The Sales of Incoming Africans on the Wharves of Colonial Charleston

Processing Request

Processing Request

The entry of more than 150,000 African captives into the port of Charleston before the year 1808 forms one of the most important themes in the history of this community, but there are many local details about this international traffic in human cargo that remain obscure. To acknowledge the suffering of those people and to honor their legacy, many people wish to retrace their first footsteps onto this American shore. But where did they stand when they were sold into a life of slavery here in Charleston?

In my conversations about Charleston history with professional tour guides and visitors to our fair city, I often hear questions about specific details of the business of slavery. One of the most basic of these questions is also one of the most difficult to answer: Where in Charleston were enslaved people bought and sold? The beginning of any attempt to answer this question starts with a disclaimer about two important variables. First, the locations of the sales of enslaved people depends on whether we’re talking about newly-imported people being sold for the first time in South Carolina, or people who have already been here for some time and are being sold again (for whatever reason). Second, the geography of these sales evolved over time, so the answer (or range of answers) depends on the chronology in question. In short, we have to subdivide that simple query about where people were sold into a series of more specific questions.

For example, we can ask such questions as: Where were newly-imported enslaved people sold in Charleston during the colonial era? In the years immediately after the American Revolution? In the final years of the legal importation of Africans, from January 1804 through December 1807? Likewise, one could ask a similar set of questions about the local sales of enslaved people already residing in the Lowcountry during the colonial era, the post-Revolutionary era, and all they way up to the era of the Civil War. There are different answers for each permutation of the question, and there is no simple solution for any aspect of this thorny issue. In an effort to provide some answers, however, I’m going to try to tackle this sprawling subject in a series conversations that I’ll spread out over the coming weeks and months. I’d like to begin with a fairly simple and straightforward portion: Where in Charleston were newly-arrived enslaved people sold during the colonial era?

Most of the once-voluminous paper records created in early Charleston in conjunction with the trafficking of enslaved people has long since disappeared. Because of this loss of locally-produced records, it is now very difficult to reconstruct the details surrounding the commercial process of landing the people who were transported across the Atlantic Ocean and offered for sale as human cargo in our town. The magnificent website SlaveVoyages.org contains a wealth of information about the international trade in enslaved Africans between the early 1500s and the late 1800s, including robust data about the traffic to the port of Charleston, that is drawn from surviving shipping and insurance records that exist in archives beyond South Carolina. That massive international database contains no local details about what happened to those people once they arrived in Charleston harbor. For that sort of specific data, we have to look into local archives for clues.

Most of the once-voluminous paper records created in early Charleston in conjunction with the trafficking of enslaved people has long since disappeared. Because of this loss of locally-produced records, it is now very difficult to reconstruct the details surrounding the commercial process of landing the people who were transported across the Atlantic Ocean and offered for sale as human cargo in our town. The magnificent website SlaveVoyages.org contains a wealth of information about the international trade in enslaved Africans between the early 1500s and the late 1800s, including robust data about the traffic to the port of Charleston, that is drawn from surviving shipping and insurance records that exist in archives beyond South Carolina. That massive international database contains no local details about what happened to those people once they arrived in Charleston harbor. For that sort of specific data, we have to look into local archives for clues.

The earliest enslaved Africans who came to this colony were not imported for the purpose of sale; rather, they accompanied established West Indian planters seeking to acquire new property in South Carolina. Shortly thereafter, individual planters here began sending orders to agents in the English West Indian colonies to purchase specific numbers of enslaved people for their own use (again, not for the purpose of public sale). In both of these cases, the vessels transporting these enslaved people from the West Indies either landed first at Albemarle Point, the original site of Charles Town in 1670 (now Charles Towne Landing State Historic Site) or sailed up one of the Lowcountry rivers to the plantation on which the enslaved people were destined to work.

We don’t know precisely when the first enslaved people of African descent were brought to Charleston as a speculative venture; that is, specifically for the purpose of public sale. This practice likely began in the 1690s, and increased rapidly after 1698, when the Royal African Company lost its monopoly on the exportation of African captives to the English colonies. By that time, the port of Charles Town was well-established at the present site on the peninsula between the Ashley and Cooper Rivers (where it moved in 1680). The earliest vessels carrying these “speculative” consignments of enslaved people sailed from the West Indian colonies, not directly from Africa. A few merchants, like Captain William Rhett, made a handful journeys from Charleston to Africa and back as early as 1698, but the human traffic directly between West Africa and the Palmetto City was generally a minor part of the trade until around the year 1710. From that point onward, the number of voyages directly from Africa to Charleston steadily increased, while the customary trans-shipment of enslaved Africans from the West Indies to Charleston continued.[1]

The surviving documentary records of early South Carolina contain very little specific evidence related to the location and method of the sales of cargoes of newly-imported enslaved people in Charleston prior to the advent of the town’s first printed newspaper in January 1732. From that moment to the beginning of the Revolutionary War in 1775, however, the weekly newspapers provide valuable information that helps us to draw conclusions about the routine practices associated with this traffic.

The surviving documentary records of early South Carolina contain very little specific evidence related to the location and method of the sales of cargoes of newly-imported enslaved people in Charleston prior to the advent of the town’s first printed newspaper in January 1732. From that moment to the beginning of the Revolutionary War in 1775, however, the weekly newspapers provide valuable information that helps us to draw conclusions about the routine practices associated with this traffic.

Each issue of Charleston’s early newspapers includes a list of commercial sailing vessels that have recently arrived in the harbor. This list provides the name of each vessel, its rigging type (ship, brigantine, sloop, pink, snow, etc,), the name of its captain or commander, and the name of the port from which it last sailed. Although it does not include a description of their respective cargoes, or tell us where the respective vessels were docked, this maritime information provides useful clues. We can safely assume, for example, that vessels arriving directly from Africa were carrying enslaved people. Vessels arriving from Caribbean islands such as Antigua, Barbados, and Jamaica, might have been carrying enslaved people, but such vessels routinely brought non-human cargo as well. The massive database at SlaveVoyages.org helps us to identify known slaving vessels, of course, but that wonderful online resource seems to have overlooked a number of vessels carrying relatively small cargos of people from the Caribbean islands to Charleston.

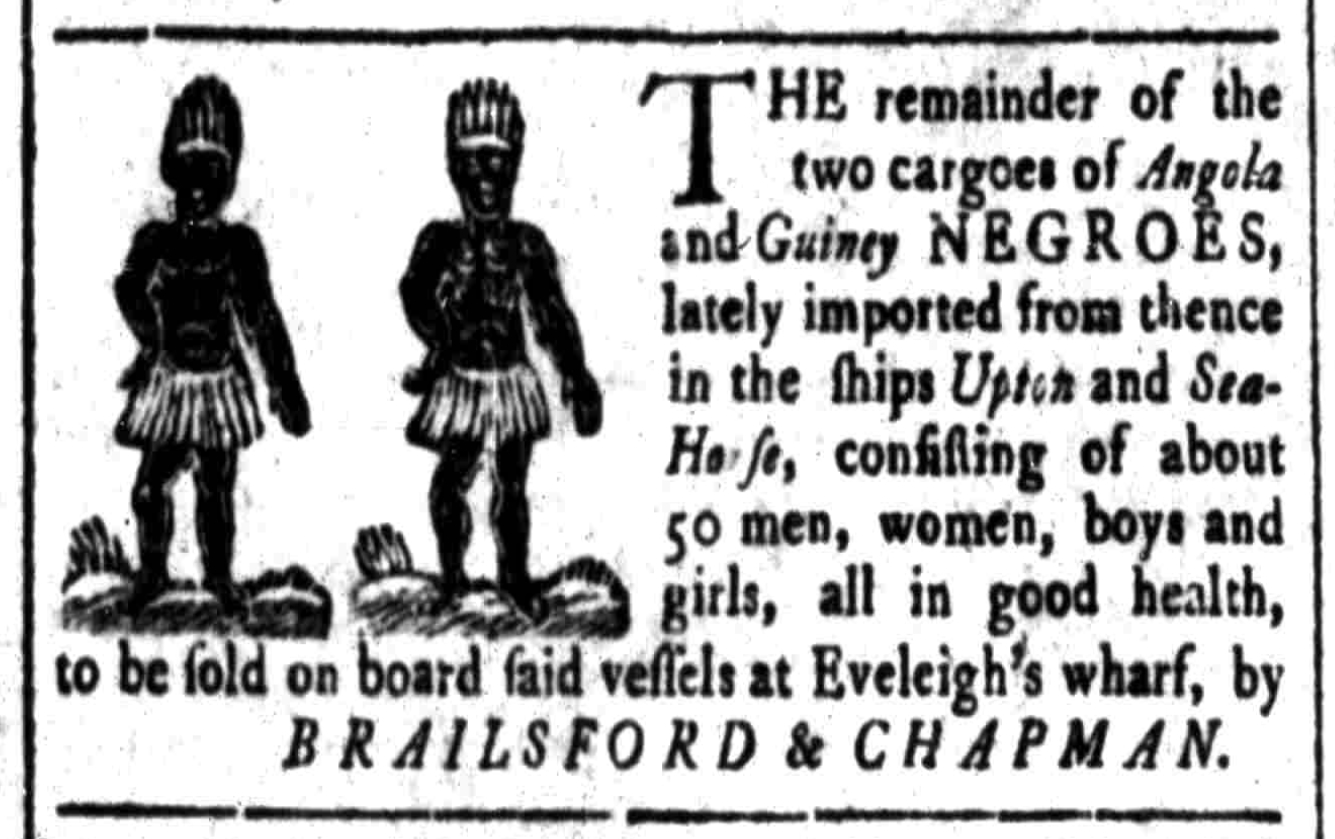

Beginning in the autumn of 1732, our local newspapers also began including advertisements or notices of upcoming sales of the recently-arrived cargoes of enslaved people. Advertisements for most, but not quite all, of the incoming cargos appear in the surviving newspapers, but these notices do not provide the level of detailed information that we might hope to see. Many, but certainly not all, mention the number of people being offered for sale. The majority of these notices do not specify the geographic location of the sale. Besides identifying the name of the vessel and providing the date of the commencement of the sale, most of these advertisements simply note that the sale will take place “on board” the vessel in question. A minority of the surviving sale notices specify the name of the wharf at which the vessel was docked (or would be docked on the date of the sale).

I’m working on a long-term project to assemble a spreadsheet containing information about every slave vessel mentioned in Charleston’s colonial-era newspapers. Building on and extending the seminal work contained in the online database at SlaveVoyages.org, I’m trying to capture Charleston-specific data that will help complete the story of the trans-Atlantic journeys that brought captive Africans to our community. My unfinished spreadsheet includes the arrival dates of the approximately 450 slave cargos mentioned in the colonial-era newspapers and the dates, numbers, and locations (if given) of the advertised sales of their enslaved cargos. The goal is to provide detailed local information that we can use to better narrate the story of Charleston’s history to the members of our community and the millions of people who visit the city every year.

This is an on-going venture that’s not yet ready for public consumption, but I’ve done enough work to draw one general but very useful conclusion that probably holds true for the entire era of importing African captives into the port of Charleston, from the late seventeenth century to the legal end of the trade at the beginning of the year 1808: Cargos of newly-imported people were routinely sold on the deck of the vessel that transported them into Charleston harbor, while that vessel was docked alongside one of the wooden wharves that extended eastward from East Bay Street into the Cooper River. That broad statement then begs a more specific query: At which of the town’s wharves did slave ships dock?

This is an on-going venture that’s not yet ready for public consumption, but I’ve done enough work to draw one general but very useful conclusion that probably holds true for the entire era of importing African captives into the port of Charleston, from the late seventeenth century to the legal end of the trade at the beginning of the year 1808: Cargos of newly-imported people were routinely sold on the deck of the vessel that transported them into Charleston harbor, while that vessel was docked alongside one of the wooden wharves that extended eastward from East Bay Street into the Cooper River. That broad statement then begs a more specific query: At which of the town’s wharves did slave ships dock?

The story of the physical evolution of Charleston’s waterfront along East Bay Street is a complicated topic we’ll save for future programs. For the present purposes, I’ll mention a few important facts that might help you visualize the slow proliferation of wooden wharves along the Cooper River waterfront. During the first decade of life here at “new” Charles Town, established at the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper Rivers in 1680, the waterfront we call East Bay Street was known simply as “the wharf of Charles Town” (see Episode No. 180). Large and even medium-sized sailing vessels anchored a few hundred feet off shore and carried cargo and passengers to-and-fro by means of small row boats and barges or “lighters.” By the year 1690, Landgrave Thomas Smith had a built “wharf” of some sort near the east end of what became known as Longitude Lane, but it’s unclear how far it projected outward from land into the Cooper River.[2] In 1698, the Lords Proprietors of Carolina began granting marsh lots on the east side of East Bay to the owners of lots on the west side of that street, on condition that each owner would build part of a long brick seawall to stabilize the muddy waterfront. That granting process facilitated the development of an evolving series of wooden wharves projecting eastward into the Cooper River.

The 1711 illustration of Charleston known as the “Crisp map” shows two “bridges” or wharves on the east side of East Bay Street: One owned by Landgrave Thomas Smith, just a bit south of the east end of Tradd Street, and one built sometime around the turn of the eighteenth century by William Rhett, located slightly north of Broad Street. The database of known trans-Atlantic slave voyages, found at SlaveVoyages.org, provides our best knowledge of the number of cargoes sailing to Charleston during the early 1700s, at which time those ships probably docked at either Smith’s wharf or Rhett’s wharf.

The map of Charleston published in 1739 with the title “Ichnography of Charles-Town at High Water” shows eight “bridges” or wharves on the east side of East Bay Street, in the following order from south to north: Brewton’s wharf, located just north of Granville Bastion, approximately where the Carolina Yacht Club stands today, then Lloyd’s, Pinckney’s, Motte’s, Elliott’s, Middle, Rhett’s, and Crokatt’s wharf, located just north of Unity Alley. It appears from this map that Smith’s wharf was renamed Pinckney’s wharf, but it’s difficult to know for sure because no one has yet produced a chronological history of the construction of Charleston’s numerous wharves. We know that various wharves were re-named very few years, as the respective properties were sold and re-sold to a series of owners, but currently we don’t have a tool to help us track over time the appearance of newly-built wharves and the re-naming of old ones. This is not an impossible task, it’s just going to take a lot of time and effort, and I’m hoping someone else will take on that big project.

The map of Charleston published in 1739 with the title “Ichnography of Charles-Town at High Water” shows eight “bridges” or wharves on the east side of East Bay Street, in the following order from south to north: Brewton’s wharf, located just north of Granville Bastion, approximately where the Carolina Yacht Club stands today, then Lloyd’s, Pinckney’s, Motte’s, Elliott’s, Middle, Rhett’s, and Crokatt’s wharf, located just north of Unity Alley. It appears from this map that Smith’s wharf was renamed Pinckney’s wharf, but it’s difficult to know for sure because no one has yet produced a chronological history of the construction of Charleston’s numerous wharves. We know that various wharves were re-named very few years, as the respective properties were sold and re-sold to a series of owners, but currently we don’t have a tool to help us track over time the appearance of newly-built wharves and the re-naming of old ones. This is not an impossible task, it’s just going to take a lot of time and effort, and I’m hoping someone else will take on that big project.

Getting back to our main topic, the number of East Bay Street wharves, constructed of palmetto-log cribs sunk into the mud and topped with broad wooden planks, continued to grow as the years passed. A newspaper report of a severe storm in the summer of 1770 names fifteen wharves along the east side of East Bay Street, stretching from the present site of the Carolina Yacht Club on the south to the vicinity of Cumberland Street on the north, just a bit south of Craven Bastion (now the site of the U.S. Custom House).[3] The Phoenix fire insurance map of Charleston, surveyed in 1788 and published in 1790, depicts seventeen wharves along the east side of East Bay Street, all south of modern Market Street, as well as a few new wharves north of Market Street that were built after the American Revolution.

I’ve found colonial-era advertisements for the sales of what they called “new Negroes,” or newly arrived enslaved people, at the following wharves (in no particular order): Elliott’s, Motte’s, Mayne’s, Graeme’s, Eveleigh’s, Dandridge’s, Burn’s, and Roper’s. I’m sure I’ve missed a few wharves, but I’m working towards a comprehensive collection of data that matches the sales of newly-arrived slave cargos and specific sale locations. In short, however, I feel confident that we can distill this information down to a reasonably accurate and acceptable summary statement that builds on our earlier conclusion:

Cargos of newly-imported people were routinely sold on the deck of the vessel that transported them into Charleston harbor, while that vessel was docked alongside one of the wooden wharves that extended eastward from East Bay Street into the Cooper River. Most of the surviving printed notices of the sales that took place prior to the commencement of the American Revolution in 1775 do not specify the name of the wharves in question, but the volume and regularity of the traffic, especially in the last decade before that war, suggest that these sales could have taken place at any one of the fifteen to seventeen wharves located between Granville Bastion on the south and Craven Bastion on the north.

Cargos of newly-imported people were routinely sold on the deck of the vessel that transported them into Charleston harbor, while that vessel was docked alongside one of the wooden wharves that extended eastward from East Bay Street into the Cooper River. Most of the surviving printed notices of the sales that took place prior to the commencement of the American Revolution in 1775 do not specify the name of the wharves in question, but the volume and regularity of the traffic, especially in the last decade before that war, suggest that these sales could have taken place at any one of the fifteen to seventeen wharves located between Granville Bastion on the south and Craven Bastion on the north.

It’s unclear to me, however, whether a customer hoping to purchase enslaved people was obliged to climb aboard the vessel in question to view the available stock, or stood on the wharf next to the vessel and watched its crew parade the enslaved people across the deck. I suspect that both options were possible, depending on the size of the vessel and the number of people being offered for sale. It’s also unclear to me whether these sales were conducted like a conventional auction, with an auctioneer barking descriptions of one person at a time, or whether customers browsed the available stock in a more informal manner and then negotiated with a sales agent for the purchase of individuals or groups of people. If there was an auctioneer present, or someone acting as a sort of master-of-ceremonies, then who was that person? Was it the wealthy merchant or merchants who had funded the entire venture and thus owned the cargo, or was it another agent hired to conduct the horrible business? The surviving newspaper resources don’t address these points, so I’ll keep looking for answers elsewhere.

The vast majority of newly-arrived cargos of enslaved people brought to Charleston were sold onboard vessels that brought them here, but there were exceptions to the rule. I’ve found a few colonial-era newspaper items that mention the sales of newly-arrived people at other nearby locations. I suspect that such exceptions were related to the number of individuals offered for sale. While a slave merchant might consider it dangerous and foolish to disembark a large number of justifiably angry, hostile captives and march them to a nearby location for sale, that same merchant might consider it safe to land a small number of people—perhaps a portion of a larger consignment, or the cargo of a small vessel, or a group of children—and sell them at a location more convenient for his customers.

In June of 1739, for example, Joseph Wragg advertised to sell “a choice cargo of young healthy Negroes” at his office on the west side of East Bay Street, opposite the wharves, “where the Secretary’s Office was lately kept in Charlestown.”[4] In January of 1756, Charles Mayne offered a reward for the return of a newly-arrived “Gambia negro boy” who had been kidnapped “from the store on my wharf where the new negroes are selling.”[5] This structure would have been a low wooden clapboard shed on Mr. Mayne’s wharf, as there were no permanent buildings of any kind built on Charleston’s wharves until after the American Revolution.

In June of 1739, for example, Joseph Wragg advertised to sell “a choice cargo of young healthy Negroes” at his office on the west side of East Bay Street, opposite the wharves, “where the Secretary’s Office was lately kept in Charlestown.”[4] In January of 1756, Charles Mayne offered a reward for the return of a newly-arrived “Gambia negro boy” who had been kidnapped “from the store on my wharf where the new negroes are selling.”[5] This structure would have been a low wooden clapboard shed on Mr. Mayne’s wharf, as there were no permanent buildings of any kind built on Charleston’s wharves until after the American Revolution.

In future programs, I’m going to continue this line of geographical inquiry into the era immediately after the Revolutionary War, and then into the final era of slave importations between January 1804 and December of 1807. For the moment, however, I’d like to stick to the colonial era and contrast today’s topic with the other side of the original question. We’ll continue this conversation by exploring the geographic details of the sales of enslaved people who had already been in South Carolina for some period of time—the people who were uprooted from their local lives and families in the years before the American Revolution. When those people were brought to urban Charleston for sale, their path diverged from that tread by their brothers and sisters who stood nearby on the decks of foul, rotting ships. Next week we’ll follow their trail to an important but long-forgotten auction site once known as “the usual place.”

[1] There is a rich body of scholarly literature devoted the traffic of enslaved people into colonial-era Charleston. See, for example, Elizabeth Donnan, “The Slave Trade into South Carolina Before the Revolution,” American Historical Review 33 (July 1928): 804–28; David Eltis, “The Volume and Structure of the Transatlantic Slave Trade: A Reassessment,” William and Mary Quarterly 58 (January 2001): 17–46; Peter Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion (New York: W. W. Norton, 1974); David Eltis and David Richardson, ed., Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010); and Daniel Littlefield, Rice and Slaves: Ethnicity and the Slave Trade in Colonial South Carolina (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1991).

[2] Mabel L. Webber, ed., “Letters from John Stewart to William Dunlop,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 32 (January 1931): 32. Stewart did not specify the location of Smith’s wharf in 1690, but the “Crisp Map” of 1711 places it south of the east end of Tradd Street, in front of Town Lot No. 5, which Smith owned.

[3] South Carolina Gazette, 7 June 1770. The wharves mentioned, in south-north order, are Roper’s, Eveleigh’s, Raven’s, Graeme’s, Market, Motte’s, Elliott’s, Beale’s, Champneys’s, Beresford’s, Burn’s, Price’s, Wragg’s, Rose’s, and Russell’s.

[4] South Carolina Gazette, 2–9 June 1739.

[5] South Carolina Gazette, 29 January 1756 (supplement).

PREVIOUS: Indigo in the Fabric of Early South Carolina

NEXT: The Auction Sales of Enslaved Residents in Colonial Era Charleston

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments