Where Did Robert Smalls Live in 1862 Charleston?

Processing Request

Processing Request

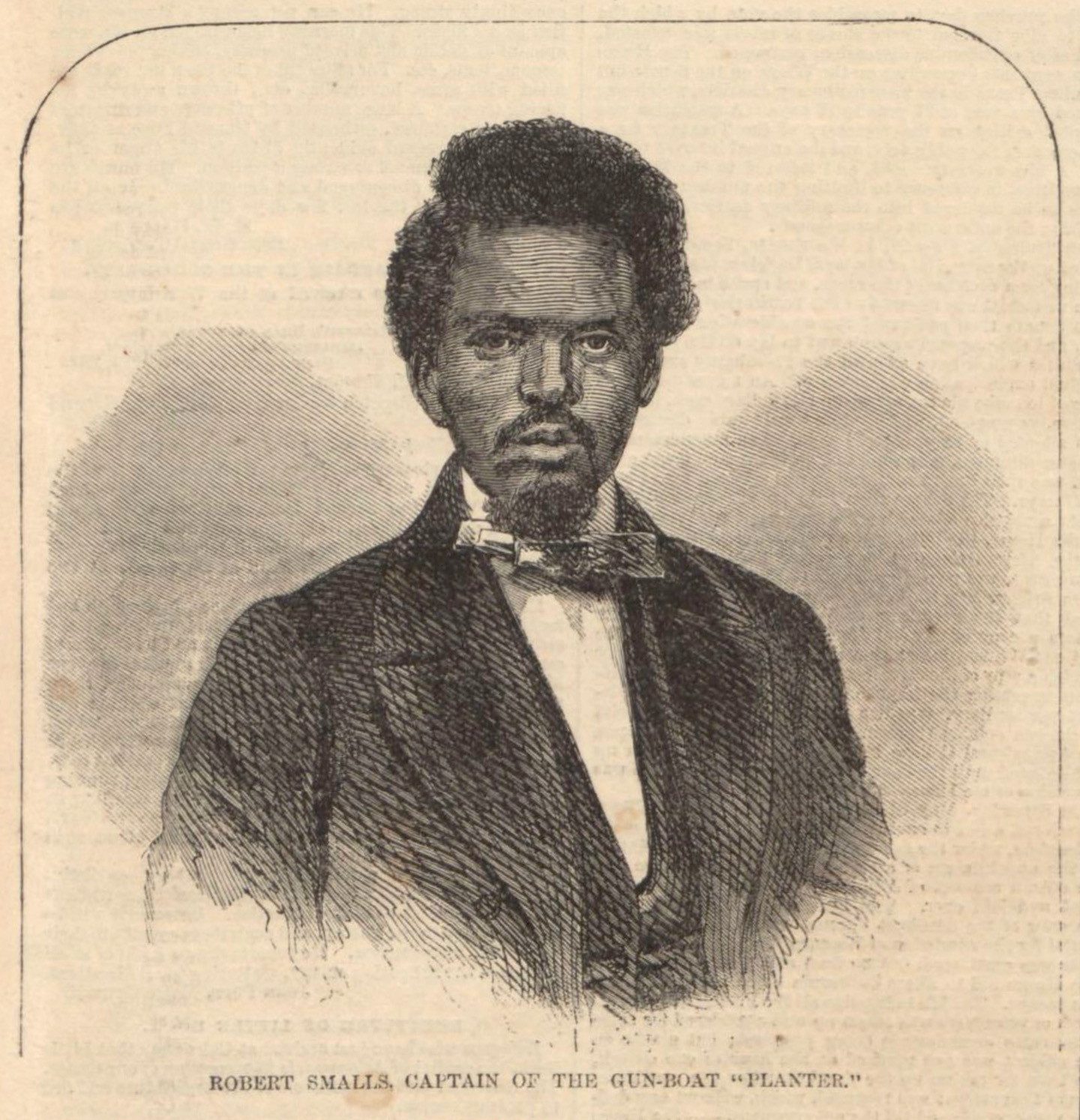

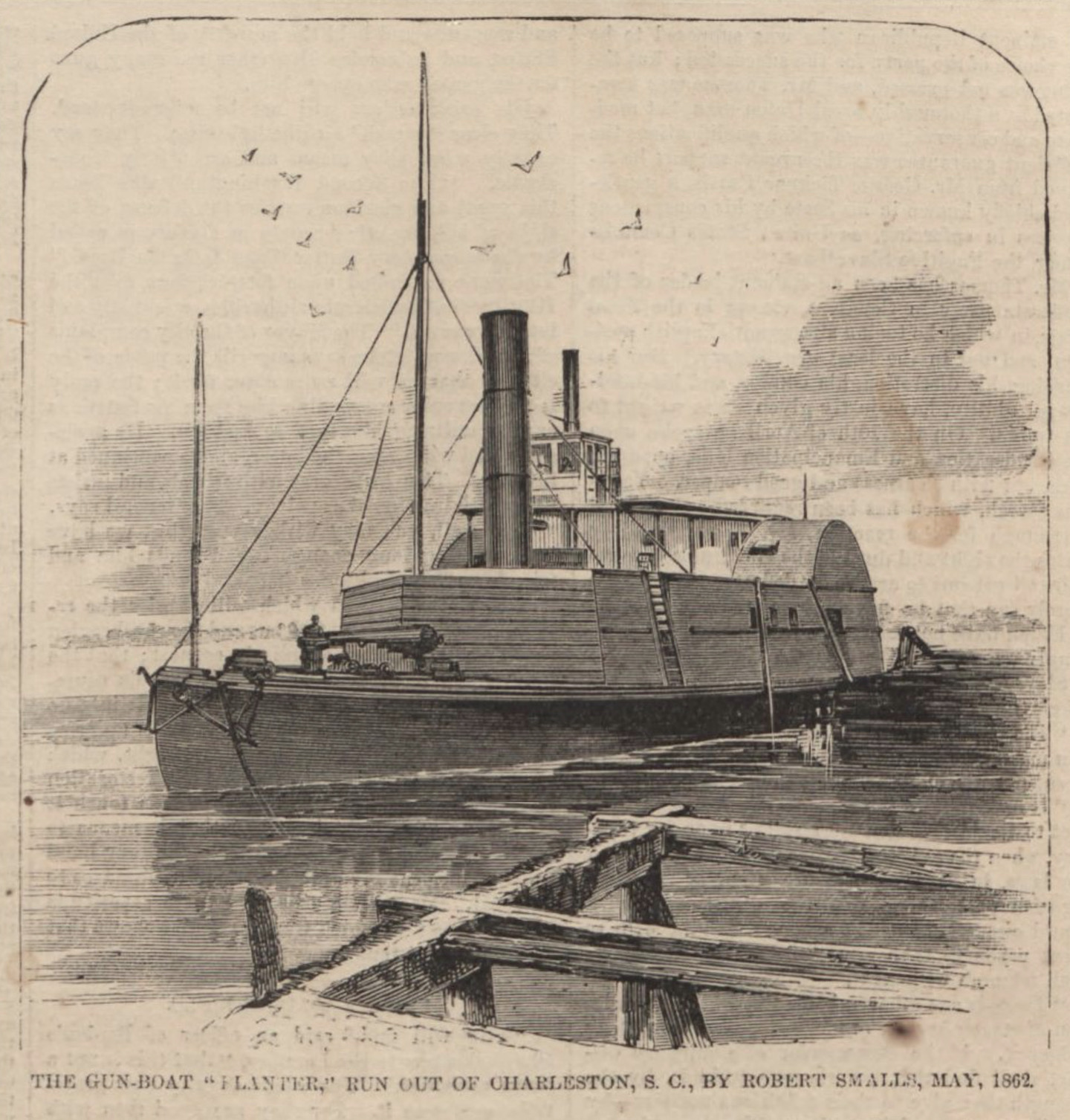

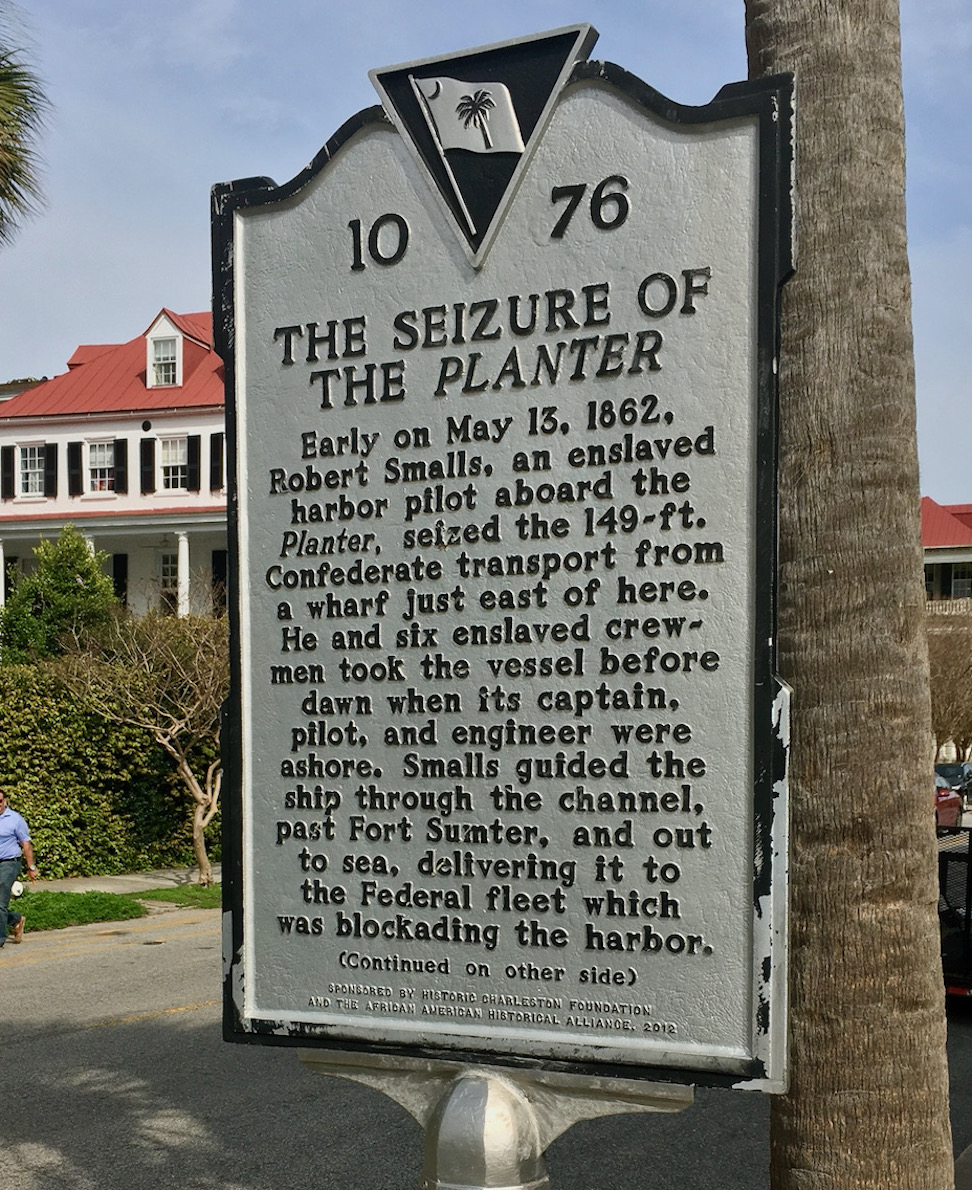

Robert Smalls became an American icon when he absconded from Charleston with the steamboat Planter in May 1862 to free his family and friends from the bonds of slavery. To better understand his early life, inquiring minds want to identify the location of Smalls’ urban residence in the years preceding his famous escape: was it a house or a stable or a loft, perhaps located near the waterfront? Today we’ll sift the evidence of Smalls’ decade in the Palmetto City and examine the clues that might point to a specific site.

Several months ago, the Mayor’s Office of the City of Charleston asked me to investigate this topic as part of the city’s ongoing efforts to promote a more inclusive and accurate narrative of local history. I agreed to delve into this antebellum topic because I’ve spent a lot of time with historic property records in the Charleston area, and the idea of locating Robert Smalls’ residence seemed like a reasonably finite goal. Months later, I’ve completed my research and formed a conclusion. The answer is anything but simple, and the journey leading to it has been difficult. To add credence to my conclusions, I’ll narrate the various steps along the path of this investigation and frame the solution to this puzzle within a conversation about the potential pitfalls in the pursuit of historical research. Let’s begin with a brief summary of our main character, just to ensure that everyone understands the desire to identify the location of his residence in urban Charleston.

Robert Smalls was born in Beaufort, South Carolina, in 1839 to an enslaved woman named Lydia, who was legally owned by a wealthy planter named Henry McKee. When Robert was around twelve years of age, Mr. McKee sent him to work and live in the City of Charleston, where he was employed in a variety of occupations for a decade. Like other enslaved people who were “hired out” to work beyond the residence of their legal owners, Robert paid the majority of his wages to Henry McKee. He gained experience during the mid-1850s as a hostler, dock worker, and then rigger—seasonal jobs that occupied the cooler months of the year when the port was busiest. During the warmer months, when dock work was at a low ebb, Robert worked as a boatman and gained an intimate knowledge of local waterways.[1] In 1861, he joined the crew of the Planter, a commercial steamboat hired by the nascent Confederate government to support defensive operations in the area. In early May 1862, Robert and several of his fellow enslaved crewmen met at his “house” to form a plan to take the Planter from Charleston’s waterfront and steam out to the United States Navy vessels then blockading the entrance to the port.[2] Robert set his plan in motion on the evening of May 12th, 1862. Before sunrise on May 13th, he successfully piloted the Planter past Fort Johnson, Fort Sumter, and Fort Moultrie. Confederate officials in Charleston and around the harbor did not realize that the Planter had been stolen by a rogue crew until the vessel was beyond the reach of their guns. At sunrise, Robert Smalls delivered the Planter to representatives of the U.S. Navy, and commenced a long period of public service to the people of his country and the state of South Carolina.

As with any new research project, I commenced my search by surveying the existing body of literature devoted to the life and times of Robert Smalls. Several biographical monographs have been published in the past fifty years, as well as a number of journal and magazine articles and even children’s books. After a quick tour of the most relevant literature, I digested a basic outline of Robert’s decade in Charleston as reported by a consensus of recent historians: He arrived in the city in 1851 and resided on a property owned by the Ancrum family, relatives of Henry McKee’s wife. Robert worked briefly at the Planters’ Hotel and then as a lamplighter before joining the team of a White stevedore and rigger named “John Simmons.” He met an enslaved woman named Hannah Jones, whom he married in late 1856. After the newlyweds gained permission from their respective owners to live together, Robert rented two rooms above a livery stable on East Bay Street, where he tended the horses to help cover the rent. Smalls joined the crew of the Planter in 1861, and the rest, as they say, is history.[3]

From this cursory review of the existing literature, we can identify two potential residential sites within urban Charleston—an Ancrum family property and then a livery stable on East Bay Street. I pursued each of these targets separately, and I’ll describe the process for each in turn.

A bit of genealogical research revealed that Henry McKee (1811–1875), who owned Robert Smalls, was married to Jane Bold (1819–1904) of Beaufort. Jane’s younger sister, Eliza Bold (1821–1907) married in 1840 James Hasell Ancrum II (1820–1860) of Charleston. Sometime in 1851, says the biographical literature, Robert Smalls was sent to Charleston to reside in an outbuilding behind the urban residence of Eliza Bold Ancrum, the sister-in-law of Henry McKee. Armed with these details, I went to the Charleston County Register of Deeds office to find the address of Ancrum’s Charleston residence.

A bit of genealogical research revealed that Henry McKee (1811–1875), who owned Robert Smalls, was married to Jane Bold (1819–1904) of Beaufort. Jane’s younger sister, Eliza Bold (1821–1907) married in 1840 James Hasell Ancrum II (1820–1860) of Charleston. Sometime in 1851, says the biographical literature, Robert Smalls was sent to Charleston to reside in an outbuilding behind the urban residence of Eliza Bold Ancrum, the sister-in-law of Henry McKee. Armed with these details, I went to the Charleston County Register of Deeds office to find the address of Ancrum’s Charleston residence.

James Hasell Ancrum II owned quite a bit of property in the City of Charleston and across the South Carolina Lowcountry. Through his father and paternal grandmother, he inherited a large share of the subdivision of the suburban plantation once known as Rhettsbury (see Episode No. 53). Furthermore, his mother, Jane Washington Ancrum (1783–1866), inherited numerous properties and resided within the William Washington House at the corner of South Bay and Church Streets. I traced the titles of several Ancrum addresses within the city, but most, if not all, seemed to be investment properties, and none formed an obvious principal residence for James and Eliza Ancrum. Back at CCPL’s South Carolina History Room, I turned to the city directories published in Charleston in the decade before the Civil War and found a spotty record of this couple. James and Eliza appear only occasionally in the directories, and their address changed repeatedly over the years. In short, it appears that the Ancrums followed a residence pattern shared by hundreds of other wealthy landowners in the antebellum Lowcountry: they moved seasonally between town and county, and often (or usually) rented furnished accommodations within urban Charleston during the city’s social season.[4]

Frustrated in my efforts to pinpoint an Ancrum residence, I turned my attention to the task of locating the site occupied by Robert and Hannah Smalls after their marriage in 1856. Several writers in the past half-century have stated that the couple shared a two-room apartment above a livery stable on East Bay Street. To refine my search for such a place, I examined maps, plats, city directories, and the titles of numerous properties along Charleston’s principal commercial thoroughfare of the 1850s. I quickly learned a sobering fact: there were no livery stables on East Bay Street at any point in the nineteenth century. A livery stable is a specific kind of equine facility—a large commercial structure housing numerous horses owned by different clients or available for hire. It is distinct from a regular stable in the same way that a full-service parking garage is distinct from the driveway of a private residence. East Bay Street in the 1850s looked much like it does today, crowded with a variegated mix of commercial structures. The city hosted a number of large livery stables at that time, but they were all located farther to the west of East Bay Street, away from the busy maritime commerce that dominated Charleston’s waterfront.

Frustrated in my efforts to pinpoint an Ancrum residence, I turned my attention to the task of locating the site occupied by Robert and Hannah Smalls after their marriage in 1856. Several writers in the past half-century have stated that the couple shared a two-room apartment above a livery stable on East Bay Street. To refine my search for such a place, I examined maps, plats, city directories, and the titles of numerous properties along Charleston’s principal commercial thoroughfare of the 1850s. I quickly learned a sobering fact: there were no livery stables on East Bay Street at any point in the nineteenth century. A livery stable is a specific kind of equine facility—a large commercial structure housing numerous horses owned by different clients or available for hire. It is distinct from a regular stable in the same way that a full-service parking garage is distinct from the driveway of a private residence. East Bay Street in the 1850s looked much like it does today, crowded with a variegated mix of commercial structures. The city hosted a number of large livery stables at that time, but they were all located farther to the west of East Bay Street, away from the busy maritime commerce that dominated Charleston’s waterfront.

Adopting a more relaxed interpretation of the biographical literature, I scoured the historical record for evidence of regular horse stables of the non-livery variety along East Bay Street. That search yielded the same result, however, as there were no stables of any kind directly on that busy commercial thoroughfare during the middle years of the nineteenth century. Again widening my criteria, I searched for privately-owned stables in the immediate vicinity of East Bay Street. South of Broad Street, there once stood several small stables behind various buildings facing both East Bay and Church Streets, and likewise, north of Broad Street, between East Bay and State Streets. Horses were not usually stabled on the wharves that once dominated the east side of East Bay, but there is evidence that a few were kept in this area during Robert Smalls’ tenure in Charleston.[5]

At this point in the research, I paused to evaluate my progress. The information I gleaned from various published biographies pointed to an Ancrum residence and to a stable, but my efforts to identify the location of those structures in urban Charleston produced only vague, inconclusive results. To advance my search, I needed to probe deeper into the biographical source material for clues that might help me refine the target and eliminate some of the potential candidates. I spent many hours reading books, articles, and websites devoted to the story of Robert Smalls with a more critical eye for detail. More specifically, I studied at the metadata—the footnotes and bibliographies in which historians reveal the sources they’ve consulted to construct their narratives. Peeling back the layers of scholarship to the primary source material, I sought to learn how Robert Smalls and/or his contemporaries described his Charleston residences. That’s when I discovered a major problem, a potential fatal flaw to sink this entire endeavor.

In the biographical literature published prior to 1958, I have not been able to locate any reference to the nature or location of Robert Smalls’ residence during his decade-long tenure in the City of Charleston. In materials published between 1958 and 2007, however, one finds repeated references to Smalls residing first with the Ancrum family, and later above a livery stable with his wife and children. The source material for these details, as cited by a number of reputable authors, is a book by Dorothy Sterling, published in 1958 under the title Captain of the Planter: The Story of Robert Smalls. Ms. Sterling’s source for this residential information was, it appears, the creative imagination of Ms. Dorothy Sterling.[6]

In her own bibliography, Ms. Sterling described Captain of the Planter as “a true story,” but it is not a work of historical scholarship. Rather, the book is indisputably a work of historical fiction. More precisely, it is what we might now call a young-adult novel, complete with fanciful illustrations. “In order to write the story in narrative form,” said Ms. Sterling in 1958, “some liberties have been taken in reconstructing conversations and in describing Lydia and Robert Smalls’ lives as slaves. Even these reconstructions, however, have been based on extensive research and are accurate in spirit if not in every detail.”[7] While much of the novel’s text does reflect Ms. Sterling’s research into the general history of American politics during the 1850s and the issues that led to the outbreak of Civil War, her intimate and highly romanticized descriptions of life in Charleston reflect a superficial and flawed understanding of the topography, geography, and culture within the city during that era.[8]

In her own bibliography, Ms. Sterling described Captain of the Planter as “a true story,” but it is not a work of historical scholarship. Rather, the book is indisputably a work of historical fiction. More precisely, it is what we might now call a young-adult novel, complete with fanciful illustrations. “In order to write the story in narrative form,” said Ms. Sterling in 1958, “some liberties have been taken in reconstructing conversations and in describing Lydia and Robert Smalls’ lives as slaves. Even these reconstructions, however, have been based on extensive research and are accurate in spirit if not in every detail.”[7] While much of the novel’s text does reflect Ms. Sterling’s research into the general history of American politics during the 1850s and the issues that led to the outbreak of Civil War, her intimate and highly romanticized descriptions of life in Charleston reflect a superficial and flawed understanding of the topography, geography, and culture within the city during that era.[8]

Dorothy Sterling bolstered the verisimilitude of her novel by acknowledging a debt to the youngest son of Robert Smalls: “The author would like to express particular appreciation to William Robert Smalls, who, in the course of two visits and dozens of letters, related all that he recalled of his father’s life and personality.”[9] William Robert Smalls (1892–1970) was born thirty years after his father’s famous escape from Charleston, however, and it’s unclear whether or not he possessed any knowledge of his father’s residence(s) in the Palmetto City prior to 1862. Without access to William’s letters to Ms. Sterling or transcripts of their conversations, I am unable to determine whether or not he was the source of Sterling’s descriptions of the Ancrum residence and/or the livery stable. Considering the absence of such details in the biographical literature about Robert Smalls published between 1862 and 1958, one might conclude that they were among the many colorful details invented by Dorothy Sterling for the purposes of her fictional narrative.

On the other hand, one could argue that Sterling’s imperfect 1958 references to an Ancrum residence and a livery stable might represent the distillation of authentic details, corrupted slightly by the passage of a century and relayed to the author in good faith by William Robert Smalls. As I described earlier, however, my efforts to identify an Ancrum townhouse in Charleston failed to locate a logical match, and the story of the livery stable on East Bay Street doesn’t match the landscape of that environment during the period in question. Even if there is a kernel of truth within Dorothy Sterling’s assertions, they’re simply too vague to lead us to a specific site.

So we’re back at square one: Where did Robert Smalls live in Charleston? During recent weeks, I’ve spent a lot of time reviewing the evidence and asking myself “are there any other clues or hints or patterns that might point the way to a more satisfying conclusion?” Brainstorming about alternative strategies led me to pursue several new research trajectories, each of which I’ll describe for the benefit of future researchers.

We know that Robert Smalls came to Charleston sometime around the year 1851, but the extant body of primary data articulates neither the precise timing nor the motivation behind this move. Historians have assumed it occurred around the time Henry McKee sold his residence in Beaufort, but details of that transaction disappeared when the Beaufort County Courthouse was destroyed by fire during the Civil War. While surviving evidence in Beaufort suggests that the McKee family simply removed to a new house within the same town around 1851, a number of historians have repeated an alternative story that Henry McKee sold his Beaufort home and removed his family and slaves to the Charleston area, where he purchased a plantation called “Cobcall.” This claim, first advanced in a 1904 article by J. Irving Washington, implies that Robert Smalls moved northward with his mother and might have resided near the city with Henry McKee.[10]

“Cobcall” is not a familiar name in the Charleston area, but I visited the Charleston County Register of Deeds to see if there was any record of Henry McKee purchasing a plantation in this vicinity around the year 1851. Paging through one of the oversized index books made during the nineteenth century, I quickly discovered that one John Henry McKee had purchased a four-hundred-acre tract called “Ship yard” plantation on Hobcaw Creek in Christ Church Parish in January 1852, and then in 1856 had purchased the adjoining “Rat Island,” also known as “D’Omblement.”[11] These properties, now within the town of Mount Pleasant and adjacent to the Wando River, are several miles from the City of Charleston, but the distance between them was easily traversed in the 1850s by long-established ferry routes that crossed the Cooper River many times each day (see Episode No. 68). Is it possible, therefore, that Robert Smalls could have taken the steamboat ferry from Mount Pleasant to Charleston to work on the city’s waterfront during his tenure in Charleston?

In a word, the answer is no. The John Henry McKee who purchased Shipyard plantation at Hobcaw Creek was a planter from the rural parish of St. Thomas, northeast of Charleston, not Henry McKee of the parish of St. Helena (Beaufort). The same John Henry McKee sold his Hobcaw plantation in 1853 and rented a house within urban Charleston, where he resided with his wife, four children, and seven enslaved people until he died in July 1860.[12] In short, there is no record of Henry McKee of Beaufort purchasing any property in the Charleston area around the middle of the nineteenth century. The 1904 story about “Cobcall” plantation is nothing more than a red herring in the biography of Robert Smalls. Its author, J. Irving Washington, could not have obtained such spurious information from Robert Smalls or his family, and this demonstrable fact undermines the credibility of the other colorful details about Small’s early life that appear only in Washington’s highly-romanticized 1904 article, and which have been repeated by many historians over the past century.[13]

In a word, the answer is no. The John Henry McKee who purchased Shipyard plantation at Hobcaw Creek was a planter from the rural parish of St. Thomas, northeast of Charleston, not Henry McKee of the parish of St. Helena (Beaufort). The same John Henry McKee sold his Hobcaw plantation in 1853 and rented a house within urban Charleston, where he resided with his wife, four children, and seven enslaved people until he died in July 1860.[12] In short, there is no record of Henry McKee of Beaufort purchasing any property in the Charleston area around the middle of the nineteenth century. The 1904 story about “Cobcall” plantation is nothing more than a red herring in the biography of Robert Smalls. Its author, J. Irving Washington, could not have obtained such spurious information from Robert Smalls or his family, and this demonstrable fact undermines the credibility of the other colorful details about Small’s early life that appear only in Washington’s highly-romanticized 1904 article, and which have been repeated by many historians over the past century.[13]

Although the story of Henry McKee of Beaufort owning a plantation near Charleston proved inaccurate, it inspired me to investigate whether or not there was any evidence that his family held any property within the Palmetto City. Henry McKee definitely inherited real estate from his father, but, owing to the loss of records during the Civil War, we don’t know the details of that property portfolio. I wondered if it was possible that Robert Smalls resided within a Charleston household that was owned by an absentee Henry McKee, which he had perhaps inherited from his late father. The index books at the Charleston County Register of Deeds office demonstrate that one John McKee purchased a number of properties in urban Charleston, near the city’s waterfront, during the early years of the nineteenth century. After his death, various executors managed the estate of John McKee through the 1850s, including a number of enslaved laborers distributed among various properties within urban Charleston. But the John McKee in question was a native of Ireland, a bricklayer by trade, who died in 1831, while John McKee of Beaufort, who owned Robert Smalls’ mother, died in 1834. Once again, this line of inquiry led to a red herring.

Having eliminated a number of fruitless leads, I’m at a loss for new ideas that might pinpoint a specific residence within urban Charleston. Rather than end this conversation on a low note, however, I’ll suggest an alternative tact. Perhaps the best path forward is the exploration of two old ideas. In the absence of any alternative data, I think it’s worth reconsidering both the story of the Ancrum family residence and the stable near the waterfront.

My investigation into the property holdings of James Hasell Ancrum II and his wife, Eliza Bold Ancrum, identified a number of addresses, but I did not delve deeply into the records to determine how the couple used each of the various properties. Information gleaned from census reports and city directories suggests that they moved house repeatedly during the 1840s and 1850s, and owned no real estate within the city by 1859, but a more thorough, in-depth biographical study of the Ancrums might reveal patterns and details relevant to the mystery of Robert Smalls’ residence. The first step in such a journey would be to determine if there is a sufficient volume of extant documents to facilitate such research. Even if one finds a mountain of Ancrum evidence, however, that line of inquiry might simply prove to be another red herring.

Similarly, I suspect that there is some grain of truth in the story of Robert and Hannah Smalls living above some sort of horse stable near the Charleston waterfront. As I mentioned earlier, there were no livery stables along either side of East Bay Street, but there were a number of small, private stables scattered between the Bay and Church and State Streets. Because we know Robert was employed on the wharves as a laborer, rigger, and seasonal boatman during the late 1850s, it’s entirely possible that he resided somewhere in this area. We can further refine this maritime neighborhood by noting that the vast majority of the waterfront activity in Charleston during the era of Robert Smalls’ tenure in the city took place between Stoll’s Alley to the south and Pinckney Street to the north. A number of small stables once stood in this area, so we can search for clues that might help us narrow the field of possibilities.

The existing biographical literature describing Smalls’ life in Charleston unanimously declares that Robert gained employment with a White stevedore and rigger named “John Simmons” around the year 1852 or 1853, and his first job was handling the horses used to hoist merchandise like cotton bales into and out of ships docked along the city’s various wharves. Although documentation proving this employment is lacking, the story is entirely plausible. John Symons (ca. 1815–1866), a native of England, was a well-established stevedore and rigger in Charleston by the time Robert Smalls arrived in the city.[14] Coincidently, Symons advertised in September 1852 that he “wanted to hire, by the month, or year, two men or boys, colored, to drive hoisting horses.”[15] Extant newspaper notices with specific addresses document his various moves across the urban landscape and his commercial partnerships with other riggers.[16] Surviving tax records also demonstrate that Symons owned a team of four horses during the late 1850s.[17] Property records show that he owned real estate on the south side of Pinckney Street, extending southward to the north side of Guignard Street. At No. 6 Guignard Street, just a stone’s throw from East Bay Street, Symons built a large rigging loft in 1854.[18]

The existing biographical literature describing Smalls’ life in Charleston unanimously declares that Robert gained employment with a White stevedore and rigger named “John Simmons” around the year 1852 or 1853, and his first job was handling the horses used to hoist merchandise like cotton bales into and out of ships docked along the city’s various wharves. Although documentation proving this employment is lacking, the story is entirely plausible. John Symons (ca. 1815–1866), a native of England, was a well-established stevedore and rigger in Charleston by the time Robert Smalls arrived in the city.[14] Coincidently, Symons advertised in September 1852 that he “wanted to hire, by the month, or year, two men or boys, colored, to drive hoisting horses.”[15] Extant newspaper notices with specific addresses document his various moves across the urban landscape and his commercial partnerships with other riggers.[16] Surviving tax records also demonstrate that Symons owned a team of four horses during the late 1850s.[17] Property records show that he owned real estate on the south side of Pinckney Street, extending southward to the north side of Guignard Street. At No. 6 Guignard Street, just a stone’s throw from East Bay Street, Symons built a large rigging loft in 1854.[18]

If Robert Smalls worked for John Symons during the busy winters between 1852 and 1861, and if Robert and Hannah did in fact rent rooms above a stable or a similar structure during the last five years of their tenure in Charleston, it seems logical to identify John Symons as the person most likely to have rented said rooms to the Smalls. Symons worked with other men in the city who also owned rigging lofts and kept horses near the waterfront, so it’s also possible that he directed Robert to rent rooms above another man’s stable. If I had to make a wager on this question, however, I’d bet on John Symons as the strongest candidate.

Further research is needed to refine our knowledge of Symon’s property between Guignard and Pinckney Streets, but I feel comfortable in directing our collective gaze to that location. In the meantime, I’ll leave you with this qualified conclusion:

Further research is needed to refine our knowledge of Symon’s property between Guignard and Pinckney Streets, but I feel comfortable in directing our collective gaze to that location. In the meantime, I’ll leave you with this qualified conclusion:

Owing to the nature of the known documentary evidence relating to Robert Smalls’ tenure in Charleston, it is not currently possible to positively identify the precise location of his residence(s) within the city during the years preceding his famous escape with the Planter in 1862. Considering the sparse clues and circumstantial evidence drawn from the body of historiography, however, it is plausible to conclude that Smalls might have lived for some time above a stable or rigging loft belonging to his employer, John Symons, on the north side of Guignard Street, very near the present horse barn of Palmetto Carriage Works.

This statement does not represent the last word on the subject. My research into Robert Smalls’ tenure in Charleston has eliminated a few spurious leads, and I hope other scholars will continue to engage with the available documentary resources and refine this important story. As we commemorate the anniversary of the escape of the Planter in May 1862, I encourage everyone to stroll along Charleston’s popular East Bay Street to the less familiar but equally historic Guignard Street. There, among the sounds of modern hoof beats and jingling carriage traces, a bit of old Charleston once familiar to Robert Smalls still exists.

[1] Anyone interested in learning more about Robert Smalls’ work on the Charleston waterfront will benefit from reading Michael D. Thompson’s excellent monograph, Working on the Dock of the Bay: Labor and Enterprise in an Antebellum Southern Port (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2015).

[2] In a speech to the “Freedmen’ Society” of New York in the early autumn of 1862, Robert Smalls allegedly stated that the plan to steal the Planter arose during a meeting “at my house.” See Charleston Mercury, 30 September 1862, page 2, “The Running off of the Steamer Planter from Charleston.”

[3] To my knowledge, Robert Smalls never directly addressed this topic in any surviving documentary source. The questions posed to Smalls during an 1873 interview focused on misogynistic questions about African-American women. See John W. Blassingame, ed., Slave Testimony: Two Centuries of Letters, Speeches, Interviews, and Autobiographies (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1977), 373–79.

[4] Note that in 1859 and 1860, J. H. Ancrum paid taxes on a number of slaves residing within the City of Charleston, but did not pay taxes on any real estate within this city. See City of Charleston, List of the Tax Payers of the City of Charleston, for 1859 (Charleston, S.C.: Walker, Evans & Co., 1860), 10; City of Charleston, List of the Tax Payers of the City of Charleston, for 1860 (Charleston, S.C.: Evans & Cogswell, 1861), 9.

[5] Thomas Cumming, for example, owned a rigging loft and stable on his property at the northeast corner of East Bay and Pritchard Street in the 1840s and early 1850s, which was advertised for rent in Charleston Courier, 22 December 1854, page 3.

[6] See, for example, Dorothy Sterling, Captain of the Planter: The Story of Robert Smalls (New York: Doubleday, 1958), 37–38, 47; Okon Edet Uya, From Servitude to Service: Robert Smalls, 1839–1915 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), 5–13; Edward A. Miller, Gullah Statesman: Robert Smalls from Slavery to Congress, 1839–1915 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1995), 8–9; and Andrew Billingsley, Yearning to Breathe Free: Robert Smalls of South Carolina and His Families (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2007), 34–35, 44–45. Note that Cate Lineberry, Be Free or Die: The Amazing Story of Robert Smalls’ Escape from Slavery to Union Hero (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2017), 44, 47, states that Smalls “likely lived in the slave quarters at the house of Eliza Ancrum,” but did not repeat Sterling’s story about the livery stable.

[7] Sterling, Captain of the Planter, 247.

[8] A list of Charleston-specific errors found within Captain of the Planter—and repeated by later writers—would fill many pages; readers, scholars, and film producers are respectfully advised to exercise caution before embracing that portion of Sterling’s text as fact.

[9] Sterling, Captain of the Planter, 247.

[10] J. I. [Irving] Washington Sr., “General Robert Smalls,” The Colored American Magazine 7 (June 1904), 424. Washington’s story about the McKee family’s removal to “Cobcall” is discussed in Uya, From Servitude to Service, 5; Miller, Gullah Statesman, 8, described “Cobcall” as a plantation “near Georgetown.”

[11] Edward W. LaRoche, planter, to John Henry McKee, planter, conveyance of “Shipyard at Hobcaw,” 3 January 1852, Charleston County Register of Deeds (hereafter RoD), Book O12: 541–42; John H. McKee to Edward LaRoche, mortgage of “Ship Yard at Hobcaw,” 3 January 1852, RoD P12: 577–78; John H. McKee to Robert M. Muirhead, conveyance of “Ship Yard at Hobcaw,” 30 November 1853, RoD A13: 439–40; Irvine Keith Furman, physician of the parish of St. Thomas, to John H. McKee, “of the said parish,” planter, conveyance of “‘D’Omblement’ or ‘Rat Island,’” 29 January 1856, RoD X13: 270; John H. McKee to Charles M. Furman, conveyance of “‘D’Omblement’ or ‘Rat Island,’” 28 February 1860, RoD R14: 156.

[12] The household of J. H. McKee appears in the 1860 U.S. Census (enumerated on 16 June) and the 1860 U.S. Schedule of Slave Inhabitants (dated “June 1860”) in Ward 7 of the City of Charleston. According to the weekly “Return of Deaths within the City of Charleston,” now held at the Charleston Archive at the Charleston County Public Library, a 32-year-old white male named John H. McKee died in Charleston on 8 July 1860.

[13] How did J. Irving Washington learn about the McKee plantation that he called “Cobcall”? If Washington had personally visited the deed office to search for McKee properties, he would have learned the correct spelling of “Hobcaw.” I suspect someone communicated this information to Washington verbally, and he corrupted the spelling to “Cobcall.” Mr. Washington, of New York City, likely met a person who had formerly resided in the Charleston area and who mentioned to him that a man named McKee had owned a plantation at Hobcaw near the city in the years before the Civil War.

[14] According to Brent Holcomb, ed., South Carolina Naturalizations 1783–1850 (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1985), 33, one John Symons, a carpenter from Northumberland, England, was naturalized in Charleston on 29 August 1838. This may have been an older relative of the stevedore and rigger of the same name. John Symons, “born at No. 1 Tavistock Terrace, Plymouth, County of Devonshire, England,” made his will at Mount Pleasant on 8 November 1865, which was proved in Charleston on 6 September 1866; see WPA transcript volume 51: 586–87, in the South Carolina History Room at CCPL.

[15] Charleston Courier, 22 September 1852, page 3. Symons, “rigger and stevedore,” gave his address as 44 Tradd Street (which is not the same property as the present 44 Tradd Street).

[16] See, for example, Symons’ notices in Charleston Courier, 12 September 1853, page 3; 1 December 1857, page 3; 1 January 1858, page 3; 17 June 1861, page 2.

[17] According to City of Charleston, List of the Tax Payers of the City of Charleston, for 1859 (Charleston, S.C.: Walker, Evans & Co., 1860), 334, John Symmons [Symons] paid tax on real estate valued at $6,500 and on 4 horses; according to City of Charleston, List of the Tax Payers of the City of Charleston, for 1860 (Charleston, S.C.: Evans & Cogswell, 1861), 275, John Symons paid tax on real estate valued at $5,500 and on 4 horses.

[18] A description of Symons’ rigging loft appears in the proceedings of the Charleston City Council meeting of 14 March 1854, which were printed in Charleston Courier, 16 March 1854, page 4: “Notice from John Symons, rigger and stevedore, of his intention to erect a rigging loft 80 feet long, 20 feet wide, and 16 feet high on brick pillars, the roof to be covered with tin, at No. 6 Guignard Street. Referred to the Committee on Wooden Buildings.” Symon’s owned a 40-foot-wide lot that stretched from the north side of Guignard Street to the south side of Pinckney Street; see City of Charleston, Property Tax Assessments, 1852–56, Ward 3, pages 19 and 42, in the Charleston Archive at CCPL.

NEXT: Oqui Adair: First Chinese Resident of South Carolina, Part 1

PREVIOUSLY: Creating a Walled City: The Charleston Enceinte of 1704

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments