Captain Thomas Hayward’s Poetic Description of 1769 Charles Town

Processing Request

Processing Request

April is National Poetry Month, a fitting time to explore the history of a well-known poem with a puzzling past. This famously bold verse from 1769 contains a diverse and sarcastic description of Charleston that is preserved in a single manuscript source. The author’s name is imperfectly recorded in that document, however, and his identity has remained obscure. Efforts to interpret clues imbedded in the manuscript have uncovered a new candidate whose unfamiliar name recalls a distant era of local maritime history and provides a colorful backdrop for the creation of the now-famous poem.

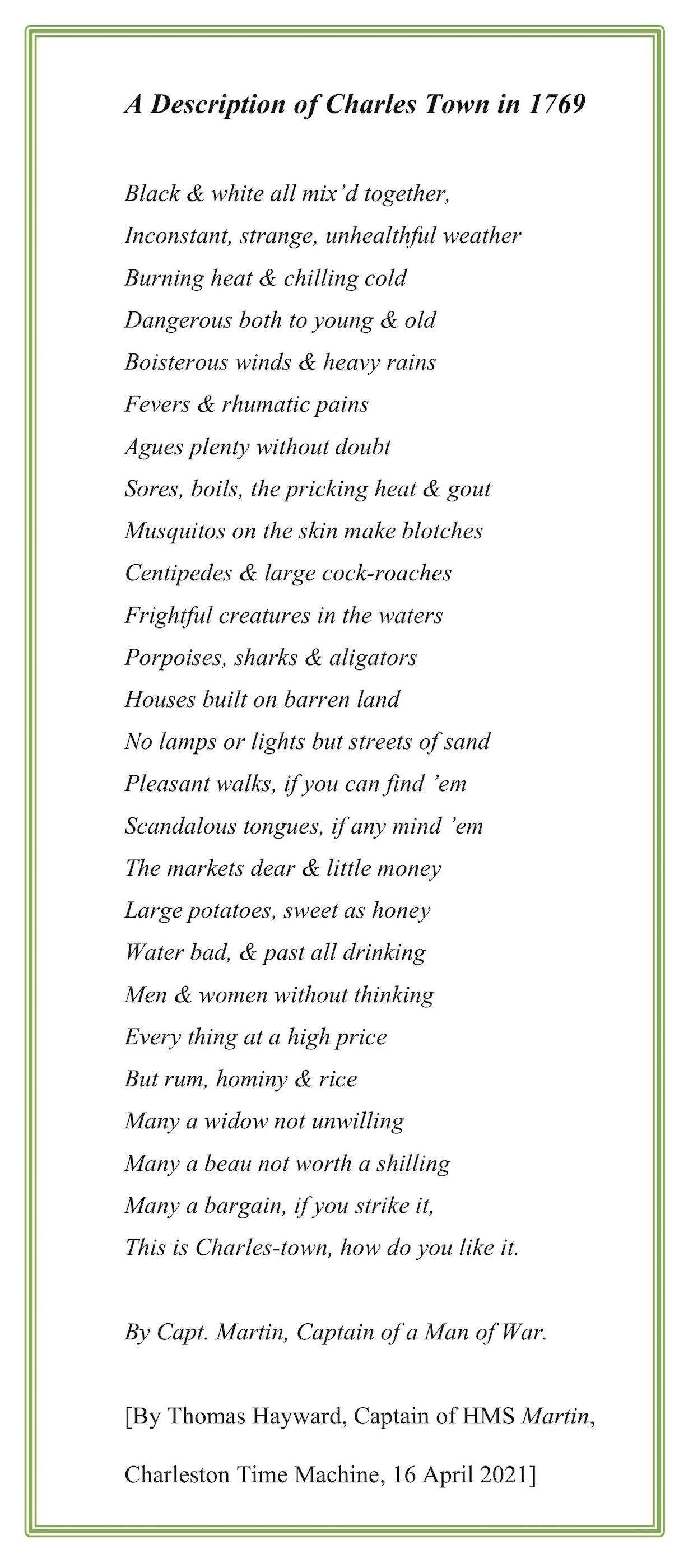

Among the valuable collections held at the South Caroliniana Library at the University of South Carolina is a curious manuscript purchased from a London dealer in 1948. The document in question contains the heading “A Description of Charles Town in 1769,” which is followed by twenty-six lines of poetic verse. The hand-written text forms one continuous column containing thirteen rhyming couplets and covers both sides of a single sheet of paper. At the end of the poem appears a flourish of pen strokes, followed by a phrase that vaguely identifies the author of the poem: “By Capt. Martin, Captain of a Man of War.” This imprecise attribution suggests that the person who created this manuscript copied the text from an earlier source, and was perhaps not personally familiar with the author. Although the title of the poem reflects the colonial-era spelling of Charles Town, which was officially renamed Charleston in August of 1783 (see Episode No. 123), the handwriting, ink, and paper are all sufficiently generic to suggest that this document might have been created sometime during the last quarter of the eighteenth century or the first quarter of the nineteenth century.[1]

This “Description of Charles Town in 1769” has been familiar to scholars and the reading public for more than half a century. The New York Public Library published a flawed transcription of the poem in 1967 as a sort of colonial curiosity, but the editor of that institutional bulletin did not speculate about the identity of the author.[2] A more accurate rendering of the poem appeared in a popular 1977 compilation of primary sources published by the University of South Carolina Press, titled The Colonial South Carolina Scene. In his brief introduction to the “Description of Charles Town in 1769,” the editor did not attempt to identify its author. He simply stated that “nothing is known of the origins of the following piece of verse.”[3]

This “Description of Charles Town in 1769” has been familiar to scholars and the reading public for more than half a century. The New York Public Library published a flawed transcription of the poem in 1967 as a sort of colonial curiosity, but the editor of that institutional bulletin did not speculate about the identity of the author.[2] A more accurate rendering of the poem appeared in a popular 1977 compilation of primary sources published by the University of South Carolina Press, titled The Colonial South Carolina Scene. In his brief introduction to the “Description of Charles Town in 1769,” the editor did not attempt to identify its author. He simply stated that “nothing is known of the origins of the following piece of verse.”[3]

Over the past four decades, the text of this late-colonial “Description of Charles Town” has been quoted in a number of books, articles, and blogs about the Palmetto City and the early history of South Carolina in general. Its popularity no doubt stems from the poem’s brisk, modern cadence and straightforward language that provides a vibrant snapshot of life in the colonial capital. The author succeeded in painting a colorful picture of Charleston within a compact frame, making reference to such diverse topics as the climate, wildlife, health, foodways, social life, demographics, commerce, and infrastructure. After enumerating the town’s faults and follies, the poem pivots to the reader and boldly asks his or her opinion of this imperfect colonial outpost. In short, this 1769 “Description of Charles Town” is an engaging piece of verse that continues to please readers and auditors more than two and a half centuries after its creation.

The brash honesty of the poem’s descriptive language, tinged with a bit of satirical wit, suggests that the author must have been a keen observer of his surroundings and a jovial companion at the dinner table. These characteristics inspired me to learn more about the author in order to understand his perspective within the highly stratified society he lampooned. What sort of social station did he occupy in 1769, and what experiences shaped his impression of Charleston? The first step in this inquiry, of course, was to review the existing body of scholarship on this topic. Looking at a variety of publications that have quoted from this popular “Description” in recent decades, I noticed that some writers have simply sidestepped the question of author’s identity, while others have followed the cue at the end of the manuscript and stated that the poem was written by one “Captain Martin.”[4]

Only one recent source has ventured to propose a specific individual as the author of the “Description.” The 2015 edition of The Cambridge History of American Poetry identifies the author as one Alexander Martin (1740–1807), a native of New Jersey and Princeton graduate who moved to Salisbury, North Carolina in the early 1760s. There he worked as a merchant and later as an attorney in the decade preceding the American Revolution. During and after the War of Independence, Martin wrote some patriotic poetry that was published in various American newspapers, but he is best remembered as a unsuccessful infantry officer and as a post-war governor of the Tar Heel State. It appears, therefore, that the editors of the Cambridge History of American Poetry attributed the poem to Alexander Martin on the basis of three criteria—his surname matched that given in the manuscript source, he lived in one of the Carolinas at the time the poem was written, and he wrote some poetry during his lifetime. In my opinion, however, these generic facts are not sufficient to justify the attribution to Alexander Martin.[5]

Although Governor Martin was known to have dabbled in poetic verse while living in the piedmont region of North Carolina, I can find no evidence connecting him to the port town of Charleston, South Carolina, some two hundred miles distant. Furthermore, the manuscript in question clearly identifies the author of the “Description of Charles Town in 1769” as the “captain of a man of war”—that is, a warship. The only warships in Charleston before 1776 were vessels belonging to the British Navy. A search through the voluminous records of the British Navy, held at the National Archives at Kew, produced no references to Alexander Martin of New Jersey and North Carolina, who never served in the Royal Navy and was never the captain of a British warship in 1769 or any other time. In my opinion, these facts disqualify Alexander Martin as a potential author of the “Description of Charles Town in 1769.”[6]

Although Governor Martin was known to have dabbled in poetic verse while living in the piedmont region of North Carolina, I can find no evidence connecting him to the port town of Charleston, South Carolina, some two hundred miles distant. Furthermore, the manuscript in question clearly identifies the author of the “Description of Charles Town in 1769” as the “captain of a man of war”—that is, a warship. The only warships in Charleston before 1776 were vessels belonging to the British Navy. A search through the voluminous records of the British Navy, held at the National Archives at Kew, produced no references to Alexander Martin of New Jersey and North Carolina, who never served in the Royal Navy and was never the captain of a British warship in 1769 or any other time. In my opinion, these facts disqualify Alexander Martin as a potential author of the “Description of Charles Town in 1769.”[6]

Having dismissed Alexander Martin as a viable candidate, we return to the sole clue to the author’s identity that appears within the poem’s manuscript source. The final line in the document attributes the poem to “Capt. Martin, Captain of a Man of War.” To my mind, that phrase inspires a rather obvious question: Was there a Captain Martin who came to colonial-era Charleston in command of a British man-of-war? As I mentioned in Episode No. 148, scores of British warships called at the port of Charleston during the city’s colonial era, and dozens were stationed here temporarily between 1720 and 1775. During that long era, the only warship that came to Charleston with a captain named Martin was His Majesty’s Ship Blandford, a sixth-rate, twenty-gun frigate commanded by William Martin (ca. 1696–1756). Captain Martin and the Blandford were present here between June 1721 and September 1724, and William later rose through the ranks to become an admiral before his death in 1756. Having expired thirteen years before the creation of this poetic puzzle, this William Martin could not have been the author of the “Description of Charles Town in 1769.”[7]

Failing to identify a “Capt. Martin” who came to South Carolina in 1769 aboard a man-of-war, we can revise our inquiry to focus on the chronology rather than the surname: What British warships sailed to Charleston during the year in question, and might we identify a potential author within that subset of naval officers? Both the extant navy records and Charleston newspapers of that era indicate that six British warships anchored in Charleston harbor for various periods of time during the year 1769. These vessels and their commanders included His Majesty’s Ships Fowey (Captain Mark Robinson), Bonetta (Capt. James Wallace), Viper (Capt. Robert Linzee), Tryall (Capt. William Phillips), St. Lawrence (Lieut. Ralph Dundas), and Martin (Captain Thomas Hayward).

The presence of a British warship in Charleston harbor in 1769 bearing the name mentioned in final line of the poetic “Description” led me to consider a new solution to this old puzzle: Is it possible that the name “Martin” in the manuscript does not indicate the surname of the author, but rather the name of the warship under his command? The imprecise and syntactically awkward attribution in the manuscript appears to support such a theory. Whoever copied the poem from its original source was apparently unfamiliar with the captain and the name of his ship. As a result, the copyist appears to have garbled the text of the original attribution. I propose that if we rearrange a few words in the final line of the extant manuscript and remove one repeated word, we can conclude that the “Description of Charles Town in 1769” was not composed “by Capt. Martin, Captain of a Man of War,” but rather “by the captain of the Martin, a man-of-war.”

The presence of a British warship in Charleston harbor in 1769 bearing the name mentioned in final line of the poetic “Description” led me to consider a new solution to this old puzzle: Is it possible that the name “Martin” in the manuscript does not indicate the surname of the author, but rather the name of the warship under his command? The imprecise and syntactically awkward attribution in the manuscript appears to support such a theory. Whoever copied the poem from its original source was apparently unfamiliar with the captain and the name of his ship. As a result, the copyist appears to have garbled the text of the original attribution. I propose that if we rearrange a few words in the final line of the extant manuscript and remove one repeated word, we can conclude that the “Description of Charles Town in 1769” was not composed “by Capt. Martin, Captain of a Man of War,” but rather “by the captain of the Martin, a man-of-war.”

HMS Martin was a fourteen-gun, ship-rigged, unrated sloop-of-war, which is nautical jargon for a diminutive three-masted vessel at the lower end of the spectrum of size and firepower within the Royal Navy. This Martin, the fourth British naval vessel to bear the name, was launched in London in 1761 and sold out of service in 1784. Although many readers are familiar with larger warships from the age of sail that bore intimidating names, the Martin belonged to a smaller class of eighteenth-century British vessels that usually performed coastal patrol duty and were identified by a variety of avian names, including the Vulture, Swift, Falcon, Swan, Kingfisher, Swallow, Raven, Pelican, and so on.[8]

The captain of HMS Martin during the period in question was one Thomas Hayward (ca. 1736–1775), a native of Exeter in Devonshire who was approximately thirty-three years of age in 1769. Like other naval officers of his time, Hayward entered the British Navy as a teenage midshipman and passed the lieutenant’s examination in the spring of 1756. His first command was HMS Spy, a ten-gun sloop-of-war, to which he was assigned in November 1761. After more than a year of patrolling the southeast coast of England during the later stages of the Seven-Years War, Captain Hayward transferred in the spring of 1763 to HMS Senegal, a fourteen-gun sloop-of-war that was assigned to patrol the Gulf of St. Lawrence in eastern Canada. He returned to England in early February 1767 and was allowed a few months rest. That June, the British Admiralty commissioned Captain Hayward to outfit the fourteen-gun HMS Martin for service along the coastline of North Carolina.[9]

Instead of proceeding directly to his assigned station, Captain Hayward sailed the Martin from England to Madeira to Charleston, where he arrived in late November 1767. The capital of colonial South Carolina was nearly a century old at that time and hosted a more vibrant and cosmopolitan social scene than any community in contemporary North Carolina. Captain Hayward no doubt wanted to sample the town’s hospitality before taking up his post, but duty also compelled him to linger briefly in Charleston. The town’s naval facilities were more mature than those in the northern colony, and the Martin would need to visit Charleston periodically for supplies and maintenance in addition to social recreation. After two weeks of shore leave, Captain Hayward and his crew weighed anchor on December 9th and the Martin proceeded to her new base in Wilmington, North Carolina.[10]

Over the next four years, Captain Hayward and the Martin returned to Charleston on seven different occasions. He was here for nearly three weeks during the month of May 1768, for example, during which time he probably engaged in conversations about the tense political situation then unfolding in Boston. The British Parliament had, during the previous summer, ratified a series of laws proposed by Chancellor Charles Townshend that were designed to extract more revenue from the American colonies. New import duties went into effect on January 1st, 1768, and the people of Boston had organized a non-importation agreement to protest the enforcement of the so-called “Townshend Acts.” Other colonies were following suit, and the British government was determined to make an example of Boston by enforcing compliance through intimidation.[11]

Captain Hayward and the Martin returned to Wilmington in late May 1768. Shortly thereafter, he received an urgent communication from General Thomas Gage, the commander-in-chief of all British troops in North America. Gage planned to move two regiments of British regulars from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to Boston, Massachusetts, and had summoned Royal Navy vessels posted along the Atlantic coast to facilitate the move. The Martin arrived at Halifax that August and joined a small fleet that included His Majesty’s Ships Mermaid, Romney, Launceston, Glasgow, Beaver, Senegal, Bonetta, Hope, St. John, Lawrence, Magdalene, and several smaller vessels.

Captain Hayward and the Martin returned to Wilmington in late May 1768. Shortly thereafter, he received an urgent communication from General Thomas Gage, the commander-in-chief of all British troops in North America. Gage planned to move two regiments of British regulars from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to Boston, Massachusetts, and had summoned Royal Navy vessels posted along the Atlantic coast to facilitate the move. The Martin arrived at Halifax that August and joined a small fleet that included His Majesty’s Ships Mermaid, Romney, Launceston, Glasgow, Beaver, Senegal, Bonetta, Hope, St. John, Lawrence, Magdalene, and several smaller vessels.

In early September, more than two regiments of red-coated soldiers, accompanied by a small train of artillery, were distributed among the Navy vessels riding in Halifax Harbor. The convoy then proceeded to Boston Harbor, where they anchored around the northeast part of the town on the last day of the month. On the first of October, nearly two thousand soldiers disembarked from the Martin and the other ships into longboats that ferried them to the town’s Long Wharf. Local silversmith Paul Revere immediately published an engraved image of the scene, which provides a valuable contemporary illustration of HMS Martin and her companion vessels. The military intervention at Boston in the autumn of 1768, intended to suppress colonial dissent, sparked further protests that led to the Boston Massacre and ultimately to a war for the independence of a new nation.[12]

Captain Hayward did not linger in Massachusetts after completing his assignment. The Martin returned to Halifax later in October, then sailed in November for North Carolina and arrived at Wilmington by the end of December.[13] After some weeks ashore, the captain assembled his crew in early 1769 and proceeded into the Atlantic for a cruise along the Carolina coastline. The Martin returned to Charleston on April 4th and remained at anchor in the harbor until May 10th. On that day, Captain Hayward sailed back to Wilmington, but then immediately returned to Charleston for reasons unknown. After spending a few additional days here in late May, the Martin continued onward to Port Royal Harbor.[14]

The now-famous “Description of Charles Town in 1769” must have been written during Captain Hayward’s five-and-a-half-week spring sojourn. No details of his movements or associations during that era survive, but he must have enjoyed a variety of social opportunities. As an officer of the king visiting the capital of a colonial province, he likely mingled with Charleston’s elite and received invitations to private dinners, dancing assemblies, and club meetings of local gentlemen. He also spent some hours engaged in polite conversation with eligible young ladies whose names are now forgotten. Taking cues from his poetic “Description,” we can imagine the captain conversing with his hosts about the “pricking heat,” the undrinkable water, and the low price of hominy and rice. “Pleasant walks” under the moonlight with local belles were rendered less enjoyable by the unlit sandy streets filled with cockroaches and mosquitos. “Scandalous” gossip about willing widows and foppish beaux formed a sharp contrast with the harsh realities of urban slavery, in which persons of European and African descent spent their short lives “all mix’d together.” Captain Hayward, we now know, observed and digested these varied scenes through many a glass of cheap rum and asked his companions how they liked it.

The now-famous “Description of Charles Town in 1769” must have been written during Captain Hayward’s five-and-a-half-week spring sojourn. No details of his movements or associations during that era survive, but he must have enjoyed a variety of social opportunities. As an officer of the king visiting the capital of a colonial province, he likely mingled with Charleston’s elite and received invitations to private dinners, dancing assemblies, and club meetings of local gentlemen. He also spent some hours engaged in polite conversation with eligible young ladies whose names are now forgotten. Taking cues from his poetic “Description,” we can imagine the captain conversing with his hosts about the “pricking heat,” the undrinkable water, and the low price of hominy and rice. “Pleasant walks” under the moonlight with local belles were rendered less enjoyable by the unlit sandy streets filled with cockroaches and mosquitos. “Scandalous” gossip about willing widows and foppish beaux formed a sharp contrast with the harsh realities of urban slavery, in which persons of European and African descent spent their short lives “all mix’d together.” Captain Hayward, we now know, observed and digested these varied scenes through many a glass of cheap rum and asked his companions how they liked it.

The Martin did not again return to Charleston until March 18th, 1770, at which time Captain Hayward planned to stay for a few weeks as usual. News soon arrived, however, that Governor William Tryon of North Carolina was planning to visit the capital of his southern neighbor, and might require a berth on the Martin to carry him home later in April or May. Captain Hayward obligingly cooled his heels in Charleston for several additional weeks that spring, and used the time to nurture personal relationships sparked during previous visits. The town’s social life was enlivened on April 20th by the arrival of Governor Tryon and his wife, Margaret, who had traveled over land in a private coach from Brunswick to Charleston. Mrs. Tryon soon tired of the succession of dinner parties and soirees, however, and six days later departed for North Carolina in her carriage.[15]

On the same day as Mrs. Tryon's departure, Thursday, April 26th, 1770, Thomas Hayward went to St. Philip’s Church with his closest companions to exchange wedding vows with a young lady named Anne Sinclair (born ca. 1752). Anne was the daughter of Sarah Cartwright and the late John Sinclair (1720–1755), a Quaker merchant who had been the first librarian of the Charleston Library Society after its founding in 1748.[16] The newlywed couple, accompanied by Governor Tryon, boarded the Martin one week after their wedding and sailed out of Charleston Harbor for Wilmington on May 4th.[17] The Martin sojourned in Halifax for the summer of 1770, but it’s unclear whether or not Mrs. Hayward accompanied her husband. After his brief return to Wilmington in late August, however, Anne probably sailed with the Martin to Charleston for a six-week visit between late September and early November.[18]

The Martin returned to Charleston in late March 1771 for a customary spring sojourn and sailed for Wilmington in early May. Immediately after returning to their home port, Captain Hayward and his crewmen found themselves on the periphery of a violent local drama. Disgruntled colonists on the western piedmont clashed with local government forces on May 16th in what became known as the Battle of Alamance. That event proved to be the end of a long series of armed conflicts in the North Carolina backcountry commonly called the “Regulator Movement,” but many communities feared for their immediate safety. One hundred and fifty miles southeast of the battle, the civic leaders of Wilmington appealed to Captain Hayward for military assistance. He generously offered to distribute muskets and cutlasses from the Martin to citizens if insurgents attacked the town. The threat quickly dissipated, however, and the affair was soon over. Nevertheless, several American newspapers reported that “the inhabitants of Wilmington unanimously voted the thanks of the town to Captain Thomas Heyward [sic], of His Majesty’s Ship Martin, for the readiness he discovered to contribute every thing in his power to the support of government and the laws of the province.”[19]

The Martin returned to Charleston in late March 1771 for a customary spring sojourn and sailed for Wilmington in early May. Immediately after returning to their home port, Captain Hayward and his crewmen found themselves on the periphery of a violent local drama. Disgruntled colonists on the western piedmont clashed with local government forces on May 16th in what became known as the Battle of Alamance. That event proved to be the end of a long series of armed conflicts in the North Carolina backcountry commonly called the “Regulator Movement,” but many communities feared for their immediate safety. One hundred and fifty miles southeast of the battle, the civic leaders of Wilmington appealed to Captain Hayward for military assistance. He generously offered to distribute muskets and cutlasses from the Martin to citizens if insurgents attacked the town. The threat quickly dissipated, however, and the affair was soon over. Nevertheless, several American newspapers reported that “the inhabitants of Wilmington unanimously voted the thanks of the town to Captain Thomas Heyward [sic], of His Majesty’s Ship Martin, for the readiness he discovered to contribute every thing in his power to the support of government and the laws of the province.”[19]

Shortly after the conclusion of the Regulator drama in North Carolina, Captain Hayward received orders from the Admiralty to bring the Martin home. Rather than departing right away and sailing directly to England, however, the Martin embarked on a circuitous journey that might have involved the conveyance of some sensitive government intelligence. Perhaps it was simply a farewell tour of familiar ports. In any case, the Martin departed from Wilmington for the last time in mid-June 1771 and sailed northward for Massachusetts. After a brief respite in Boston Harbor, she continued on to Halifax. The crew of the Martin weighed anchor in mid-September and again paused briefly at Boston before continuing southward to Charleston.

Moored before the capital on October 14th, Captain and Mrs. Hayward bid farewell to friends and family and, no doubt, promised to return to South Carolina at some point in the future. Their final visit was necessarily brief as the Martin’s tour of duty came to an end. With favorable wind and tide on October 19th, the crewmen shipped the anchor and set a course for home. They reached England well before Christmas, but the business of settling accounts, stowing the ship, and discharging the crew kept the captain busy for some further weeks. Thomas Hayward signed his logbook on December 26th, 1771, and delivered it to the Admiralty Office in London, thus ending his four-year association with HMS Martin.[20]

Over the next two and a half years, Captain and Mrs. Hayward enjoyed time together while living in or near Exeter. Thomas remained in good standing with the Royal Navy during this interval ashore and received the customary half-pay due to officers of his rank. It is unclear, however, whether the long duration of this respite arose from bureaucratic generosity or some physical infirmity. He had been in nearly continuous active service since his teenage years and now, in his mid-thirties, perhaps deserved a long spell of shore leave. Alternatively, Thomas Hayward’s health might have been in decline as a result of his naval career. In either case, he made his will on April 13th, 1773, while in possession of sound mind and memory, but cognizant of “the uncertainties of this transitory life.” The brief document assigned Hayward’s modest estate to his young wife, Anne, and appointed a naval agent in London, Edward Ommanney, to be sole executor.[21]

In early June 1774, fourteen months after drafting his last will and testament, Captain Hayward was recalled to active duty. The Admiralty commissioned him to take command of HMS Wolf, an eight-gun sloop-of-war patrolling the Cornish coast of southwest Britain.[22] Anne Hayward, who might have been pregnant at the time, did not follow her husband to sea. She remained ashore in the port town of Penzance, where the Wolf docked periodically and the captain could visit his wife. The couple were together on February 20th, 1775, when they buried an infant named Thomas Hayward in the nearby churchyard of St. Maddern. The child’s age was not recorded, but he might have been a newborn, and his mother might have suffered complications during the delivery. Two months later, the grieving captain returned to the same gravesite on April 28th to bury his wife, Anne Sinclair Hayward, a native of Charleston, aged around twenty three years.

In early June 1774, fourteen months after drafting his last will and testament, Captain Hayward was recalled to active duty. The Admiralty commissioned him to take command of HMS Wolf, an eight-gun sloop-of-war patrolling the Cornish coast of southwest Britain.[22] Anne Hayward, who might have been pregnant at the time, did not follow her husband to sea. She remained ashore in the port town of Penzance, where the Wolf docked periodically and the captain could visit his wife. The couple were together on February 20th, 1775, when they buried an infant named Thomas Hayward in the nearby churchyard of St. Maddern. The child’s age was not recorded, but he might have been a newborn, and his mother might have suffered complications during the delivery. Two months later, the grieving captain returned to the same gravesite on April 28th to bury his wife, Anne Sinclair Hayward, a native of Charleston, aged around twenty three years.

The loss of his young family exacted a toll on Thomas’s mental and physical health, but details of his declining condition are now long lost. We know, however, that he enjoyed the companionship of his subordinate officers aboard the Wolf, who no doubt lamented the captain’s burden of burying his only child and young wife. On both occasions, Captain Hayward was accompanied to the graveside by his second-in-command, Lieutenant Bartholomew James, who kept a private journal of his early career at sea. Lieutenant James, later a Rear Admiral in the Royal Navy, recalled in his diary that he returned to the churchyard of St. Maddern a third time on September 14th, 1775, to inter the body of his late commander, Captain Thomas Hayward, aged around thirty nine years.[23]

The captain’s friend, Edward Ommanney, began to settle Hayward’s estate immediately after his funeral. In the absence of other relatives, the London naval agent likely traveled to the captain’s home to make an inventory of his possessions. It is possible that Mr. Ommanney came across Hayward’s “Description of Charles Town” while searching through the late captain’s effects, and was sufficiently amused by the satirical verse to make a copy. Perhaps he shared it with his maritime contacts at the Carolina Coffee House in London, who likewise distributed additional copies to their friends. A few steps removed from the original source, readers of the entertaining “Description” were less familiar with the talented captain of HMS Martin, and the attribution was soon distorted into “Capt. Martin, captain of a man of war.”[24]

The passage of time might have obscured the name of its creator, but his “Description of Charles Town” still resonates with residents and visitors more than two and a half centuries after its creation. Arguably the most famous piece of verse about the Palmetto City, the 1769 “Description” is a remarkable work that merits a place in our community’s cultural memory. So, too, does its author, despite the uncertainty surrounding his identity. I believe Thomas Hayward to the be the most plausible candidate, and I’ve presented this brief outline of his career in an effort to illuminate the context in which the poem likely arose. Captain Hayward and HMS Martin visited Charleston eight times over a period of four years, spending a total of just over two hundred days in the colonial capital of South Carolina. He embraced the town’s social life with sufficient vigor to marry a local girl, then sailed home to an early grave and oblivion. By attaching his name to the famous “Description,” we revive his sarcastic wit and recall a fleeting moment of his vigorous life.

The passage of time might have obscured the name of its creator, but his “Description of Charles Town” still resonates with residents and visitors more than two and a half centuries after its creation. Arguably the most famous piece of verse about the Palmetto City, the 1769 “Description” is a remarkable work that merits a place in our community’s cultural memory. So, too, does its author, despite the uncertainty surrounding his identity. I believe Thomas Hayward to the be the most plausible candidate, and I’ve presented this brief outline of his career in an effort to illuminate the context in which the poem likely arose. Captain Hayward and HMS Martin visited Charleston eight times over a period of four years, spending a total of just over two hundred days in the colonial capital of South Carolina. He embraced the town’s social life with sufficient vigor to marry a local girl, then sailed home to an early grave and oblivion. By attaching his name to the famous “Description,” we revive his sarcastic wit and recall a fleeting moment of his vigorous life.

Historical documents like the small manuscript poem held at the South Caroliniana Library have the power to transport us back to distant ages and help us understand our cultural roots. Tapping into that power requires a lot of hard work, but I think it’s a worthwhile effort. In memory of Captain Hayward, therefore, I’ll close today’s program with a rhetorical question: This is the Charleston Time Machine—how do you like it?

[1] The document, measuring 23 cm tall, contains a partial watermark of a post-horn on a shield surmounted by a crown topped by three fleur-de-lis. Because this design was commonly used by a number of British paper makers in the eighteenth century, it might be impossible to determine the year of manufacture. For their generous and scholarly assistance with this document, I extend sincere thanks to McKenzie Lemhouse, Graham Duncan, and Edward Blessing at the South Caroliniana Library, and Dr. Michael Weisenburg of the Hollings Library Rare Books and Special Collections, at the University of South Carolina.

[2] Kenneth Silverman, “Two Unpublished Colonial Verses,” Bulletin of the New York Public Library 71 (1967): 62–63.

[3] H. Roy Merrens, ed., The Colonial South Carolina Scene: Contemporary Views, 1697–1774 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1977), 230–31.

[4] See, for example, Walter B. Edgar, South Carolina: A History (University of South Carolina Press, 1998), 155; Peter McCandless, Slavery, Disease, and Suffering in the Southern Lowcountry (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 3; Jennifer Van Horn, The Power of Objects in Eighteenth-Century British America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 87.

[5] Kevin Hayes, ed., The Cambridge History of American Poetry (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 133: “Martin’s other writings include ‘A Description of Charles Town in 1769,’ a short satirical poem told from an outsider’s point of view that critiques the natural and social world of Charleston, South Carolina.” Hayes cites only Silverman’s 1967 essay, but that source does not include any discussion of the author’s identity.

[6] At the National Archives of the United Kingdom (hereafter NAUK) on 7 January 2020, I examined the finding aid for ADM 6/3–18, a large collection of Commission and Warrant Books of the British Admiralty spanning from 1695 to 1758. The typescript finding aid contains an alphabetical index of all commissioned officers (midshipmen, lieutenants, captains, etc.) in the Royal Navy and a brief digest of their respective assignments. In addition to this finding aid, several published sources present lists of British naval officers drawn from extant Admiralty records: John Charnock, Biographia Navalis; or, Impartial Memoirs of the Lives and Characters of Officers of the Navy of Great Britain, from the Year 1660 to the Present Time (six volumes; London: R. Faulder, 1794–98); Isaac Shomberg, Naval Chronology; Or, An Historical Summary of Naval & Maritime Events (five volumes; London: T. Egerton, 1802); David Bonner-Smith, et al., eds., “Commissioned Officers of the Royal Navy, 1660–1815” (typescript, 1954; available at NAUK and via Ancestry.com). Alexander Martin (1740–1807) appears in none of these sources.

[7] For a chronological list of naval vessels visiting Charleston between 1720 and 1775, see W. E. May, “His Majesty’s ships on the Carolina Station,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 71 (July 1970): 162–69. For details of William Martin’s activities in Charleston, see the captain’s logbook of HMS Blandford, 13 March 1720/1–25 November 1724, at NAUK, ADM 51/4126. The will of Admiral William Martin was probated on 19 October 1756 (NAUK, PROB 11/825/276).

[8] All of these ships are mentioned in May, “His Majesty’s ships on the Carolina Station,” 168–69, and in the local newspapers of 1769. For more information about HMS Martin, see Rif Winfield, British Warships in the Age of Sail, 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates (Barnsley, U.K.: Seaforth, 2007), 417, 424–25.

[9] Hayward’s service records are found at NAUK; see Royal Navy Passing Certificates, ADM 107/5/196 (3 March 1756); Admiralty Commission and Warrant Books, ADM 6/19/362 (HMS Spy, 9 November 1761); ADM 6/19/495 (HMS Senegal, 10 May 1763); ADM 6/20/171 (HMS Martin, 11 June 1767); Captain’s log for HMS Spy, 6 December 1761–21 January 1763, ADM 51/924; Captain’s log for HMS Senegal, 10 May 1763–31 May 1764, ADM 51/884; Captain’s log for HMS Senegal, 1 June 1764–10 February 1767, ADM 51/885; Captain’s log for HMS Martin, 11 June 1767–10 June 1771, ADM 51/580; Captain’s log for HMS Martin, 11 June 1771–26 December 1771, ADM 51/581.

[10] South Carolina Gazette (hereafter SCG), 30 November 1767 (Monday), No. 1679, page 2: “Charles-Town, November 30. . . . Last Thursday [26 November] arrived here from England, his Majesty’s ship Martin, commanded by Thomas Heyward [sic], Esq; stationed at North Carolina, in the room of the Hornet, (Capt. Jeremiah Morgan) ordered home.” SCG, 14 December 1767 (Monday), No. 1681, page 2: “Charles-Town, December 14. . . . Wednesday [9 December] sailed for her station at North Carolina, his Majesty’s ship Martin, commanded by Capt. Thomas Heyward [sic].”

[11] See the local news in SCG, 2 May 1768, page 3; SCG, 23 May 1768, page 3.

[12] Boston News-Letter, 6 October 1768.

[13] South Carolina Gazette and Country Journal (hereafter SCGCJ), 10 January 1769, page 1.

[14] See the local news in SCGCJ, 11 April 1769, page 2; SCG, 11 May 1769, page 3; SCG, 1 June 1769, page 3.

[15] SCGCJ, 20 March 1770, page 2; SCG, 29 March 1770, page 2; South Carolina and American General Gazette (hereafter SCAGG), 13–20 April 1770, page 3; SCGCJ, 1 May 1770, page 2.

[16] John Sinclair and Sarah Cartwright married at St. Philip’s Anglican Church on 24 June 1749, and welcomed a daughter, Sarah, on 2 May 1750. Anne was born sometime between 1751 and 1755, but does not appear in the extant registers of that church. See A. S. Salley Jr., ed., Register of St. Philip’s Parish, Charles town, South Carolina, 1720–1758 (Charleston, S.C.: Walker, Evans & Cogswell, 1904), 98, 191; D. E. Huger Smith and A. S. Salley Jr., eds., Register of St. Philip’s Parish, Charles Town, or Charleston, S.C., 1754–1810 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1927), 193; James Raven, London booksellers and American Customers: Transatlantic Literary Community and the Charleston Library Society, 1748–1811 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2002), 37.

[17] SCG, 3 May 1770, page 2; SCGCJ, 8 May 1770, page 2; SCG, 10 May 1770, page 4.

[18] SCAGG, 27 August–3 September 1770, page 2; SCG, 20 September 1770, page 3; SCGCJ, 6 November 1770, page 3; SCG, 8 November 1770, page 4.

[19] SCGCJ, 26 March 1771, page 2; SCGCJ, 14 May 1771, page 2; SCAGG, 10–17 June 1771, page 2; Boston Evening-Post, 1 July 1771, page 2.

[20] Boston Evening-Post, 1 July 1771, page 2; Boston Post-Boy, 23 September 1771, page 3; Massachusetts Spy, 26 September 1771, page 2; SCG, 17 October 1771, page 2; SCGCJ, 22 October 1771, page 3. I have not yet examined the extant correspondence between the Admiralty and Captain Hayward held at NAUK to discover the motivation behind the Martin’s curious route in the summer and fall of 1771.

[21] Edward Ommanney, then of America Square, London, proved the will of Thomas Hayward on 19 September 1775; see NAUK, PROB 11/1011/239

[22] NAUK, ADM 6/21/33 (3 June 1774).

[23] The Hayward family burial dates are found in Cornwall Family History Society, Cornwall Burials, FP133 1/6, retrieved from Findmypast.com on 12 April 2021. For James’s diary, see John Knox Laughton, ed., Journal of Rear-Admiral Bartholomew James 1752–1828, Publications of the Navy Records Society, volume 6 (London: Navy Records Society, 1896), 15.

[24] The will of Edward Ommanney of Bloomsbury Square, Middlesex, was probated on 11 February 1811; see NAUK, PROB 11/1519/161.

NEXT: The Telegraph: Charleston’s First Information Superhighway

PREVIOUSLY: Granville Bastion and the Unfinished Fort of 1697

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments