South Carolina's Capitation Tax on Free People of Color, 1756–1864

Processing Request

Processing Request

For more than a century before the Civil War, the State of South Carolina levied an annual “head” or “capitation” tax on all “free persons” of African descent. Those residing in Charleston were required to pay an additional head tax to the city government for more than seventy years. The assessment of these twin taxes varied greatly over the decades, and the paucity of extant records has clouded our understanding of their significance. Join me now for an overview of the legal framework and the surviving materials that illuminate a colorful minority of the local population.

Taxation, past or present, might not seem like an exciting topic of conversation, but the subject of this program is a curious phenomenon that was once an important aspect of life in the Charleston area. Tracing the history of the capitation tax is like following a trail of breadcrumbs that leads to a better understanding of a small but very significant class of people that once inhabited this community. If you’re interested in understanding the layers of society in early South Carolina in general, and Charleston in particular, the story of the capitation tax is essential reading.

South Carolina’s early tax laws were similar to those in force today. The colonial, then state, and then city governments assessed annual taxes on real property, vehicles, stock-in-trade, professional profits, interest-bearing bonds, and similar valuable assets—including enslaved people—owned by individual citizens. A capitation tax, also known as a “pole” or “head” tax, is an ancient sort of tax of a different character. It refers to a fixed sum levied on individuals without regard to property, income, or other assets. “Head” taxes were often used in the distant past during times of warfare or emergency to raise additional revenue for the local or regional government.

In contrast to many of the “head” taxes of the distant past, the capitation taxes levied in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century South Carolina constituted a not-so-subtle form of institutional racism. Although this stream of revenue did not begin as a surcharge on the right to be free, it evolved into a plainly prejudicial tax that was perpetuated by the discriminatory politics of antebellum South Carolina. Let’s begin our investigation by clarifying the racial language at the heart of this topic.

The surviving records of eighteenth and nineteenth century South Carolina use a variety of terms to describe the population in question. Persons who appeared to be of “pure” African descent were called “Negroes,” while those of mixed African and European ancestry were called “mulattoes.” Early South Carolinians used the Spanish word mestizo to describe persons of mixed African and Native American ancestry, although the term is frequently spelled “mustizo” or “mustee” in surviving records. When such people gained their freedom from slavery, through a variety of means (see Episodes No. 145 and No. 146), the law described them respectively as “free negroes,” “free mulattoes,” and “free mestizos.” South Carolinians of the late 1700s began using the phrase “free people of color” as a sort of catch-all term for non-white folks who were not enslaved.

Some legal scholars of the nineteenth century objected to the popular phrase “free person(s) of color,” however, on the grounds that persons described as “negroes” were technically “black” rather than “colored.” Similarly, a number of twentieth-century scholars have deployed the term “free black(s)” to describe this diverse population of negroes, mulattoes, and mestizos, although the majority of those people in the eighteenth and nineteenth century would have argued they were “colored” rather than “black.” For the sake of brevity, and to avoid confusion and controversy, I prefer to use the phrase “free person(s) of color” rather than “free black(s)” as an umbrella term to describe the free non-White people of early South Carolina.[1]

South Carolina’s first capitation tax emerged from a debate within the provincial government about the contents of the annual tax bill in the spring of 1756. In mid-February of that year, the White slaveholding members of the Commons House of Assembly resolved “that a poll-tax be imposed on all such Free Negros [sic], Mulattos & Mestizos in this province as have no property.” This suggestion was prompted by the observation that such people were generally very poor and therefore not incumbered by taxes levied on valuable assets.[2] The resulting tax law, ratified in July 1756, imposed a new tax of twenty-five shillings on “all free Negroes Mulattoes and Mestizos who do not pay any other part of the taxes imposed by this act.”

The capitation tax introduced by South Carolina’s provincial government in 1756 continued and evolved in subsequent years. It applied to free people of color, including both men and women, residing in the dense confines of urban Charleston and the most isolated and rural areas of the Lowcountry, Midlands, and Upstate. The collection of this “head” tax (like other taxes across South Carolina) lapsed during the years 1775 and 1776 as the existing colonial government morphed into a revolutionary and then sovereign government. The newly-organized state government resumed the practice of levying annual taxes in January 1777, but the collection of the capitation and other taxes again ceased during the British occupation of Charleston, 12 May 1780 to 14 December 1782. Following the reorganization of the South Carolina General Assembly in the spring of 1783, the legislature resumed the annual assessment of capitation and other taxes across the state.

During the post-war reconstruction of South Carolina’s infrastructure, some members of the General Assembly noted that many poor White males across the state also lived below the tax threshold that was based on property ownership. To extract a minimum tax contribution from that population in 1786 and 1787, the state legislature imposed a similar capitation tax on free White males (not females), aged twenty-one to fifty years of age, “who pay no other part of the taxes imposed” by the state. The sum levied on poor White men was nearly commensurate with that assessed on free persons of color, but it did not last. The General Assembly discontinued the White male capitation tax in the annual revenue bill of 1788. That same law extended the state’s capitation tax to include all free persons of color, including men and women, regardless of whether or not they paid any other state taxes on real estate, slaves, vehicles, or other assets.

During the post-war reconstruction of South Carolina’s infrastructure, some members of the General Assembly noted that many poor White males across the state also lived below the tax threshold that was based on property ownership. To extract a minimum tax contribution from that population in 1786 and 1787, the state legislature imposed a similar capitation tax on free White males (not females), aged twenty-one to fifty years of age, “who pay no other part of the taxes imposed” by the state. The sum levied on poor White men was nearly commensurate with that assessed on free persons of color, but it did not last. The General Assembly discontinued the White male capitation tax in the annual revenue bill of 1788. That same law extended the state’s capitation tax to include all free persons of color, including men and women, regardless of whether or not they paid any other state taxes on real estate, slaves, vehicles, or other assets.

From that point forward, South Carolina’s capitation tax continued as a residual burden, levied annually on a poor minority and perpetuated by racial prejudice. The people liable by law to pay the tax did not enjoy the right of suffrage and therefore lacked the ability to elect representatives to voice their opinions within the sphere of government. It was, in fact, a form of taxation without representation, levied and collected by veterans of the American Revolution. If free persons of color happened to own property or assets that were also liable to taxation, they probably paid a greater tax—in proportion to their income—than their White neighbors. Despite such inequities, South Carolina’s capitation tax survived well into the nineteenth century.

By the end of the 1780s, the free Black and Colored residents of urban Charleston witnessed a significant increase in their annual taxes. The City of Charleston was incorporated in August 1783, but the new City Council did not begin taxing free non-White residents for several years. The city introduced its own capitation tax in either 1789 or 1790 (the complete lack of extant municipal records from that era renders it impossible to determine the precise date).[3] Like the early state tax, Charleston’s municipal capitation tax initially applied only to free persons of color who paid no other form of city tax. Beginning with the tax ordinance of 1798, however, City Council followed the state’s example and required all such free persons to pay the head tax. From that point forward, all free persons of color residing within Charleston’s corporate limits paid an annual head tax to both the city treasurer and the state treasurer, in addition to any other taxes on property, assets, or professional income levied on all citizens regardless of skin color.

The annual capitation taxes imposed by the City of Charleston and the State of South Carolina evolved over the decades and continued into the period of the American Civil War.[4] Charleston’s City Council ratified its final capitation tax in February 1864 and required free persons of color to render their respective payments in June of that year. Similarly, the South Carolina General Assembly’s final capitation tax, ratified in December 1864, directed free persons of color across the state to render their payments during the month of April 1865. Owing to the collapse of the Confederate government and the demise of the institution of slavery that spring, however, the tax was not collected.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve scoured several hundred pages of boring tax legislation in an effort to assemble this overview of the capitation tax. Some of the details found within those pages is rather interesting, while much of it is repetitive and occasionally convoluted. In the interest of time, I’d like to continue by addressing some of the most salient features of the evolving tax code.

Ages of Tax Liability:

South Carolina’s capitation tax of 1756 applied to free persons of color in general, but all subsequent acts narrowed the liable population to a specific age bracket that evolved over time. From 1757 through 1784, the state tax applied to all free persons of color from ten to sixty years of age. From 1785 through 1803, this age bracket was reduced to the ages of sixteen to fifty years. From 1804 through 1864, all free persons of color in South Carolina from fifteen to fifty years of age were liable to pay the annual capitation tax.

The City of Charleston’s early capitation laws did not specify an age range of tax liability until 1795, when it limited the tax to free persons of color between the ages of sixteen and fifty. That restriction was deleted in 1796, but returned in 1804, at which time the age bracket was fixed at fifteen to fifty years of age. The city revised the age bracket in 1808 to embrace free persons aged eighteen to fifty, and changed again in 1812 to include people fifteen to sixty years of age. In short, there was a great deal of variation. From 1812 into the early 1860s, the city’s capitation ordinances experimented with an evolving slate of multiple age brackets that varied according to job description, residency, and sex. At some point in the near future, I’ll condense these details into a table that I’ll add to the text version of this podcast.

The City of Charleston’s early capitation laws did not specify an age range of tax liability until 1795, when it limited the tax to free persons of color between the ages of sixteen and fifty. That restriction was deleted in 1796, but returned in 1804, at which time the age bracket was fixed at fifteen to fifty years of age. The city revised the age bracket in 1808 to embrace free persons aged eighteen to fifty, and changed again in 1812 to include people fifteen to sixty years of age. In short, there was a great deal of variation. From 1812 into the early 1860s, the city’s capitation ordinances experimented with an evolving slate of multiple age brackets that varied according to job description, residency, and sex. At some point in the near future, I’ll condense these details into a table that I’ll add to the text version of this podcast.

Value of the Capitation Taxes:

The initial capitation tax of 1756 assessed the sum of twenty-five shillings (South Carolina currency) on all free persons of color within the colony. The amount of the state tax varied greatly in every subsequent year through 1794, but was always rendered in shillings and pence in the British fashion. The state government switched to the new national currency in 1795 and that year assessed a capitation tax of two U.S. dollars ($2) on free persons of color. Increased state spending during the War of 1812 resulted in a capitation tax of $3 in 1814, but the annual state assessment was reduced to $2 in 1815. The price rose to $2.75 in 1858, and then to $3 in 1860. Switching to Confederate currency during the Civil War, the state capitation tax of 1863 increased to $6.75 and then to $10 in 1864.

Tracking the value of the annual capitation taxes assessed by the City of Charleston is much more difficult than that of the state tax. Like the state capitation tax, the municipal version was a flat sum rendered in shillings and pence that varied greatly through the year 1795. The city began requiring tax payments in United States currency in 1796, but the rate of city assessment did not stabilize like the state tax. Beginning in 1798, the city began applying different tax rates to different subsets of the target population based on an evolving system of age brackets. The details of this evolution are simply too tedious and confusing for words, so I’m planning to create a table to summarize the facts. Keep your eye on the text version of this podcast for the results.

Exemptions from the Capitation Taxes:

Beginning in 1809 and continuing through the era of the American Civil War, the state granted a capitation tax exemption to individuals who could prove, to the satisfaction of the tax collector, that they were “incapable, from maims or otherwise,” of earning a livelihood for themselves. The City of Charleston adopted a similar provision in 1816, which likewise continued through the end of 1864.

Anecdotal notes recorded on the surviving ledgers of the annual capitation tax and among the Miscellaneous Records of the Secretary of State (now held at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History) document a curious pattern of exemptions that merits a separate conversation: Tax collectors working for both the state and city governments evidently waived the capitation tax liability of free persons of color who could prove that they were descended from “free Indians in amity with the state.” In other words, these exempted individuals produced documents and/or the testimony of sworn White witnesses to prove that their respective mothers, grandmothers, or great-grandmothers were free Indians. Even if they appeared to be dark-skinned mestizos or “mustees,” their maternal lineage entitled them to be recognized as free people who were not liable to pay the capitation taxes imposed by the City of Charleston and the State of South Carolina. By this practice, frugality motivated free persons of color to investigate and perhaps even fabricate facts related to their family history.[5]

A final exemption emerged during the embattled years of the American Civil War. In the state tax bills of 1862, 1863, and 1864, the South Carolina General Assembly waived the collection of capitation tax from all free persons of color who participated in the state army or that of the Confederate States of America. Owing to the paucity of extant records from this era, however, it’s unclear how many men qualified for this novel form of tax relief.

The Consequences of Non-Payment:

The earliest iterations of the state and city capitation laws did not articulate any specific action against free persons of color who neglected or refused to pay the annual capitation tax. In general, the state and city governments followed the traditional legal protocol against defaulters: the treasurer issued a writ of execution against the defaulter, which empowered the local sheriff to seize and sell at auction a portion of the defaulter’s property to satisfy the tax debt.

Because many free people of color were poor and owned little property, real or personal, however, the state and city governments eventually devised additional means of collecting the taxes in question. In this regard, the City of Charleston acted decades before the state followed suit. Beginning in 1799, failure to pay the city capitation tax could result in a brief period of incarceration. “Should no property be found for the purpose of raising the said tax” by traditional writ of execution, said the ordinance of March 1799, “the city treasurer is hereby authorized to issue an execution against the body of such person or persons as neglect or refuse to pay the aforesaid tax; and every such person or persons shall be committed to the Work House, there to continue for any time not exceeding two months, unless such tax with costs be sooner paid.” In the tax ordinance of 1804 and subsequent years, the city reduced this period of incarceration to one month. Beginning in 1827 and continuing through the Civil War, the city tax ordinances specified that defaulters confined to the notorious Work House would be “placed on the tread mill,” a grueling but non-violent form of punishment that sapped the subject’s physical strength.[6]

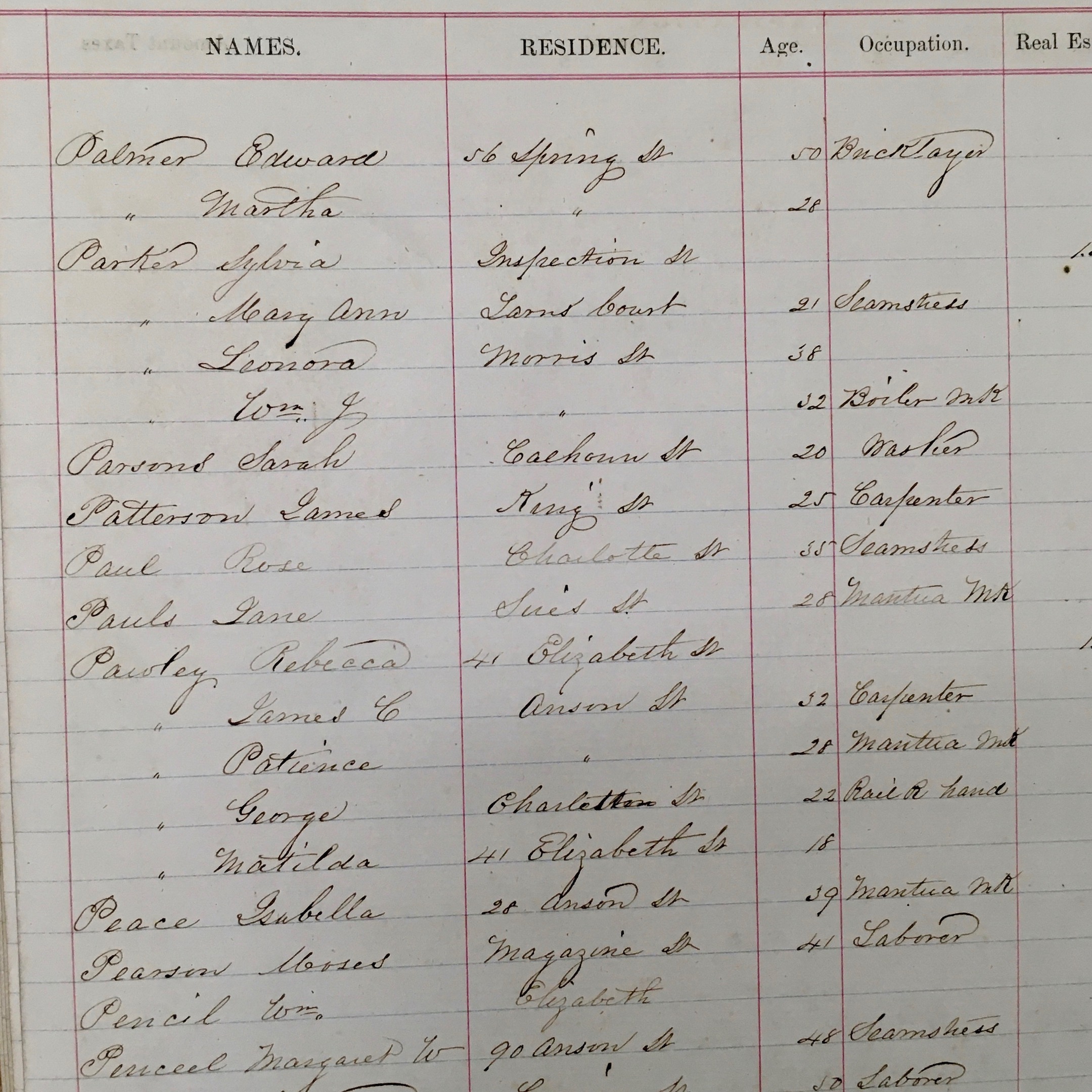

As a corollary to this Charleston practice, it’s worth noting that the city tax ordinance of 1799 introduced an additional obligation on free persons of color. Henceforth, they were required to register annually their name, “place of abode,” and occupation in a specific book at the treasurer’s office. An 1804 revision also required them to list the names of their children, and in 1806 required them to state their age and the ages of their children. Failure to comply with such requirements in 1799 resulted in up to three weeks incarceration at the Work House, but the tax ordinance of 1804 and subsequent years softened this punishment to a doubling of the capitation tax.

Beginning in December 1830 and continuing to the end of the Civil War, the South Carolina General Assembly authorized and required the sheriff of every district in the state to file an execution against every free person of color who refused or neglected to pay their annual capitation tax, and to sell “their service” for a term not exceeding one year; “provided,” however, “that the sheriff shall not sell the services of any such person for a longer term than shall be necessary to pay the taxes due and costs.”[7] Records of such sales of temporary servitude do not appear among the surviving records of the capitation tax, but might exist in other records created at the county level across the state.

The Surviving Records:

I’ve constructed this overview of South Carolina’s capitation taxes by collating data found in more than one hundred and eighty statutes and ordinances created by the colonial, state, and city governments between 1756 and 1864. Almost all of the state-level tax laws are readily available in a collection of published volumes called The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, all of which have been scanned and are now available online.[8] There is currently no similar unified collection of Charleston’s early ordinances, but the text of most of the city’s capitation tax laws can be found in various digests published in the nineteenth century and in contemporary newspapers. Like the state laws, these city-specific materials have been largely digitized and are accessible on the Internet.[9]

I’ve constructed this overview of South Carolina’s capitation taxes by collating data found in more than one hundred and eighty statutes and ordinances created by the colonial, state, and city governments between 1756 and 1864. Almost all of the state-level tax laws are readily available in a collection of published volumes called The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, all of which have been scanned and are now available online.[8] There is currently no similar unified collection of Charleston’s early ordinances, but the text of most of the city’s capitation tax laws can be found in various digests published in the nineteenth century and in contemporary newspapers. Like the state laws, these city-specific materials have been largely digitized and are accessible on the Internet.[9]

As for the records of the collection and payment of the various capitation taxes over the span of more than a century, only a fraction of the original materials are now extant. The names and other personal data recorded in the earliest capitation tax ledgers, dating from 1756 through at least 1810, no longer survive in any form. Twenty-nine volumes or ledgers of state capitation taxes collected within the City of Charleston between circa 1811 through 1860 are now held at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia. The names contained in each volume appear in alphabetical order, and often (but not always) include the age, address, and occupation of each taxpayer. The state archive microfilmed these materials in the early 1980s, along with a brief but very useful pamphlet that summarizes the historical context of the extant materials.[10]

In addition to these state materials, the Charleston Library Society currently holds two volumes of city capitation tax ledgers, dated 1862 and 1863, and the archive of the Charleston County Public Library holds three similar volumes dated circa 1853 (lower wards only), 1861, and 1864. The City of Charleston created a microfilm copy of these additional five volumes in 2004. Researchers can access both the state and city microfilm of these capitation tax ledgers through the South Carolina History Room at the main branch of the Charleston County Public Library.

Conclusion:

My goal in constructing this program was to provide an overview of a complex topic that has not yet received the level of attention that it deserves. I hope I’ve expanded our collective understanding of the capitation tax a bit, but there’s still room for future scholars to continue the research. In the meantime, I encourage anyone who’s interested in this topic to visit the South Carolina History Room at CCPL, and/or the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia to take a look at the primary source materials in person.

My goal in constructing this program was to provide an overview of a complex topic that has not yet received the level of attention that it deserves. I hope I’ve expanded our collective understanding of the capitation tax a bit, but there’s still room for future scholars to continue the research. In the meantime, I encourage anyone who’s interested in this topic to visit the South Carolina History Room at CCPL, and/or the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia to take a look at the primary source materials in person.

The extant volumes of capitation tax ledgers contain unique information related to several thousand individuals who once lived and worked in the City of Charleston. This material represents a treasure trove of genealogical information, and supplies social and political historians with valuable raw material for studying the demographics of antebellum Charleston. The laws that created and shaped these tax records also help us understand the legacy of race-based prejudice that once dominated the social fabric of South Carolina. Pound for pound and page for page, I consider these venerable tax records to be among the most valuable relics of our community’s past.

[1] For an antebellum discussion of this terminology, see Chapter 1, sections 5, 6, 10, 13, 15, 19–29, 45–56 of John Belton O’Neall, The Negro Law of South Carolina (Columbia, S.C.: John G. Bowman, 1848).

[2] Terry W. Lipscomb, ed., The Colonial Records of South Carolina: The Journal of the Commons House of Assembly, November 20, 1755–July 6, 1757 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press for the South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1989), 112, 187 (18 February and 31 March 1756).

[3] Charleston’s municipal tax ordinance of 13 March 1788 does not mention free persons of color, but the tax ordinance of 3 December 1790 does. Between these two laws, the City Council ratified tax ordinances on 22 January 1789 (for the year 1789) and 19 December 1789 (for 1790), but the texts of those ordinances cannot now be found in any format (because of the “Great Memory Loss of 1865”). The earliest municipal tax on free persons of color in Charleston appeared, therefore, either in 1789 or 1790.

[4] Curiously, the state tax statutes of 1855 and 1856 extended the capitation tax to “Egyptians and Indians, (free Indians in amity with this government excepted),” but omitted this provision in the tax laws of 1857 and subsequent years.

[5] The city tax ordinances of 1812 and 1813 both contain text specifically extending the capitation tax to free persons color, “whether a descendant of an Indian or otherwise.” The introduction of this clause strongly suggests that exceptions had been made prior to 1812, and the discontinuance of this clause after 1813 strongly suggests that the practice resumed in 1814. The texts of these ordinances, ratified on 8 April 1812 and 14 April 1713 respectively, are not found in any published sources, but appear in [Charleston, S.C.] City Gazette, 9 April 1812 and 17 April 1813.

[6] Each of the city tax ordinances of 1799 through 1843 contain text relative to the treatment of defaulters, but this text is absent from the annual tax ordinances of 1844 through 1864. Despite this omission, the City Council of Charleston continued the practice of punishing tax defaulters, including potential incarceration at the Work House, via a standing ordinance that continued in force throughout the period in question. See Section 20 of “An Ordinance to regulate the collection of the city taxes, prescribing the duties of certain city officers, and for other purposes,” ratified on 12 March 1844, in George B. Eckhard, comp. A Digest of the Ordinances of the City Council of Charleston, from the Year 1783 to October 1844 (Charleston, S.C.: Walker & Burke, 1844), 276.

[7] This instruction regarding defaulters appears in the text of the annual tax statutes from 1830 through 1843. Like the City of Charleston, the South Carolina General Assembly in 1844 enacted at separate law containing instructions regarding a number of tax-collecting protocol, including the sale of the service of defaulting free persons of color. See Section 2 of Act No. 2885, “An Act prescribing the duties of certain officers in the collection of supplies, the payment of salaries, and for other purposes,” in The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 11 (Columbia, S.C.: Republican Printing Company, 1873), 267. Following that change in 1844, which remained in force through the Civil War, the legislature omitted the text in question from the annual tax statutes of 1845–1864.

[8] In volumes 4–6 and 11–13 of The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, see tax acts No. 856 (for 1756), 865 (1757), 888 (1759), 898 (1760), 909 (1761), 925 (1762), 935 (1764), 940 (1765), 951 (1766), 962 (1767), 979 (1768), 990 (1769), 1034 (1777), 1077 (1778), 1131 (1779), 1159 (1783), 1234 (1784), 1284 (1785), 1312 (1786), 1370 (1787), 1384 (1788), 1468 (1789), 1487 (1790), 1524 (1791), 1550 (1792), 1573 (1793), 1607 (1794), 1634 (1795), 1659 (1796), 1692 (1797), 1707 (1798), 1738 (1799), 1755 (1800), 1784 (1801), 1803 (1802), 1822 (1803), 1838 (1804), 1875 (1805), 1887 (1806), 1908 (1807), 1933 (1808), 1960 (1809), 1978 (1810), 2001 (1811), 2022 (1812), 2041 (1813), 2066 (1814), 2094 (1815), 2128 (1816), 2172 (1817), 2207 (1818), 2229 (1819), 2247 (1820), 2274 (1821), 2300 (1822), 2327 (1823), 2356 (1824), 2383 (1825), 2403 (1826), 2439 (1827), 2468 (1828), 2497 (1829), 2521 (1830), 2553 (1831), 2584 (1832), 2614 (1833), 2644 (1834), 2671 (1835), 2711 (1836), 2741 (1837), 2770 (1838), 2772 (1839), 2804 (1840), 2830 (1841), 2857 (1842), 2884 (1843), 2922 (1844), 2948 (1845), 2966 (1846), 3005 (1847), 3051 (1848), 3067 (1849), 4002 (1850), 4036 (1851), 4074 (1852), 4126 (1853), 4173 (1854), 4220 (1855), 4258 (1856), 4331 (1857), 4388 (1858), 4434 (1859), 4496 (1860), 4566 (1861), 4611 (1862), 4667 (1863), 4699 (1864). In addition to these published sources, engrossed copies of the manuscript tax acts, including the unpublished tax acts of 1756–57 and 1770–74, are held at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

[9] See the bibliography of the “Published Ordinances of the Charleston City Council.”

[10] Judith Brimelow and Michael E. Stevens, State Free Negro Capitation Tax Books, Charleston, South Carolina, ca. 1811–1860; an introduction to accompany South Carolina Archives Microcopy No. 11 (Columbia: South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1983). One of the twenty-nine volumes included in this collection is held by the Library of Congress.

NEXT: The Colonial Roots of Black Barbers and Hairdressers

PREVIOUSLY: Five Years of Charleston Time Machine

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments