The Rise of Charleston’s Horn Work, Part 1

Processing Request

Processing Request

The tabby Horn Work that once guarded the northern approach to Charleston formed the citadel of American resistance during the British siege of 1780, but the story of its construction commenced decades before the Revolution. It arose from prolonged conversations about the best manner of defending the backside of South Carolina’s colonial capital, and was intended to supersede earlier, less remarkable works. Prompted by the outbreak of a new war with France in 1756, local officials and royal engineers bit the bullet and ordered the construction of several new fortifications that would transform the Lowcountry landscape.

Last week I provided an overview of a neglected fortification called the Horn Work that once straddled King Street along the northern edge of colonial Charleston. Having already described the highlights of that structure’s general design, materials, and dimensions, I’d like to segue into a more detailed investigation of its construction in the late 1750s. That era marked the final phase of a long series of fortification projects in urban Charleston that stretched back to the 1670s. Time doesn’t permit a full recital of the several construction campaigns leading up to the 1750s, but a brief synopsis of some of that material will help set the stage, so to speak, for the rise of the Horn Work and help us appreciate its role in our community’s long history.

Defending the Northern Approach to Charleston:

Charleston’s original northern boundary was a line stretching from the Ashley River to the Cooper River along what is now Beaufain Street (continuing a bit south of Hasell Street), but the heart of the early settlement was further to the south and east. The town’s earliest, seventeenth-century fortifications concentrated on defending the Cooper River waterfront, but in 1703 the provincial legislature adopted a plan to surround the town’s highest land with a system of entrenchments—earthen walls and bastions surrounded by a broad ditch. That plan included a triangular ravelin or fortified island at the intersection of Meeting and Broad Streets, which provided a western gateway to the Broad Path (King Street) leading in and out of the town. It was inevitable that the town would eventually outgrow these works, however, and the entrenchments and ravelin were removed sometime in the early 1730s (the exact date is now lost).

Charleston’s original northern boundary was a line stretching from the Ashley River to the Cooper River along what is now Beaufain Street (continuing a bit south of Hasell Street), but the heart of the early settlement was further to the south and east. The town’s earliest, seventeenth-century fortifications concentrated on defending the Cooper River waterfront, but in 1703 the provincial legislature adopted a plan to surround the town’s highest land with a system of entrenchments—earthen walls and bastions surrounded by a broad ditch. That plan included a triangular ravelin or fortified island at the intersection of Meeting and Broad Streets, which provided a western gateway to the Broad Path (King Street) leading in and out of the town. It was inevitable that the town would eventually outgrow these works, however, and the entrenchments and ravelin were removed sometime in the early 1730s (the exact date is now lost).

As early as September 1738, ahead of a new war with Spain, the provincial government of South Carolina considered cutting a line of entrenchments across the peninsula in the approximate location of present-day Calhoun Street, but nothing was done at that time. In 1744, while Britain waged war against both Spain and France, the provincial legislature revised its thinking and considered digging a new line of entrenchments across the peninsula in the approximate location of present-day Market Street.[1] Visiting engineer Peter Henry Bruce encouraged these plans in early 1745 by proposing to construct a large fortified “citadel” at what is now the intersection of King and Market Streets to defend the northern approaches to the town. The provincial government deemed Bruce’s plan too large and too expensive, so local merchant and amateur engineer Othniel Beale reduced it to a much simpler and cheaper line of earthen entrenchments and bastions. Beale’s plan was approved by the legislature in May 1745 and immediately set in motion.[2] The town’s second gate and drawbridge, standing at what is now the intersection of King and Market Streets, were dismantled during a period of peace in 1750, but the line of entrenchments and moat along what its now Market Street stood until 1766.[3]

The construction of new fortifications was a low priority in South Carolina during the peaceful years of the early 1750s. The provincial legislature approved funding in 1752 for the construction of a new Anglican church for the urban parish of St. Michael, and the following year finally set in motion the construction of a proper State House. During that same era, however, Governor James Glen personally invited a visiting engineer, William De Brahm, to draft a plan for new fortifications around Charleston. Hoping to impress the colonial government, De Brahm proposed an elaborate system of robust fortifications around the peninsular town, including a massive, diamond-shaped “citadel,” similar to that proposed by Bruce in 1745, at a site now occupied by the intersection of King and Calhoun Streets.[4] Even after the capital’s fortifications were largely wrecked by the hurricane of September 1752, the legislature refused to consider De Brahm’s defensive plan during a time of general peace in Europe and the colonies.

The South Carolina legislature ignored De Brahms’s proposals until the spring of 1755, when increasing political tensions between Britain and France presaged the outbreak of a new war. Suddenly under pressure from the provincial government to reduce the scope of his 1752 plan, De Brahm produced a revised version proposing a simpler fortified line along Charleston’s northern boundary, complete with several cannon batteries and a detached ravelin—a sort of fortified triangular island—adjacent to what is now the intersection of King and Hasell Streets.[5] The local Commissioners of Fortifications, a board of gentlemen appointed by the governor, reviewed De Brahm’s revised plan in July 1755 and dismissed the idea of funding any new works along the town’s northern line. In their opinion, the line of entrenchments constructed in 1745 along what is now Market Street were adequate for defending the northern approach to Charleston.[6]

The South Carolina legislature ignored De Brahms’s proposals until the spring of 1755, when increasing political tensions between Britain and France presaged the outbreak of a new war. Suddenly under pressure from the provincial government to reduce the scope of his 1752 plan, De Brahm produced a revised version proposing a simpler fortified line along Charleston’s northern boundary, complete with several cannon batteries and a detached ravelin—a sort of fortified triangular island—adjacent to what is now the intersection of King and Hasell Streets.[5] The local Commissioners of Fortifications, a board of gentlemen appointed by the governor, reviewed De Brahm’s revised plan in July 1755 and dismissed the idea of funding any new works along the town’s northern line. In their opinion, the line of entrenchments constructed in 1745 along what is now Market Street were adequate for defending the northern approach to Charleston.[6]

Believing that potential invaders might sail into Charleston harbor and attack first the southern tip of the peninsula, the Commissioners of Fortifications instructed William De Braham to commence construction of his new defensive works at White Point. Preliminary work commenced at that site in the summer of 1755 with the foundations of a new gun battery—later called Lyttelton Bastion—located midway between Granville Bastion (built ca. 1697–1700) and Broughton’s Battery (built 1736–38). After nearly nine months of slow progress, the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly resolved in late March 1756 to limit the scope of Mr. De Brahm’s construction to the works then underway at White Point. A feeling of mutual frustration induced Mr. De Brahm to retreat to the backcountry that summer to oversee the construction of Fort Loudoun in the Overhill Cherokee territory of what is now eastern Tennessee. As Lieutenant Governor William Bull later remarked in 1770, Mr. De Brahm “and his plan were laid aside.”[7]

A New War With France:

William Henry Lyttelton (1724–1808) arrived in Charleston in June 1756 and immediately took office as South Carolina’s new royal governor. Two months later, news arrived from London that King George II had declared war on France on May 17th.[8] That autumn, the provincial legislature began to consider methods of putting the colony in a better “posture of defense” by strengthening its fortifications and expanding the militia. At the same time, Governor Lyttelton wrote to the Earl of Loudoun, the commander-in-chief of British forces in North America, and asked him to send regular troops and an engineer to help defend South Carolina. While the provincial government waited for professional assistance to arrive from afar, local authorities did their best to prepare for war.

In late January 1757, the South Carolina legislature resolved to build a new magazine in the village of Dorchester to house a reserve supply of gunpowder in case enemy forces captured Charleston. In mid-February, the Commissioners of Fortifications conducted a “trial” at Fort Johnson on James Island to see if tabby, a popular local form of concrete composed largely of oyster shells, might make an acceptable substitute for brick work. Local bricklayer and tabby expert Thomas Gordon convinced the commissioners that tabby was more permanent than earthen fortifications and cheaper than brickwork, and won the contract to fortify the magazine at Dorchester.[9] In early March, the provincial legislature resolved to spend large sums of public money to repair and strengthen Fort Johnson and to construct a new fort on Port Royal Island near the town of Beaufort.[10] Meanwhile, South Carolina’s only resident professional engineer, William De Brahm, recently returned from Cherokee territory, felt slighted by the government’s abridgement of his fortification plans and departed for Georgia in a huff.[11] The local legislature was proposing to throw large sums of money at various fortification projects during a time of perceived danger, but, for the moment, the province lacked a skilled professional to oversee their design.

In late January 1757, the South Carolina legislature resolved to build a new magazine in the village of Dorchester to house a reserve supply of gunpowder in case enemy forces captured Charleston. In mid-February, the Commissioners of Fortifications conducted a “trial” at Fort Johnson on James Island to see if tabby, a popular local form of concrete composed largely of oyster shells, might make an acceptable substitute for brick work. Local bricklayer and tabby expert Thomas Gordon convinced the commissioners that tabby was more permanent than earthen fortifications and cheaper than brickwork, and won the contract to fortify the magazine at Dorchester.[9] In early March, the provincial legislature resolved to spend large sums of public money to repair and strengthen Fort Johnson and to construct a new fort on Port Royal Island near the town of Beaufort.[10] Meanwhile, South Carolina’s only resident professional engineer, William De Brahm, recently returned from Cherokee territory, felt slighted by the government’s abridgement of his fortification plans and departed for Georgia in a huff.[11] The local legislature was proposing to throw large sums of money at various fortification projects during a time of perceived danger, but, for the moment, the province lacked a skilled professional to oversee their design.

In mid-June 1757, a detachment of five companies of the first battalion of His Majesty’s 60th Regiment of Foot, the so-called “Royal Americans,” arrived from New York. Their commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Bouquet, a native of Switzerland, was himself something of an amateur engineer, but he brought with him a more capable fortification expert.[12] Among the multi-lingual officers that Lt. Col. Bouquet had recruited in Switzerland in early 1756 was one Emanuel Hess, a young engineer who accepted a lieutenant’s commission that February.[13] During his nine-months residency in South Carolina, from mid-June 1757 to late March 1758, Lieutenant Hess visited a number of fortified sites in the colony, conversed with public officials, and learned about the virtues of oyster-shell tabby concrete from local tradesmen. All of the fortified works he designed during this short period, including an expansion of Fort Johnson on James Island, modifications to De Braham’s fortifications at White Point, a new fort on Port Royal Island, and the Horn Work in Charleston, made use of tabby construction. Hess’s tenure in the Lowcountry might have been brief, but his talent for military architecture left an enduring stamp on the local landscape.

Alarmed by the state of war with the powerful French military, a number of inhabitants petitioned the provincial government in late June 1757 for increased fortifications around Charleston. They worried that “the naked and defenseless situation of this town & harbor” might tempt France “to make a vigorous push” to attack Charleston. The petitioners begged the legislature “to exercise every stratagem that can be invented to make the place as defensible as the time will admit of. They shall most chearfully [sic] pay their proportions of the expence be it what it will, being convinced that if the enemy shou’d once become masters of this town the whole country will irrecoverably be lost.” Having heard of the arrival of Lieutenant Hess, the inhabitants asked the assembly to undertake “the most active vigorous measures possible . . . that the engineer Lord Loudoun has been so kind to send here may be enabled to do the best he can with all dispatch.”[14]

On June 28th, Gov. Lyttleton informed the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly that he had earlier written to the Earl of Loudoun asking him to send an engineer to improve “the weak & defenceless [sic] condition of the fortifications” in the province. “I have now the pleasure to acquaint you,” said the governor, “that his Lordship has sent Captn. Hesse [sic], a good & able engineer. And Lieutenant-Colonel Bouquet, who commands the forces, is also very well vers’d in that art. These gentlemen are of opinion that new works are necessary to be constructed, without delay, as well here [in Charleston], as at Fort-Johnson, to prevent this place from falling an easy prey to the enemy, in case of an attack: But if you will grant a free & liberal aid, this town & province may, in a few months, be put in such a state of defence as not to dread one.”[15]

On June 28th, Gov. Lyttleton informed the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly that he had earlier written to the Earl of Loudoun asking him to send an engineer to improve “the weak & defenceless [sic] condition of the fortifications” in the province. “I have now the pleasure to acquaint you,” said the governor, “that his Lordship has sent Captn. Hesse [sic], a good & able engineer. And Lieutenant-Colonel Bouquet, who commands the forces, is also very well vers’d in that art. These gentlemen are of opinion that new works are necessary to be constructed, without delay, as well here [in Charleston], as at Fort-Johnson, to prevent this place from falling an easy prey to the enemy, in case of an attack: But if you will grant a free & liberal aid, this town & province may, in a few months, be put in such a state of defence as not to dread one.”[15]

Shortly after the arrival of the 60th Regiment, Lt. Col. Henry Bouquet convinced the provincial government that it was necessary to construct additional barracks for the British troops to be quartered in Charleston during the war.[16] Echoing the earlier advice of Peter Henry Bruce and William De Brahm, he also convinced them to build a new fortification to protect the northern approach to Charleston. Bouquet noted in a letter to Lord Loudoun that the town had “some old fortifications towards the sea, but the back part [that is, to the north of the town,] is quite open, and in supposing that the Assembly wou’d grant the necessary sums to fortify the land side, it will still prove a difficult task, by the great number of houses scatter’d all around.”[17]

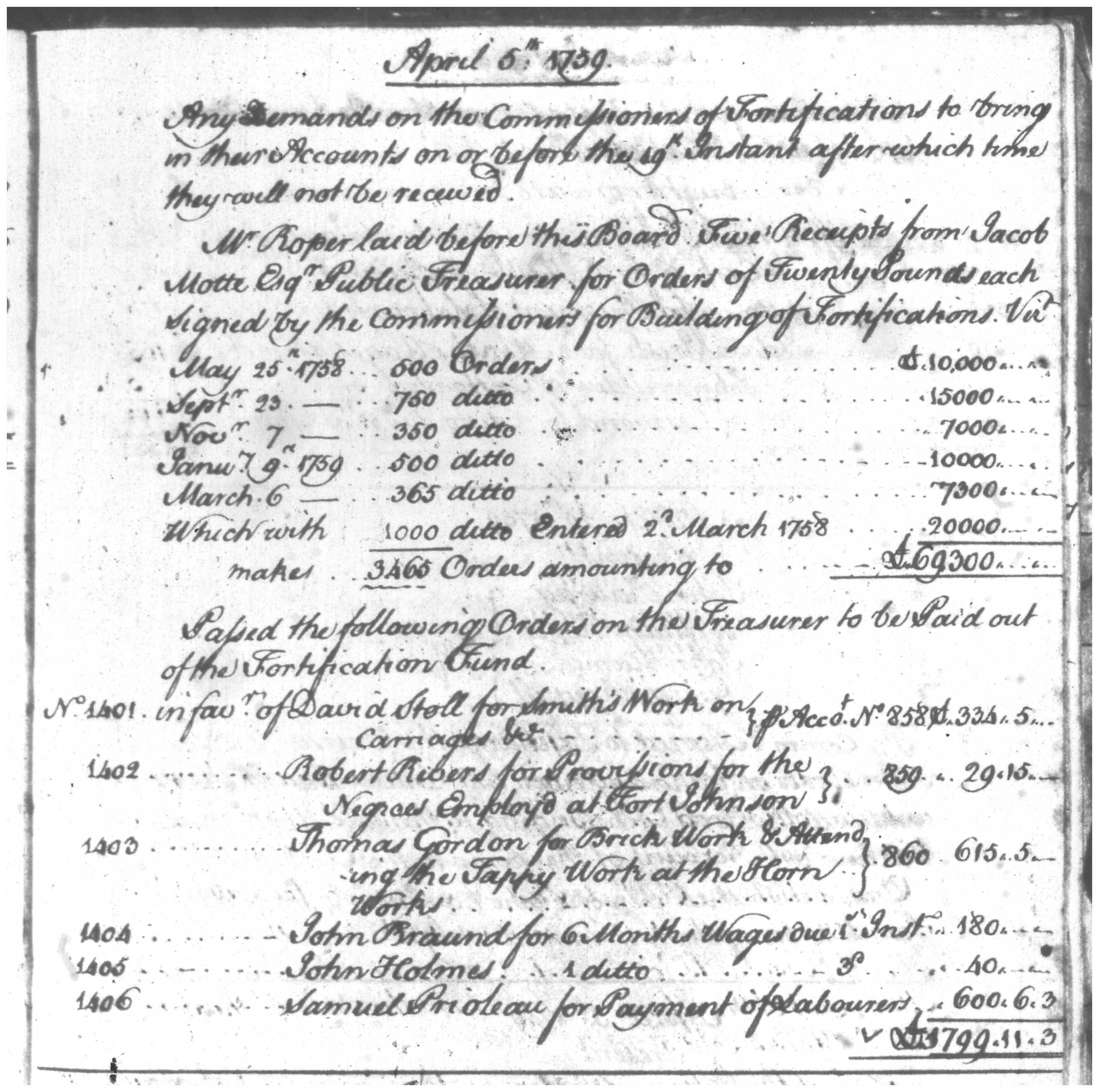

After agreeing to build new barracks and a new fortification on the “back part” of Charleston, which became the Horn Work, the provincial government of South Carolina was now committed to funding six different military construction projects across the Lowcountry landscape in addition to the ongoing efforts to build St. Michael’s Church and the State House. To fund the new defensive works, the legislature ratified an act on July 6th, 1757, to appropriate £44,000 of the provincial tax revenues during the coming year towards the construction fortifications in urban Charleston and at Fort Johnson. The paper trail of accounts related to these projects is now incomplete and confusing, but it provides important clues that help us understand the rise of the Horn Work and other contemporary structures.[18]

Planning Fort Lyttelton:

In mid-August 1757, Governor William Henry Lyttelton accompanied Henry Bouquet and Emanuel Hess on a week-long excursion to Beaufort to view the site of the proposed new fort on Port Royal Island.[19] Shortly after their return to Charleston, on August 25th, “Mr. Hesse the engineer” presented to the Commissioners of Fortifications “a plan of a fort to be built on Spanish Point on Port Royal River.” A copy of that plan was later sent to the Earl of Loudoun, and it now survives in the collections of the Huntington Library in California.[20] Hess’s hand-colored illustration of what became known as Fort Lyttelton forms the perfect companion to a robust description of the fort’s design and construction found in the contemporary manuscript journal of the Commissioners of Fortifications.

Because Port Royal Island was fifty miles southwest of Charleston (as the crow flies), the governor deputized several local gentlemen to oversee that construction project. He also required those deputies to send periodic reports to the Commissioners of Fortifications in Charleston summarizing the details of contracts, laborers, materials, “and the progress of the work from time to time.” Thanks to their dutiful compliance with the governor’s instructions, the lone surviving journal of the Commissioners of Fortifications includes a pretty remarkable record of the construction of Fort Lyttelton between late 1757 and early 1759.[21]

Because Port Royal Island was fifty miles southwest of Charleston (as the crow flies), the governor deputized several local gentlemen to oversee that construction project. He also required those deputies to send periodic reports to the Commissioners of Fortifications in Charleston summarizing the details of contracts, laborers, materials, “and the progress of the work from time to time.” Thanks to their dutiful compliance with the governor’s instructions, the lone surviving journal of the Commissioners of Fortifications includes a pretty remarkable record of the construction of Fort Lyttelton between late 1757 and early 1759.[21]

We know, for example, that the walls of Fort Lyttelton encompassed “40,000 [cubic] feet of solid tappy [tabby] work” and “65,000 cubical feet of earth for [filling] the parapet & banquette.” We know that construction commenced in late October 1757 with around fifty enslaved men, plus the “tappy maker” and several white overseers. Within the first six weeks of work, locals had delivered approximately thirty thousand bushels of oyster shells, and boats continued to bring more to the site daily. At the end of fourteen weeks, approximately seventy thousand bushels of oyster shells had been delivered. Nearly one year after commencing construction, the commissioners were contemplating the best manner of finishing the merlons or uppermost parts of the walls of Fort Lyttelton.[22]

In contrast to the bounty of information documenting the rise of Fort Lyttelton, the surviving records of the construction of the Horn Work in urban Charleston are far less complete. Hess’s original plan, drawn at the same time as that of Fort Lyttelton, has not been found. The board of Commissioners of Fortifications appointed three of its own members, Thomas Smith, Daniel Crawford, and John Hume, to superintend the construction of the Horn Work, and those men apparently reported its progress verbally to their colleagues. If the commissioners and the governor wished to satisfy their curiosity about the progress of the Horn Work, they simply rode up King Street to view the site with their own eyes. Because there was no need to send periodic written reports about its progress to distant commissioners, most of the details of its construction were never recorded.

The financial records of the Commissioners of Fortifications provide additional valuable details about the various government-funded construction projects of the late 1750s. Expenses related to four of the six fortification projects undertaken in South Carolina during the period 1757–59 were paid from discrete streams of revenue appropriated by specific acts of the legislature. Accounts related to the work on James Island, for example, were “paid out of the money granted for repairing and strengthening Fort Johnson,” while those related to Fort Lyttelton on Port Royal Island, the magazine at Dorchester, and the barracks in Charleston were paid from similarly separate funds. Because the clerk of the Commissioners of Fortifications, Samuel Prioleau, always separated the accounts related to those four projects, the board’s surviving financial records provide a relatively clear picture of the contractors, overseers, materials, and the total expenses related to each respective project.

In contrast to this accounting transparency, however, the two distinct fortification projects progressing in urban Charleston during that same period are not as easily distinguished. In the surviving manuscript journal, the clerk of the Commissioners of Fortifications combined accounts related to Mr. De Brahm’s works on the southern tip of the peninsula and accounts related to Mr. Hess’s Horn Work on the north side of the town into a single column of expenses “to be paid out of the Fortification Fund.” This arrangement renders it very difficult to determine which individuals, materials, and expenses are related to one or the other of the two projects. The clerk tagged a few of these accounts with specific geographic language, such as “on the North Works” or “on White Point,” but the majority cannot now be tied to one or the other of the two urban projects with certainty.

Planning the Horn Work:

On the same day that Emanuel Hess submitted his plan for Fort Lyttelton to the local government (25 August 1757), Lt. Col. Bouquet wrote to the Earl of Loudoun to summarize their defensive strategy for the capital of South Carolina. The Swiss officer noted that “some out works will be raised on the land side [to the north]; the marshes which surround the town that way, make its situation naturally strong.”[23] Lieutenant Hess apparently made at least one duplicate of his design for the Horn Work, which Henry Bouquet forwarded to the Earl of Loudoun in mid-October. Because Hess’s illustration is now lost, Bouquet’s narration of the Charleston landscape merits a full reading:

On the same day that Emanuel Hess submitted his plan for Fort Lyttelton to the local government (25 August 1757), Lt. Col. Bouquet wrote to the Earl of Loudoun to summarize their defensive strategy for the capital of South Carolina. The Swiss officer noted that “some out works will be raised on the land side [to the north]; the marshes which surround the town that way, make its situation naturally strong.”[23] Lieutenant Hess apparently made at least one duplicate of his design for the Horn Work, which Henry Bouquet forwarded to the Earl of Loudoun in mid-October. Because Hess’s illustration is now lost, Bouquet’s narration of the Charleston landscape merits a full reading:

I lay before your Lo[rdshi]p the plan of this town & harbour, with the fortifications that I have directed Lieut. Hess to draw.

We have endeavour’d to dispose the works in the best manner so as to require a small number of men for their defence.

The marshes are impracticable [that is, impassable] near the rivers, the part on the left defended by one redoubt and two towers; the right by two redoubts, and the only weak part of the neck will be sufficiently covered by the horn work, supported by the four redoubts; and the intrenchment beyond. It was necessary to carry out the works at that distance [from the town], by the following considerations—

1st. To take the advantage of that situation, which can be compleately [sic] fortify’d with few works.

2d. To leave a proper place for new buildings, as the town is daily increasing.

3. To reduce [induce?] the enemy to make his attacks at such a distance, that the town might suffer little by a siege.

4. To have room for another inclosure [sic] made of part of the old decayed rampart [built in 1745], & the new intrenchmt [entrenchment] pointed in the draught.

This plan has been approved of here by the Govr. and the Commissioners of Fortifications, and shall immediately be put in execution. . . . I am very far to think myself a competent judge of fortifications, but I have done nothing without mature reflection. My design has been to make the best of the situation, and with a few works and a moderate expence make this town sufficiently strong to be easily defended with a small garrison.

Your Lordship is the proper judge how far this plan may answer the end proposed.[24]

After a busy summer of planning and negotiating, the Commissioners of Fortifications finally turned their attention to the new works to defend Charleston’s northern boundary in October 1757. With five other fortification projects underway, in addition to the unfinished St. Michael’s Church and State House, the provincial government was spending a lot of money to hire dozens of white contractors and hundreds of enslaved laborers across the Lowcountry. To supplement the labor force with minimal expense to the provincial government, Lt. Col. Bouquet and Lt. Col. Archibald Montgomery of the newly-arrived 62nd Regiment of Foot (later renamed the 77th Regiment of Highlanders), offered their men for extra duty. On October 10th, they agreed with Governor Lyttelton to employ soldiers in the construction of the new works at the daily rate of three shillings and six pence currency (six pence sterling) each, plus one gill of rum (a quarter of a pint), for six hours of work (half a work day). At a meeting that afternoon held at the Council Chamber, Governor Lyttelton informed the Commissioners of Fortifications of this labor deal and then “delivered to them the plan of the works to be carried on across the Town Neck and recommended to them to carry the same into execution with all convenient speed.”[25]

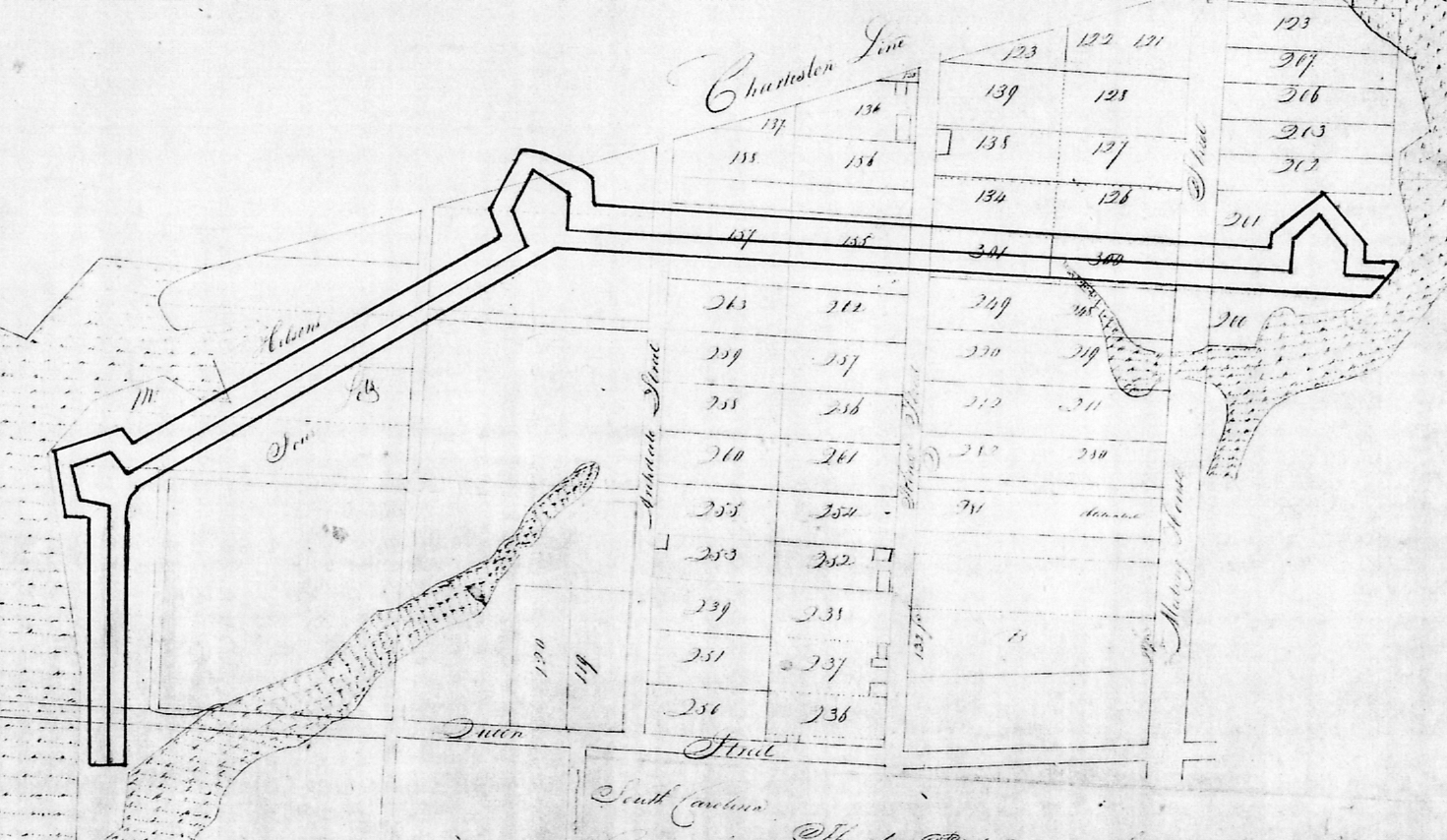

With a plan in hand and workmen at the ready, there was just one minor detail delaying the commencement of the Horn Work: the government had not yet acquired the legal rights to the necessary land. In past projects, South Carolina’s provincial government had simply exercised its right of eminent domain and usurped whatever property was deemed necessary for the defensive purposes. In the late 1750s, however, the local government attempted to negotiate with land owners in advance when possible. Working with their military advisors in the autumn of 1757, the Commissioners of Fortifications selected a site for the Horn Work nearly seven hundred yards or approximately six hundred meters north of the town boundary (now Beaufain Street). The property in question encompassed a pair of bucolic pastures owned by Peter Manigault, on the west of the Broad Path, and John Wragg to the east of the road. Walking over the land with both of the owners on October 28th, the commissioners marked the boundaries of their proposed acquisition and directed Lieutenant Hess to survey the land necessary for his plans. The engineer reported on November 8th that the area in question contained “about fourteen acres,” though it was later more precisely described 6.25 acres on the west side of the Broad Path and 8.75 acres on the east (now Marion Square). Messrs. Manigault and Wragg apparently agreed in principal to the sale in at that time, but they did not convey titles to the land until the following July.[26]

With a plan in hand and workmen at the ready, there was just one minor detail delaying the commencement of the Horn Work: the government had not yet acquired the legal rights to the necessary land. In past projects, South Carolina’s provincial government had simply exercised its right of eminent domain and usurped whatever property was deemed necessary for the defensive purposes. In the late 1750s, however, the local government attempted to negotiate with land owners in advance when possible. Working with their military advisors in the autumn of 1757, the Commissioners of Fortifications selected a site for the Horn Work nearly seven hundred yards or approximately six hundred meters north of the town boundary (now Beaufain Street). The property in question encompassed a pair of bucolic pastures owned by Peter Manigault, on the west of the Broad Path, and John Wragg to the east of the road. Walking over the land with both of the owners on October 28th, the commissioners marked the boundaries of their proposed acquisition and directed Lieutenant Hess to survey the land necessary for his plans. The engineer reported on November 8th that the area in question contained “about fourteen acres,” though it was later more precisely described 6.25 acres on the west side of the Broad Path and 8.75 acres on the east (now Marion Square). Messrs. Manigault and Wragg apparently agreed in principal to the sale in at that time, but they did not convey titles to the land until the following July.[26]

Meanwhile, back in early November 1757, the Commissioners of Fortifications agreed that three of their board members, Thomas Smith, Daniel Crawford, and John Hume, would jointly oversee the construction of the Horn Work and “superintend the works to be carried on across the town neck thro’ Mr. John Wragg’s & Mr. Peter Manigault’s Land.” Lt. Col. Bouquet then informed the commissioners that his soldiers were ready to begin work as soon as tools were available. The board agreed to employ one hundred soldiers beginning on Monday, November 14th, and instructed the superintendents of the Horn Work “to give directions for a sufficient number of wheel barrows & spades to be sent to the place where the people are to go to work.”[27]

I’m out of time for this week, so we’ll pause the story of the Horn Work here for the moment. Next week, we’ll follow the story of the tradesmen, soldiers, enslaved laborers, and boatmen who transformed tons of oyster shells into a towering white gate that—before it defended American soldiers—succeeded in causing traffic jams on King Street for many years.

[1] Act No. 652, “An Act for the further Security and better Defence of this Province,” ratified on 18 September 1738, in Acts Passed by the General Assembly of South-Carolina, At a Sessions begun and holden at Charles-Town, on Tuesday the Tenth of November in the Year of our Lord, One Thousand, Seven Hundred and Thirty-six, and in the Tenth Year of the Reign of our Sovereign Lord George II, by the Grace of God of Great-Britain, France & Ireland King, Defender of the Faith, &c. And from thence continued by divers [sic] Prorogations and Adjournments to the Twenty-fifth Day of March, Anno Domini, 1738 (Charleston: Lewis Timothy, 1738 [1739]), 105–11; J. H. Easterby, ed., The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, February 20, 1744–May 25, 1745 (Columbia: State Commercial Printing Company for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1951), 215–26 (29 June 1744).

[2] See South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Journal of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, No. 14, pp. 127–28, 138; Peter Henry Bruce, Memoirs of Peter Henry Bruce, Esq. (London: Mrs. Bruce, 1782), 434–39; Act No. 729, “An Act for imposing an additional duty of six pence per gallon on Rum imported, and for granting the same to his Majesty, for the use of the Fortifications in this Province, and for allowing a discount of ten per centum out of the dutys on Sugars imported for wastage, and to direct the manner of making entrys [sic] of goods or merchandise imported, which are liable to pay more than one duty with the Country Comptroller and Public Treasurer, and for repealing an Act of the General Assembly of this Province, intitled [sic] ‘An Act for continuing a Duty and Imposition of three pence per gallon on Rum imported, and for raising a fund to finish and keep in repair the new brick Church in Charlestown, and for the more effectual carrying on and maintaining the Fortifications of this Province,[’] and for enlarging the number of the Commissioners of the Fortifications, and to impower [sic] the Commissioners of the Fortifications to stamp orders for defraying the expence of the works by this Act directed to be immediately carried on for the defence of Charlestown,” ratified on 25 May 1745, in Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 3 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnson, 1838), 653–56.

[3] R. Nicholas Olsberg, ed., The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, 23 April 1750–31 August 1751 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press for the South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1974), 105 (15 May 1750); SCDAH, Journal of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, No. 32, page 767 (30 May 1766).

[4] De Brahm delivered his “Plan of a Project to Fortifie [sic] Charles Town Done by Desire of his Excellency the Gouvernour [sic] in Council by William De Brahm Captain Ingeneer [sic] in the Service of his Late Imp: Maj: Charle [sic] VII” to Governor Glen on 24 November 1752; see SCDAH, Journal of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, No. 21, part 1, page 19. After sharing it briefly with the Commons House of Assembly, Glen sent the plan to England, and it is now found at the National Archive of the United Kingdom, CO 700/Carolina14.

[5] De Brahm’s 1755 revised “Plan of the City and Fortification of Charlestown” survives at the British Library, King’s MS.210.4, and is reproduced in Louis De Vorsey Jr., ed., De Brahm’s Report of the General Survey in the Southern District of North America (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1971), facing page 98. Note that De Brahm also proposed to cut a trench across the peninsula (approximately six miles north of Beaufain Street) that would have turned Charleston into an island town.

[6] The report of the Commissioners of Fortifications, dated 18 July 1755, appears in the Journal of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, 1755, at the National Archives of the United Kingdom, CO 5/471, pages 239–42 (21 July 1755). A photostatic copy of this journal is available at SCDAH, Journal of His Majesty’s Council for South Carolina, BPRO photostats No. 6.

[7] Terry W. Lipscomb, ed., The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, November 20, 1755–July 6 1757 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press for the South Carolina Department of Archives and History), 176 (30 March 1756); H. Roy Merrens, ed., The Colonial South Carolina Scene: Contemporary Views, 1697–1774 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1977), 261–62.

[8] South Carolina Gazette, 26 August—2 September 1756.

[9] SCDAH, Journal of the Commissioners of Fortifications, 1755–1770 (series S164001; hereafter JCF), 17 and 24 February 1757, 16 June 1757. This journal is also available on microfilm in the South Carolina History Room at the Charleston County Public Library.

[10] Lipscomb, Journal of the Commons House, 1755–57, 307–8 (26 January 1757), 366 (11 March 1757).

[11] South Carolina Gazette, 10 February 1757. In July 1757, after he had left Charleston, De Brahm drafted a new plat illustrating a revision of his 1755 plan and sent it to England for review: “Copy of Mr. De Brahm’s Plan for fortifying Charles Town, South Carolina, as now doing, with additions and Improvements, July 1757,” National Archives of the United Kingdom, CO 700/Carolina20. Note that the 1757 plat does not include a gateway in King Street, as the 1755 plan did, or any sort of gateway along the town’s northern boundary. This important omission suggests that De Brahm knew that the northernmost works in his Charleston plan would not be built.

[12] Alexander V. Campbell, The Royal American Regiment: An Atlantic Microcosm, 1755–1772 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), 31; South Carolina Gazette, 23 June 1757; Lipscomb, Journal of the Commons House, 1755–57, 479 (28 June 1757).

[13] Hess’s commission in the 62d Regiment (re-designated the 60th in early 1757) was dated 17 February 1756. See Worthington Chauncey Ford, comp., British Officers Serving in America, 1754–1774 (Boston: David Clapp & Son, 1894), 54. Note that Hess’s name is consistently spelled “Hesse” in contemporary South Carolina records, a fact that might reflect its local pronunciation.

[14] Lipscomb, Journal of the Commons House, 1755–57, 477–78 (27 June 1757).

[15] Lipscomb, Journal of the Commons House, 1755–57, 479 (28 June 1757).

[16] Lipscomb, Journal of the Commons House, 1755–57, 492–93 (6 July 1757). A part of these “new” barracks later became part of the College of Charleston.

[17] Col. Henry Bouquet to the Earl of Loudoun, 23 June 1757, in Sylvester K. Stevens and Donald H. Kent, eds., The Papers of Col. Henry Bouquet, series 21631 and 21632 (Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical Commission, 1941), 16.

[18] Act No. 866, “An Act granting to his Majesty an aid of one hundred and sixty thousand pounds current money, to defray the expense of raising, cloathing [sic] and maintaining for one year a regiment, to consist of seven companies of soldiers, each to be composed of one hundred men, besides officers, five of which companies to be employed as well in the immediate defence of South Carolina as in the general service of North America, and the other two companies to be employed wholly in the service of this Government; and to discharge the arrears due to the Provincials garrison at Fort Loudoun, and to pay for six months provisions for the said Provincials; and granting his Majesty the further sum of forty-four thousand three hundred pounds, for fortifying Charlestown and repairing and strengthening of Fort Johnson; and for stamping orders for the more expeditious issuing of the said sums, together with the further sum of twenty-five thousand pounds, heretofore granted to his Majesty for the use of the fortifications, and providing funds to call in and sink the said orders, within the times therein limited,” ratified on 6 July 1757. The text of this act was never published and does not survive in any archive in South Carolina. A contemporary copy sent to the Board of Trade survives among their records at the National Archive of the United Kingdom, CO 5/421. A microfilm copy thereof is available at SCDAH.

[19] See the two local news reports in South Carolina Gazette, 18 August 1757, and its supplement.

[20] JCF, 25 August 1757; Huntington Library, catalog reference HM15399

[21] JCF, 10 September 1757.

[22] JCF, 25 August 1757, 5 December 1757, 9 February 1758, 14 September 1758. Speaking of Fort Lyttelton in 1763, Dr. George Milligen-Johnston remarked that “the platforms and parapet wall not being finished for want of money.” See Chapman J. Milling, ed., Colonial South Carolina: Two Contemporary Descriptions by Governor James Glen and Doctor George Milligen-Johnston (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1951), 150.

[23] Bouquet to the Earl of Loudoun, 25 August 1757, in Papers of Henry Bouquet, series 21631 and 21632, 67.

[24] Bouquet to the Earl of Loudoun, 16 October 1757, Papers of Henry Bouquet, series 21631 and 21632, 113–14.

[25] JCF, 10 October 1757. This labor agreement is also mentioned in a letter from Bouquet to the Earl of Loudoun, dated 16 October 1757, in Papers of Henry Bouquet, series 21631 and 21632, 113–14.

[26] JCF, 27 October 1757, 8 November 1757, 20 July 1758. The formal conveyance of the Wragg-Manigault property to the provincial government was noted by the Commissioners of Fortifications in 1758, but never properly recorded at the office of the Register of Mesne Conveyance (now the Charleston County Register of Deeds).

[27] JCF, 2 November 1757, 12 November 1757.

PREVIOUS: The Horn Work: Marion Square’s Tabby Fortress

NEXT: The Rise of Charleston’s Horn Work, Part 2

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments