Creating a Walled City: The Charleston Enceinte of 1704

Processing Request

Processing Request

Fearing a Spanish attack on the capital of South Carolina in 1704, English and French colonists directed enslaved Africans to excavate many tons of earth to create a moat and earthen wall around Charleston. This continuous line of entrenchment, stretching nearly a mile in length, included numerous cannon placed within bastions and redans, while a single gateway with drawbridges controlled access into and out of the town. The defensive works of 1704 transformed Charleston into an “enceinte” or enclosed settlement of just sixty-two acres that restricted the community’s growth for decades.

Today’s program is a continuation of the story line I started in Episode No. 221. In that program, we talked about the political and military context of 1703 that motivated the South Carolina General Assembly to order the construction of an earthen wall and moat around a portion of urban Charleston. The commencement of a new war between England, France, and Spain in 1702 had triggered a wave of anxiety in South Carolina, primarily because of the proximity of Spanish neighbors in Florida. After Spanish forces from Cuba annihilated the small English settlement at Nassau in the Bahamas, the people of Charleston feared the Carolina capital might form their next target.

Governor Nathaniel Johnson called the South Carolina General Assembly for an emergency session in early December 1703 to formulate a defensive strategy. During two weeks of intensive work, the provincial government adopted a fortification plan drawn by a French immigrant named Samuel DuBourdieu, and engaged the services of another Frenchman, Jacques Le Grande, Sieur de Lomboy (aka James Lomboy), to help the government transfer DuBourdieu’s scaled plan onto the full-sized landscape of the town. On December 23, the South Carolina legislature ratified an act ordering the construction of new fortifications to envelop the core real estate of urban Charleston and appointed Colonel William Rhett to act as sole commissioner or “manager” of the project.

The fortification act of December 1703 initiated the creation of an “enceinte” or fortified enclosure that encompassed the highest and driest real estate within the colonial capital of South Carolina. This enceinte was not a monolithic structure, but rather a chain of interconnected structures, including several bastions, redans, and one ravelin, all of which were linked by straight curtain walls. Three sides of this enceinte—to the south, west, and north of the town—were built of earth and wood in 1704, while the long waterfront side was composed of brickwork that had commenced several years earlier and continued beyond 1704.

The fortification act of December 1703 initiated the creation of an “enceinte” or fortified enclosure that encompassed the highest and driest real estate within the colonial capital of South Carolina. This enceinte was not a monolithic structure, but rather a chain of interconnected structures, including several bastions, redans, and one ravelin, all of which were linked by straight curtain walls. Three sides of this enceinte—to the south, west, and north of the town—were built of earth and wood in 1704, while the long waterfront side was composed of brickwork that had commenced several years earlier and continued beyond 1704.

This difference in material is important because the provincial government assigned different priorities to each. The provincial government ordered the creation of the enceinte in response to what it considered a defensive emergency. At the beginning of 1704, local officials paused the unfinished brickwork along Charleston’s eastern waterfront and pivoted all available labor and resources to complete the task of enclosing the core of the town within a circuit of defensive works. As I described in Episode No. 221, the walls built around urban Charleston in 1704 were entrenchments—hastily-constructed defensive works composed of cheap, readily-available materials to address an emergency situation. Workers excavated a ditch or moat and piled the earth on the adjacent surface to construct a defensive barrier. These entrenchments were designed to last for a few years, after which the inhabitants might scrape the earthen walls back into the adjacent moat without altering the landscape in a permanent manner. The fact that it is now very difficult to find any trace of these early walls is a testament to the success of the emergency plan adopted by the South Carolina General Assembly in late 1703.

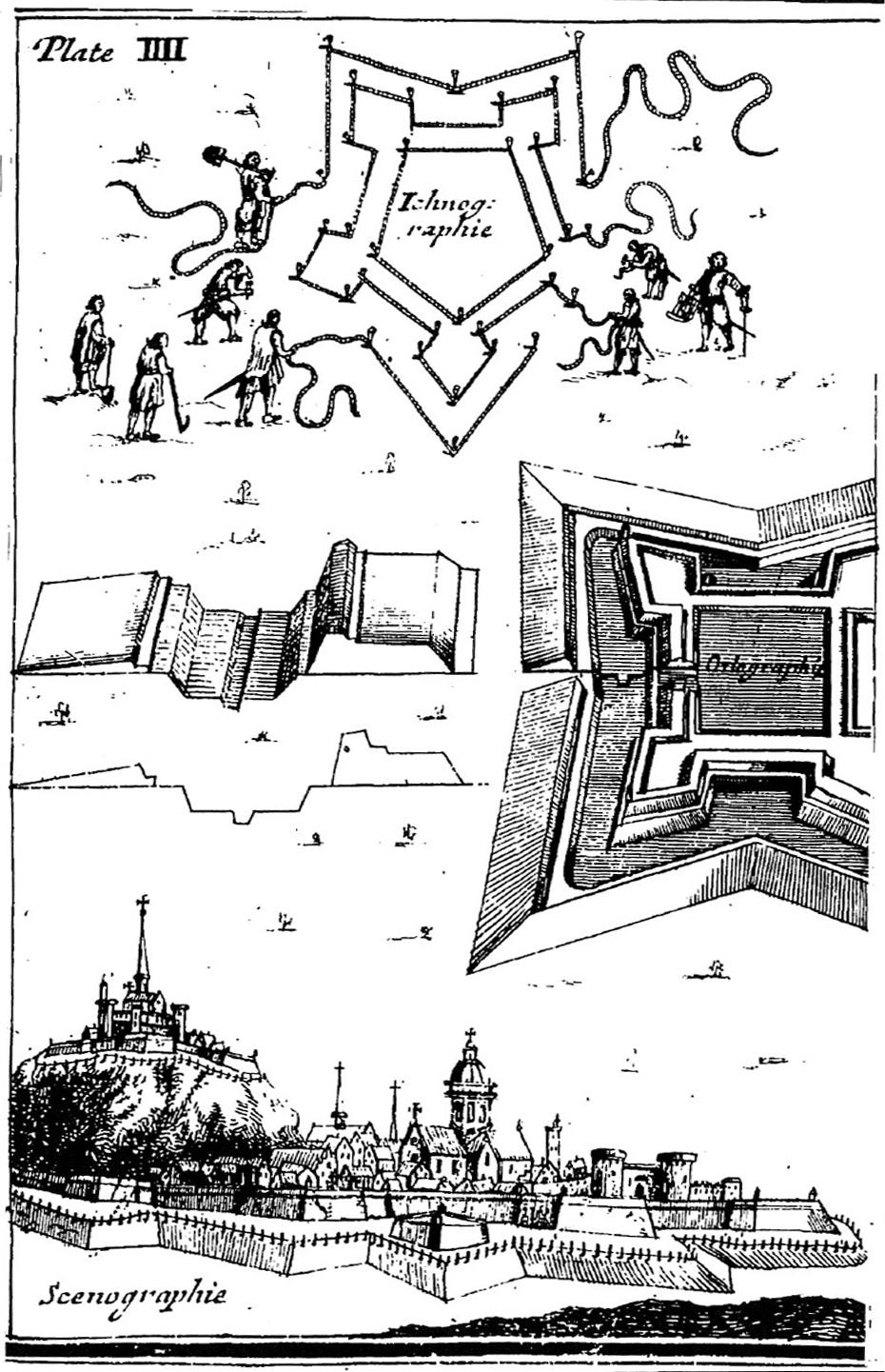

Huguenot immigrant James Lomboy began assisting the provincial government with their fortification plans during the third week of December 1703, but his main contributions commenced in the days after the legislature adjourned for the Christmas holiday. His first task would have been to procure a number of long ropes—the sort of maritime cordage readily available in any port town of that era—to create an outline of the ditch and the walls on the surface of the ground along the proposed path of the works. Numerous fortification textbooks published in Europe during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century describe the use of ropes to perform this preliminary step, so we might assume that Monsieur Lomboy did likewise. The lines of the ropes, augmented by wooden stakes driven at intervals, provided laborers and supervisors with clear visual guides for the digging and piling to be done.

James Lomboy did not leave behind a journal of his labors in 1703–4, but we can construct a hypothetical narrative of his work by visualizing the landscape of urban Charleston at that time. This task is simplified by the existence of a smattering of documentary clues, notes from recent physical explorations, and three contemporary or nearly-contemporary illustrations. This essay includes images of the well-known Crisp Map of 1711 and John Herbert’s lesser-known plan of the fortifications of Charleston, drafted in the autumn of 1721.[1] These two illustrations depict slightly different and stylized versions of the enceinte surrounding the town, but they provide invaluable visual clues. Herbert’s hand-drawn plan, for example, indicates that the enceinte enclosed just sixty-two acres at the core of urban Charleston. Bishop Roberts traced the outline of the fortified enceinte on his 1739 map titled Ichnography of Charleston at High Water, but that image was created several years after the town’s earthen walls and surrounding ditch had been demolished, and might not provide an entirely reliable visual representation.[2]

James Lomboy did not leave behind a journal of his labors in 1703–4, but we can construct a hypothetical narrative of his work by visualizing the landscape of urban Charleston at that time. This task is simplified by the existence of a smattering of documentary clues, notes from recent physical explorations, and three contemporary or nearly-contemporary illustrations. This essay includes images of the well-known Crisp Map of 1711 and John Herbert’s lesser-known plan of the fortifications of Charleston, drafted in the autumn of 1721.[1] These two illustrations depict slightly different and stylized versions of the enceinte surrounding the town, but they provide invaluable visual clues. Herbert’s hand-drawn plan, for example, indicates that the enceinte enclosed just sixty-two acres at the core of urban Charleston. Bishop Roberts traced the outline of the fortified enceinte on his 1739 map titled Ichnography of Charleston at High Water, but that image was created several years after the town’s earthen walls and surrounding ditch had been demolished, and might not provide an entirely reliable visual representation.[2]

These three historical images identify several particular parts of Charleston’s early fortifications with proper names, but it’s important to remember that these names appeared several years after the structures were created. None of the features described in this program had a distinctive name in 1704, but extant legislative records demonstrate that locals had named the town’s five bastions by the end of 1708, and those names continued to be used for as long as the structures remained in use.[3] For the purposes of identifying the structures constructed around 1704, therefore, we’ll use the names that appear in later records.

The fortifications standing in Charleston in December 1703 included an unfinished brick wall along the east side of modern East Bay Street, including a finished Half-Moon Battery at the east end of Broad Street, and an unfinished brick fort at the south end of the Bay Street. Monsieur Lomboy almost certainly commenced his efforts to outline the proposed entrenchments at the northwestern point of the unfinished fort that later became known as Granville Bastion. A brick wall extending from the northwest corner of Granville Bastion followed a west-northwesterly trajectory for approximately 100 feet (the path of which is accurately marked in the private driveway of No. 43 East Bay Street).[4] That brickwork terminated at the edge of high ground adjacent to a watery inlet that once flowed from the Cooper River towards Church Street along a northwesterly path.

The fortifications standing in Charleston in December 1703 included an unfinished brick wall along the east side of modern East Bay Street, including a finished Half-Moon Battery at the east end of Broad Street, and an unfinished brick fort at the south end of the Bay Street. Monsieur Lomboy almost certainly commenced his efforts to outline the proposed entrenchments at the northwestern point of the unfinished fort that later became known as Granville Bastion. A brick wall extending from the northwest corner of Granville Bastion followed a west-northwesterly trajectory for approximately 100 feet (the path of which is accurately marked in the private driveway of No. 43 East Bay Street).[4] That brickwork terminated at the edge of high ground adjacent to a watery inlet that once flowed from the Cooper River towards Church Street along a northwesterly path.

The line of entrenchment created in 1704 could have continued in a northwesterly direction from the end of the aforementioned brick wall to the “back” part of the town, but that trajectory would have placed the new fortifications within a few feet of the Baptist Church near the southwestern end of Church Street. To avoid such an encroachment, the legislature, in consultation with James Lomboy on December 21st, 1703, agreed to deflect the line of the new works southward. To better defend the now-irregular angle of the town’s southern defensive line of entrenchment, Lomboy proposed to build an additional gun battery that was not specified in Samuel DuBourdieu’s original plan.

From the western end of the aforementioned brick wall (now in the driveway of No. 43 East Bay Street), the line traced by James Lomboy turned to the southwest at an angle of approximately 22.5 degrees, and continued as a row (or perhaps double row) of pilings or palisade leading in a southwesterly direction nearly 200 feet towards the opposite side of the inlet.[5] The muddy inlet formed a kind of natural barrier, so it did not require the excavation of a ditch; thus there was no wall along this part of the town. In fact, the provincial government agreed in November 1704 to build a pedestrian bridge across the inlet, behind the palisade wall and “within the fortifications.”[6]

At the high ground on the southwestern side of the aforementioned inlet (now the north side of Water Street), James Lomboy used his ropes to outline an irregularly-shaped gun battery that became known as Ashley Bastion. This structure, of unknown dimensions, occupied part or all of the lots presently identified as 8, 10, and 12 Water Street. An inventory of the artillery distributed around Charleston in October 1704 noted the presence of three medium-sized cannon called sakers at this bastion, as well as two smaller cannon called minions, which the provincial government planned to replace with an additional pair of sakers.[7]

The curtain line of the entrenchment created in 1704 commenced properly, therefore, from the northwestern edge of Ashley Bastion and continued along a northwestward path approximately 900 feet towards the intersection of Meeting and Tradd Streets. Recent exploration along this route using ground-penetrating radar suggests that this line of ditch and earthen wall followed a trajectory that is approximately 57.5 degrees west of present north, or a heading of 302.5 degrees on the compass.[8]

In the center of this stretch of the town’s southern line of entrenchment, slightly west of Church Street, Monsieur Lomboy outlined a redan—a V-shaped structure sometimes called a “salient angle,” that projected outward from the main line of fortification and thereby enabled defenders to fire shots at any attackers who might traverse the ditch and attempt to scale the walls. The aforementioned artillery inventory of October 1704 noted the presence of two minions at this redan, which the government hoped to exchange for two sakers. The precise dimensions of this redan are currently unknown, as it was scraped off the surface of the earth three centuries ago and the site is now covered with buildings both old and new.

At the southwest corner of the intersection of Meeting and Tradd Streets, where Second Presbyterian Church now stands, Lomboy outlined a large bastion of unknown dimensions that formed the southwest corner of the enceinte. A bastion is a four-sided structure usually found projecting outward from the corners of large fortifications, in which defenders traditionally placed multiple cannon. The artillery inventory of 1704 indicates that this bastion, which became known as Colleton Bastion, was equipped with two sakers and five minions, but the local government planned to replace this armament with four sakers and two minions.

From the northeast corner of Colleton Bastion, the western curtain line of the 1704 entrenchment continued northward along a path parallel to that of Meeting Street, but surviving government records from that era do not articulate the physical relationship between the two entities. Despite this archival silence, several contemporary illustrations provide useful clues. The original core of Meeting Street, stretching between White Point Garden and Beaufain Street, has been sixty-six feet wide (or one surveyor’s chain) since it was established in the so-called “Grand Model” of Charleston in the 1670s.[9] In contrast to this generous breadth, however, both the Crisp map of 1711 and the Herbert plan of 1721 depict Meeting Street as a rather narrow thoroughfare, while the 1739 Ichnography of Charles Town shows the former line of entrenchments straddling the western half of Meeting Street. The similarity of these three depictions suggests that James Lomboy, in consultation with local officials in the winter of 1703–4, usurped the western half of Meeting Street between Tradd Street and Horlbeck Alley for defensive purposes. This decision to constrict the street’s width likely reflects a compromise between the need for a public thoroughfare in this area and the government’s effort to encroach as little as possible on private property to the west of the public street. For at least two decades after Mr. Lomboy’s work, therefore, Meeting Street was roughly the same size as Tradd and Queen Streets; that is, thirty-three feet wide, or one-half of a surveyor’s chain.

From Colleton Bastion, the curtain line of entrenchment continued northward along the western half of Meeting Street for nearly two hundred and fifty feet. At this point, Monsieur Lomboy outlined another small redan at the approximate location of the present Nos. 65–67 Meeting Street. Like the previous redan, this southwestern redan was armed with a pair of minions in the autumn of 1704. The line of entrenchment then continued northward a further distance of approximately two hundred and fifty feet to the site now occupied by the Federal Post Office at the southwest corner of Meeting and Broad Streets.

The intersection of Meeting and Broad Street was designed in the 1670s as the principal crossing or “Market Square” of urban Charleston. In the entrenchment campaign of 1703–4, this intersection was reshaped to serve as the principal gateway into and out of the fortified town. Beginning from a point on the west side of Meeting Street, slightly south of Broad Street, James Lomboy outlined a large fortified triangle that extended northward to a point slightly beyond Broad Street, near the northeastern corner of the old South Carolina State House that is now the Charleston County Courthouse. This triangle projected westward to a point in the center of Meeting Street, but its precise dimensions are not yet known. It was either an equilateral or isosceles triangle, and might have extended from the middle of Meeting Street to a point near the western edge of the historic courthouse.

Beginning with the outline of a large triangle at the intersection of Meeting and Broad Streets, workers transformed this site into a fortified structure defended by two cannon, known in the vocabulary of military architecture as a ravelin. Charleston’s ravelin of 1704, like those found at hundreds of fortified sites around the world, was essentially a detached, fortified island designed to control access into and out of the enceinte. Because the ditch or moat created in 1704 initially surrounded Charleston’s ravelin, travelers wishing to enter or exit the town had to traverse a pair of drawbridges—one near the center of the intersection of Meeting and Broad Streets, and a second on the northwestern flank of the triangle, under the center of the present Charleston County Courthouse. By the time John Herbert drew his plan of the town’s fortifications in 1721, however, locals had apparently filled the ditch along the ravelin’s eastern line and removed the drawbridge from the center of the intersection. Let’s postpone a deeper dive into the architectural details of this ravelin for the moment and continue our tour of the 1704 entrenchments.

Beginning with the outline of a large triangle at the intersection of Meeting and Broad Streets, workers transformed this site into a fortified structure defended by two cannon, known in the vocabulary of military architecture as a ravelin. Charleston’s ravelin of 1704, like those found at hundreds of fortified sites around the world, was essentially a detached, fortified island designed to control access into and out of the enceinte. Because the ditch or moat created in 1704 initially surrounded Charleston’s ravelin, travelers wishing to enter or exit the town had to traverse a pair of drawbridges—one near the center of the intersection of Meeting and Broad Streets, and a second on the northwestern flank of the triangle, under the center of the present Charleston County Courthouse. By the time John Herbert drew his plan of the town’s fortifications in 1721, however, locals had apparently filled the ditch along the ravelin’s eastern line and removed the drawbridge from the center of the intersection. Let’s postpone a deeper dive into the architectural details of this ravelin for the moment and continue our tour of the 1704 entrenchments.

From the northeastern corner of the ravelin, the line of entrenchment progressed northward along the western half of Meeting Street for approximately 400 feet to a third redan, armed with two minions, that probably straddled the present intersection with Queen Street.[10] Continuing northward a further four hundred-odd feet, James Lomboy outlined another corner bastion, later called Carteret Bastion, near the intersection of Meeting Street and Horlbeck Alley. The 1704 inventory of artillery noted the presence of six “small guns” at this bastion, but, like Colleton Bastion, the government planned to furnish Carteret Bastion with four sakers and two minions.

Construction projects around the intersection of Meeting and Horlbeck Alley and Cumberland Street in recent decades have provided a few opportunities to search for traces of Carteret Bastion, but its precise location remains elusive.[11] We know, however, that the presence of a large tidal inlet extending westward through modern Market Street, formerly known as Daniel’s Creek, discouraged the fortification planners of 1703–4 from extending the entrenchments northward beyond the point now marked by Horlbeck Alley. Furthermore, the known angle of the northern line of the town enceinte, which we’ll discuss in a moment, suggests that Carteret Bastion likely stood at the southwest corner of the modern intersection of Meeting Street and Horlbeck Alley.

From the northeast corner of Carteret Bastion, the line of entrenchments created in 1704 turned to the northeast and continued for approximately 1,400 feet to a brick bastion, later called Craven Bastion, that once stood at the southeast corner of modern East Bay and Market Streets. No trace of this line now exists, but a 1750 plat of property at the southeast end of modern Market Street specifies the precise orientation of this “old fortification line.” The plat indicates that the northern line of the Charleston enceinte of 1704 followed a path that was 62 degrees west of south at that time, or a heading of 242 degrees on the compass.[12] To visualize that angle, take a look at the 300-year-old Powder Magazine on the south side of Cumberland Street. The magazine was built in 1712–13, thirty-five years before the creation of Cumberland Street, and its massive brick walls were oriented to be parallel to the nearby line of entrenchment. In fact, the provincial government’s 1712 plan to build the magazine specified that it should be built “within twenty yards of the redoubt [that is, redan] on the north part of Charles Town.”[13]

Along the northern line of the 1704 enceinte, James Lomboy outlined two redans that divided the line into three roughly-equal segments. The westernmost of the two redans stood slightly to the east of the Powder Magazine and is now under the parking garage on the north side of Cumberland Street. The easternmost redan of the town’s northern line is very likely under the new hotel standing at the southwest corner of State and Linguard Streets. The aforementioned artillery inventory of October 1704 did not include either of these redans, and it’s unclear whether they were ever equipped with cannon.

The final bastion in our tour of the Charleston enceinte of 1704 stood at the southeast corner of modern East Bay and Market Streets, on the site now occupied by the U.S. Customs House, and was known as Craven Bastion by the end of 1708. Although this structure completed the circuit of the fortifications that surrounded Charleston in the early years of the eighteenth century, it was perhaps the last component built. The fortification act of December 1703 that initiated the entrenchment project also ordered the construction of a brick “battery” at this site, but the artillery inventory of October 1704 noted that construction of what became Craven Bastion had not yet commenced.

The final bastion in our tour of the Charleston enceinte of 1704 stood at the southeast corner of modern East Bay and Market Streets, on the site now occupied by the U.S. Customs House, and was known as Craven Bastion by the end of 1708. Although this structure completed the circuit of the fortifications that surrounded Charleston in the early years of the eighteenth century, it was perhaps the last component built. The fortification act of December 1703 that initiated the entrenchment project also ordered the construction of a brick “battery” at this site, but the artillery inventory of October 1704 noted that construction of what became Craven Bastion had not yet commenced.

The construction of Craven Bastion, like the rest of the brick fortifications built along the east side of East Bay Street around the turn of the eighteenth century, forms part of a separate narrative that I’ll defer to a future program. A few very interesting conversations about that brickwork took place in the provincial legislature during the course of the year 1704, but we’ll ignore that historical rabbit hole for the moment and return to our focus to the new entrenchments that surrounded the south, west, and north sides of the town.[14]

After James Lomboy laid out a series of ropes and stakes to outline the new fortifications, William Rhett, the general manager of the project, hired unidentified White men to act as overseers or foremen of the enslaved laborers who performed the majority of the work. The fortification act of December 1703 empowered Rhett to impress or commandeer “any negroes within the limits aforesaid [that is, within the area encompassed by the entrenchments], to worke, at the rate of two royalls [Spanish reales] and a halfe per diem, their masters finding them victualls.” Rhett was empowered to pay the enslaved men three reales if “the said negroes are tradesmen.” To supervise the enslaved labor force, the law empowered Rhett to impress “white men for overseers, within the precincts aforesaid, at the rate of two shillings and six pence per diem, they finding themselves victualls,” as well as “negros, horses and carts, at five shillings per diem, and tooles, [such] as spades, howes, pick-axes, and all other tools and utensels fitting for the carrying on the said worke; and shall also have the power to cut down any pine timber off and from any plantation or tract of land for the said worke.”[15]

Neither William Rhett nor any other official involved in this massive public works project recorded a timeline of their work, and financial accounts that might detail the number and identities of the laborers have long since disappeared. Despite these archival shortcomings, we can use a few extant clues to conclude that the work of excavating a continuous ditch around the perimeter of urban Charleston and shaping that earth into a chain of interconnected structures occupied scores of laborers over a period of many months.

The South Carolina General Assembly met only briefly during the spring of 1704, but reconvened for a longer session that autumn. On October 5th, Governor Nathaniel Johnson stood before the assembly and congratulated them for a year of fruitful industry. “Att a former meeting of this Assembly” (in December 1703), said the governor, “I proposed to you the fortifying of Charles Towne. Soe great a progress hath been made in that work, that the intrechments are, in a great measure perfected.” The stout earthen walls surrounding Charleston protected the town from enemy attack, but they formed a nuisance to some inhabitants and recreational facilities to others. Besides the Bay street waterfront, facing the Cooper River, there was now but a single gateway into and out of the town that every person and animal was obliged to use. Governor Johnson observed to the legislature that “several person having, lately, presumed to climb over the intrenchments, which, if suffered will in a little time, deface and break down the same; I think it proper to propose to your consideration the taking of some measures to prevent it.”[16]

One month later, on November 4th, 1704, the South Carolina General Assembly ratified “An Act to prevent the breaking down and defacing the Fortifications in Charles Town.” The law’s preamble noted the provincial government had fortified the capital “with intrenchments and other works, to make it defensible in this time of war and danger of an invasion from our enemies.” Despite the “great charge, expence, and labor” of that work, however, “some inconsiderate or evil disposed persons, not regarding or minding the evil consequences of defacing and breaking down the said fortifications, do presume to climb and get over the said intrenchments and other works, and so break them down, and lay open the said town.” Therefore, “to prevent such mischief for the future,” the general assembly established a fine of twenty shillings on “any white person or persons, above the age of sixteen,” who “shall presume or endeavour to climb or pass over any part of the said fortifications, inward or outward of Charlestown, or go down into the ditch or trench.”

White persons who did not immediately pay the fine would receive fifteen lashes on the bare back “at the public stocks,” then located at the east end of Broad Street, followed by another fifteen lashes “at the inward bridge” (that is, at the gate of the inner drawbridge leading from the intersection of Meeting and Broad Streets to the ravelin). Enslaved people who were convicted of climbing on the entrenchment would simply be “whipped round the town” if their respective masters did not pay the fine aforementioned.

Another paragraph extended the 1704 law to Charleston’s youngest inhabitants, complaining that “children under the age of sixteen have and do daily deface the said fortifications, by passing and going over them.” To discourage this recreational practice, the law required the parents and guardians to “correct” such trespassing children; if they refused or neglect to punish their own children, then the law empowered and required local officials “to cause as aforesaid such correction [that is, whipping] to be given to the said child or children, as he shall think fit, not exceeding twenty lashes.”

Another paragraph extended the 1704 law to Charleston’s youngest inhabitants, complaining that “children under the age of sixteen have and do daily deface the said fortifications, by passing and going over them.” To discourage this recreational practice, the law required the parents and guardians to “correct” such trespassing children; if they refused or neglect to punish their own children, then the law empowered and required local officials “to cause as aforesaid such correction [that is, whipping] to be given to the said child or children, as he shall think fit, not exceeding twenty lashes.”

The new law also prohibited cattle from roaming around the town within the line of the entrenchments. Henceforth, anyone keeping a “mare, colt, cow, calf, or ox, or any other cattle” within the town was obliged to keep such animals “inclosed in their own lots.” Horses in general, except mares and colts, were specifically exempt from this requirement, however. To ensure that hooved animals did not wander in and out of the enceinte, the law to protect the new fortifications empowered the governor or chief militia officers within the capital “to appoint a centinel at the gate and bridge, to be paid out of the public treasury, not exceeding ten pounds per annum,” who will “keep out of the aforesaid intrenchments [that is, out of the town] all the cattle above mentioned; and if any of the said cattle doth get into the said intrenchments through the gates, the said centinel shall immediately on notice thereof, drive out of the said intrenchments the said cattle” or pay a fine for failing to do so.[17]

Another act ratified on the same day in November 1704 created a novel zoning restriction within the enceinte formed by the new fortifications: “Forasmuch, as by dung and filth of the garbage and intrails of beasts, and the scalding of swine, killed in slaughter houses and yards within the intrenchments, the air is greatly corrupted and infected, and many maladies and other intolerable diseases do daily happen, as well to the inhabitants as strangers and travelers, in and out of Charlestown,” the government declared that henceforth “no butcher, or any other person or persons whatsoever, shall kill any cattle, sheep or hoggs, nor use or erect any slaughter house, cattle penn, sheep penn, or hogg sties, in either streets or yards within the intrenchments of Charles Town.”[18]

At the end of its legislative session in November 1704, the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly settled two financial matters that provide important clues for understanding the “walled city” of early Charleston. On November 6th, the Commons House ordered Colonel William Rhett to draw £729.12.3 (probably calculated in English sterling) “being so much indebted to several persons for materials and work, and fortifying Charlestown.” The discussion of this sum was distinct from a similar conversation about the unfinished brickwork on East Bay Street, so we might conclude that it related solely to labor, tools, and materials used to construct the entrenchments on the south, west, and north parts of the town.[19] That figure of more than £729 was certainly a significant amount of money to be drawn from the public treasury, but it was just a fraction of the ongoing cost of the brickwork along Charleston’s Bay Street.

Also on 6 November 1704, the Commons House ordered the public treasurer of South Carolina to pay £100 “unto Mr. James De Longboys . . . for his care and industry in laying out and carrying on the fortifications of Charlestown, and for his expenses in attending thereon.” Furthermore, the House appropriated an additional £50 to be paid to Monsieur Lomboy “at the finishing of the Intrenchments and Batteries of the said Fortifications.”[20] This total of £150 represents a significant sum of money at that time, and therefore suggests that Jacques Le Grande, Sieur de Lomboy, played an important role in directing and shaping the construction of the Charleston enceinte of 1704.

Owing to the watery inlets along the south and north sides of urban Charleston at the beginning of the eighteenth century, the lines of the 1704 enceinte formed an irregular trapezoid. The total length of the earthen entrenchment, measuring in a direct line from Ashley Bastion to Colleton Bastion to Carteret Bastion to Craven Bastion, extended to approximately 4,000 feet. If we add to this figure the additional distance created by the projecting, angular lines of the several redans, bastions, and ravelin, the precise dimensions of which can only estimate, we can calculate conservatively that the total length of the fortification ditch or moat around the town was approximately 4,500 linear feet.

Estimating that the ditch or moat was six feet deep and was between twenty-four and thirty-six feet wide at the top, with sloping faces on each side, we can calculate that the enslaved laborers working on this project in 1704 excavated between 450,000 and 800,000 cubic feet of earth. The height, breadth, and shape of the fortification wall constructed from that volume of earth is a complicated puzzle that we’ll unpick in a future program. In the meantime, I’ll simply note that the front face of the earthen walls erected in 1704, reinforced by wooden revetments, stood approximately eight to ten feet above the surface of the ground and extended a total or sixteen to twenty feet from the bottom of the sloping front face to the bottom of the sloping rear face.

Estimating that the ditch or moat was six feet deep and was between twenty-four and thirty-six feet wide at the top, with sloping faces on each side, we can calculate that the enslaved laborers working on this project in 1704 excavated between 450,000 and 800,000 cubic feet of earth. The height, breadth, and shape of the fortification wall constructed from that volume of earth is a complicated puzzle that we’ll unpick in a future program. In the meantime, I’ll simply note that the front face of the earthen walls erected in 1704, reinforced by wooden revetments, stood approximately eight to ten feet above the surface of the ground and extended a total or sixteen to twenty feet from the bottom of the sloping front face to the bottom of the sloping rear face.

To perform the work of excavating the ditch and shaping the earthen wall and wooden revetments, William Rhett and a handful of White overseers probably managed a daily crew of twenty to sixty enslaved laborers drawn from the town’s urban population who worked on a rotating schedule. This labor force probably completed the bulk of excavation work during the first half of 1704, and saved the completion of the finishing touches for the ensuing winter months.

The people of Charleston tolerated and maintained these entrenchments for a decade before they suffered significant damage during a pair of hurricanes in 1713 and 1714. Their efforts to repair the earthen enceinte were derailed by a series of distractions, including the Yemasee War of 1715–17, the pirate troubles of 1718, and the Revolution of 1719. The provincial legislature voted to remove the wooden revetments supporting the earthen walls in the spring of 1723; during the ensuing decade, the once stout walls slowly sloughed into the adjacent moat and gradually faded from the landscape.

If you haven’t already done so, the Charleston Time Machine and the Mayor’s Walled City Task Force invite you to perambulate along the path of the Charleston enceinte of 1704 on the city’s modern streetscape. Using today’s program as your guide, augmented by a healthy imagination, I hope you’ll appreciate this familiar landscape with a new sense of wonder.

[1] John Herbert’s manuscript plat is found at the National Archive (Kew), CO 700/Carolina6. This document, which measures approximately eighteen by twenty-four inches, contains a number of hand-written notes. An inscription at the top left corner reads “The Ichnography or Plann of the Fortifications of Charlestown, and the Streets, with the names of the Bastions[;] quantity of acres of Land, number of Gunns[,] and weight of their Shott, By his Excellencys Faithfull & Obedient Servt. John Herbert. Octobr: 27 1721.” In the lower right corner is a small scale with the following inscription: “A scale of Ten Chaines 66 Feete [sic] in a Chaine [sic] and two Ch: in an Inch.”

[2] The Ichnography of Charles Town. At High Water, published in London in 1739 by Bishop Roberts and W. H. Toms, includes a note that had misinformed many generations of historians: “The Double Lines represent the Enceinte as fortified by the Inhabitants for their defence against the French Spaniards & Indians without it were only a few Houses & these not thought safe till after the signal Defeat of ye Indians in the Year 1717, at which time the North West & South sides were dismantled & demolished to enlarge the Town.” Contemporary records of South Carolina’s provincial government demonstrate that the lines of the enceinte were maintained, to some degree, until the spring of 1723, when official neglect formally commenced. As late as 1732, however, the local government was protecting the earthen lines of the former fortifications around the town. This topic will form the focus of a future program.

[3] The earliest-known use of the bastion names appears in South Carolina Department of Archives and History (hereafter SCDAH), Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, Mr. Green’s copy, 1706–11, page 392 (13 December 1708).

[4] A brief illustrated description of the brick wall in the driveway of No. 43 East Bay Street appears in Nicholas Butler, Eric Poplin, Katherine Pemberton, and Martha Zierden. Archaeology at South Adger’s Wharf: A Study of the Redan at Tradd Street. Archaeological Contributions 45. (Charleston, S.C.: Charleston Museum, 2012), 127.

[5] The angle of 22.5 degrees at this transitional intersection is depicted in a 1755 plat of the said brick wall and palisades, which is annexed to a deed of feoffment from Adam Daniel to George Sommers, 4 September 1755, recorded in Charleston County Register of Deeds, VV: 668–69.

[6] See section IV and VI of Act No. 230, “An Act to prevent the breaking down and defacing the Fortifications in Charles Town,” ratified on 4 November 1704, in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 7 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1840), 36–37. Unless otherwise indicated, I have retained the original spelling found in the primary sources cited in this essay.

[7] See “An Account of what Guns are in the fortifications about Charlestown; also what are wanting, and of what size,” in SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, Mr. Green’s transcription, 1702–6, p. 256 (9 October 1704). This and subsequent references in this essay to the number of cannon in the town are drawn from this source.

[8] Professor Jon Marcoux of Clemson University has rendered invaluable assistance to the Mayor’s Walled City Task force since 2016, and my conclusions concerning the southern line of the 1704 entrenchment is indebted to his GPR work in the parking lot of First Baptist Church and adjacent private properties.

[9] Several surveys made during the 1730s, during the removal of the remnants of the 1704 entrenchments, confirm that the intended with of Meeting Street (“Old Church Street”) was sixty-six feet. See SCDAH, Surveyor’s Notebook for Charleston, pages 10, 11, 71, 72.

[10] Although the Herbert plat of 1721 places this redan slightly south of the intersection of Queen and Meeting Street, the placement of Dock (Queen) Street in Herbert’s map differs from the present alignment of that street. As described in the journals of the Commons House of Assembly and the Surveyor’s Notebook for Charleston, the general trajectory of Dock Street, between East Bay and King Streets, was altered during the period 1733–35, at which time it was renamed Queen Street. The alignment of this street and redan is depicted more accurately, therefore, in the 1739 Ichnography of Charles Town.

[11] For a description of recent efforts to determine the site of Carteret Bastion, see Butler, et al., Archaeology at South Adger’s Wharf, 131–32.

[12] At least three copies of the 1750 plat in question survive; two appear on pages 49 and 62 of the City Engineer’s Plat Book, Charleston Archive, Charleston County Public Library; a third copy is cataloged as item 32/15/04 at the South Carolina Historical Society.

[13] See section IX of Act No. 327, “An Additional Act to an Additional Act to an Act entitled an Act for repairing and Expeditious finishing of the Fortifications of Charles Town, and Johnson’s Fort, and for putting the said Fortifications in Repair and good order, and Sustaining the Same; and for Building a Publick Magazin [sic] in Charles Town, and for appointing a Powder Receiver and Gunner,” ratified on 7 June 1712, in SCDAH, Nicholas Trott’s manuscript “New Collection” of the Statutes of South Carolina, Part II, pp. 47–51.

[14] For more information about the efforts to build a brick “wharf wall” on the east side of East Bay Street between 1694 and 1702, see Episode No. 180, Episode No. 181, Episode No. 197, and Episode No. 210.

[15] See Section XI of the 1703 act described in Episode No. 221.

[16] SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, Mr. Green’s transcription, 1702–6, pp. 249–50 (5 October 1704).

[17] Act No. 230, “An Act to prevent the breaking down and defacing the Fortifications in Charles Town,” ratified on 4 November 1704, in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 7 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1840), 36–37. Several parts of this act were extended in 1746 by Act No. 740.

[18] Act No. 231, “An Act against the Killing of Beasts within the Intrenchments of Charles Town,” ratified on 4 November 1704, in McCord, Statutes at Large, 7: 38.

[19] SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, Mr. Green’s transcription, 1702–6, pp. 296–97 (6 November 1704).

[20] SCDAH, Journal of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly, Mr. Green’s transcription, 1702–6, p. 296 (6 November 1704). Governor Johnson approved this order later the same day.

NEXT: Where Did Robert Smalls Live in 1862 Charleston?

PREVIOUSLY: Swords, Fencing, and Masculine Choreography in Early Charleston

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments