Passenger Trains between Charleston and Summerville, from the Best Friend to BRT

Processing Request

Processing Request

Automotive congestion is a fact of life on Lowcountry roads in the twenty-first century, while transportation alternatives struggle to gain traction in our community. Mass transit solutions, while popular in larger urban centers, appear to be contrary to our local habits. It might surprise some, however, that antebellum investors who embraced an emerging technology created one of the earliest mass transit corridors in the United States right here in the Charleston-metro area. Present efforts to revive that transit tradition draw inspiration from local history to spark a new era of mobility across the Lowcountry.

One of the most important but least remembered aspects of local transportation history is the commuter railroad that once linked Charleston to Summerville with robust daily service. This rail connection, which was first imagined by local capitalists in the 1820s, became a reality in the 1830s and endured for nearly one hundred and thirty years. During that long era, this inter-urban railroad was the longest and busiest passenger corridor in South Carolina and might have carried millions of customers over its lifetime. Most of the local population has forgotten about this tradition since the Charleston to Summerville rail service evaporated some sixty years ago, but it’s a story worth remembering. A quick survey of its antebellum roots and pre-automobile heyday also provide a historical framework for appreciating the present options for planning the future of Lowcountry transportation.

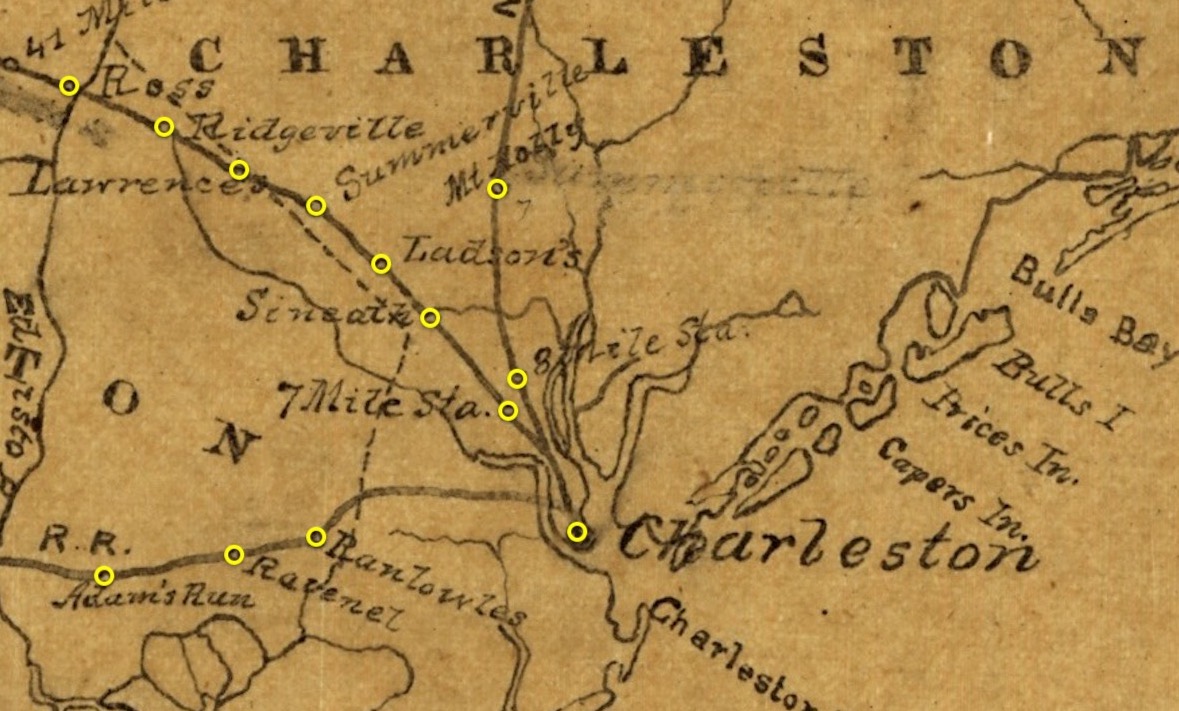

The South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company was chartered in December 1827 and organized in May 1828 for the purpose of building a transportation link between the port city of Charleston and a terminus on the Savannah River called Hamburg (now part of North Augusta). In 1830, the company built a stretch of rail extending six miles up Charleston Neck for demonstration purposes, on which the engine known as the “Best Friend of Charleston” made its debut that December. The work of clearing the route and laying track commenced in earnest in the spring of 1831, proceeding from suburban Charleston to the northwest. Also in 1831, the South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company purchased lands adjacent to the sparsely populated, seasonal village known as Summerville, and began laying out a residential and commercial grid to be known as “new Summerville.” By April of 1832, the railroad began operating service between Charleston and stops at Jericho (nine miles from the city), Sineath’s (twelve miles), and Woodstock (fifteen miles). In early July 1832, the line was extended to include stops at Ladson (seventeen miles from Charleston) and new Summerville (twenty-two miles), with two round-trips operating daily.[1]

The South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company was chartered in December 1827 and organized in May 1828 for the purpose of building a transportation link between the port city of Charleston and a terminus on the Savannah River called Hamburg (now part of North Augusta). In 1830, the company built a stretch of rail extending six miles up Charleston Neck for demonstration purposes, on which the engine known as the “Best Friend of Charleston” made its debut that December. The work of clearing the route and laying track commenced in earnest in the spring of 1831, proceeding from suburban Charleston to the northwest. Also in 1831, the South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company purchased lands adjacent to the sparsely populated, seasonal village known as Summerville, and began laying out a residential and commercial grid to be known as “new Summerville.” By April of 1832, the railroad began operating service between Charleston and stops at Jericho (nine miles from the city), Sineath’s (twelve miles), and Woodstock (fifteen miles). In early July 1832, the line was extended to include stops at Ladson (seventeen miles from Charleston) and new Summerville (twenty-two miles), with two round-trips operating daily.[1]

The advent of daily rail service between Charleston and Summerville in the summer of 1832, carrying both passengers and freight, marked the beginning of a significant era of mass transit and personal mobility that endured for many generations. The Charleston to Hamburg rail line, traversing 136 miles of track, was completed in October 1833, and was briefly the longest commercial railroad in the world. In subsequent years, capitalists organized additional railroad branches that connected the Palmetto City to Columbia, Camden, Savannah, and all points beyond. The frequency of departures between Charleston and local communities increased rapidly as the railroad industry expanded, while improvements in locomotive technology also shortened the duration of each trip.

Also during the second quarter of the nineteenth century, the rise of omnibuses, streetcars, and steam-powered ferries facilitated the growth of inter-modal travel across the Lowcountry landscape. An antebellum passenger from Ladson or Monck’s Corner, for example, could catch the morning train to Charleston and saunter down King Street to purchase a bathing costume. Taking the omnibus to East Bay Street, they could ride the ferry to Sullivan’s Island and take a dip in the ocean. Returning by ferry to Charleston, our hypothetical traveler could enjoy a fancy dinner in the city before catching the evening train back to their home in the country. Using the same inter-modal services, urbanites could commute to jobsites outside the city limits, or indulge in weekend escapes to the scenic countryside. Lowcountry residents and visitors alike made millions of such journeys, without the use of automobiles, in the century following the advent of passenger rail service in 1832.

Also during the second quarter of the nineteenth century, the rise of omnibuses, streetcars, and steam-powered ferries facilitated the growth of inter-modal travel across the Lowcountry landscape. An antebellum passenger from Ladson or Monck’s Corner, for example, could catch the morning train to Charleston and saunter down King Street to purchase a bathing costume. Taking the omnibus to East Bay Street, they could ride the ferry to Sullivan’s Island and take a dip in the ocean. Returning by ferry to Charleston, our hypothetical traveler could enjoy a fancy dinner in the city before catching the evening train back to their home in the country. Using the same inter-modal services, urbanites could commute to jobsites outside the city limits, or indulge in weekend escapes to the scenic countryside. Lowcountry residents and visitors alike made millions of such journeys, without the use of automobiles, in the century following the advent of passenger rail service in 1832.

The facilities to welcome railroad passengers arriving at or departing from Charleston formed an important part of this transportation history. The South Carolina Rail Road (later called Southern Railway) opened a passenger station on Line Street in December 1830, then moved to Mary Street (from 26 January 1835), then to John Street (from 28 May 1850), then back to Line Street (from 20 February 1854). One year later, on the 7th of May 1855, the new North Eastern Rail Road Company (later part of the Atlantic Coast Line) opened a passenger station near the east end of Chapel Street, where the extension of East Bay Street now crosses. That depot was destroyed in February 1865, but it was rebuilt and continued to serve passengers until 1907. On the 10th of November that year, Charleston opened its first consolidated passenger depot, a grand, Italianate building called Union Station, at the northeast corner of East Bay and Columbus Streets.[2]

When Charleston’s Union Station finally opened in 1907, after several years of delays, most rail passengers arriving in the city either walked to their destination or stepped aboard one of the city’s electric trolleys. Gasoline-powered automobiles first appeared in Charleston in 1900, but that novel form of transportation served only a small minority of the population in the early years of the twentieth century. By the autumn of 1907, for example, there were just one hundred of the horseless carriages registered within the city (see Episode No. 114). Passenger rail travel continued to form the backbone of regional transportation across the Lowcountry into the 1920s, at which point the tide began to turn in favor of the four-wheeled machine.

When Charleston’s Union Station finally opened in 1907, after several years of delays, most rail passengers arriving in the city either walked to their destination or stepped aboard one of the city’s electric trolleys. Gasoline-powered automobiles first appeared in Charleston in 1900, but that novel form of transportation served only a small minority of the population in the early years of the twentieth century. By the autumn of 1907, for example, there were just one hundred of the horseless carriages registered within the city (see Episode No. 114). Passenger rail travel continued to form the backbone of regional transportation across the Lowcountry into the 1920s, at which point the tide began to turn in favor of the four-wheeled machine.

In the spring of 1925, ninety-three years after the debut of rail service between Charleston and Summerville, local residents and visitors enjoyed the convenience of twelve trains running daily between the two communities with multiple stops along the way. This venerable route, covering approximately twenty-two miles, was both the oldest and busiest mass-transit corridor in the state. Declining ridership was beginning to reduce corporate profits, however, so that summer the railroad company deleted two trains from the usual daily schedule. Angry citizens complained to the South Carolina Railroad Commission (formed in 1878), but the agency couldn’t force the service provider to operate at a loss. The public simply had to adjust their commuting habits and make the most of the remaining ten daily trains.[3]

Two years later, in the summer of 1927, Southern Railway announced the deletion of four daily commuter trains that stopped at multiple points between Summerville and Charleston. Six trains would continue to call at Flower Town and the Palmetto City each day, but they were all long-haul lines emanating from Columbia, August, and points beyond. To accommodate Lowcountry customers who wanted to stop at one of the traditional depots like Ladson, Woodstock, or the Navy Yard in North Charleston, the rail company partnered with a private company operating a handful of new diesel-powered buses. The Atlantic Coast Line made a similar change in the summer of 1929, by which time passenger rail service in and out of Charleston was just a fraction of its former bounty.[4]

The number and frequency of passenger trains traversing the Lowcountry to Charleston declined further during the Great Depression of the 1930s and during the wartime economy of the 1940s, while the number of local automobiles skyrocketed. By the time a fire destroyed Charleston’s Union Station on the morning January 10th, 1947, there was little momentum to build a replacement. Diesel buses had replaced the city’s urban trolley system in February 1938, and the dwindling number of rail commuters arriving at or departing from Charleston did not warrant the expense of a new facility. Instead, Southern Railway parked an old passenger car on its Line Street property and used it as a makeshift passenger depot for nearly a decade.[5]

The number and frequency of passenger trains traversing the Lowcountry to Charleston declined further during the Great Depression of the 1930s and during the wartime economy of the 1940s, while the number of local automobiles skyrocketed. By the time a fire destroyed Charleston’s Union Station on the morning January 10th, 1947, there was little momentum to build a replacement. Diesel buses had replaced the city’s urban trolley system in February 1938, and the dwindling number of rail commuters arriving at or departing from Charleston did not warrant the expense of a new facility. Instead, Southern Railway parked an old passenger car on its Line Street property and used it as a makeshift passenger depot for nearly a decade.[5]

The historic rail line from Branchville to Hamburg, a world-record achievement in 1833, carried its last passengers in September 1950. The Seaboard Line ran its last passenger train from Savannah to Charleston two years later, in December 1952. To replace the lost Union Station, Southern Railway opened a much smaller passenger terminal in March of 1956 at a place then called Seven Mile, now on the edge of Park Circle in North Charleston. Travelers wishing to catch the one and only passenger train connecting Charleston to Summerville—the Carolina Special that continued on to Columbia—were obliged to take a bus between the city and the suburban train station. Finally, on the 26th of October, 1962, the Carolina Special ceased to carry passengers between Charleston and Columbia. For the first time since July 1832, there was no commuter rail service connecting the Lowcountry’s urban center with the smaller communities scattered across the tri-county area. That change in 1962 truly marked the end of a remarkable era in the long history of local transportation.[6]

The diesel buses that replaced Charleston’s electric trolleys in 1938 were owned and operated by a private firm, the South Carolina Power Company. That entity became the South Carolina Electric and Gas Company in 1948, and continued to operate urban bus routes for a further fifty years. SCE&G’s decision to terminate that valuable service sparked the 1997 creation of CARTA—the Charleston Area Regional Transportation Authority. Today CARTA continues the work pioneered by Charleston’s earliest horse-drawn omnibuses in 1833, but it was never intended to replace the passenger rail that once provided rapid transit up and down the region’s principal transportation corridor.

The passenger rail service that commenced between Charleston and Summerville in 1832 energized local commerce and culture for more than a century. The decision to abandon that important link in the region’s inter-modal transportation network in the mid-twentieth century was driven by a widespread preference for the new-fangled independence of the automobile and the plentiful supply of cheap gasoline. Over the past several decades, the perils of automotive gridlock and our unsustainable reliance on fossil fuels have convinced many people in this community and beyond to look for viable alternatives. Since the early 1990s, some local transportation advocates have suggested that we rebuild the former passenger rail service, or invest in the kind of inter-urban light rail system that you might find in the larger cities of the Northeast and in Europe. Proposals to reactivate the old rails or to lay new ones are now prohibitively expensive and geographically impractical, however. Fortunately, there is a compromise solution at hand that merits serious attention.

The passenger rail service that commenced between Charleston and Summerville in 1832 energized local commerce and culture for more than a century. The decision to abandon that important link in the region’s inter-modal transportation network in the mid-twentieth century was driven by a widespread preference for the new-fangled independence of the automobile and the plentiful supply of cheap gasoline. Over the past several decades, the perils of automotive gridlock and our unsustainable reliance on fossil fuels have convinced many people in this community and beyond to look for viable alternatives. Since the early 1990s, some local transportation advocates have suggested that we rebuild the former passenger rail service, or invest in the kind of inter-urban light rail system that you might find in the larger cities of the Northeast and in Europe. Proposals to reactivate the old rails or to lay new ones are now prohibitively expensive and geographically impractical, however. Fortunately, there is a compromise solution at hand that merits serious attention.

In recent years, transportation advocates in Berkeley, Charleston, and Dorchester Counties have been studying and planning an alternative to light rail that is gaining traction in diverse communities around the world. The concept is essentially a hybrid of old ideas, existing infrastructure, and new technology. Bus Rapid Transit, or BRT, uses low-emission or electric buses to carry passengers along a dedicated route, using the existing paved roads, with the same convenience and speed once provided by suburban and inter-urban trains. The Berkeley-Charleston-Dorchester Council of Governments (BCDCOG) has been planning a BRT system for this community for several years, and their preliminary work will soon become a reality. Through their perseverance, the long-lost tradition of rapid transit between Charleston and Summerville, with several intermediary stops, will once again energize the local scene.

If you’re unfamiliar with the concept of Bus Rapid Transit, or haven’t yet heard about the local plans for a BRT route, the BCDCOG has assembled a significant amount of information on their website that I encourage everyone to review (at lowcountryrapidtransit.com). At this moment (May 2021), the agency has a new virtual presentation online that you can view at your leisure and submit feedback and comments if you like. If you miss this window of opportunity to participate in the conversation, you’ll be hearing more about BRT in the coming years and have other chances to get involved.

As a citizen who would rather share a ride than drive when I have to travel, I’m personally excited by the prospect of Bus Rapid Transit on the local horizon. As a historian focused on the cultural evolution of this area, I see BRT as both the rebirth of a venerable tradition and the harbinger of a new era of transportation. The creation of a mass transit link between Summerville and Charleston in 1832 nurtured the growth of numerous suburban neighborhoods between the two points. After years of automotive gridlock on our highways, BRT could ease the congestion and revive that long-lost transportation convenience. Once again, a reflection on our community’s shared past provides useful inspiration for our future.

[1] For information on the early years of the SCCRRC, see Ulrich Bonnell Phillips, A History of Transportation in the Eastern Cotton Belt to 1860 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1908), 136–67; [Charleston, S.C.] Southern Patriot, 16 April 1832, page 3, “Rail Road Pleasure Trips”; Charleston Courier, 2 July 1832, page 3, “Rail Road Conveyance to New Summerville.”

[2] Courier, 24 December 1830, page 2; Courier, 23 January 1835, page 2, “Notice to Rail Road Passengers”; Courier, 28 May 1850, page 3, “So. Ca. Rail Road Company”; Courier, 17 February 1854, page 3, “So. Ca. Rail Road Company”; Courier, 2 May 1855, page 3, “North-Eastern Rail Road”; Charleston Sunday News, 10 November 1907, page 6, “Charleston’s New Union Passenger Station.”

[3] Charleston News and Courier, 4 August 1925, page 8, “Train Schedules to be Discussed.”

[4] News and Courier, 5 June 1927, page 14: “Cut off Trains to Summerville”; News and Courier, 3 August 1929, page 4: “On the Branch Lines”; News and Courier, 9 November 1930, page 2, letter from “Commuter.”

[5] Evening Post, 10 January 1947, page 1.

[6] News and Courier, 24 September 1950, page 6C, “History Made when Last Southern Passenger Train Rolled on Branchville-Augusta Tracks”; Evening Post, 31 December 1952, page 2, “Seaboard Train Makes Final Run”; News and Courier, 15 March 1956, page 16A, “New Southern Terminal Gets 1st Use Today”; News and Courier, 9 August 1962, page 1, “Southern To Stop Run of Special”; Evening Post, 31 August 1962, page 1, “The ‘Carolina Special’ It Keeps On Rolling Along”; News and Courier, 26 September 1962, page 14, “Hearings Concluded on Carolina Special”; News and Courier, 27 September 1962, page 1, “Last run set for Oct. 26 for Carolina Special.”

NEXT: Parishes, Districts, and Counties in Early South Carolina

PREVIOUSLY: The Forgotten Dead: Charleston’s Public Cemeteries, 1794–2021

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments