Post, 23 February 1911, page 6, “Death Notice.”

[29] Benjamin Rutledge, Emma C. Rutledge, and Leah Whitney to the Cameron and Barkley Company, conveyance, 26 July 1911, RoD H25: 598–601.

[30] Evening Post, 12 February 1913, page 11, “Building Permits”; News and Courier, 13 January 1914, page 3, “The Regular Annual Meeting of the stockholders of the General Asbestos and Rubber Company will be held at the office of the company, No. 27 Cumberland street, Charleston, S.C.”; Evening Post, 18 June 1916, page 9, “Building Permits”; Evening Post, 31 October 1916, page 9, “Building Permits”; News and Courier, 6 November 1916, page 3, “Building Permits Issued.”

[31] News and Courier, 9 June 1935, page 3C, “FERA Employs 189 At Headquarters”; News and Courier, 15 October 1943, “City’s Oldest Building and Former Factory to be Converted”; News and Courier, 8 October 1945, page 10, “Do You Know Your Charleston? 85 Cumberland Street.”

[32] News and Courier, 30 August 1937, page 12, “Do You Know Your Charleston? 25 Cumberland Street.”

NEXT: Nicholas Trott’s Forgotten Charleston Residence

PREVIOUSLY: The Advent of Black Suffrage in South Carolina

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments