The State Flag of South Carolina: A Banner of Hope and Resilience

Processing Request

Processing Request

The recent publication of a report about the state flag of South Carolina had inspired many citizens to express their displeasure with proposed changes to its design. The Palmetto State has one of the most recognizable flags in the nation, and no one wants to diminish its acknowledged visual appeal. Less familiar, however, are the details of the flag’s creation and the meaning of its distinctive crescent and palmetto tree. Today we’ll explore the background of flags and symbols in early South Carolina that led to the creation of a proud blue banner of hope and resilience.

I’d like to preface this program by acknowledging the hard work that went into the production of the recent reports of the South Carolina State Flag Study Committee, which was appointed by the legislature in 2018. Their work has inspired me to gather together a number of historical crumbs that I’ve collected over the years and attempt to weave them into a coherent narrative. A large number of writers have touched on the history of the South Carolina flag over the past two centuries, but I believe I’ve found a few details and connected a few dots that others have missed. I certainly don’t claim to have all the answers about the history of the state flag, and I believe that a certain amount of mystery will always hang of the decisions that led to its creation in 1775. Despite the lingering ambiguities, however, there is a trail of clues that suggest a thread of continuity and logic behind the design of our famous blue flag.

The Heraldic Background

The crescent and the palmetto tree on the state flag of South Carolina are symbols rooted in an ancient language of pictographs that arose in Western Europe many centuries ago. In England, the parent-nation of South Carolina, this language is usually identified under the term “heraldry.” Although the people of early Carolina inherited the language and traditions of heraldry from the colony’s English roots, the practice was derived from a shared vocabulary of symbols familiar to earlier cultures of Saxons, Danes, Franks, Goths, Romans, Greeks, Phrygians, Egyptians, and others.

The art and language of heraldry, complete with its own syntax and vocabulary of symbols and figures, was first applied to the defensive shields carried into battle by warriors, knights, and persons of quality. For this reason, a heraldic design used by a specific individual or family is known as a “coat-of-arms.” In the late fifteenth century, the English monarchy established an office, now called the College of Arms, to collect and regulate the use of heraldic designs among the nobility and their knights. Firearms rendered battle shields superfluous around the turn of the sixteenth century, and the tradition of designing heraldic shields evolved into a largely ceremonial practice. Possession of an officially-recognized coat-of-arms—once restricted to the highest ranks of English society—became an increasingly desirable status-symbol that identified its owner as a member of the genteel class of ladies and gentlemen.

The crescent, for example, is an ancient symbol that has been used by many different cultures. As its name and shape suggest, the crescent refers to a crescent moon, which forms part of a grouping of heraldic devices known as “celestials” (including the sun, stars, comets, etc.). The points or “horns” of a crescent normally point upward, but other orientations have been used in the distant past. A crescent rotated ninety degrees to the viewer’s left, the most common variation, resembles a waxing crescent moon, or increscent in Latin (from which we derive the word “increasing”). Less frequently, the crescent may be turned to the viewer’s right, resembling a waning moon or decrescent (the root of the word “decreasing”). The infrequently-seen upside-down crescent is called a crescent reversed. Whether upright or in the increscent position, the ancient meaning of this heraldic symbol remains constant. The crescent, representing the waxing harvest moon, expresses the hope of increasing prosperity or the hope of future glory. In the words of one heraldic expert writing in 1765, the waxing crescent “signifies the rising of Families, and even of States, for which reason it is bor’n so by the Turks.”[1]

The crescent, for example, is an ancient symbol that has been used by many different cultures. As its name and shape suggest, the crescent refers to a crescent moon, which forms part of a grouping of heraldic devices known as “celestials” (including the sun, stars, comets, etc.). The points or “horns” of a crescent normally point upward, but other orientations have been used in the distant past. A crescent rotated ninety degrees to the viewer’s left, the most common variation, resembles a waxing crescent moon, or increscent in Latin (from which we derive the word “increasing”). Less frequently, the crescent may be turned to the viewer’s right, resembling a waning moon or decrescent (the root of the word “decreasing”). The infrequently-seen upside-down crescent is called a crescent reversed. Whether upright or in the increscent position, the ancient meaning of this heraldic symbol remains constant. The crescent, representing the waxing harvest moon, expresses the hope of increasing prosperity or the hope of future glory. In the words of one heraldic expert writing in 1765, the waxing crescent “signifies the rising of Families, and even of States, for which reason it is bor’n so by the Turks.”[1]

To understand the design and meaning of the state flag of South Carolina, we’ll need a few more terms from the arsenal of heraldry and vexillology to inform our narrative. In describing a coat-of-arms or flag, the background shape and color are known as the “escutcheon” or “field.” Onto this field are placed one or more figures called “charges” and, often, a shape (like a chevron or a lozenge) known as an “ordinary.” Because men passed their coat-of-arms to their sons, the practice of heraldry adopted a visual vocabulary to indicate the sequence of their births. This system of “cadency” employed various symbols to indicate the first son, second son, and so on, to the ninth male heir. The traditional cadence symbol for a second son, like me, is a crescent, while the symbol for a third son, like George Washington, is a five-pointed star called a “mullet” (as seen on the flag of the United States of America).

To understand the design and meaning of the state flag of South Carolina, we’ll need a few more terms from the arsenal of heraldry and vexillology to inform our narrative. In describing a coat-of-arms or flag, the background shape and color are known as the “escutcheon” or “field.” Onto this field are placed one or more figures called “charges” and, often, a shape (like a chevron or a lozenge) known as an “ordinary.” Because men passed their coat-of-arms to their sons, the practice of heraldry adopted a visual vocabulary to indicate the sequence of their births. This system of “cadency” employed various symbols to indicate the first son, second son, and so on, to the ninth male heir. The traditional cadence symbol for a second son, like me, is a crescent, while the symbol for a third son, like George Washington, is a five-pointed star called a “mullet” (as seen on the flag of the United States of America).

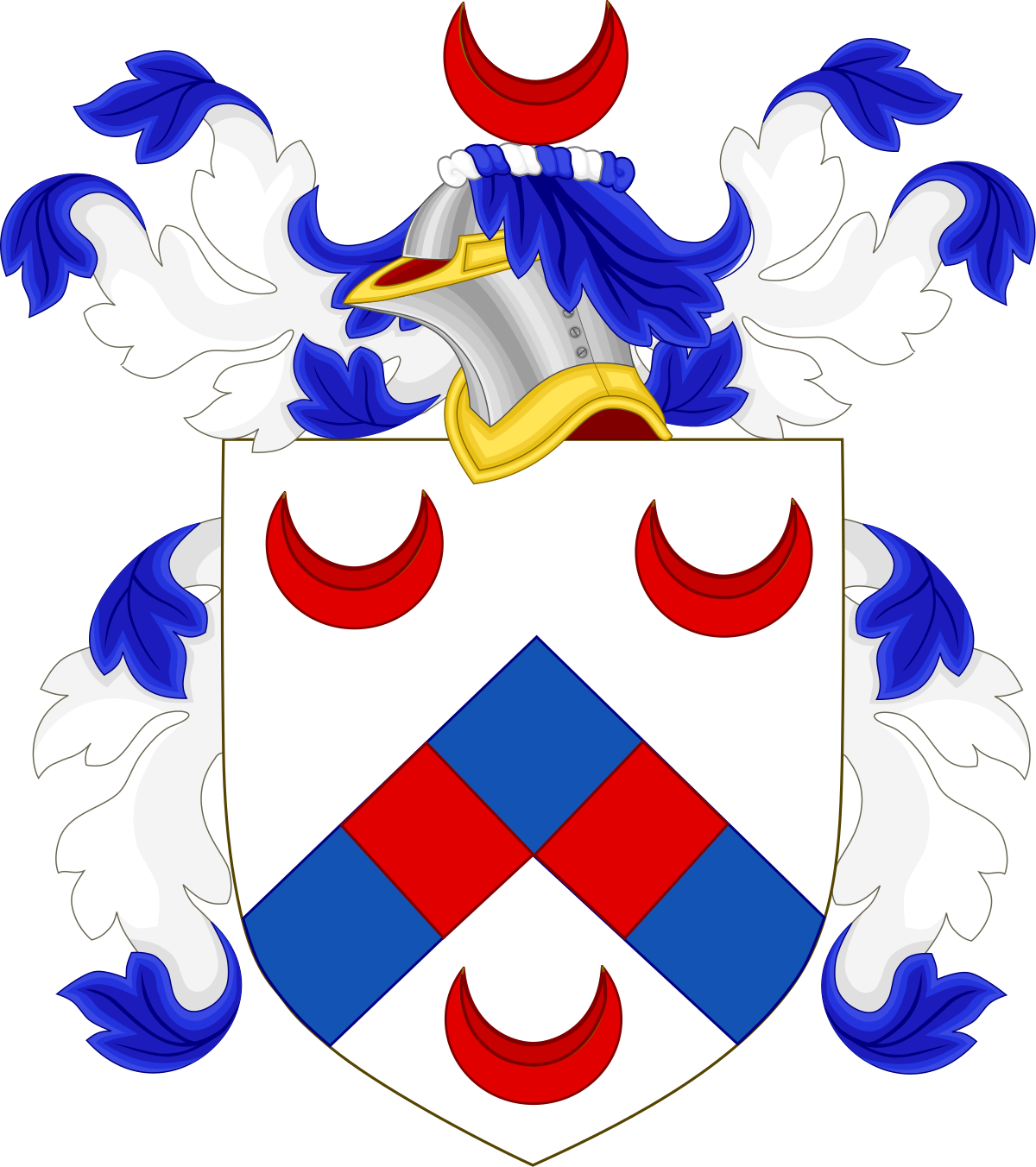

I’ll mention a few local examples to illustrate these points. The coat-of-arms borne by the first Lieutenant Governor William Bull (1683–1755) of South Carolina featured a red field with a single charge in the center—a man’s arm holding an upright sword. Above this escutcheon appeared a crest featuring a bull. The second Lieutenant Governor William Bull (1719–1791) of South Carolina, who was the second son of his father, added a crescent to the field of his coat-of-arm to indicate his cadency. The design of the coat-of-arms used by Governor John Rutledge (1739–1800), by contrast, included a white field charged with three red crescents divided or “parted” by a chevron, all of which was surmounted by a crest featuring an additional red crescent.

A large portion of heraldic language was also applied to the design of early flags carried into battle, such as pennons, banners, standards, and ensigns. This parallel practice evolved its own set of rules and customs, the study of which is today known by the Latin term vexillology. In the shared language of heraldry and vexillology, all spatial directions are given in Latin and described from the perspective of the person who bears or carries the shield or flag in question. The bearer’s right or dexter side is, therefore, the viewer’s left, and the bearer’s left or sinister side is the viewer’s right. The two upper-most corners of the shield or flag are called cantons. In the design of heraldic shields and flags, the principal charge is normally placed in the center of the field (like the palmetto tree in the South Carolina state flag), while a subordinate figure commonly appears in the dexter canton (as the crescent in the state flag). Because the dexter canton is adjacent to the flagstaff, or “hoist” side of a flag, the symbol or figure in that corner is at least partially visible when the flag is resting in still air.[2]

A large portion of heraldic language was also applied to the design of early flags carried into battle, such as pennons, banners, standards, and ensigns. This parallel practice evolved its own set of rules and customs, the study of which is today known by the Latin term vexillology. In the shared language of heraldry and vexillology, all spatial directions are given in Latin and described from the perspective of the person who bears or carries the shield or flag in question. The bearer’s right or dexter side is, therefore, the viewer’s left, and the bearer’s left or sinister side is the viewer’s right. The two upper-most corners of the shield or flag are called cantons. In the design of heraldic shields and flags, the principal charge is normally placed in the center of the field (like the palmetto tree in the South Carolina state flag), while a subordinate figure commonly appears in the dexter canton (as the crescent in the state flag). Because the dexter canton is adjacent to the flagstaff, or “hoist” side of a flag, the symbol or figure in that corner is at least partially visible when the flag is resting in still air.[2]

The Common Flag of Colonial South Carolina

The ships visiting Charleston in the late seventeenth century and the fortifications erected here during that era flew the common English flag, which featured a red cross on a white field, known as St. George’s Cross. The political union of England and Scotland in 1707 prompted the creation of a new flag for the combined crowns of the new Kingdom of Great Britain. The flag formally adopted at that time combined the red cross of St. George with the white saltire (X) of St. Andrew on a blue field, the product of which became known as the Union Jack. Neither the warships of the Royal Navy nor merchant vessels in private commerce were permitted to fly the plain Union Jack, however, because that flag was considered to be part of the exclusive heraldry of the royal family. Instead, British ships flew what known as the “Red Ensign,” a rectangular red flag with the Union Jack placed in the dexter canton; that is, in the upper corner of the field next to the flagstaff.[3]

In the American colonies, provincial vessels and provincial fortifications often flew a modified version of the Red Ensign. In Charleston harbor between 1707 and 1775, one would have seen a blue version, complete with the Union Jack in the dexter canton, flying from the stern of merchant ships and above the forts and bastions around the harbor. Bishop Roberts’s watercolor painting of the Charleston waterfront, created in the mid-1730s and now in the collections of Colonial Williamsburg, clearly depicts a number of these “blue ensigns” that were not officially recognized by the British government of that era.[4]

Roberts’s painting, which was engraved in London and published without color in 1739, shows a large blue ensign flying above Granville Bastion at the south end of East Bay Street, but it does not include a depiction of Fort Johnson (built 1708–1709). Because that defensive structure on James Island played a significant role in guarding the harbor during most of the eighteenth century, however, we can safely assume that a similar blue ensign flew over Fort Johnson in the decades before the American Revolution.

Roberts’s painting, which was engraved in London and published without color in 1739, shows a large blue ensign flying above Granville Bastion at the south end of East Bay Street, but it does not include a depiction of Fort Johnson (built 1708–1709). Because that defensive structure on James Island played a significant role in guarding the harbor during most of the eighteenth century, however, we can safely assume that a similar blue ensign flew over Fort Johnson in the decades before the American Revolution.

Early Crescents in South Carolina

At the time of the South Carolina tricentennial in 1970, military historian Fitzhugh McMaster stated that the crescent had been used on local militia uniforms as early as 1760, but his assertion was based on flawed information and is not supported by any known documents from that era.[5] Another report of crescents being used in South Carolina pertains to an event that allegedly took place on James Island in October 1765, but was first described in 1821 by former governor John Drayton (1766–1822) in the published memoirs of his late father, William Henry Drayton (1742–1779). In this story, which took place during the Stamp Act crisis of 1765, a group of unidentified “volunteers” from the local population infiltrated Fort Johnson on James Island under the cover of darkness and hoisted a new flag up the fort’s flagstaff. Drayton described the banner as “a flag showing a blue field with three white crescents, which the volunteers had brought with them for the purpose.”[6] The symbolic meaning of the crescents and their arrangement on this flag is unclear, however, and the story of its brief appearance in 1765 was not described in any other contemporary source. Considering that this event took place during the meeting of the first Stamp Act Congress in New York, however, it is possible that the three crescents might have represented the three delegates from South Carolina attending that meeting—Christopher Gadsden, Thomas Lynch, and Edward Rutledge.[7]

A more concrete use of the crescent symbol appeared in one of the Charleston newspapers in the spring of 1773, when Lieutenant Governor William Bull authorized the creation of a new militia company of light infantry. The new unit, commanded by Captain Macartan Campbell (ca. 1748–1793), was actually the second light infantry company created in Charleston, and the eighth company in the urban militia regiment then commanded by Colonel Charles Pinckney (1732–1782). According to a newspaper report of the company’s proposed uniform, published in May 1773, the new light infantrymen were to wear “small beaver caps with black feathers, [and] a silver crescent on the front of the cap, inscribed Pro Patria” (“for my country”).[8]

Two years later, in the spring of 1775, South Carolina and the other colonies to the North began to break free from the political control of Great Britain. Fear of an impending military clash inspired an unofficial legislative body calling itself the South Carolina Provincial Congress to form a functioning shadow government. That June, the Provincial Congress established a “Council of Safety” to hold executive power and authorized the creation of several new regiments of provincial troops. According to reliable contemporary sources, the uniforms for these troops, or at least of the 1st and 2nd Regiments, included a silver crescent on the front of their caps. This feature was likely inspired by the crescents worn by the Charleston Light Infantry in 1773, and, like that earlier model, the cap crescents of the new regiments were allegedly inscribed with a motto: the word “Liberty.” We’ll return to this motto-and-crescent theme shortly.

The Origin of the Crescent Flag in 1775

During the early morning hours of September 15th, 1775, a detachment from the South Carolina 2nd Regiment captured Fort Johnson on James Island without resistance. In the course of the following week, other companies from both the 1st and 2nd Regiments moved across Charleston harbor and encamped around the fort. Here, I’ll let William Moultrie tell his famous story about the creation of South Carolina’s state flag. At that moment, Colonel Moultrie was in command of both the 1st and 2nd Regiments, as Christopher Gadsden, colonel of the 1st Regiment, was then in Philadelphia attending the Continental Congress. In his memoirs, published in 1802, Moultrie recalled the creation of the state flag in the following words:

“A little time after we were in possession of Fort Johnson [that is, late September or October 1775], it was thought necessary to have a flag for the purpose of signals: (as there was no national or state flag at that time) I was desired by the Council of Safety to have one made, upon which, as the state troops were clothed in blue, and the fort was garrisoned by the first and second regiments, who wore a silver crescent on the front of their caps; I had a large blue flag made with a crescent in the dexter corner, to be in uniform with the troops: This was the first American flag which was displayed in South Carolina.”[9]

William Moultrie’s brief account of the flag’s creation roots the story to a specific time and place, but his memoir leaves other questions unanswered. He did not offer any explanation of the crescent’s meaning, nor did he mention whether the word “Liberty” appeared on the flag (and if so, where on the blue field it was placed). Neither did Moultrie articulate the orientation of the crescent on the flag. Did its horns point upwards, or did it point to the viewer’s left, as an “increscent”? We’ll leave these questions for a moment and continue our narrative.

Funding the new provincial regiments and shadow government required lots of capital, so the South Carolina Provincial Congress began issuing paper money in the early months of the Revolution. On November 15th, 1775, apparently just a few days or weeks after William Moultrie created his famous flag, the Provincial Congress in Charleston authorized the printing of paper bills in various denominations. The newly-engraved note for £2.10.0 current money of South Carolina, a copy of which survives at the University of Notre Dame, includes a prominent image of a crescent below two crossed sabers, all surmounted by the Latin moto Pro Libertate (“for liberty”).[10] This small paper image seems to confirm the use of the crescent in conjunction with the word “Liberty” that is alleged to have appeared on both the caps of Moultrie’s 2nd Regiment and the blue flag he created in the autumn of 1775. Whether the physical relationship of the crescent and the word “Liberty” on the flag matched this paper bill remains unclear for the moment, however.

Moultrie’s flag with the crescent might have been novel, but the use of blue cloth for flags was not. As I mentioned earlier, sailing vessels and fortifications in Charleston harbor had been flying blue flags for decades before the beginning of the American Revolution. In early 1776, for example, the South Carolina Council of Safety asked William Moultrie and the other regimental commanders in Charleston harbor to devise a system of signals to communicate information between the various forts and observers in the town.[11] On March 9th, Colonel Christopher Gadsden distributed instructions for the proposed system to all units in the area. If one of the coastal lookouts observed a coastal schooner or sloop approaching Charleston harbor, Fort Johnson was ordered to “hoist the old common blue fort flagg, or jack.” If an enemy warship appeared on the coast, however, they would hoist “the new provincial flagg.”[12]

Moultrie’s flag with the crescent might have been novel, but the use of blue cloth for flags was not. As I mentioned earlier, sailing vessels and fortifications in Charleston harbor had been flying blue flags for decades before the beginning of the American Revolution. In early 1776, for example, the South Carolina Council of Safety asked William Moultrie and the other regimental commanders in Charleston harbor to devise a system of signals to communicate information between the various forts and observers in the town.[11] On March 9th, Colonel Christopher Gadsden distributed instructions for the proposed system to all units in the area. If one of the coastal lookouts observed a coastal schooner or sloop approaching Charleston harbor, Fort Johnson was ordered to “hoist the old common blue fort flagg, or jack.” If an enemy warship appeared on the coast, however, they would hoist “the new provincial flagg.”[12]

From this description of orders issued in early 1776, we might extrapolate a new theory: William Moultrie’s decision to use blue cloth to create a provincial flag was probably inspired by more than a desire to be “in uniform” with the color of the jackets worn by his troops. The flag he created in late 1775 also represented a rather simple modification of a traditional banner. The “old common blue fort flagg” mentioned in 1776 was likely the “blue ensign” familiar to generations of Charlestonians since the union of England and Scotland in 1707. By replacing the Union Jack in the flag’s dexter canton with a single white crescent, Moultrie merged a local vexillological tradition with an ancient heraldic symbol. The result was a unique and attractive banner that represented a budding new state endowed with great hopes for rising success.

It is lamentable that neither William Moultrie nor any of his contemporaries articulated their understanding of the crescent’s symbolic meaning. Perhaps the educated men and women of South Carolina, imbued with a better understanding of English heraldic traditions than later generations, pointed to the new flag flying over the forts in Charleston harbor and understood immediately its symbolism. More in touch with the seasonal cycles of agriculture than twenty-first century spectators, they might have recognized the sickle-shaped crescent as an ancient reference to the harvest moon and its traditional message of hope for an abundant future. In John Drayton’s 1821 publication of his father’s memoirs, the son included a footnote that suggests such an understanding. Reflecting on the coincidence of a crescent flag flying over Fort Johnson in the autumn of 1765 and then again in the autumn of 1775, Drayton noted that it was “as if the crescent indicated increasing good fortune, to the American cause.”[13]

It is lamentable that neither William Moultrie nor any of his contemporaries articulated their understanding of the crescent’s symbolic meaning. Perhaps the educated men and women of South Carolina, imbued with a better understanding of English heraldic traditions than later generations, pointed to the new flag flying over the forts in Charleston harbor and understood immediately its symbolism. More in touch with the seasonal cycles of agriculture than twenty-first century spectators, they might have recognized the sickle-shaped crescent as an ancient reference to the harvest moon and its traditional message of hope for an abundant future. In John Drayton’s 1821 publication of his father’s memoirs, the son included a footnote that suggests such an understanding. Reflecting on the coincidence of a crescent flag flying over Fort Johnson in the autumn of 1765 and then again in the autumn of 1775, Drayton noted that it was “as if the crescent indicated increasing good fortune, to the American cause.”[13]

The Addition of the Palmetto Tree in 1776

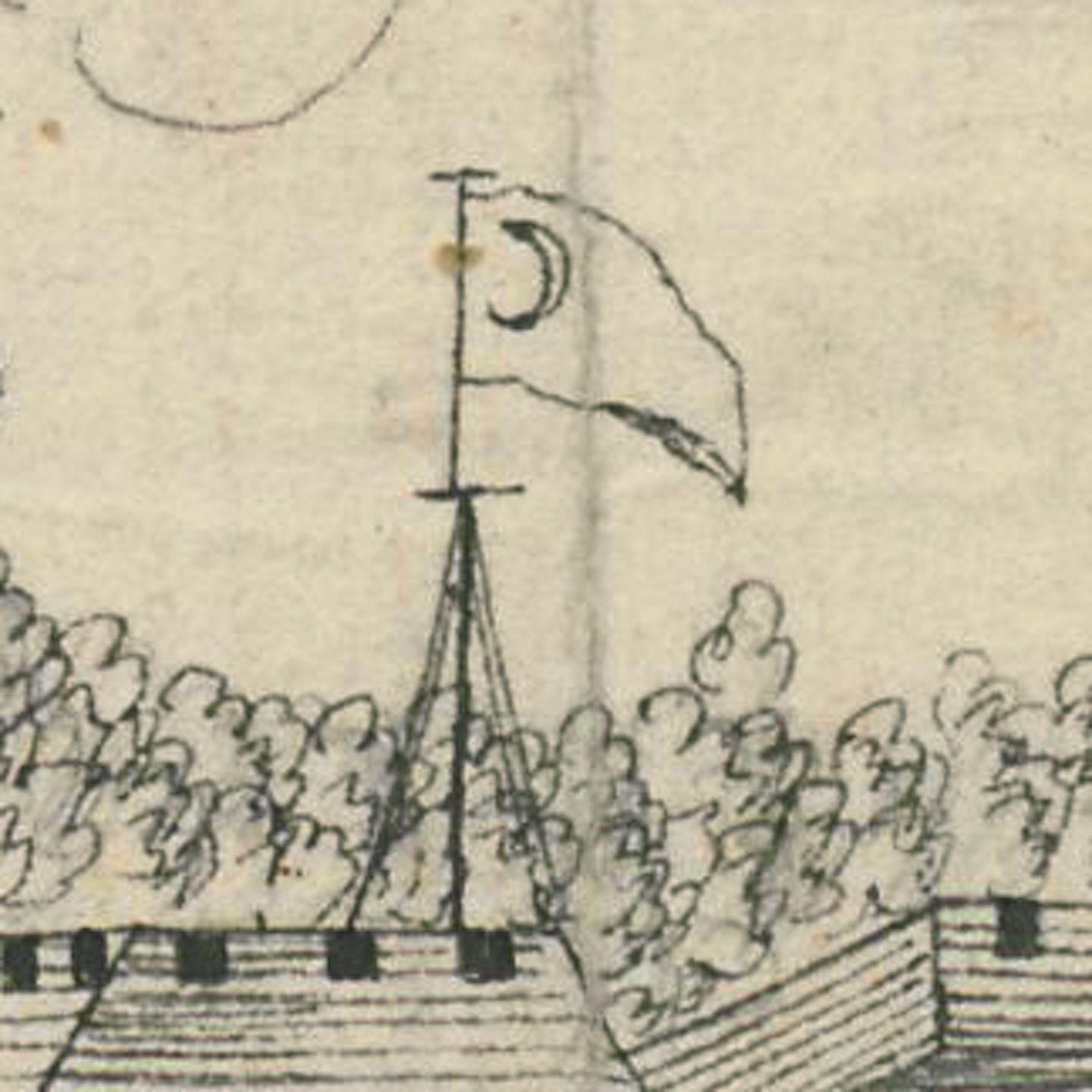

Copies of South Carolina’s new provincial flag followed Colonel William Moultrie from Fort Johnson in 1775 to the unfinished palmetto-log fort constructed on Sullivan’s Island in the spring of 1776. It flew proudly above the fort’s spongy ramparts during the ferocious battle of June 28th, when a squadron of the British Navy under the command of Sir Peter Parker failed to batter their way into Charleston harbor.[14] Two days after their humiliating failure, a British artillery officer named Thomas James completed a sketch of the resilient American fort and its novel flag, and presented his work to Commodore Parker. Parker forwarded the sketch to his superiors in London, and a copy was engraved for publication that August. The flag in William Faden’s engraving, which you can see on the website of the Boston Public Library, is rather too small to see clearly, but the crescent flag is clearly visible in Colonel James’s original sketch, which survives in the collections of the National Archive in suburban London.[15]

Thomas James’ illustration of the South Carolina flag, made on June 30th, 1776, clearly depicts a plain, rectangular banner, although he did not indicate its color. Near the flagstaff appears a proportionately large increscent—that is, a crescent tiled on its side so the horns point to the viewer’s left. Although this sketch is the earliest known depiction of South Carolina’s state flag, we cannot necessarily regard it as completely accurate. Colonel James viewed the flag from a distance, probably through a spyglass, and observed it from the deck of a moving ship during the course of a smoke-filled battle, and departed from the scene a few days later. He might have drawn it precisely as he saw it—as a normal increscent that he might have seen in traditional heraldry. Perhaps coincidentally, perhaps not, a similar increscent appears on a paper note for ten shillings in South Carolina currency that the nascent state government printed in April 1778. That valuable artifact (also held by the University of Notre Dame) includes both an image of a palmetto tree (with Fort Moultrie in the background) and an left-tilted increscent surrounded by florid ornamentation.[16]

Thomas James’ illustration of the South Carolina flag, made on June 30th, 1776, clearly depicts a plain, rectangular banner, although he did not indicate its color. Near the flagstaff appears a proportionately large increscent—that is, a crescent tiled on its side so the horns point to the viewer’s left. Although this sketch is the earliest known depiction of South Carolina’s state flag, we cannot necessarily regard it as completely accurate. Colonel James viewed the flag from a distance, probably through a spyglass, and observed it from the deck of a moving ship during the course of a smoke-filled battle, and departed from the scene a few days later. He might have drawn it precisely as he saw it—as a normal increscent that he might have seen in traditional heraldry. Perhaps coincidentally, perhaps not, a similar increscent appears on a paper note for ten shillings in South Carolina currency that the nascent state government printed in April 1778. That valuable artifact (also held by the University of Notre Dame) includes both an image of a palmetto tree (with Fort Moultrie in the background) and an left-tilted increscent surrounded by florid ornamentation.[16]

In contrast to the increscents depicted by Thomas James in 1776 and the ten-shilling note of 1778, South Carolinians of the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century remembered the original state flag as a plain blue banner with a upward-tilting crescent. Visual representations of this device from the years following the American Revolution are now scarce, but veterans of the war apparently informed their children and grandchildren of the crescent’s correct orientation, and the Palmetto Society paraded the famous flag every summer from 1777 onward. South Carolina lawyer and artist John Blake White (1781–1859), for example, was one of many men who passed along valuable stories of the Revolution that might otherwise have been lost. White’s 1826 painting of the Battle of Sullivan's Island, created to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the event, depicts Sergeant William Jasper raising the provincial flag above the palmetto-log fort. A close inspection of the painting, which now hangs in the halls of the United States Senate, reveals an upturned white crescent, in which we might discern a series of letters spelling the word “Liberty.”

The State Flag of South Carolina

In the aftermath of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island in 1776, South Carolinians apparently began a tradition of adding an image of an upright palmetto tree in the center of blue field of the state’s unofficial flag. Few representations of this “palmetto flag,” as it became known, have survived from the first half of the nineteenth century, but the numerous references to it found in surviving newspapers suggest that it was a common design. In contrast to the elusive crescent, the symbolism of the palmetto tree is rather obvious. The resilient trunk of the humble and ubiquitous palmetto contributed to the American success on the 28th of June 1776, and the tree merited a place of honor on the state’s traditional but unofficial heraldic banner.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island in 1776, South Carolinians apparently began a tradition of adding an image of an upright palmetto tree in the center of blue field of the state’s unofficial flag. Few representations of this “palmetto flag,” as it became known, have survived from the first half of the nineteenth century, but the numerous references to it found in surviving newspapers suggest that it was a common design. In contrast to the elusive crescent, the symbolism of the palmetto tree is rather obvious. The resilient trunk of the humble and ubiquitous palmetto contributed to the American success on the 28th of June 1776, and the tree merited a place of honor on the state’s traditional but unofficial heraldic banner.

As state archivist Wylma Wates noted in her 1985 essay about the history of the state banner, interest in South Carolina’s palmetto flag surged in the early 1830s, during a period of intense political debate over the right of individual states to reject or nullify Federal laws. The blue flag created by William Moultrie in 1775 and its iconic palmetto tree entered the visual vocabulary of men and women beyond the Palmetto State during the second quarter of the nineteenth century, but it remained an unofficial banner.

After South Carolina formally seceded from the Federal Union in December 1860, however, the government of this small, independent nation recognized the need for an official flag. Legislators meeting in Columbia debated various color schemes in January 1861, but everyone participating in the conversation agreed on its basic design. Moultrie’s blue field with a white crescent in the dexter canton remained intact (although the intended orientation of the crescent is somewhat ambiguous), and the added palmetto occupied the place of honor in the center of the field. On January 28th, 1861, after considering many colorful options, the South Carolina General Assembly officially adopted the following design: “Resolved, that from and after the adoption of these resolutions[,] a national flag, or ensign, of South Carolina shall be blue, with a white palmetto upright in the centre thereof, and a white increscent in the upper flag staff corner of the flag.”[17]

Note that the resolution of January 1861 specified the use of an “increscent” rather than a “crescent” in the official design of the state flag. Our knowledge of heraldic traditions informs of the difference between these two terms, but it remains unclear whether the legislators acting in 1861 intended the horns of the state crescent to point upwards or to be rotated ninety degrees as a traditional increscent. Both the direction of the horns and the meaning they implied were clarified a few weeks later by General James Simons in Charleston. Speaking at an event held to commemorate George Washington’s birthday on February 22nd, General Simons congratulated the Washington Light Infantry on the receipt of a new silk banner made by a young lady of distinction. His speech, published in the local newspaper on the day following, provided a valuable description of the colors and qualities of the new flag. “In the upper corner, near the flag-staff,” said Simons, “the increscent joyously turns her horns to heaven, gratefully to receive her promised bounties.[18]

Note that the resolution of January 1861 specified the use of an “increscent” rather than a “crescent” in the official design of the state flag. Our knowledge of heraldic traditions informs of the difference between these two terms, but it remains unclear whether the legislators acting in 1861 intended the horns of the state crescent to point upwards or to be rotated ninety degrees as a traditional increscent. Both the direction of the horns and the meaning they implied were clarified a few weeks later by General James Simons in Charleston. Speaking at an event held to commemorate George Washington’s birthday on February 22nd, General Simons congratulated the Washington Light Infantry on the receipt of a new silk banner made by a young lady of distinction. His speech, published in the local newspaper on the day following, provided a valuable description of the colors and qualities of the new flag. “In the upper corner, near the flag-staff,” said Simons, “the increscent joyously turns her horns to heaven, gratefully to receive her promised bounties.[18]

Revisiting the Flag Design in the Twentieth Century

Considering the text of the 1861 legislative resolution, the 1861 speech of James Simons, and various visual depictions of the state flag created during and after the American Civil War, it would appear that many South Carolinians alive during the second half of the nineteenth century were not familiar with the traditional distinction between the Latin heraldic terms “crescent” and “increscent.” Few people paid any attention to this small detail, however, as the flag’s design was rooted in public memory that extended back more than a century. The matter was of no real consequence until the early years of the twentieth century, when a patriotic effort to promote state flag education once again scrutinized its design.

In the summer of 1909, Governor Martin Frederick Ansel (1850–1945; served 1907–11) initiated a state-wide campaign to raise awareness of South Carolina’s state flag. The governor and his staff were preparing for two high-profile events on the horizon—the presentation of a silver service to the battleship, USS South Carolina, and the unveiling of a Calhoun statue at the U.S. Capitol—and needed a handsome silk flag to display at these state-sponsored events. Ansel, the son of German immigrants, consulted with Alexander Salley (1871–1961), the secretary of the South Carolina Historical Commission (now the S.C. Department of Archives and History). Both men learned that state flags were rare and rather expensive because they had to be made to order. Furthermore, Ansel discovered that few schoolchildren in South Carolina could recognize the state’s flag. The state of North Carolina had recently passed an act to promote flag education, and the governor of her southern neighbor wanted to follow her example. While Martin Ansel campaigned to increase the production and distribution of flags around the Palmetto State, Mr. Salley studied its history to confirm the flag’s proper proportions, design, and colors.[19]

The flag campaign of 1909 inspired two developments of lasting duration. The first legacy of Governor Ansel’s promotional effort was the creation of a law mandating the flag’s presence across South Carolina. In “An Act to Provide for the Display of the State Flag over Public Buildings," ratified on 26 February 1910, the state legislature directed “that the state flag shall be displayed daily, except in rainy weather, from a staff upon the State House and every Court House, one building of the State University and of each State colleges, and upon every public school building, except when the school is closed during vacation.”[20] The second legacy of the 1909 campaign was far more subtle, but graphically important. Governor Ansel charged Alexander Salley with the duty of verifying the proper design and colors of the state flag. The design he endorsed for official use, and which remains in use today, includes a crescent tilted approximately forty-five degrees to the left of vertical. To my knowledge, Salley did not articulate a reason for this modification, but I have a theory of its origin.

In the course of his historical research in 1909, Alexander Salley reviewed much of the same body of evidence that I’ve summarized in this essay, including the design resolution adopted in January 1861. As an erudite and fastidious researcher who was criticized on occasion for being a bit short-sighted, I suspect Salley may have become fixated on a contradiction embedded within state’s vexillological tradition. Having been raised in South Carolina in the aftermath of the Civil War, he was familiar with the blue palmetto flag with its upturned white crescent in the dexter corner. The resolution adopted by the state legislature in 1861 specified the use of an “increscent,” however, and the precise meaning of that ancient term might have troubled Mr. Salley. The official design of 1861 called for a crescent rotated ninety degrees to the left, its horns pointing towards the hoist or flagstaff, while the state flags displayed in Salley’s lifetime consistently included an upturned crescent with its horns pointing skyward. I suspect, but currently have no proof, that Alexander Salley resolved this graphical conundrum by splitting the difference. By rotating the crescent forty-five degrees to the left of vertical, Salley skewed slightly the traditional orientation and nearly delivered the “increscent” specified by the legislature in 1861.[21]

The State Flag of the Future

By the turn of the twentieth-first century, the state flag of South Carolina had advanced from an obscure provincial banner to one of the most (if not the most) recognizable flags in the United States. The familiar blue flag can be found in every public building and school across the Palmetto State, and it’s now fairly easy to purchase reproductions of varying qualities. Inconsistencies in color, shape, and other graphical details persist, however, so in 2018 the state legislature appointed a committee to study the flag’s design history and make recommendations. The committee studied the evolution of the state flag from 1775 through the twentieth century, but focused solely on the design, including its color, the shape of the palmetto, and the orientation of the crescent. You can read their conclusions by visiting the website of the South Carolina State Legislature.

I believe the South Carolina State Flag Study Committee did an excellent job of determining the proper shade of blue for the flag’s principal field. Drawing on the expertise of others, the committee selected a very specific hue that reflects both the state’s British roots and the legacy of local indigo production in the eighteenth century (see Episode No. 124 for more information on that topic). The study group also decided to retain Alexander Salley’s tilted crescent, although they did not explore the contrasting definitions of the terms “crescent” and “increscent.” Since the publication of the committee’s initial report in March 2020, many South Carolinians have expressed displeasure with the appearance of the palmetto tree in their recommend design. In response, the committee published an addendum in January 2021 offering two additional design options. The public has largely criticized these designs as well, and I suspect we’ll be hearing more about modifications to the state flag in the coming months.[22]

I believe the South Carolina State Flag Study Committee did an excellent job of determining the proper shade of blue for the flag’s principal field. Drawing on the expertise of others, the committee selected a very specific hue that reflects both the state’s British roots and the legacy of local indigo production in the eighteenth century (see Episode No. 124 for more information on that topic). The study group also decided to retain Alexander Salley’s tilted crescent, although they did not explore the contrasting definitions of the terms “crescent” and “increscent.” Since the publication of the committee’s initial report in March 2020, many South Carolinians have expressed displeasure with the appearance of the palmetto tree in their recommend design. In response, the committee published an addendum in January 2021 offering two additional design options. The public has largely criticized these designs as well, and I suspect we’ll be hearing more about modifications to the state flag in the coming months.[22]

My purpose in reviewing three centuries of flag history in South Carolina was not to upstage the very capable State Flag Study Committee, chaired by my old friend Dr. Eric Emerson, but simply to provide additional context for the symbols that we now take for granted on that familiar banner. The use of a blue field in the South Carolina flag in 1775 was not a self-conscious expression of the state’s indigo culture, but simply the continuation of a long-standing tradition of flying British ensigns in Charleston harbor. The Union Jack placed in the dexter canton of the “old common blue fort flagg” was replaced by a single white crescent to represent the modest hope for a brighter future. The upright palmetto tree added unofficially in 1776 embodies the spirit of resilience that empowers all South Carolinians to persevere in the face of adversity. In short, I believe this distinctive state flag delivers a fitting message to all who view it and visit the Palmetto State. These silent symbols echo the Latin text of the state’s official motto, adopted more than two centuries ago: Dum spiro spero (“While I breathe, I hope”).

[1] Mark Anthony Porny, The Elements of Heraldry (London: F. Newbery, 1765; first edition), unnumbered page in the alphabetical dictionary at the end of the book.

[2] The published literature of English heraldic history is vast. Besides the abovementioned 1765 book by Porny (and his 1771 edition of the same title), I would recommend Charles Boutell and A. C. Fox-Davies, The Handbook to English Heraldry (11th edition; London: Reeves & Turner, 1914), which is also available online.

[3] For more information about the Union flag, see W. G. Perrin, British Flags: Their Early History, and their Development at Sea; with an account of the origin of the flag as a Nation Device (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1922), 54–73. This book is available online at Project Gutenburg.

[4] Both red and blue ensigns can be seen in Bishop Roberts’s painting, which is viewable on the website of Colonial Williamsburg.

[5] Fitzhugh McMaster, in Soldiers and Uniforms: South Carolina Military Affairs, 1670–1775 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1971), 43–46, stated that the uniform of the South Carolina provincial regiment created in 1760 included a crescent on their caps. This theory is not supported by any known contemporary documents, and seems to be based on the belief that the personal seal of Lieutenant Governor William Bull (which included a crescent to indicate cadence) was used on the commissions of the officers of this regiment, since King George II had died and his royal seal was set aside until a new one arrived in Charleston. The chronology of McMaster’s theory does not conform to the facts, however. The South Carolina legislature ratified an act on 20 August 1760 to raise a new regiment of provincial troops. Lt. Gov. Bull commissioned Thomas Middleton to serve as colonel of this regiment on 16 September, and issued commissions for the remaining officers in the following days. King George II died on 25 October, but news of his death did not arrive in Charleston until January, 1761. By that time, the officers and early recruits of the new provincial regiment were already in uniform and marching westward towards the Cherokee territory, recruiting more men as they proceeded.

[6] John Drayton, Memoirs of the American Revolution, volume 1 (Charleston, S.C.: A. E. Miller, 1821), 45.

[7] It is possible that Captain Robert Fanshaw of HMS Speedwell, then stationed in Charleston, reported to the British Admiralty some information about the crescent flag and his interaction with the “volunteers” who infiltrated Fort Johnson in October 1765. My efforts to pursue this line of enquiry within the surviving Admiralty records, held at the National Archives at Kew, has been thwarted by the current Covid pandemic, but I plan to investigate Captain Fanshaw’s records later in 2021. Stay tuned for a future podcast on that topic.

[8] South Carolina Gazette, 17 May 1773. An earlier militia company of light infantry, commanded by Captain Thomas Savage, was in existence in Charleston by the early months of 1766; see the local news report in the South Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, 6 May 1766. Perhaps the “volunteers” who raided Fort Johnson in October 1765 with a crescent flag afterwards organized themselves into a company of light infantry. Lt. Gov. Bull reviewed the eight companies of the Charles Town regiment in South Carolina Gazette, 7 June 1773.

[9] William Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, So Far As It Related to the States of North and South-Carolina, and Georgia, volume 1 (New York: David Longworth, 1802), 90–91. Members of the 2nd Regiment began removing from Fort Johnson to Charleston in early November 1775, so Moultrie’s creation of the flag must have occurred between late September and early November 1775.

[10] The 1775 note in question is part of the colonial currency collection held by the Department of Special Collections at the University of Notre Dame, and is viewable online at https://coins.nd.edu/ColCurrency/CurrencyText/SC-11-15-75.html (accessed on 28 January 2021).

[11] South Carolina Historical Society, Collections of the South Carolina Historical Society, volume 3 (Charleston: By the society, 1859), 205, 225–26.

[12] See the General Orders for 9 March 1776 in Barnard Elliott, “4th South Carolina Regiment order book, 1775–1778,” South Carolina Historical Society, 34-0205. An imperfect transcription of Elliott’s “diary” was published in the Charleston Year Book of 1889, pages 151–262, but the original text has been digitized and is now available through the Lowcountry Digital Library.

[13] Drayton, Memoirs of the American Revolution, volume 2, page 53, footnote.

[14] A wealth of literature has been published about the 1776 Battle of Sullivan’s Island. See, for example, my podcast Episode No. 18, Episode No. 71; and Episode No. 117.

[15] National Archives of the United Kingdom, MPI 1/99, extracted from a letter dated 9 July 1776 from Sir Peter Parker (held in ADM 1/486).

[16] The 1778 note in question is part of the colonial currency collection held by the Department of Special Collections at the University of Notre Dame, and is viewable online at https://coins.nd.edu/ColCurrency/CurrencyText/SC-04-10-78.html (accessed on 28 January 2021).

[17] Wylma Anne Wates, “‘A Flag Worthy of Your State and People’: The South Carolina State Flag,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 86 (October 1985): 326–29; Charleston News and Courier, 18 November 1909, page 9, “South Carolina Flag. What the State Legislature of 1861 Intended for Design.”

[18] Charleston Daily Courier, 23 February 1861, page 1, “Washington’s Birthday.”

[19] Numerous newspaper articles published in the summer and autumn of 1909 document the growth of Governor Ansel’s flag campaign. See, for example, [Columbia, S.C.] The State, 20 July 1909, page 10, “Governor Buys A State Flag”; Charleston News and Courier, 9 November 1909, page 2, “Columbia News and Gossip. Significance of the Crescent On State Flag Explained”; The State, 5 December 1909, page 17, “The State Flag—Its History.”

[20] State of South Carolina, Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina Passed during the Regular Session of 1910 (Columbia, S.C.: Gonzales and Bryan, 1910), 753.

[21] I have not yet searched for evidence of Salley’s exploration of the meaning of the term “increscent” among his papers at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History (SCDAH), but one can gain insight into his character and working methods in Charles H. Lesser, The Palmetto State’s Memory: A History of the South Carolina Department of Archives & History, 1905–1960 (Columbia: South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 2009), which is available online through the SCDAH website.

[22] See “Report of the South Carolina State Flag Study Committee,” published on 4 March 2020, and “Addendum to the Report of the South Carolina State Flag Study Committee, dated March 4, 2020,” published on 20 January 2021 (https://www.scstatehouse.gov/CommitteeInfo/SCStateFlagStudyCommittee/SCS...), accessed on 28 January 2021.

NEXT: “An Undeniable Possession of Talent”: James Henry Conyers of Charleston

PREVIOUSLY: Street Auctions and Slave Marts in Antebellum Charleston

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments